In the 2018 movie Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Melissa McCarthy played Lee Israel, a real-life writer who made ends meet by creating and selling fake correspondence attributed to literary celebrities.

Initially, Israel thrives at simulating the voices of various persons of letters, but she’s eventually undone after her fanciful version of a Dorothy Parker letter doesn’t add up. A subtle suggestion of Can You Ever Forgive Me?, which takes its title from an apology for drunkenness Israel fictionalized for Parker, is that the celebrated author just can’t be imitated successfully.

True, perhaps, though that observation might not resonate among those viewers who aren’t familiar with Parker’s work. The film makes no effort to explain who Parker was, apparently assuming that her popular profile endures.

But we don’t hear much about Dorothy Parker these days, although her sardonic poems, essays, and short stories remain reliably in print. Half a century after her death, she’s remembered—to the degree she’s widely remembered at all—as a belle of the bon mot, the razor-tongued epigrammatist who held court with other intellectual gadflies of the 1920s at the Algonquin Round Table.

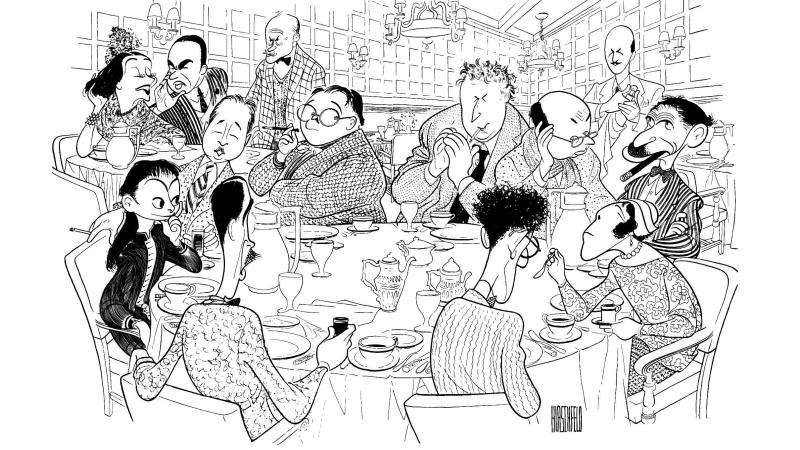

That informal assemblage of lunchtime literati at Manhattan’s Algonquin Hotel, which also included Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, and George S. Kaufman, was a fixture of the Jazz Age. But the Round Table’s legacy seems to abide today mostly as a quaint period piece, a phenomenon that defined its era without quite transcending it.

The Round Table inspired at least one admiring observer to place the Algonquin’s Rose Room, the seat of the gatherings, within the grand intellectual tradition of the eighteenth-century London coffeehouse. It’s a comparison that doesn’t seem to hold up very well with the passage of years. As Leo Damrosch recently reminded readers in The Club, his account of legendary lexicographer and polymath Samuel Johnson’s social circle, the convivial culture of 1700s London cultivated not only Johnson, but classical economist Adam Smith, seminal historian Edward Gibbon, and groundbreaking biographer James Boswell.

The Round Table, on the other hand, gave a forum to Benchley, a humorist little read today, and Woollcott, who’s now equally obscure. Kaufman has a place in posterity as the man behind some Marx Brothers musicals and Guys and Dolls, but whether this qualifies the Round Table as a touchstone of twentieth-century genius seems an open question.

Parker tended to downplay the Round Table’s significance as she aged. After the group disbanded, she rendered a stinging assessment: “Just a bunch of loudmouths showing off, saving their gags for days, waiting for a chance to spring them.” At the very least, the Algonquin confabs celebrated a sense of language as theater, something that suited Parker’s attitude.

Her jaundiced barbs about booze, love, and loss continue to decorate the pages of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations. Here we find the obligatory “Men seldom make passes / at girls who wear glasses,” along with her cynical proverb, “Scratch a lover, and find a foe.” Given Parker’s copious consumption of spirits, another one-liner attributed to her sounds eminently plausible: “One more drink and I’ll be under the host.”

Funny stuff, and yet one is moved to reflect that pith isn’t an unalloyed virtue in a writer. It can make an intellect seem glancing, bent on wit rather than wisdom. Surely that’s why the masters of the form—Parker, Ambrose Bierce, and La Rochefoucauld—can have a limiting air of adolescence about them, as if they’re eye-rolling through life rather than engaging it.

But the sparks of Parker’s poetry and prose, thrown off with seemingly casual brilliance, stemmed from an exactitude as exhaustive as a jeweler’s, a precision produced by hard work.

“This was her gift: to shave complex emotions down to a witticism that hints at bitterness without wearing it on the surface,” author Michelle Dean writes of Parker.

Dean’s Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion attempts to explain Parker’s relevance to a new generation of readers. She places Parker within a line of talented cultural commentators—including Rebecca West, Pauline Kael, Joan Didion, and Nora Ephron—who “came up in a world that was not eager to hear women’s opinions about anything,” yet somehow prevailed. Dean gives Parker particular credit for advancing this tradition, since she was among its earlier pioneers. “It can be easy to forget that Dorothy Parker began publishing her caustic wit before women even had the vote,” Dean tells readers.

Another contribution of Dean’s scholarship is its simple but also easily overlooked reminder that Dorothy Parker wasn’t always Dorothy Parker.

“She was born well-enough-to-do in 1893 to a fur merchant,” notes Dean. “The family name was Rothschild—not those ones, as Parker reminded interviewers all her life. But still a respectable New York Jewish family, financially comfortable enough for Jersey Shore vacations and a large apartment on the upper West Side of Manhattan. Then her father died in the winter of 1913, devastated by the deaths of two wives and a brother who sank with the Titanic. His children inherited almost nothing.”

Parker’s troubled past gave her an unshakeable sense of life’s volatility, a reality that followed her. Parker’s first husband, Eddie Parker, was an alcoholic and morphine addict. She later married, divorced, and remarried Broadway actor Alan Campbell, who committed suicide in 1963. Parker struggled with alcoholism much of her life and attempted suicide several times.

Her acute connection with tragedy enabled Parker to speak to a generation of readers that was facing its own challenges. She came of age as a writer in the aftermath of World War I and the Great Flu Epidemic of 1918, events that caused many to question long-held assumptions about the inevitability of progress. The so-called Roaring Twenties, now celebrated nostalgically as a giddy good time, also resonated with a renewed awareness of the darker possibilities of existence.

That vision is evident in the somber notes sounded by the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, two of the decade’s literary standard-bearers, and it runs through Parker’s work, too.

Her acid fatalism can make Parker’s prose and poems hard to take in extended doses, but they’re relieved by her cunningly subversive humor, something she developed early.

She cut her teeth as a full-time journalist at Vogue, which was then a blandly conventional journal of women’s fashion, a subject of little interest to Parker. Even when handed workaday assignments like writing captions for photos of the latest apparel, though, Parker found ways to startle the status quo, as when she noted near an image of intimate wear that “brevity is the soul of lingerie.”

Her talent landed her a full-time job as drama critic at Vanity Fair in 1918, where she replaced P. G. Wodehouse. Parker’s biting reviews proved too much for the magazine, and her gig covering theater didn’t last long. But she found platforms elsewhere, perhaps most notably in the New Yorker, where Parker was a formative influence on its institutional voice. “In fact,” Dean argues, “she was far more instrumental in making the magazine’s reputation than it was in making hers.”

Parker, says biographer Marion Meade, “bestowed on the magazine a distinctive style that would become the standard for the famed New Yorker casuals.”

She wrote the magazine’s “Constant Reader” book review column for a time, coining zingers that still quiver like an assassin’s arrow. Claiming nausea from the baby talk in A. A. Milne’s children’s book The House at Pooh Corner, a mirthfully mimicking Parker reported that “Tonstant Weader Fwowed up.”

If assigned reading could make Parker feel queasy, assigned writing didn’t make her feel uniformly in the pink, either. She wasn’t, to put it mildly, the sort of scribe who embraced the notion of a friendly muse and the joy of composition.

Rather than write, Parker “claimed that she would prefer to clean out ferry boats, peddle fish, or be a Broadway chorus boy,” as Barry Day puts it in his book about her. “Instead she was—she said—‘only a hardworking woman, who writes for a living and hates writing more than anything else in the world.’”

When asked why she wrote, Parker didn’t point to artistic imperative. “Need of money, dear,” she responded in one of her oft-quoted lines. She freelanced through much of her career, which made money a constant worry.

The two best words in the English language, Parker memorably declared, were “check enclosed.” Like many writers of her era, she found financial salvation, however briefly, in Hollywood, where she and Campbell landed lucrative screenwriting projects. “In the golden age of screwball comedies, the team of Parker and Campbell were much in demand,” Meade points out. “Notable among their two dozen screenplays was A Star Is Born, not a comedy but a dramatic film for which they received an Academy Award nomination. By 1937, they were making a joint salary of $5,000 a week, a staggering amount at the height of the Depression.”

Parker welcomed the income, though she never warmed to Tinsel Town, which she described as “Sodom-in-the-Sun” and “Poughkeepsie with Palms.” One of her puckish poems was “Movies: A Hymn of Hate,” a jeremiad against the shallowness of commercial film culture. The opening two lines seem an apt summary of her feelings: “I Hate Movies; / They lower my vitality.”

Given her low opinion of the silver screen, it wouldn’t have surprised Parker that the only significant film treatment of her life, Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, is so forgettable. The title character of the 1994 production is played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, who underscores Parker’s alcoholism by slurring throughout the movie. Her lines are so garbled that when the film premiered at Cannes, viewers complained, prompting some of the dialog to be redubbed. Even so, Leigh’s Parker still comes off as something of a zombie—a crushing bore who bears little resemblance to the literary figure celebrated by her contemporaries as a hard-drinking yet urbane provocateur.

Parker’s dependence on alcohol was, indeed, a prominent part of her life and surely shortened it. She often imbibed scotch but could drink “practically anything in a pinch except gin, which, plain or mixed, made her ill,” writes Meade. “Never did Dorothy appear drunk,” she says of Parker’s Round Table days. “But she was seldom completely sober, either.”

A 1959 radio appearance with Studs Terkel that’s archived online reveals Parker’s real voice. She speaks politely and precisely, displaying the formal manners for which she was known. Woollcott, her friend from the Algonquin days, noted the contrast between Parker’s typical civility and her reputation as a firebrand: “So odd a blend of Little Nell and Lady Macbeth.”

“Standing a pert four feet eleven inches tall, cute as a bug’s ear, meant Parker was easy to mistake for some sweet little lady,” Meade observes. “Because of her ability to evoke laughter, she appeared to have few worries. . . . But still at heart she was an incorrigible pessimist who viewed life as a badly conceived, badly executed concept, a blueprint utterly gone wrong.”

What’s also obvious in Parker’s radio interview is her seemingly reflexive self-effacement. When Terkel mentions her previous work as a literary critic, she demurs. “I can’t call myself a critic, honestly,” she says. “I can only put down what I think and pray there’s no libel suit, that’s all.”

Such modesty reflected Parker’s lifelong habit of discounting her achievements. She always wished that she had accomplished more. “Her ambitions were not as small as other people thought,” Dean writes. “Real writers, she repeatedly reminded herself, write novels,” Meade says.

Parker never published a novel, though her collected poems, nearly four hundred pages in all, are still in print. They usually take the form of direct address to the reader, relying more on clever conversational turns than lyrical imagery to carry their message. That message, for the most part, is mordantly bleak, the darkness relieved by wry comedy, much like Charles Addams’s ghoulish New Yorker cartoons. Her most famous poem is “Résumé,” in which the narrator reviews various methods of suicide, concluding, “Guns aren’t lawful; / Nooses give; / Gas smells awful; / You might as well live.”

Parker’s short stories, also some four hundred pages when completely gathered, are no exercise in good cheer, either. In Parker’s short fiction, writes scholar Regina Barreca, she “depicted the effects of poverty, economic and spiritual, upon women who remained chronically vulnerable because they received little or no education about the real world—the ‘real world’ being the one outside the fable of love and marriage. But Parker also addressed the ravages of racial discrimination, the effects of war on marriage, the tensions of urban life, and the hollow space between fame and love.”

The posture of ironic detachment popularized by Parker’s Round Table period doesn’t square with the political themes suggested in her fiction and her later public stances for progressive causes.

But like many a writer styled as a cynic, Parker was, it appears, a disappointed romantic. “Her proudest moment, she always said, had nothing to do with writing,” Meade points out. “It was in Boston, one blistering August afternoon, when she was dragged off to jail for protesting the execution of the anarchists [Nicola] Sacco and [Bartolomeo] Vanzetti.”

Parker’s leftish politics got her blacklisted from Hollywood, and when she died, in 1967, she had little money. But she left her modest estate, including the rights to her literary work, to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., stipulating that the estate would pass to the NAACP in the event of his death. She’s buried in Baltimore, outside the NAACP’s headquarters.

“To me, there are only two kinds of writers—those who write badly and those who write well,” Parker said in the decade before her death. “I believe, and it is a sad belief, that any writer, no matter what he puts down, does the best that he can—oh, sure, sure, he may write what he calls dashing off something—but I tell you no matter what he writes, it is the best he can. It is the congenital curse of the writer that whatever he writes is the best that he can do.”