In 1938, as British prime minister Neville Chamberlain worked out a controversial agreement in Munich that was meant to prevent World War II, the writer E. B. White was atop his barn, installing a new set of shingles to keep it dry throughout the cold, snowy winters that visited his farm in coastal Maine.

The next year, as England and France declared war against Nazi Germany, White walked to his garage and began sorting nails. And when news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor reached his household on December 7, 1941, White noted that his wife had lost the stopper to a hot water bottle, a minor mishap that seemed, somehow, to underscore the larger disorder shaking the world to its knees.

Even so, the homely reports from White’s farm to readers of his “One Man’s Meat” essays in Harper’s Magazine seemed, at first glance, a far remove from the global conflagration causing so much suffering among millions of soldiers, sailors, and, civilians.

And yet White was the writer that many American fighting men chose to read. His “One Man’s Meat” columns, collected in a book of the same name, were a hit among the troops. “Soon my casual pieces depicting life on a saltwater farm in New England were finding their way to members of the Armed Forces in a paperback Overseas edition, and letters of thanks were arriving from homesick soldiers in distant lands,” White later recalled of those war years.

“This relieved my mind, as I had been uneasy about indulging myself in pastoral pursuits when so many of my countrymen were struggling for their lives, and for mine.”

White needn’t have worried about his relevance to the war effort. His essays—plainspoken, self-deprecating, and with a gentle but abiding skepticism about institutional authority—seemed to express the basic qualities for which his nation was fighting.

White’s farm inspired not only his essays, which are still highly regarded as classics of the form, but children’s stories, such as Charlotte’s Web and The Trumpet of the Swan, that have endured as touchstones for generations of children. His accomplishment seems all the more remarkable because, unlike so many literary geniuses, White appears to have enjoyed a relatively happy childhood, although his youth was complicated by chronic shyness that would plague him throughout his life.

Elwyn Brooks White was born on July 11, 1899, into a prosperous family in Mount Vernon, New York. He was the youngest of six children, and his father’s success as a business executive meant good things for young Elwyn and his siblings.

Elwyn “owned the first small-sized bicycle on the block, and when he was only eleven he was given a sixteen-foot, dark green Old Towne canoe that, as his father might have said, was ‘the best that money could buy,’” author Scott Elledge notes in his biography.

White’s boyhood home also included a series of memorable dogs, along with pigeons, chickens, a turkey, ducks, and geese. White loved the backyard stable, which had a hutch for his rabbits, too. His affection for animals stayed with White into manhood, leading him to the farm that became his defining landscape, and informing the tales for children still read by millions of youngsters.

“From early childhood, Elwyn found the dark and pungent stable intoxicatingly rich in romantic associations of life and death and adventure,” says Michael Sims, the author of a popular study of Charlotte’s Web. “But it was also a refuge where a thoughtful young boy could spend time by himself.” Sometimes painfully reserved, White “felt more at home with animals than with people, and he kept pigeons, dogs, snakes, polliwogs, turtles, rabbits, lizards, singing birds, chameleons, caterpillars, and mice,” author Dale Kramer wrote.

As a college student at Cornell, White edited the campus newspaper, but a brief stint at the Seattle Times after graduation convinced him that daily journalism wasn’t for him. His poetic sensibility didn’t square with conventional news reporting, and his exacting, gimlet style was hard to pull off under the pressure of constant deadlines. Like many young dreamers, he eventually migrated to New York City, taking a series of unsatisfying jobs in advertising and freelance journalism. His lyrical worldview didn’t seem to have a natural home.

Then, in a providential turn, the New Yorker opened its doors in 1925, creating a venue that was tailor-made for White’s jeweled prose. Along with contemporaries such as James Thurber and Robert Benchley, he became one of the magazine’s formative voices. Harold Ross, the magazine’s first editor, quickly realized White’s potential.

“White was an individualist and an admirer of nature, especially of Henry Thoreau’s writings,” Kramer, a historian of the New Yorker’s early days, has written. “Whenever he went anywhere he packed his Walden as naturally as his toothbrush. But he was aware that solitude was to be found in the city too. His life had fitted him almost perfectly for the wide-eyed yet deep-felt eagerness that Ross needed.”

Gotham, teeming with life, ironically seemed a place where White could be inconspicuously alone. Years later, White elaborated on that contradiction in a famous 1948 essay, “Here Is New York”:

On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy. It is this largess that accounts for the presence within the city’s walls of a considerable section of the population; for the residents of Manhattan are to a large extent strangers who have pulled up stakes somewhere and come to town, seeking sanctuary or fulfillment or some greater or lesser grail. The capacity to make such dubious gifts is a mysterious quality of New York. It can destroy an individual, or it can fulfill him, depending a good deal on luck. No one should come to New York to live unless he is willing to be lucky.

White’s essay about New York came to the minds of many Americans after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack against the World Trade Center. Here’s White, writing more than a half a century before that fateful day:

The subtlest change in New York is something people don’t speak about much but that is in everyone’s mind. The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the underground passages into lethal chambers, cremate the millions. The intimation of mortality is part of New York now: in the sound of jets overhead, in the black headlines of the latest edition.

White’s alertness to New York’s vulnerability to attack wasn’t the only time that his observations proved prophetic. In the 1930s, after White attended a demonstration of a fledgling technology called television, he immediately saw through the razzle-dazzle and understood how the medium would change society:

Television will enormously enlarge the eye’s range, and, like radio, will advertise the Elsewhere. Together with the tabs, the mags, and the movies, it will insist that we forget the primary and the near in favor of the secondary and the remote. More hours in every twenty-four will be spent digesting ideas, sounds, images—distant and concocted. In sufficient accumulation, radio sounds and television sights may become more familiar to us than their originals. A door closing, heard over the air; a face contorted, seen in a panel of light—these will emerge as the real and the true; and when we bang on the door of our own cell or look into another’s face the impression will be of mere artifice.

Literary critic Clifton Fadiman suggested that White could see the future so clearly because he had such a sharp view of the present. “The spur of Mr. White’s realism is the fact that he has the eye of a poet, a poet being a man who sees through things,” Fadiman noted. “Having the eye of a poet he is intensely aware of our taken-for-granted environment. He is aware of the millions of substitutes for things, the millions of substitutes for ideas, the millions of substitutes for emotions, the millions of substitutes for human beings. Out of this awareness the sweet and bitter of his prose continually wells.”

By 1938, White seemed to be at the top of his game. In a country still wracked by the Depression, he enjoyed a well-paying job at the New Yorker and the admiration of his peers. He had married New Yorker editor Katharine Angell in 1929. The Whites’ family included Nancy and Roger Angell, Katharine’s children from a previous marriage. Roger Angell eventually became a New Yorker staffer himself. The Whites’ son Joel was born in 1930.

But touched by a midlife crisis of sorts, White decided to leave the New Yorker—and New York itself—and move to a saltwater farm in rural Maine. Katharine, in spite of her stature as one of the most influential editors in America, agreed to go along, striking an arrangement with the New Yorker that allowed her to do some editing work long-distance through the mail.

White had no clear plan for making a living. But shortly before White’s departure from Manhattan, Harper’s editor Lee Foster Hartman asked White to write the monthly essays about rural life that would become “One Man’s Meat.” The essays satisfied White’s longstanding desire to write in the first person—something that the New Yorker, with its fetish for the editorial “we,” hadn’t allowed him to do. Farm life also renewed White’s imagination and sense of possibility.

After a few years, White returned to the New Yorker, but his real home remained in Maine. “Once in everyone’s life there is apt to be a period when he is fully awake, instead of half asleep. I think of those five years in Maine as the time when this happened to me,” White wrote of his move to New England. “Confronted by new challenges, surrounded by new acquaintances—including the characters in the barnyard, who were later to appear in Charlotte’s Web—I was suddenly seeing, feeling, and listening as a child sees, feels, and listens. It was one of those rare interludes that can never be repeated, a time of enchantment. I am fortunate indeed to have had a chance to get some of it down on paper.”

In staging his daring retreat, White could look to a fellow New Englander, Thoreau, for inspiration. In “A Slight Sound at Evening,” his 1954 tribute to Thoreau, White quoted admiringly from Thoreau’s journal: “A slight sound at evening lifts me up by the ears, and makes life seem inexpressibly sweet and grand. It may be in Uranus, or it may be in the shutter.”

Thoreau’s gift for divining profound insights from the unassuming rhythms of domestic life is also what makes White’s writing so sublime. His 1940 essay about cars isn’t really about automobiles, but about how consumers blindly follow the whims of industry—and, in the process, condition themselves to be passive citizens, too. Here, in a single sentence, he tangibly describes how individuals quickly get lost within institutions: “The ultimate goal of automobile designers is to produce a car into whose driving seat the operator will disappear without a trace.”

In “Once More to the Lake,” perhaps his most widely anthologized essay, White recalls returning with his son to the same summer vacation spot that he once enjoyed with his own father. Throughout most of the essay, time seems suspended, the experience unblemished by the passage of years. But then, while watching his son throw on some wet swimming trunks for an afternoon swim, White realizes that his own boyhood has passed, leaving him a middle-aged man in the shadow of mortality. Here’s how White expresses that sentiment in a handful of words: “As he buckled the swollen belt, suddenly my groin felt the chill of death.”

That gift for distilling complex ideas and feelings so concisely is the ideal at the center of The Elements of Style, a handbook on writing that White updated from a manual first printed by one of his Cornell professors, William Strunk, then published in 1959. The book, known affectionately by its fans as “Strunk & White,” has sold millions of copies and become a cultural fixture. White embraced Strunk’s cherished dictum, “Omit needless words.” As Strunk wrote:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

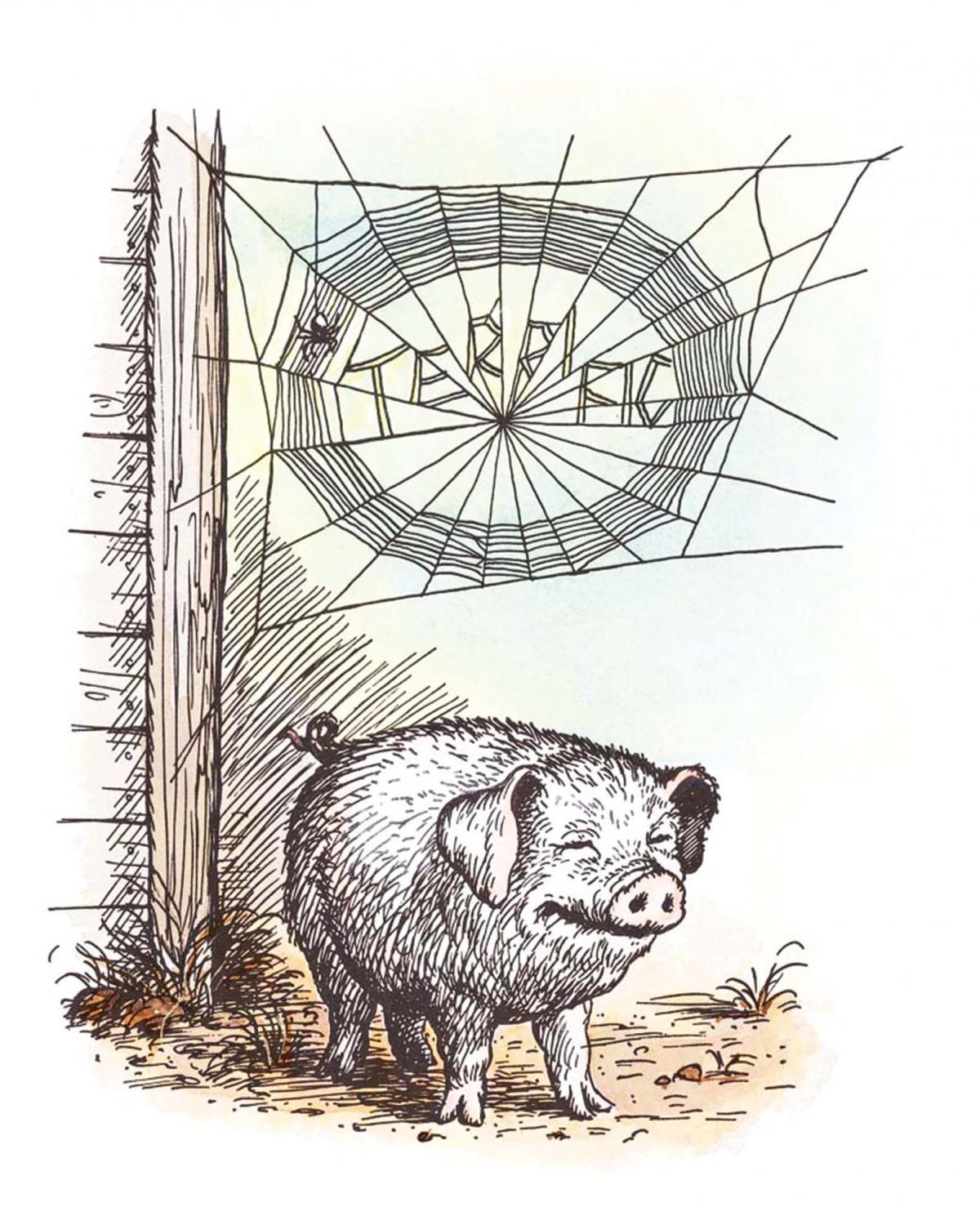

White’s basic credo of writing also expressed itself in Charlotte’s Web, his classic children’s tale in which the title character, a highly literate spider, saves a pig from slaughter by spinning words of appreciation above its head. The gesture seems miraculous to human observers, but White suggests that the real miracle isn’t Charlotte’s web trick, but the abiding gratitude that inspired Charlotte to write in the first place. White thought that the best writers were “recording secretaries” for wonders large and small. “As a writing man, or secretary,” White once confessed, “I have always felt charged with the safekeeping of all unexpected items of worldly or unworldly enchantment, as though I might be held personally responsible if even one were to be lost.”

He took his obligations as a writer seriously: White could be deeply self-critical, endlessly revising his essays and stories until, paradoxically, the end result seemed casual and conversational. The intensity of his vision sometimes sharpened his nerves. Periodically, White suffered from anxiety and hypochondria.

White’s troubles, and the graceful prose he managed to craft despite his challenges, are what make him so admirable, according to Susan Allen Toth, a master essayist in her own right. “Thinking of White as a man who knew fear, anxiety and self-doubt, but who still reveled in life, I continue to want him as a guide,” Toth wrote. “It is not easy to write prose, or live a life, with his humor, resilience and staying power.”

Despite his worries about decline, White’s physical health remained quite good into advanced age. Not until his eighties did White really begin to slip, as he showed symptoms of the Alzheimer’s disease that would eventually claim his mind and body. In his final weeks, when White was bedridden, his son Joel would visit each evening and read to him, sometimes from White’s own books. With his mind failing, White’s self-consciousness faded, too. He could hear—and enjoy—his own prose as a reader, not as a critic.

That appreciation is shared today by millions of readers in the United States and abroad. E. B. White died on October 1, 1985, at age eighty-six, but most of his books remain in print, and he continues to attract new fans.

In spite of his exceptional talent, White endures because he so aptly expressed the joys and sorrows of the common man. White “took pains not to be grand and all for naught,” Washington Post columnist Henry Mitchell noted after White’s death. “He wound up grand for all his avoidance of grandeur, and the more he avoided noble and elevated style the more convinced his readers were that he was noble—a word not always trotted out for writers of short and casual pieces. . . . He has been called the best American essayist of the century, though most of his readers possibly have wondered who the competition was supposed to be.”

*This article was updated on January 24, 2014, to correct a misattributed quotation.