Johnny Cash’s profile, framed with his tousle of black hair and sideburns, is as familiar as the many songs for which he is fondly remembered. In his deep voice, Cash sang traditional ballads, spirituals, gospel, bluegrass, country, blues, folk, rockabilly, rock ’n’ roll, and rock. Revered throughout the world, he needs no introduction. No other musician mastered such a range of styles, and his sales of more than 90 million records attest to their popularity.

Cash’s all-black wardrobe earned him the nickname the “Man in Black,” and he opened each concert with his familiar line, “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash.” He was part of the “Million Dollar Quartet” that Sam Phillips recorded at Sun Records in Memphis in 1956, along with Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Elvis Presley. Cash broadened his own musical roots in the Deep South when he married June Carter, whose family are considered the aristocracy of country music in the Upland South.

Cash’s roots were humble. He grew up on government-granted land in the Arkansas Delta, and that hardscrabble world of poor farmers helped define his musical career. During his early years as a musician, he performed for small audiences like the Merigold High School junior class in Merigold, Mississippi, a Delta town with a population of 664. In 1955, the class planned a fund-raiser to support their trip to Washington and invited Elvis Presley to perform at the event. Their classmate Larry Speakes—who later served as White House press secretary during the Ronald Reagan administration—and his band had recently played on the same stage with Elvis at Ellis Auditorium in Memphis, where he met Bob Neal, Presley’s manager at the time. Speakes phoned Neal, who told him that Presley’s fee to do the show would be $85, which Speakes said they could not afford. Neal then offered to send both Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins for $35, and Speakes readily accepted.

The legendary concert was in the school gymnasium, which was built by the New Deal Works Progress Administration in 1938. It drew a sellout audience of 400, and tickets sold for 60 cents each. Fish Michie, a Merigold native and former keyboard player with the Delta band the Tangents, memorialized the concert in his 2020 article in Delta magazine, “Rockabilly in Merigold: Elvis Didn’t Work Out, So Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins Rocked Bolivar County,” illustrated with a promotional photograph Cash signed for Eunice Howell, a student in the junior class: “To Eunice, Best Wishes, Johnny Cash.”

Eunice’s classmate Gwen Daves recalled the concert; it was still fresh in her memory when I spoke with her earlier this year. “I was fifteen then. I am eighty-two now. We were in an auditorium, and when Johnny Cash sang, he was wonderful. We got so excited that we stood up on the chairs. We were crazy about him.”

I discovered Johnny Cash as a teenager in Vicksburg, Mississippi, when Sam Phillips released his song “I Walk the Line” on Sun Records in 1956, and it sold more than two million copies. Cash etched his lyrics into the memory of our generation as he sang:

I keep a close watch on this heart of mine

I keep my eyes wide open all the time

I keep the ends out for the tie that binds

Because you’re mine, I walk the line.

We played rock ’n’ roll and rhythm and blues records at our dances, and Cash’s “boom-chica-boom” rhythm on “I Walk the Line” fit in nicely with the music of Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Jerry Lee Lewis. In the decades that followed, Cash’s impact reached far beyond teenage dances, as he wrote two autobiographies Man in Black and Cash: The Autobiography, hosted The Johnny Cash Show on television, and was the subject of the Hollywood film Walk the Line. He also inspired performers as diverse as Bob Dylan and Marty Stuart. Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash were friends for more than 40 years. After Cash’s death, Dylan movingly described his friend:

In plain terms, Johnny was and is the North Star; you could guide your ship by him—the greatest of the greats then and now. . . . If we want to know what it means to be mortal, we need to look no further than the Man in Black. Blessed with a profound imagination, he used the gift to express all the various lost causes of the human soul.

The first country music album Marty Stuart owned was The Fabulous Johnny Cash. He played in Cash’s band from 1980 to 1985 and he was married to his daughter Cindy from 1983 to 1988. Stuart recalled to Whiskey Riff country music website how he took the last photographs of Cash just before his death in 2003:

He was sitting there in the light. The afternoon light from the lake was touching him on his back.

I said, “JR, let me take your picture.” He said, “Ok.”

I shot three frames. In the first two he looked like a little old man. I said, “JR!” and he sat up straight and he pulled that collar. And he became John R. Cash, and I got the picture.

LeRhonda Manigault-Bryant, who directs the University of North Carolina’s Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History, told me that as a child in Moncks Corner, South Carolina,

the music of Johnny Cash frequently billowed out around our home—literally a five-room shack—because of my grandfather, Sanford Brown (1929–2003), who survived the Korean War as a U.S. Army veteran. Grandaddy was a man of few words. He always had a fifth of whiskey nearby, but as much as he enjoyed a sip of whiskey, country music was his true salve. It was always on at the house, so much so that country music, like gospel music, became my first love.

I am convinced that although my grandfather left our family church long before I was born, he stayed connected to God through Johnny Cash. The Man in Black turned country music into spiritual lament, contemplative dirge, or raucous shout song, and sometimes all rolled into one. Johnny Cash mastered the art of musical connection—his music would call to you and speak to something indescribably deep within.

As we consider Cash’s career and the range of musical worlds it embraces, our challenge is to understand its breadth as well as its enduring themes of social justice and the human condition. And to do that we must understand Cash’s childhood in Dyess, Arkansas, a story captured by the Heritage Sites Program at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro.

Under the leadership of the program’s founder, Ruth Hawkins, and its executive director, Adam Long, faculty and students have preserved and interpreted historical sites in the Arkansas Delta that include the Dyess Colony buildings in Dyess, the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum in Tyronza, and the Lakeport Plantation house in Lake Village. These sites offer a powerful historical backdrop for understanding Cash’s music and his commitment to working-class people. They demonstrate how a humanities partnership between Arkansas State University and the Arkansas Delta have transformed a region known for its rural poverty into a destination that offers educational and cultural opportunities for students and travelers from throughout the world.

Lakeport Plantation and its plantation house were built by enslaved labor who cut virgin forests and created a 4,013-acre cotton plantation that was owned by the family of Joel, and later Lycurgus, Johnson from the 1830s to 1927, when it was sold to the Epstein-Angel family, descendants of eastern European Jewish immigrants to the Arkansas Delta. The Sam Angel family of Lake Village gave the plantation house to Arkansas State University in 2001. The Southern Tenant Farmers Museum is the former headquarters of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, which was organized by two Tyronza businessmen, H. L. Mitchell and Clay East, who also founded the Socialist party in Arkansas. In response to the eviction of sharecropper families from local plantations, Mitchell and East organized the union in 1934 with seven Black members and eleven white members. It was the first agricultural union to include both Black and white farmers and to place women in leadership positions.

The Dyess Colony was created in 1934, as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, as a way to support the “independent farmer.” Following the Mississippi River Flood of 1927 and the stock market crash of 1929, two-thirds of Arkansas farmers lost their land and became tenant farmers. To give these farmers a second chance, Roosevelt purchased 16,000 acres of bottomland swamp in Mississippi County, Arkansas, and developed it as a “resettlement community.”

Dyess Colony houses, its community center, and its modernized Georgian style administration building were designed by Howard Eichenbaum, a Jewish architect in Little Rock. Inspired by houses in small southern towns, Eichenbaum designed 20 variations of small three- to five-room homes wired for electricity with low-pitched roofs, wood siding, front and back porches, and a well.

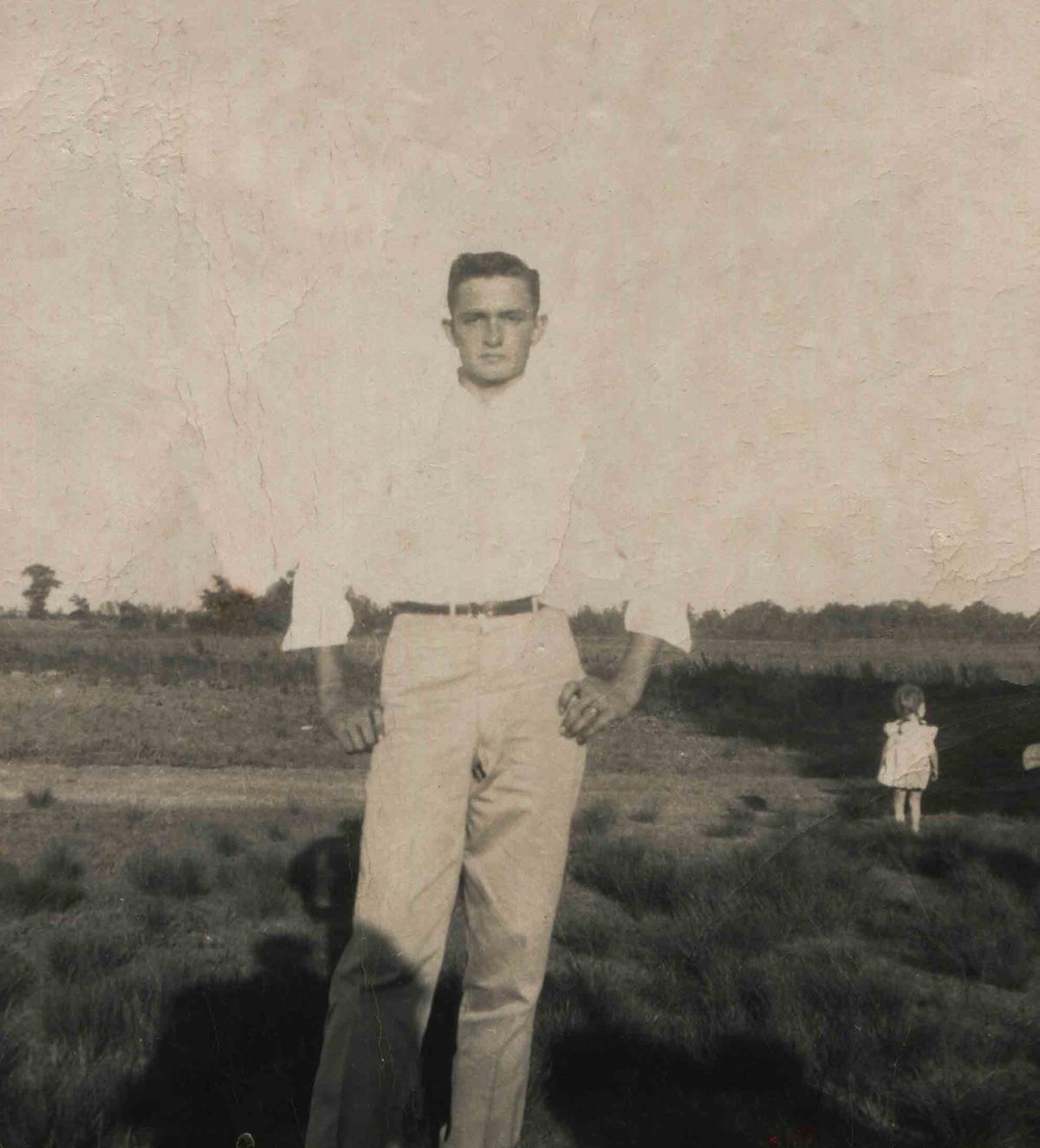

Five hundred white families were given farms of 20 to 40 acres that included a house, barn, privy, a mule, a cow, chicken coop, and food and supplies to support the family until they harvested their first crop. Each family cleared the land and cultivated their crops on it. In the winter of 1935, Ray and Carrie Rivers Cash moved into one of the homes with their children, one of whom was three-year-old Johnny Cash.

Food scholar—and my wife and partner—Marcie Cohen Ferris describes life in the Dyess Colony:

The typical meals of low-income northeastern Arkansas families of this era included beans and peas seasoned with ham hock, pots of greens, sautéed cabbage, poke sallet or wild greens, and seasonal vegetables from the garden patch. Rice was topped with a tomato ‘gravy’ and stews were served with biscuits and cornbread. Locals ate fried fish, wild game such as deer, turkey, squirrel, rabbit, duck and quail, and side dishes of pickled cucumbers and onions, coleslaw, and potato salad. Those who could, raised and slaughtered a hog, using some of the fresh meat, and preserving other cuts for later in the year. When First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited Dyess in June 1936 and drove through the region, she would have seen small food-related businesses, including Black- and white-owned barbecue cafes and hot tamale stands, and grocery stores, cafes, and restaurants owned by Greek, Asian, Lebanese, Syrian, and Jewish Arkansans.

Cash graduated from Dyess High School in 1950 as the vice president of his class. He later recalled his family’s poverty and their dependence on the cotton crop for survival in the Dyess Colony in his song “Pickin’ Time”:

I got cotton in the bottom land

It’s up and growing and I got a good stand

My good wife and them kids of mine

Gonna get new shoes, come Picking Time

Get new shoes come Picking Time

Even the best farmer could lose his crop if the Mississippi River flooded his fields, as is the case in Cash’s “Five Feet High and Rising”:

How high’s the water, mama?

She said it’s two feet high and risin’

How high’s the water, papa?

Two feet high and risin’.

Well, we can make it to the road

in a homemade boat

That’s the only thing we got left that’ll

float

It’s already over all the wheat and oats

Two feet high and risin’.

Other songs like “The Man on the Hill” referred to racist and classist plantation economies and the power of white landowners over sharecroppers, as a son asks his father:

Will we get cold and hungry

Will times be very bad?

When we are needing bread and meat

Where are we going to get it, Dad?

We’ll get it from the man

In the house on the hill

Yes we will from the man on the hill.

Cash was keenly aware of the plight of poor Black and white families, and his concern for those families is captured in the albums of concerts he recorded in prisons, the most famous of which, Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, reached number one on the country charts. Cash’s personal identity with the poor permeates his musical career and was inspired by his childhood experience in Dyess. It is also framed by the plantation system in the nineteenth century and by Black and white tenant farmers who struggled against exploitation by landowners in the twentieth century. This history is captured and interpreted in Arkansas State University’s Heritage Sites at the Lakeport Plantation house, the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum, and the Dyess Colony buildings. These sites offer a deep history of both the American South and the Arkansas Delta, a history that is animated by the life and music of Johnny Cash.

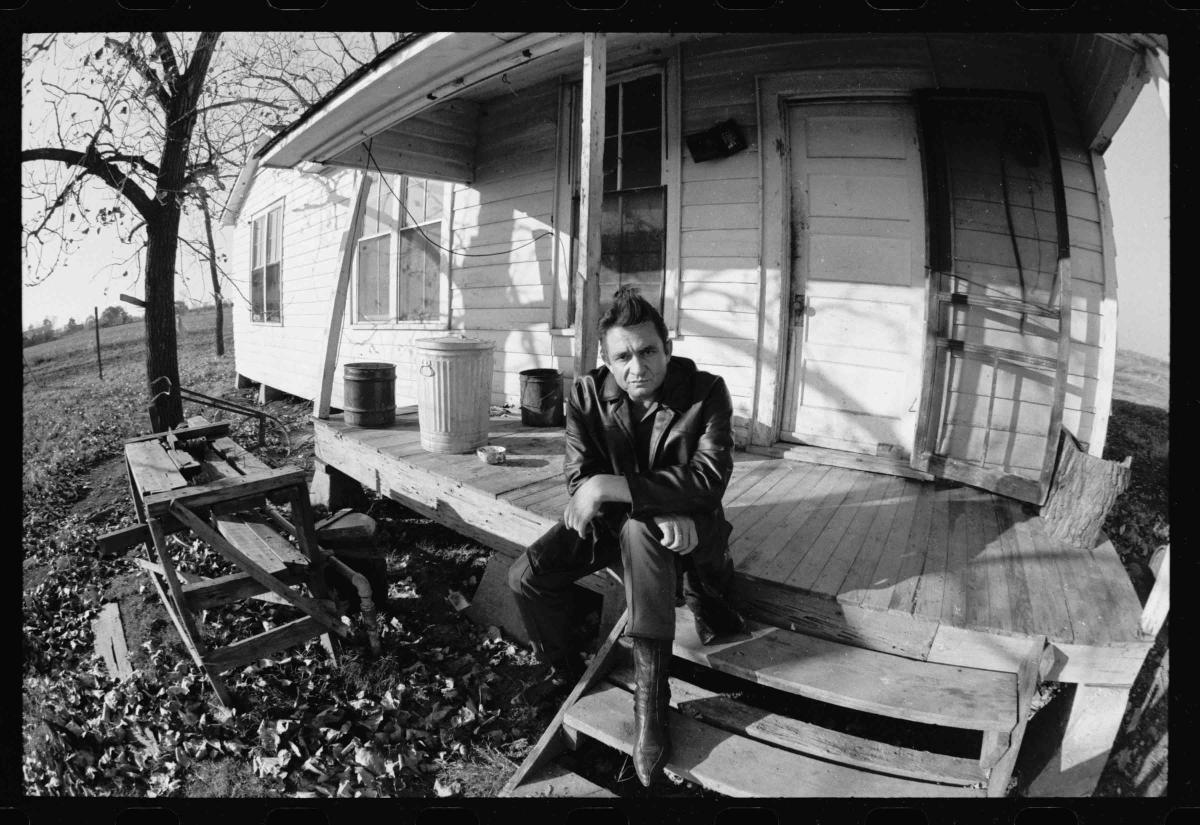

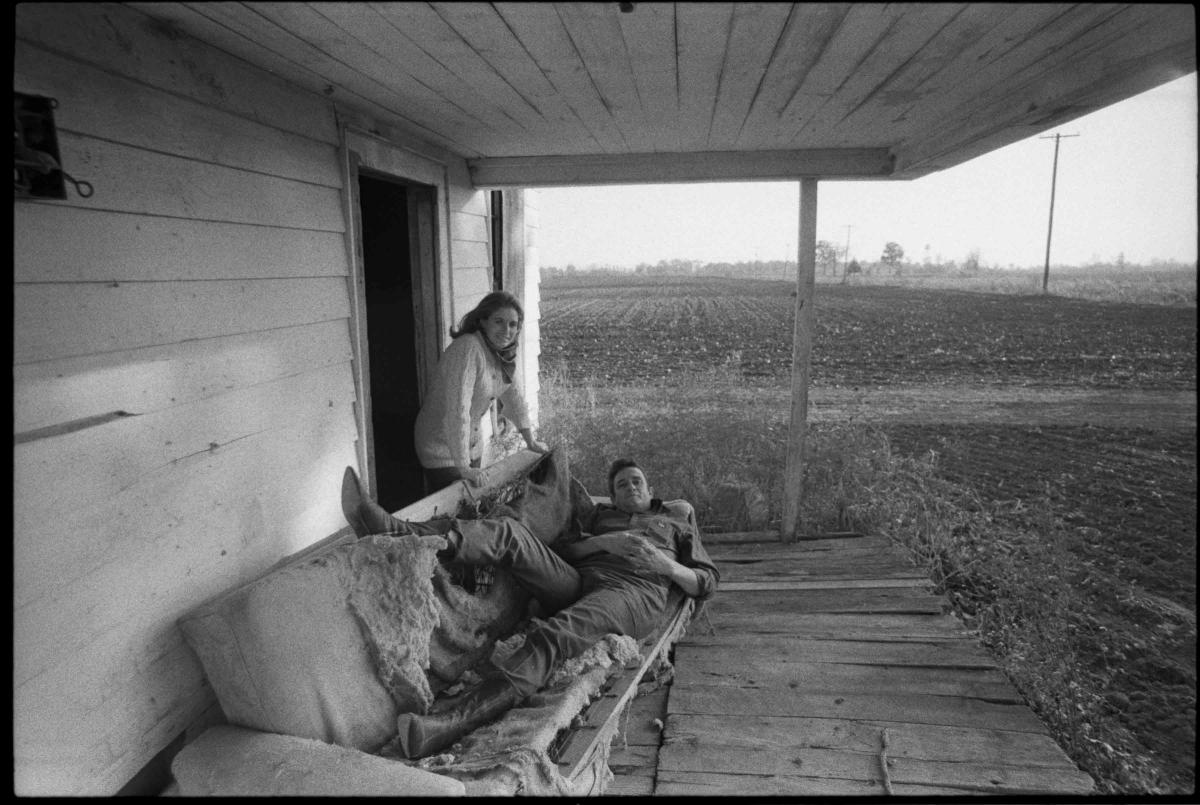

The Johnny Cash home, like the childhood homes of Elvis Presley in Tupelo, Mississippi, and of Muddy Waters in Clarksdale, Mississippi, are preserved as monuments to artists whose careers transformed twentieth-century music for our nation and the world. Cash’s childhood home, a five-room Dyess Colony farmhouse, stands beside a gravel road in the middle of a large cotton field one mile from the Colony center, where the school, store, and other community amenities like a movie theater were. It is now a destination for thousands of musical pilgrims who travel from throughout the world each year to pay tribute to Cash and his music.

Just as William Faulkner’s home Rowan Oak is owned by the University of Mississippi, which hosts an annual Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference in Oxford, Mississippi, the Cash home is owned by Arkansas State University, which hosts an annual Johnny Cash Heritage Festival in Dyess. The festival features scholarly lectures, films, and has hosted performers like Rosanne Cash and other members of the Cash family, Marty Stuart, and Kris Kristofferson.

Both the preservation of the Cash home and the festival were the dream of Ruth Hawkins, who ended her 41-year career at Arkansas State University in 2019. Inspired by the story of Johnny Cash, Hawkins crafted a partnership that transformed both her university and the Arkansas Delta, as she secured grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Park Service, Save America’s Treasures, and the State of Arkansas for more than 15 million dollars to support preservation projects in the Arkansas Delta.

To integrate these sites into the university’s academic program, Hawkins created a Heritage Sites Program that awards doctorates to students whose research focuses on historical sites in the region. Hawkins recruited Clyde Milner as director of the program. A distinguished historian who did his doctorate in western history at Yale under Howard Lamar, Milner used the heritage sites as a laboratory for research by faculty colleagues and their students. His students included Minnijean Brown-Trickey, one of the Little Rock Nine who integrated Central High School in 1957.

Hawkins recalled how, when she first saw the Cash home, it was “in terrible condition. Its foundation of concrete piers had fallen over, and the home had sunken in the middle.” To raise support for the home, she used a video clip from Johnny Cash’s Dyess High School reunion, where Cash says, “It’s vital for us to remember to keep our feet on the ground, regardless of where we are or what we’re doing, and to go back to the things we were taught and were brought up on.”

For Rosanne Cash, one of Johnny Cash’s daughters, her ancestral home summons a trove of memories. She recalls:

I was twelve years old when my father took me to see his childhood home in Dyess, Arkansas. The house was boarded up, dilapidated, with brush all around the outside. I thought it was sad.

It was like a spiritual circle when I went back after Arkansas State restored the house. It was a gift of spiritual restoration for me and my family.

Hard work and the memory of that hard life inspired my father’s songs. The house is a physical remnant of those memories. Only a handful of the original 500 homes remain, and ours was close to disappearing. The home is a gift to both past and future generations of my family.

My grandmother raised seven children in that home, and they all picked cotton in the fields outside. I hope I have her tenacity as a modern working mother in New York City. My father learned lessons from his hard work in cotton fields. He applied those lessons in his work ethic, and I try to do the same.

Today, the Dyess Colony is significantly reduced. From its 1936 high point of 2,500 residents, only 515 remained at the time of the 2000 census. Its significance as the home and inspiration for Johnny Cash’s iconic American music, however, is forever fixed in history. We can be grateful that Cash’s roots in the Arkansas Delta and his unparalleled musical career are preserved and interpreted in ways that touch the heart and broaden our understanding of the humanities.