Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) is the central figure in the German literary canon. Poet, novelist, playwright, and scientist, he is to the German language what William Shakespeare is to English-speaking cultures, only more so. The fact that such a protean, polymathic, and “great” figure emerged on the doorstep of the modern world, rather than in a faraway era, makes Goethe feel less mythical, more like a contemporary, and more like one of us. Indeed, Goethe spoke and wrote in what is recognizably modern German instead of a language that may sometimes require guidance to fully grasp, even for native speakers, as is the case when students approach Shakespeare’s Elizabethan English for the first time.

Goethe’s influence went far beyond Germany’s borders. From the early nineteenth century onward, Goethe served as a sage and literary icon for the Anglo-American world, where his popularity exceeded that of British and American authors. His English-language champions—from Mary Wollstonecraft to George Eliot, many were women—included several important or soon-to-be important critics and thinkers.

Thomas Carlyle, the Scottish historian and critic, urged aspiring writers in early Victorian Britain to adopt Goethe as a role model. Instead of simply praising Goethe’s writing, Carlyle offered up a full-blown cult of personality. Look closely and one can see in it the blueprint for an ideology of hero-worship that becomes hugely influential in Europe and then America in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Goethe’s reputation in Britain did not take shape in response to the lyrical Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) or the magisterial Faust (1808). Instead, it grew out of the controversy surrounding his personality, ethics, and character. From the first English translation of Werther in 1779 to Carlyle’s translation of Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship in 1824, criticism of Goethe in Britain and North America was inflected by what English literary historian George Saintsbury later derided as “anthropological” interpretations and moralistic readings projected back onto the author.

Not only was Goethe condemned on all sides for his multiple love affairs and unblushing treatment of carnal longing in his poetry and prose, but he was also deemed objectionable for his protagonists who committed suicide (Werther) and bartered their soul in exchange for heightened experience (Faust). Similarly, Goethe’s pantheistic celebration of nature was deemed as blasphemous as his wide-ranging intellectual curiosity and unlimited pursuit of self-knowledge. In addition, Goethe was considered unfit as a cultural role model in the fledgling American republic for his willing acceptance of a knighthood in return for service to the autocratic prince of Saxe-Weimar.

Goethe, in a way, invited such responses. In his own criticism, he gave free rein to the biographical impulse. In Gespräche mit Goethe (Conversations with Goethe) (1836), for example, German poet and author Johann Peter Eckermann notes Goethe’s assertion that

personality is everything in art and poetry; nevertheless, there are many weak personages among the modern critics who do not admit this, but look upon a great personality in a work of poetry or art merely as a kind of trifling appendage. However, to feel and respect a great personality you must be something of one yourself.

A perusal of Goethe’s comments, letters, and criticism confirms that he only rarely discusses a specific work and its literary characteristics; instead, his interest in the writer’s personality nearly always supersedes textual analysis or any explicit discussion of aesthetic qualities. Thus, a poet’s personality becomes one of the chief organizing principles in the cultural life of nineteenth-century Europe.

Wherever Goethe was read, critiqued, and translated, one found the basis of oppositional cultures. This was especially true in Great Britain and New England. Bound by religious heritage and the experience of pilgrimage for intellectual and spiritual enrichment, the British mediators of German culture were, however, divided from their Boston cousins by differences in class and social influence. In New England, descendants of the original Puritans were socially dominant. In Britain, Dissenters from the Anglican majority, Scots Presbyterians, and other sectarians were politically and socially marginalized, as were women, Roman Catholics, and Jews. Nonetheless, members of all these peripheral groups formed the nucleus of the German-trained intelligentsia in Britain.

Moreover, the writings of these outsiders, chiefly translations and criticism, revealed connections between an English-speaking enthusiasm for Goethe, the American effort to declare cultural independence from Great Britain, and the migration of women writers from the margins of cultural life to its center. Margaret Fuller’s (1810–1850) efforts to critique and translate German literature and her emergence as one of the most important literary figures of the time are inseparable. And the arc of her career is similar to that of other Anglophone women writers, such as Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), Sarah Austin (1793–1867), George Eliot (1819–1880), and Edith Wharton (1862–1937), all of whose mature writings owed something to earlier apprentice work reviewing and translating German literature of the period.

Mary Wollstonecraft

The popularity and impact of British literature in German-speaking countries has been well documented. But scholars and critics of British literature have long resisted acknowledging the influence of German literature and thought on British culture. This may have had something to do with the fact that women and other cultural outsiders played leading roles as cultural intermediaries of German literature into English and a prior commitment to the iconic position of the author at the expense of those cultural networks on which writers depend for inspiration and promotion.

Consider, for example, the writing generated by friends and admirers of William Godwin, whose London bookshop opened in 1805 on Hanway Street, becoming the center of radical resistance against the British government. All this must be viewed in the context of the mediating activity of Godwin’s first wife, the philosopher and champion of women’s rights Mary Wollstonecraft, among others.

Wollstonecraft’s major achievement as a translator of German appeared in 1790. Elements of Morality, for the Use of Children was freely adapted from the German text by Christian Gotthilf Salzmann (1744–1811), whose influence as a writer on education was noted by Goethe and others. His Moralisches Elementarbuch was reprinted throughout the nineteenth century, and the 1785 edition was reissued as recently as 1980. Wollstonecraft’s Elements of Morality is not a mechanical translation or mere hackwork. On the contrary, it represents a pathbreaking exercise in transposing a foreign text into a domesticated form for British readers. There are strong ideological and stylistic ligatures bonding Elements of Morality to Wollstonecraft’s original works of a pedagogical and didactic character, from Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) to the seminal A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Moreover, Wollstonecraft’s novel Young Grandison (1790) is a reworking of a foreign text, De kleine Grandison (1782), a novel by the Dutch writer Maria Geertruida van de Werken (1734–1796), which was itself an adaptation of Samuel Richardson’s Correspondence Primarily on Sir Charles Grandison (1750–1754).

Sarah Austin and Margaret Fuller

Sarah Austin was an uncannily accomplished translator and a key figure in elevating Goethe to the status of the “strong poet” with whom Anglo-American writers grappled from the 1780s to the middle of the nineteenth century. Her translation of various firsthand accounts of Goethe, entitled Characteristics of Goethe from the German of Falk, Von Müller and others (1833), fed the British reading public’s burgeoning appetite for any contact with the poet whom Carlyle a few years earlier made not only famous but a cult figure.

In 1841, Austin published another influential text, Fragments of German Prose Writers, which contains extensive notes and around a hundred pages of background on various authors. The notes and profiles are an attempt to articulate the canon of German prose and women writers. Austin later published Germany from 1760 to 1814, an original study of German culture, manners, and institutions, which appeared contemporaneously with “The Natural History of German Life,” one of George Eliot’s most insightful essays on German culture.

In 1839, just three years after its initial publication in Germany, Margaret Fuller’s translation of Eckermann’s Conversations with Goethe appeared, accompanied by the first lengthy critical biography of Goethe in any language, in which Fuller sought to distance herself from the partisan politics of Goethe’s reception in the English-speaking world. Fuller offered a vision of the direction she hoped American literary criticism would take:

I am not fanatical as to benefits to be derived from the study of German literature. I suppose, indeed, that there lie the life and learning of the century, and that he who does not go to these sources can have no just notion of the workings of the spirit in the European world these last fifty years or more.

Fuller was strongly attracted to Goethe’s imaginative writings (“of German writers the most English and the most Greek”), even if she expressed qualms concerning his personal life. After the Conversations, she translated Goethe’s verse drama Torquato Tasso (1790), which appeared in the posthumously published collection of her work—Art, Literature and the Drama (1859). Fuller also translated Die Günderode (1840), the fictionalized correspondence between the German Romantic poets Bettina von Arnim and Karoline von Günderrode (1780–1806). In the translator’s preface, Fuller explains why she was drawn to this extraordinarily revealing work of intellectual and emotional intimacy:

And not only are these letters interesting as presenting this view of the interior of German life, and of an ideal relation realized, but the high state of culture in Germany which presented to the thoughts of those women themes of poesy and philosophy as readily, as to the English or American girl come the choice of a dress, the last concert or assembly, has made them expressions of the noblest aspirations, filled them with thoughts and oftentimes deep thoughts on the great subjects.

In the conclusion to her translator’s preface to the Conversations, Fuller noted that the remarkable explosion of cultural activity in Germany over the previous 85 years was directly related to the “transfusion of such energies as are manifested in Goethe, Kant, and Schelling, into these private lives.”

Published in another posthumous collection of Fuller’s writings, Life Within and Without (1860), is an essay simply entitled “Goethe,” in which Fuller offers guidelines for a typological interpretation of the German poet’s life for readers who accepted him as their cultural savior:

Faust contains the great idea of his life, as indeed there is but one great poetic idea possible to man—the progress of a soul through the various forms of existence. All his other works . . . are mere chapters to this poem. . . . Faust, had it been completed in the spirit in which was begun, would have been the Divina Commedia of its age.

Fuller’s essay was to have been merely the germ of a full-scale biography of Goethe, which would have predated G. H. Lewes’s Life of Goethe (1855), the first such biography in any language, by two decades. The loss to American literature and to the interpretation of Goethe, when Fuller drowned in a shipwreck in 1850, is incalculable.

Importing Goethe and German culture into New England answered a deep-seated need for greater worldliness and personal growth in a direction away from the Anglophone self. For Margaret Fuller and her fellow mediators in New England, the encounter with the great, compelling example of Goethe was inseparable from their own quests for author’s laurels. But as enriching and enabling as the cultural imports of Germany proved to be, their transmission was disruptive to the status quo in New England. Goethe, and one’s attitude toward him, became a litmus test for intellectual politics in New England. The ideas spawned in Weimar, Jena, and Göttingen were not the products of a society moving toward popular democracy. They were, instead, ideas nourished by aristocratic patronage in an authoritarian (and anachronistic) ministate that was highly invested in the assertion of German culture in defiance of French domination of Western Europe. It is, indeed, paradoxical that an American literary movement like Transcendentalism should have been shaped, in large part, by the emulation of Goethe, an ennobled cultural hero who made no secret of his indifference or even hostility to emerging democratic institutions.

Ralph Waldo Emerson found Goethe’s aristocratic sensibility difficult to reconcile with his admiration for the great poet’s writings. The code word used by critics and admirers was Goethe’s “morality.” This identification spoke to the conflict between the values of New England society built on a Puritan religious and ethical foundation and the dominant cultural movement emerging in Germany modeled on the aesthetic life as personally embodied by Goethe. The problem confronted by Emerson and Fuller was paradoxical: How were they to engender an American cultural revolution devoted to individual development based on an imported aristocratic aestheticism? Emerson’s ambivalence was ultimately overcome, as evidenced by the publication of the essay “Goethe: Or, the Writer” in Representative Men (1850).

Though Carlyle had called Goethe “the soul of the century,” Emerson began his study of the German writer by confiding in his journal that “the Puritan in me accepts no apology for bad morals in such as he.” In his famous essay of 1850, however, Emerson’s tone is profoundly changed. He now considers Goethe “a poet of prouder laurel than any contemporary. . . . The Greeks said that Alexander went as far as Chaos; Goethe went, only the other day, as far; and one step farther he hazarded, and brought himself safe back.” Goethe wrought this change in Emerson by treating one’s personal strivings as the deepest and most authentic form of self-knowledge. “If we live truly, we shall see truly,” Emerson wrote. “The soul becomes . . . God is here within.”

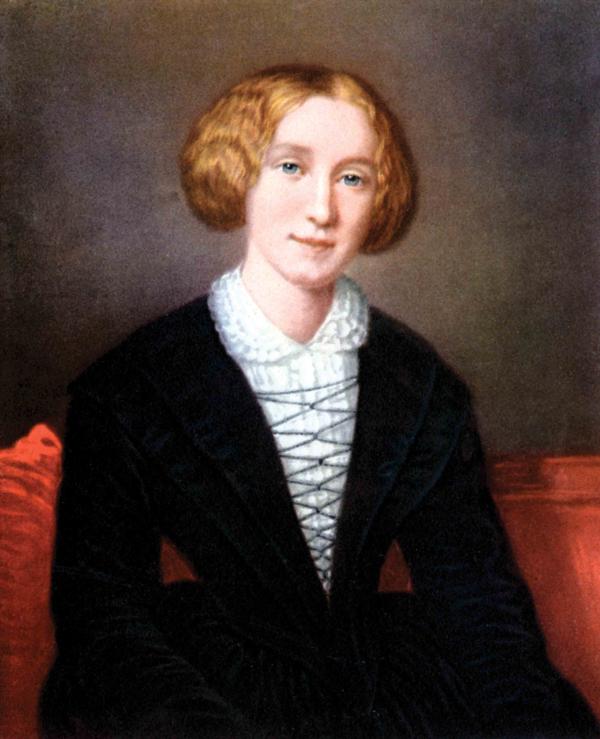

George Eliot

The Anglophone writer whose achievement is most closely associated with Goethe is George Eliot. In 1854, on the eve of her scandalous elopement to Germany with the still-married George Henry Lewes, who was at the time writing the first biography of Goethe, Mary Ann Evans had not yet adopted her famous pen name or published her first work of fiction. What she had accomplished, however, was not inconsiderable. Even if, with the publication of Middlemarch in 1871, she had not proven herself to be the preeminent Victorian novelist, her mediating activity as a translator and reviewer of German books (e.g., David Friedrich Strauss’s The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined (1846) and The Essence of Christianity (1854) by Ludwig Feuerbach) would have established her credentials as one of the most important interpreters of German culture since Thomas Carlyle’s engagement with Goethe in the 1820s and 1830s. The major essays and reviews written during Eliot’s sojourn in Germany include “The Morality of Wilhelm Meister” and “The Natural History of German Life.”

At a time when even rudimentary knowledge of German was still uncommon in Britain, Eliot had acquired expert skill in the language on her own. Without a university education, she had accomplished what, in a famous essay, “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time,” Matthew Arnold opined that the leading British writers of the nineteenth century most emphatically had not: immersion in the larger currents of European ideas. As the product of a radically different cultural orientation (German as opposed to Greco-Roman) and literary apprenticeship (translating and reviewing) from that of her male contemporaries, Eliot was an exception to the typical intellectual insularity of male writers in Britain. Having been denied the classical education that formed the training of men and permitted only the most basic schooling and superficial accomplishments, she and other leading Anglophone women writers—Wollstonecraft, Austin, and Fuller—nonetheless acquired an intellectual tradition of their own, based not on Latin and Greek but on contemporary German authors and ideas.

To paraphrase Friedrich Nietzsche, as Harold Bloom does in The Anxiety of Influence: “When one hasn’t had a good father, it is necessary to invent one.” Women writers in Britain had little choice but to exchange the indifferent culture of their birth for a foreign, nurturing cultural parent. Put another way, the domestication of German culture was, for women writers, a means of acquiring cultural capital from an indifferent, even hostile, dominant culture, its publishing institutions, and the reading public formed by them. In a letter to Carlyle in July 1827, Goethe intimated that the vocation of the translator as cultural intermediary is indeed sacred: “So ist jeder Übersetzer ein Prophet seinem Volke” (Every translator is a prophet to his own people).

Lewes could not have chosen a better collaborator when he invited Eliot to accompany him to Weimar in 1854. The pretext for the journey was to permit Lewes to research his biography of Goethe, but Germany also served as a much-needed refuge and destination for an unofficial honeymoon. Once in Weimar, the couple quickly established their work routine: Lewes composed, and Eliot polished his drafts and provided the translations from Goethe’s works cited in the text. Ironically, by leaving aside her reviewing and abandoning her contacts in the London literary world and immersing herself in the writings of Goethe, Eliot acquired the wherewithal to become a novelist. The transformation of Mary Ann Evans, maid-of-all-literary-hackwork, into George Eliot, literary giant, can be attributed to what Virginia Woolf called “the great liberation which had come to her with personal happiness.” Indeed, it was in Weimar, in the empowering shadow of Goethe, a fellow transgressor of bourgeois morality, that Eliot achieved emotional and intellectual fulfillment. This pilgrimage to the epicenter of German culture, more than any other episode in her life, was decisive in shaping her destiny as a writer of original fiction. Weimar offered Eliot the opportunity to come into close proximity with the greatest cultural figures of the day, to escape the treadmill of translating and reviewing, and to explore new avenues of self-development. In the process, she discovered previously untapped reserves of self-confidence and ambition that inspired a radical reconstruction of her identity.

In Weimar, Eliot and Lewes were welcomed in the best homes and salons, where they established lasting friendships with leading German cultural celebrities, including Ottilie von Goethe, the writer’s daughter-in-law, the composer Franz Liszt, and Johann Peter Eckermann, Goethe’s secretary. Eliot’s travel journal records her surprise at being openly received in polite society in Germany, something she could never expect on their return to London. The burghers of Weimar, she learned, were incredibly tolerant of irregular personal relations. Goethe and Christiane Vulpius, mother of Goethe’s only child, August, lived together for years before marrying in 1806. While still married to other people, Liszt and Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein openly cohabited. Of German manners and morals, Eliot noted at the time that “the Germans, to counterbalance their want of taste and politeness, are at least free from the bigotry and exclusiveness of their more refined cousins” in Britain.

The sacrifice of friends and family who turned their backs on her at the news of her flight to Weimar was undoubtedly great, but Eliot may have come to deem this loss bearable because something miraculous occurred in Germany. For it was in Weimar, where she forfeited her “good name” for the sake of love, that Eliot morphed from a drudge, anonymously translating and reviewing, to a writer who would produce some of the century’s greatest novels. Weimar, as it turned out, was a shape-shifting place where identities were emended, altered, and exchanged. Goethe had managed a similar trick, metamorphosing from the author of Werther, the ultimate adolescent primal scream, to emerge as Europe’s last true polymath and the nineteenth century’s preeminent man of letters. In contrast to Eliot’s native Britain, which was, as Samuel Johnson and John Keats lamented, a conspicuously poor mother to her literary offspring, Germany was the incubator of genius, who nurtured her poets while tolerating their foibles.

Of all the geniuses based in Weimar or whose ghostly presence could still be felt in the picturesque town, Goethe exercised the most far-reaching influence on Eliot’s fiction. With Middlemarch, Eliot returned to her roots, the intellectual atmosphere and the preoccupations of her “Weimar period.” The best clue to Eliot’s emulation of Goethe in Middlemarch is displayed first by her use of Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1795) as a template. Secondly, the character Will Ladislaw is remarkably similar to his namesake Wilhelm. During her sojourn in Weimar, Eliot experienced firsthand the German idealization of the artist. It was in Germany that untitled and penniless Ladislaws could become genuine rather than alienated Shelleys and Byrons. In Middlemarch, Eliot addresses the characteristic dilemma confronted by the Bildungsroman (novel of personal growth): to represent the development of a complex personality at a time when the older, aristocratic values are threatened by an increasingly industrialized capitalism and mass democracy. Following Goethe’s example in Wilhelm Meister, Eliot poses the problem to be confronted by her protagonists: Can a person still be the architect of their own experience? Can circumstances be altered to allow for the realization of epic ambitions? Can Dorothea Brooke, Tertius Lydgate, or Will Ladislaw bridge the divide between what is given and what can be achieved by sheer willpower or fantasy?

Initially, it seems that Dorothea’s task is identical to Wilhelm Meister’s: They seek to reconcile the poetry of the heart with the outer conditions of life as they find their way in a murky moral universe. But this course of action, the conventional arc of the Bildungsroman, turns out to be an utter impossibility for Dorothea. She is incapable of altering her social milieu. Instead, it changes her, obliterating her idealism and thwarting her epic ambitions. Rather than affording Dorothea opportunities for self-realization in altruistic schemes, the social pressures inherent in Middlemarch clip her wings just as surely as they corrupt the novel’s Icarus figure, Ladislaw, by turning him into a fortune hunter. The possibility of finding personal happiness in a conventional marriage, if not in heroic martyrdom, was an option Eliot herself was never given. The conclusion of Middlemarch therefore reflects a fantasy of the author, who could not overcome her status as a pariah in British society.

Ultimately, Middlemarch embodies a rejection of the definition of Bildung established in Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, where we see the formation of the protagonist up to the moment when he ceases to be egoistic and becomes socially centered and begins to shape the self for altruistic purposes. For example, Wilhelm ultimately gives up the wandering life of an itinerant actor to become a physician. But in the world of Eliot’s novel such growth is not attainable. The mere selection of St. Theresa of Avila as the novel’s emblem or dedicatee, a powerful example of thought and feeling translated into significant action, anticipates Dorothea’s ultimate failure and suggests that the novel is, in fact, an anti-Bildungsroman. The implication is, of course, that the epic life is no longer possible in the modern world of early Victorian Britain. As indicated in the novel’s denouement, all that remains for Dorothea is withdrawal from society.

Another element of the new social reality that is explored in Middlemarch is the emergence of the modern intelligentsia as a distinct class. Represented by Will Ladislaw, this new class is severed from power and alienated from respectable society. In contrast to Dorothea, Will, a figure who walks straight out of German Romanticism into the harsh light of a realistic novel, is the true, classic Bildungsroman protagonist as well as Eliot’s homage to Goethe’s eponymous Wilhelm. Unlike Dorothea or Lydgate, whose philanthropic vocations are well established, Will’s pathway remains in formation. He is still seeking the proper outlet for his talents, and his experimentation runs the gamut from pursuing art in Rome to dabbling in local politics as Mr. Brooke’s campaign manager and press attaché. His development is, however, interrupted when he falls in love with Dorothea and embarks on a conventional family life. As a consequence, Will exchanges the questing pursuit of a meaningful life for the settled, trivial existence of a bourgeois, a fate incompatible with his previous identity “as a kind of Shelley” or “a Byronic hero.”

As crucial as interacting with Goethe’s works was to Eliot’s emergence as a novelist, in Middlemarch we see that Goethe’s worldview and the values associated with it (which emphasize individual growth from self-absorption into sympathetic beneficence) are not suited for the new age dominated by opportunistic cynics like Bulstrode and their collaborators like Lydgate. Goethe, the enabler of the rise of an alternative culture that would challenge the patriarchy for literary supremacy, had a hand in fostering the enduring achievement of Wollstonecraft, Fuller, and Eliot—among his chief British and American admirers. Their origins as cultural outsiders and the vehicle of their rise to fame—mediating Goethe—may have been obscured by time, but it bears remembering how such unlikely alliances yielded such a rich literary harvest.