When leather-clad singer Rob Halford of the heavy metal band Judas Priest toured the United States in 1978, he picked up a piece of subversive literature in San Francisco to steer him safely as he sought companionship on the road. The slim, tiny volume with a monochromatic cover bore the nondescript title Bob Damron’s Address Book. As Halford later divulged in his 2020 memoir, not even bandmates on his tour bus could guess that this Damron guidebook provided their front man with a coded treasure map to America’s gay underworld, from Texas truck stops to Detroit bookstores, as they shuttled from gig to gig.

Indeed, Halford, the famed “Metal God,” felt secure enough in the ruse to carry the booklet in his back jeans pocket. The words “gay” or “homosexual” didn’t appear in its pages; readers in the know were compelled to translate a bit of gay lingo to access its materials, which provided plausible deniability should the wrong sort of person go snooping. In the years when a closeted gay celebrity like Halford stood to lose his position in music if his sexuality became widely known, Damron, hailed as the “first name and last word” in gay travel, helped keep a secret life secret.

Similarly, but decades later, when the New York theater company Aquila went on a national tour of classic plays like Much Ado About Nothing, actor Louis Butelli counted on his Damron’s Address Book to find gay watering holes and combat loneliness. Butelli attested to the New York Times that it was a “life-saving device.” Both Halford and Butelli represented the guidebook’s traditional target reader: the discreet gay man seeking fellow travelers, as it were, in unfamiliar settings. For more than half a century, from 1965 to 2021, the annual Damron’s Address Book served as a mash-up between the gay Green Book and the gay yellow pages—a lightly cyphered compendium identifying queer havens in hundreds of American towns and cities.

This publication was the masterwork of a real American entrepreneur named Bob Damron, a mustachioed San Francisco bar owner who decided to put a personal stamp on a niche offering and became a name of legend. “Compiler Bob Damron . . . personally visited some 200 cities in 37 states and toured Canada to obtain data presented here,” explained the introductory notes to the 1965 guide. A savvy broker of information, in addition to being a savvy marketer according to oral historian Martin Meeker in the 2006 book Contacts Desired, Damron forged a countrywide network out of then-isolated gay cell communities through long-distance phone calls and letters as well as by personally stopping in.

“There is a big desire for gay people to support gay businesses,” avowed Damron, a veritable Johnny Appleseed who cavorted his way across social boundaries, to scholar Wayne Sage in the 1979 anthology Gay Men: The Sociology of Male Homosexuality. Damron’s real name became a national gay calling card at a time when pseudonyms and aliases (such as Daughters of Bilitis president Helen Jane “Sandy” Sandoz going by Helen Sanders) were commonly used by queer authors and activists to avoid becoming criminal targets. The foregrounding (some would say flaunting) of his true identity reinforced Damron’s image as a traveler with derring-do who Jack-be-nimbled his way out of discrimination and police harassment.

In an era without employment or housing protections for sexual and gender minorities, when most gay men risked losing jobs and homes if their legal names ever became associated with a “crime against nature” (as private same-sex acts were then categorized by states until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled such prohibitions unconstitutional in the twenty-first century), Damron leveraged societal conventions and business acumen to carve out a perch of gay privilege. Robert Eugene Damron was born in Los Angeles in 1928 to a conservative Mormon household, his mother a housewife from Utah and his father a salesman whose parents were early Mormon settlers of eastern Arizona. According to U.S. Census records, young Damron grew up at 1130 S. Ridgeley Drive, a modest middle-class home in L.A.’s Mid-Wilshire neighborhood. A public school kid, he sprouted early and towered in the back row of his John Burroughs Middle School class yearbook photo, which stated in the caption that he planned to be a diplomat when he grew up—in other words, a traveling attaché, a man abroad. By age eighteen, Damron stood a confident six feet one inch tall and a svelte 165 pounds, or so stated his World War II draft card. Gray-eyed and dark-haired, he caught the eye as a strapping young buck.

While attending Los Angeles High School, he lent his voice to a teen AM radio show called “Youth Interprets the News,” which received mention in the Los Angeles Times. After his parents divorced contentiously in the late 1940s, his father moved back to Arizona, where he served as a high priest within the L.D.S. Church. Young Damron stuck around after graduation to support his mother, who had married as a teen and could read and write but had no schooling or professional trade, through age fifty-five. Undoubtedly, his mother’s situation served as a lesson in dependency versus financial independence. (It’s significant that Damron’s father maintained his L.D.S. status despite the divorce, as it points to excommunication or disaffiliation factors for the ex-wife and children. Damron didn’t write or publicly speak about his Mormon upbringing, and he received only a brief mention in his father’s 1969 obituary.)

Damron tried his hand at community college. To no avail. And he somehow avoided Selective Service commitments to the Korean War, though he was of draft age and peak physical fitness and did not maintain a student deferment. Slowly discovering himself, Damron dived headlong into the bar industry as he explored his sexuality throughout his twenties—first owning and operating straight bars, then mixed bars, then “guy bars” (as gay bars were often called) in Los Angeles. A born socialite, the man’s appetite for casual conversation, as well as the casual encounter, was famously voracious. “My favorite indoor (and occasionally outdoor) sport . . . SEX!” Damron later jested in the Los Angeles gay newspaper The Voice. Jumping from bar to bar as a fractional owner and never quite staying put, Damron went on to own the (appropriately titled) Gaiety off S. Western Avenue as well as the Red Raven gentlemen’s club by the close of the Eisenhower years.

Damron transplanted to San Francisco’s Castro district in time for the acid craze and “free love” flourishing. As the city’s homosexual underground emerged streetside, he opened a gay bar ironically called the Hideaway on Market Street. On the scene in San Francisco, he crossed paths with Mattachine Society president Hal Call. “Bob Damron was smarter than I was,” said Call to historian James Sears in an oral history interview for the 2006 book Behind the Mask of the Mattachine. The Mattachine Society was an early gay rights organization that sought to decriminalize homosexuality by portraying gay men and women as responsible taxpayers and employable citizens. “When will the homosexual ever realize that social reform, to be effective, must be preceded by personal reform?” asked a writer in a 1956 issue of the Mattachine Review, a monthly newsletter for the group’s “homophile” (derived from the Greek words homo and phile, meaning “same love”) readership that Call edited.

A multifaceted man of business, over and above his Mattachine crusades, San Franciscan Hal Call operated a gay press called Pan-Graphic and a national gay book distribution service called Dorian. At a time when homosexual literature often ran afoul of state and federal obscenity laws, Pan-Graphic printed the Mattachine Review as well as assorted gay literary fiction. Quite literally buying into gay culture as investors, Damron and Call stood among a generation of post-World War II gay entrepreneurs who gained a foothold in their communities as business proprietors. Previously, organized crime syndicates had largely dominated non-hetero spaces and services. “Ten years ago maybe 25 to 30 percent of the [gay] bars in San Francisco were gay owned,” Damron told scholar Wayne Sage. “Today, they’re probably 75 to 80 percent gay owned.”

Although other gay compendiums, such as The Lavender Baedeker, preceded its publication, the original Address Book represented perhaps the first such work to emerge directly out of the homophile movement’s platform of gay agency. “I made up a mimeographed list of bars in 1955 when we had our annual Mattachine meeting,” Call recollected to James Sears. “It had thirty-five gay bars. We had people sign for it because we didn’t want it to fall into the hands of police. I put a number on each copy.” In 1964, Call and Damron decided to collaborate to create a more formalized and expansive accounting of the national gay circuit. Damron hopped into his car and went from coast to coast with an open notebook. Afterward, Call edited and typeset Damron’s scribblings onto thin, bible stock paper through the Pan-Graphic Press. Expecting a small readership, they printed a mere 3,000 copies of the first edition, which cataloged 785 locations across nearly 50 pages, according to the online database Mapping the Gay Guides (an NEH-sponsored digitization project of the Address Books from 1965 to 1989). Damron kept the exclusive copyright to the work.

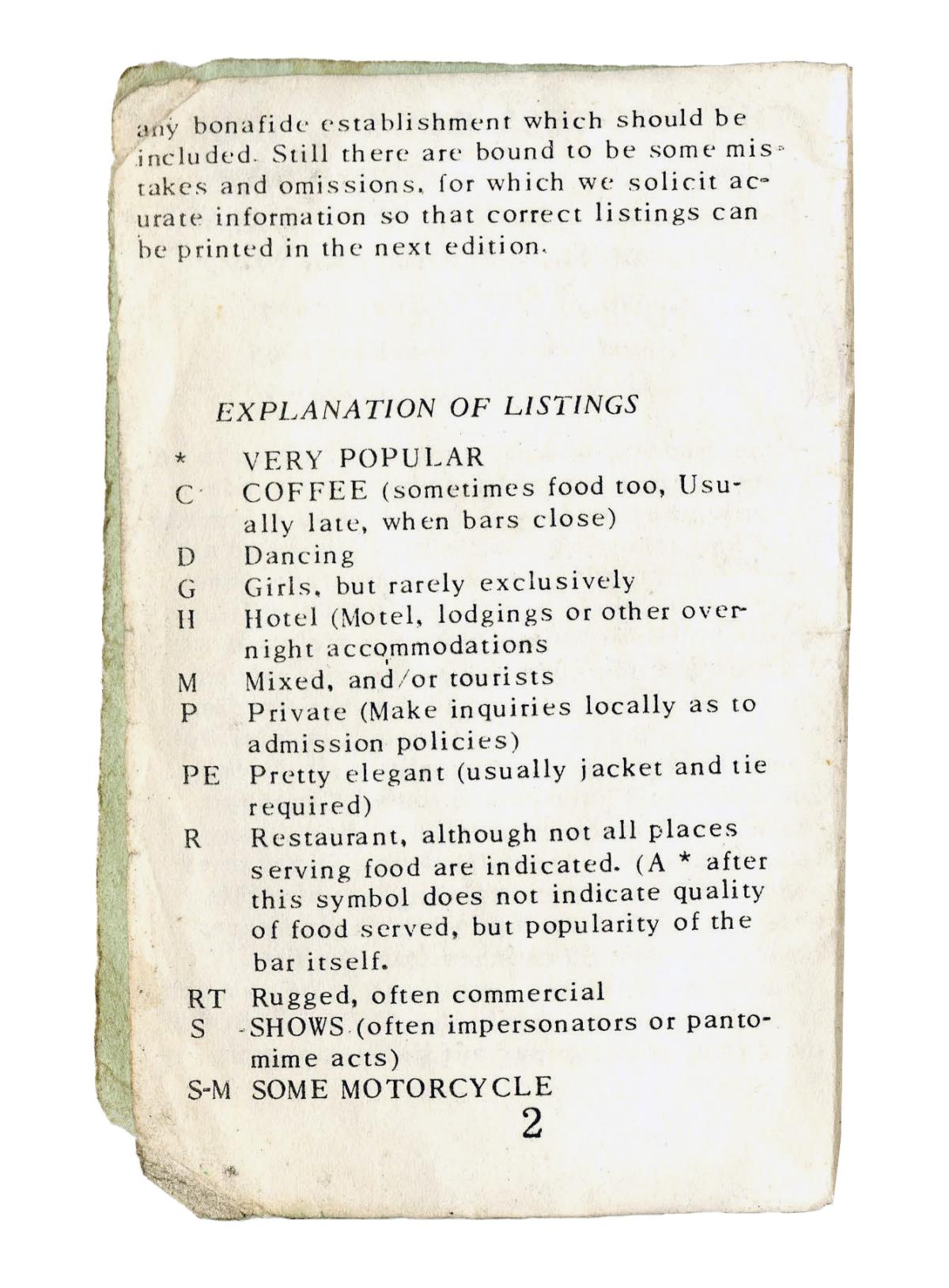

As sodomy remained illegal in all states but Illinois, author and editor shrewdly chose to present their contents, which encouraged the perpetration of sex crimes, in a visually tame manner. Each citation in their booklet included just a bar name, an address, and maybe one coded letter or symbol. Their sly “Explanation of Listings” was engineered to mislead straights, with labels ranging from “C” (defined as “Coffee,” but likely meaning cruising grounds) to “RT” (defined as “Rugged,” or “Raunchy Types,” but likely meaning rough trade) to “S-M” (defined as “Some Motorcycle,” but likely meaning sadomasochism). Listings encompassed the rural and the urban, blue- as well as white-collar tastes, ranging from “Mr. B’s*” (the asterisk signifying “Very Popular”) in Calumet City, Illinois, to New York City’s Everard Baths to the “Silver Dollar (S-M)” in Jackson, Wyoming. The last few pages were dedicated to Canada.

As this was a document drafted on the know-how of a hirsute white pleasure-seeker amid widespread misogyny and gay racial segregation, it should be no surprise that few “G” (Defined as “Girls,” but meaning lesbian) bars appeared in the first Address Book editions. Likewise, no “B” (“Blacks Frequent”) bars would be included until 1970, although Black gay spaces existed widely. Inclusivity concerns seemed a step beyond Damron’s enthusiasms.

Nonetheless, when the Address Book first hit newsstands in 1965 at a cost of $3 per copy, readers gained access to one of the most complete censuses to date of an illegal subculture in hiding. Leveraging his publishing enterprises synergistically, Call advertised the 1965 Address Book through the Mattachine Review and distributed it via mail through his Dorian Book Service. Damron contacted bars featured in the guide and got owners and managers to commit to buying multiple copies, which made them customers and vendors of the product. “They were sold all over and caught on very fast,” said Call. Pioneers who frequently put their creased, thumbed-through guides to the test were known to personalize their pages by making additional notes about locations in pencil. “One of the things I found when using them from personal experience, they were generally a year out of date and some of the places might have changed,” recalled Bud Thomas, manager of ONE Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries, in a recent interview. “It was a good starting point to, like, hit place A, B, or C. You’d find one place that was definitely a queer bar, and then you’d find whatever the gay local rag was on top of the cigarette machine, and then you’d find out the truth.”

By 1966, Damron and Call were feverishly printing a midyear edition with updates to meet demand. In March 1967, the two partnered separately to open a bookshop on Ellis Street called Adonis; with more than 800 queer titles, including the Address Book, the Adonis represented one of the first gay bookstores in the United States, as more fully explored in the book Buying Gay by David Johnson. Damron’s role with the guidebook, given his wanderlust, proved to be ever expanding. By 1968, he officially tied the publication to himself by branding it Bob Damron’s Address Book—the act both a status symbol and a source of aspiration for gay men who dreamed of someday living “out” to the same degree. The booklet blossomed in size until it eclipsed more than a hundred pages, which proved too much for Pan-Graphic Press to handle. So Damron spun off the travel book business into yet another one of his legal entities: Calafran Enterprises, an erotic publishing company that had heretofore specialized in magazines with full frontal male imagery. After 1968, only Damron-owned subsidiaries would print and distribute his namesake. “I should have owned half of it, but I didn’t—to my regret,” rued Call.

All the while, Damron kept a foothold firmly in the San Francisco gay-bar scene. He hopscotched as owner of the Hideaway to Rendezvous to the reservation-only gay restaurant and piano bar P.S. “I didn’t know Bob Damron and Bob Trollop EVER went to the tubs!” teased a Bay Area Reporter columnist who spotted Damron out at the local bathhouse with a fellow restaurateur. Damron’s last major bar opening was the San Francisco Eagle in 1981. A near-instant hit with the gay leather crowd, the Eagle raked in “an estimated gross of 1.5 million dollars” in its second year alone, according to Bay Area Reporter journalist Karl Stewart.

By the Reagan era, the Address Book catered to an increasingly segmented set of gay archetypes and subcultures. New terminology such as (W) “Western or Cowboy Types” appeared in the “Explanation of Listings” legend. The booklet also began offering a handkerchief color code guide for gays out cruising with specific tastes. A green handkerchief positioned in the left back pocket, for example, would indicate “Hustler.” In 1980, Damron launched a syndicated human-interest column in gay newspapers and magazines called “Doing America with Bob Damron.” The tone was breezy. “On most late nights, there are more horny guys upright . . . than there are palm trees,” joked Damron in his review of Palm Springs, California, for The Voice.

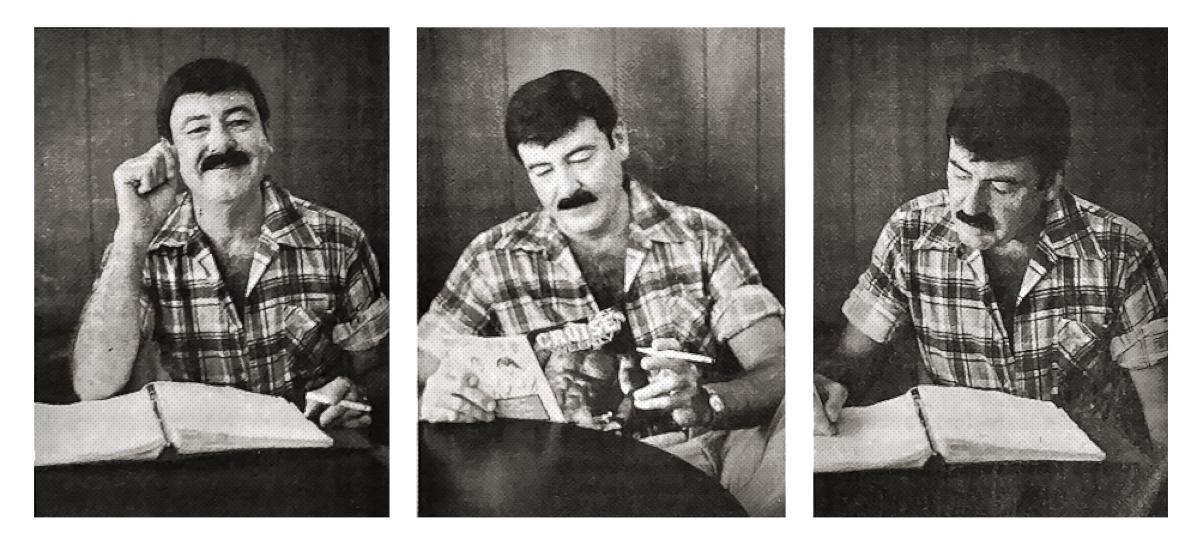

In the pages of Buffalo, New York’s, Mattachine newspaper, Fifth Freedom, Damron recommended Monterey Bay as a weekend getaway, though it might not be as gay-centric as Key West. “It is nonetheless a wonderful place to vacation,” he wrote. “If possible, take along a friend or lover, but if not, chances are you’ll be able to score someplace along the way.” With a self-promotional headshot often appended to each story, plus a requisite callout to buy the latest Address Book, Damron achieved the closest thing yet to gay ubiquity. The man embodied a brand, like gay Pepsi. Randoms could pick him out of a crowd. “What do you do in a city that Bob Damron hasn’t been to yet?” asked a Bay Area Reporter columnist rhetorically in 1982.

It’s unknown when Bob Damron received the diagnosis that stopped him cold, but when he abruptly sold Bob Damron Enterprises to Dan Delbex in 1985, the business was booming. Nearly a hundred thousand copies of his guide circulated annually, estimated Mapping the Gay Guides, and he was only fifty-seven, a little early for a vigorous man to cash it in. “After witnessing Intl. Mr. Leather in Chicago last May, tis rumored Bob Damron will be throwing a huge Mr. Gay USA pageant here [in San Francisco],” speculated the Bay Area Reporter, clearly not in the loop that July. This would be virtually the last mention of the gay mogul out and about in the so-called Gay Mecca’s newspaper of record. Soon afterward, Damron sold his stake in the beloved San Francisco Eagle bar.

Damron moved back to Los Angeles to live with his older brother Norrie, who became his caretaker. He told friends that he planned to spend his retirement writing historical biographies. Robert “Bob” Eugene Damron, geographer of several gay generations, died of AIDS complications on June 20, 1989. His family held a funeral on June 28 in Los Angeles, and his ashes were promptly scattered at sea. Friends in leather subsequently hosted a larger “celebration of life” service at the San Francisco Eagle, which is now a designated cultural landmark on 12th Street following 40-plus years serving the community.

After Judas Priest front man Rob Halford declared his homosexuality on MTV News in 1998, the “Metal God” published a tell-all memoir entitled Confess, in which he credited Damron with shepherding him through America’s gay hunting grounds. “It felt like it was the best option I had open to me,” Halford wrote of his furtive lifestyle. “In fact, it was the only option.” The annual Damron guidebook persisted into the twenty-first century, when queer decriminalization set the stage for gay men to finally appear on its cover. By then, many of the code words and subculture phrases had outlived their original meanings, including the word “queer.” With more than twelve thousand travel listings at final printing, Damron marshalled a global gay citizenry until it surrendered to Google Maps and hookup apps and went the way of all things that glitter discreetly.