She was thirty-four years old, although she claimed to be about a decade younger.

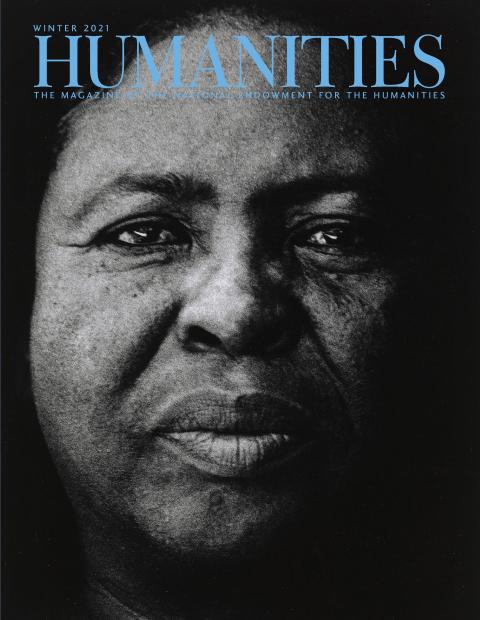

By her own admission, she had a voice too big for polite company, a tendency “to stand and give battle,” and a roll and ramble to her step that she said came from having been taught to walk by a sow hog. Her Barnard class photograph had her near the center of the frame but half hidden by a tree branch, “a dark rock surged upon, overswept by a creamy sea,” as she described herself—the college’s only African-American student. A recent migrant from Florida, she had bounced from one pursuit to another: as a dresser with a traveling Gilbert and Sullivan company, then a manicurist, then a night-school attendee. In a room of people just back from some foreign expedition, the most arresting thing about her was the name one of her mother’s friends had given her—Zora. No one knew where it came from, but there was suspicion that it had been swiped from a Turkish cigarette label.

Hurston slipped easily into the galaxy of writers, publishers, and wealthy white philanthropists, many of them women, who formed the essential patronage network for New York’s budding Black artists—the “Negrotarians,” as Hurston dubbed these supporters. That summer she managed to garner the second prize in a literary contest run by Opportunity. At the awards dinner, she met Annie Nathan Meyer, the founding benefactor of Barnard, who offered to arrange a place for her at the college during the next academic year, along with financial support. Hurston was also introduced to one of the first-place finishers, a man from the Midwest, ten years her junior but already acclaimed for his poetry. In Langston Hughes she found an immediate traveling companion within the world she had first encountered at Howard, a swirl of ideas and experiment, of words that poured out hot onto the page. It was all an unexpected windfall—the place at Barnard as well as the prospect of becoming a serious writer at the same time—especially given her middling grades and unfinished bachelor’s degree from Howard. She decided to enroll that fall.

With the blessing of Meyer and of the college’s dean, Virginia Gildersleeve, Hurston was almost immediately a person you needed to say you knew. Young women fell over one another to propose lunch. Hurston knew she was a whetstone for sharpening one’s progressive sensibility, a role she would reprise virtually every time a white benefactor took an interest in her advancement. “I became Barnard’s sacred black cow,” she later wrote. She had already perfected her signature form: a retiring standout, an obsequious bullhorn, a loud, brash, and brilliant self-doubter—“cross eyed, and my feet aint mates,” as she wrote to the poet Countee Cullen not long after arriving in Manhattan.

By the end of 1925, her former professor Alain Locke had selected one of her stories, along with work by Hughes and other young writers, to appear in a volume he was editing titled The New Negro. The book would stand as a kind of signal fire for the Harlem Renaissance, a sweeping experiment in redefining Blackness in a country that had been built on defining it for you.

Hurston lived mainly on 131st Street, although she moved frequently, and reveled in the circle of writers and artists clustered around the small journals and Saturday evening parties shaping the new cultural movement: Cullen and Hughes, her essential partner; the actor and singer Paul Robeson; the writers Arna Bontemps, Dorothy West, and Wallace Thurman; the heiress and impresario A’Lelia Walker; the white writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten, whose portraits became a kind of celluloid monument to a brief, burbling moment, a time when “the Negro” was more in vogue than at any previous point in American cultural history. Hughes remembered Hurston as “certainly the most amusing” of these contemporaries, “full of side splitting anecdotes, humorous tales, and tragic-comic stories, . . . who had great scorn for all pretensions, academic or otherwise.”

She seemed to know everyone. Hurston was a real writer, and she made sure people knew it. At a Barnard luncheon, she hosted her friend and sometime patron Fannie Hurst, a best-selling novelist. “It made both faculty and students see me when I needed seeing,” she told Hurst in a letter. Hurston’s writing was already being published in the leading Black periodicals, even if her term papers and exams suffered in the process. It seemed hard to find a major party north of Central Park where she wasn’t present, smoking cords of Pall Malls, dressed in bright scarves, crackling beads, or anything else that would turn heads when she swept into a room.

Still, traveling the distance between a Barnard lecture hall and a Harlem rent party was like shedding a skin, or perhaps slipping into one. Both worlds had their own constraints. For older Black intellectuals like Locke and DuBois, the blossoming of African-American literature was not simply a matter of art. It was the leading edge of what might become a broad reevaluation of Black potential—proof positive that African Americans could produce great work that spoke not just to their own condition but to general problems of humanity. “I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda,” DuBois wrote in 1926. Art would be liberating not in the sense that Black voices would at last be heard but rather that Black writers would now be seen as intellectuals with common claim to universal themes. Race was a route into art, and art was an escape from a racial straitjacket. Elevation, advancement, refinement, polish—these were the keys to proving oneself before the white cultural establishment and staking out a version of Blackness that was stylish, bold, urbane, and modern. All these qualities were what was meant to be new about the work showcased in Locke’s The New Negro.

But Hurston was skeptical. She chafed at the idea that Black experiences had to be pronounced worthy of being expressed in art rather than be depicted exactly as they were: in rounded vowels and her own booming voice, with cutups and jokes and ecstatic prayers and poor man’s food, through grammars and vocabularies that contained their own brand of genius. Hughes and other younger writers shared some of her views, but they sometimes found her personal style grating, even offensive. She could take things too far, they thought. “To many of her white friends, no doubt, she was a perfect ‘darkie,’” Hughes later said, “in the nice meaning they give to the term—that is a naïve, childlike, sweet, humorous, and highly colored Negro.” Speaking for the people didn’t mean you always had to speak like them.

Within only a few months Hurston emerged as the Harlem Renaissance’s greatest internal critic. She had grown up with supreme confidence in the Eatonville version of herself—in a town where it was possible to be both Black and in charge—and for all its pretensions to progress, Harlem wasn’t quite that, she felt. A person new to the city could climb out of the subway at 135th Street and find a world where every job was held by a person of color, from the policeman to the butcher to the schoolteacher. But its artists seemed intent on trumpeting that fact as somehow unusual. “Negroes were supposed to write about the Race Problem. I was and am thoroughly sick of the subject,” she later wrote. “My interest lies in what makes a man or a woman do such-and-so, regardless of his color. It seemed to me that the human beings I met reacted pretty much the same to the same stimuli. Different idioms, yes. . . . Inherent differences, no.” It was a mental framework that she was gradually picking up at Barnard, a fancier way of saying what she had, from her earliest days, thought about herself: that she was born “a child that questions the gods of the pigeon-holes.”

Hurston was majoring in English, but when a college adviser suggested that she broaden her coursework, she signed up for a class with Gladys Reichard. Hurston’s story was that Reichard called one of her papers to Franz Boas’s attention. More likely, in the small circle of fieldworkers and lecturers surrounding Boas, Hurston couldn’t resist being caught up in the enthusiastic wave. If she had arrived in New York as a would-be writer, after only a few months at Barnard she was coming to see herself as a social scientist, too, a budding Elsie Clews Parsons or Ruth Benedict. She likely heard about another promising student who was off doing fieldwork in Samoa. Presiding over it all was Boas himself, the regal but warm father figure she had never quite had in Florida. “Of course, Zora is my daughter,” Hurston recalled Boas saying at a department party, with probably a fair bit of her own embellishment. “Just one of my missteps, that’s all.”

Hurston took to calling Boas “King” rather than Papa Franz in letters to friends and associates. “I am being trained for Anthropometry. . . . Boas is eager to have me start,” she wrote to Mrs. Meyer. She had been entrusted to Melville Herskovits for the anthropometry course, which was still a required subject in the field. Before long, she was standing on street corners, calipers in hand, inquiring whether passersby would mind having their measurements taken. Herskovits had even instructed her to assess gradations of skin tone by coding the lightness or darkness of the inner triceps, a question that predictably caused many subjects to turn and walk the other way.

While Hurston was still completing the requirements for her degree, Boas arranged for her to take on a field expedition back to Florida. She was to work on assembling, systematically, the kinds of stories with which she had regaled friends in Harlem—folktales and jokes, verbal quips and half-true lies. It was a source of tremendous pride that she had been asked and that Boas arranged a fellowship to cover the costs. In February 1927, she set off for the South, this time as a bona fide apprentice anthropologist—“poking and prying with a purpose,” as she would later describe it. It was the first time anyone had paid her to do something that came so naturally, to sweep up the stories that fell like wood shavings all over Joe Clarke’s porch, and it was heady beyond belief. She was bound for a place that was both intimately familiar and newly, magically strange.

At Barnard and in Harlem, people knew of Eatonville from Hurston’s tales and barbs, but plenty of people had already come across her section of Florida. Anyone who was paying attention had read the newspaper reports about a neighboring town, not quite twenty miles from her childhood home, called Ocoee.

On November 2, 1920, Election Day, a local man named Mose Norman had come to the polling place in Ocoee to cast his ballot in the presidential race. The contest offered a choice between two Ohioans—Senator Warren G. Harding and Governor James M. Cox—and it was the first presidential election in which women in every state had the right to vote. A massive voter registration drive aimed not only to bring women to the polls but also to increase participation by African Americans. In Florida a person like Norman was easily turned away. Across the state, white election officials conspired to challenge Black voters’ registration credentials, a common method of voter suppression. Norman protested but was chased off by a white crowd.

Word went out that Negroes were rioting. White reinforcements arrived from neighboring towns. Norman took refuge in a house owned by a man named July Perry, which was soon set upon by the growing mob. After shots were exchanged, white attackers worked their way street by street, ransacking houses and torching churches. Perry was dragged from a car and hanged from a telephone pole along the highway. Norman escaped, but other stragglers were pursued into the brambly woods and shot.

Every Black family that had not been killed was beaten, burned out, or forced to leave. The death toll was uncertain, since there were few people around who cared about identifying bodies or ensuring proper burials, but the figure perhaps ran into the dozens. “White children stood around and jeered the Negroes who were leaving,” wrote one eyewitness. “These children thought it a huge joke that some Negroes had been burned alive.” The five hundred or so survivors could be seen trudging along the highways, miles from town, like refugees from an undeclared war. The New York Times carried the news as a front-page story.

Ocoee would turn out to be one of the bloodiest and most unsparing anti-Black pogroms in American history. It ushered in a new wave of massacres that the newspapers routinely mislabeled as “riots”: murderous patrols by white citizens in nearby Orlando and Winter Garden; the storming of Black neighborhoods in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921; the racial cleansing of the town of Rosewood, Florida, in 1923; the destruction of Black businesses in Little Rock, Arkansas, four years later. With the addition of further lynchings and innumerable one-off beatings and indignities, it was the largest upsurge in organized anti-Black violence at any point since the end of slavery.

It would take Hurston a decade to write about Ocoee, in an unpublished essay unearthed only after her death. But she knew the world to which she was returning in 1927—alone and with only a vague plan for collecting ethnographic material, perhaps doing some writing in the morning and some anthropology in the afternoon, as she told Annie Nathan Meyer. As she made her way south, she kept correspondents abreast of her safety as well as her progress. Florida had not gotten any friendlier in her absence. She found poor whites to have “the harshest and most unlovely faces on earth,” staring out with “aggressive intolerance,” even though she reported no particular troubles along the way. “Flowers are gorgeous now, crackers not troubling me at all,” she wrote to one correspondent, using the term in common use for Florida’s rural white residents.

In the time she had been away, nearly half a million new inhabitants had come to the state. The Atlantic and Gulf coasts were booming with migrants from the North, mainly white, via a rail system that ran eastward from Chicago and southward from Boston, New York, and Philadelphia—the “Orange Blossom Special,” as a popular fiddle tune was called at the time. Still, Jim Crow authoritarianism drew sharp lines between the public lives of Blacks and whites. Not a single school was racially mixed before midcentury. A combination of the poll tax and the so-called white primary—in which political parties were treated as private clubs that could exclude African Americans and decide the election for southern Democrats well before polling day—kept Blacks from exercising the right to vote. Even the state’s beaches were strictly segregated.

By the 1920s in Florida, unlike in other southern states, Blacks and whites were close to parity in their shares of the population. As a result, the white community tended to see its own position as somehow under threat, the politically and socially dominant now recasting themselves as victims. Violence was often the preferred way of rectifying the perceived imbalance. Between 1890 and 1930, Florida had, per capita, more public lynchings than any other state in the country, almost exclusively of African Americans—twice the number in Mississippi and Georgia, three times that in Alabama. Yet before the mid 1930s, not a single person in the state was convicted of lynching. Unpunished mob violence such as the Ocoee massacre seemed to embolden terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, which witnessed a new upsurge in recruits.

Outside the towns and resorts that were growing along the coasts, Florida was the heart of darkness: a landscape of dense timberland and open scrub prairie, sparsely populated, where white sheriffs and mayors ran their jurisdictions like petty fiefdoms. The region’s major industries—cutting down virgin timber, boiling up turpentine from the endless pinewoods, pulling natural phosphate out of the ground for use in chemical processing and artificial fertilizers, and tending the burgeoning orange groves—demanded enormous amounts of human labor. Floridians had long understood that their jails and prisons were full of it.

Convicts had routinely been “leased” to local developers and industry leaders, in a form of labor bondage that amounted to a new kind of enslavement. Florida abolished convict leasing in 1923—one of the last states to do so—but the privatization of imprisonment in the service of big business continued. Chain gangs could be sent out to work on rural roads as a form of rehabilitation. Tenant farmers could be imprisoned for nonpayment of rent—a criminal offense under Florida law, not a civil one—and then forced into a private labor camp to work off the debt. Few of the state’s major industries could have functioned without this cheap, guaranteed, and captive labor source, one that consisted overwhelmingly of African-American men. “We used to own our slaves,” said one farmer as late as 1960. “Now we just rent them.”

Hurston knew of the brutal, mosquito-bitten reality of Florida’s interior. It was in fact exactly where she was headed. Her aim was to do some systematic collecting of folktales, sayings, stories, and other ethnographic material among Black communities in the state’s northern and central counties. Her financing had come from a foundation devoted to Negro culture, but she was traveling on Boas’s suggestion and under his aegis—which is why she decided to list him as a reference when she financed a used car for the journey. Boas was later surprised to be contacted, out of the blue, by a Jacksonville loan company. “You certainly ought to have written to me about this matter so that I may know why you want the money,” he wrote to her, the first hint of the exasperation that would wind through their correspondence over the years. But it all became clear when she informed him that it would be impossible to get to the best field sites without an automobile.

By March 1927 she was tooling through the back roads, headed farther south into the wrinkled landscape, her Nash coupe—“Sassy Susie,” as she had named it—kicking up a gray cloud behind her. She hit Palatka, on the muddy St. Johns River upstream from Jacksonville; Sanford, where many of the Ocoee refugees had fled; Mulberry, on the edge of the central lake district; Loughman, with its labor camp workers sweating in the dense underbrush; as well as Eatonville—John Hurston’s daughter now back home and made good.

The landscape seemed designed, in one way or another, to sting, stick, bite, or scratch. Sunlight filtered through spiky palms. Great stands of cypress stood up on their octopus legs out of the swampy muck. Poinciana trees bloomed into burning bushes, while swarms of gnats and mosquitoes hung stationary in the breezeless air. Public bathrooms were restricted to whites, as were most motels and restaurants, which was why Hurston, like any African-American traveler of the period, headed straight to the Black side of town at the end of each day’s travels, the only place likely to offer her a bed and a meal. Just in case things went wrong, she had a chrome-plated pistol at hand.

It took her awhile to figure out how to be a working anthropologist. “Pardon me, but do you know any folk tales or songs?” she recalled asking in what she called her “carefully accented Barnardese.”

Like Margaret Mead in Samoa, Hurston even brought along a handful of printed stationery—hers with the Barnard College seal—which she used as an incongruous vehicle for dispatching news from the field. She had grown up hearing stories at Joe Clarke’s store, but that was in a community she knew, with family and friends. This was different. You couldn’t just roll into town in a sputtering car, sidle up to a bunch of strangers, and ask them to tell you everything they knew on the spot. It took time to understand people, to demonstrate your good faith and get them to trust you.

Soon she shipped back to Boas a typescript, the first draft of what she hoped would be a detailed study of the folk life of Florida. If she had the chance to do more collecting, she said, she might extend it to all the Gulf states. She had even more material in pencil and hoped to be able to type it up soon. She had been trained in anthropology as the art of salvage, and she now understood what that meant. The first thing people would often say to her was that they had forgotten all the “old stuff.” With enough conversation and prompting, they might open up. But it was all disappearing fast. Their “negroness” was being “rubbed off by close contact with the white culture,” she told Boas. To make sure she got it all down, she took notes in phonetic spelling, with the as de and that as dat, in a way that would have scandalized some of her old professors at Howard.

Hurston was gradually giving a scientific gloss to a gut feeling, something that had always bothered her about the way the older generation of Black intellectuals regarded people like her. What if all the stories and the stomping, the porch banter and the ax-swinging work songs, were placed alongside Samoan tattooing or Kwakiutl wood carving as activities that constituted their own system of rules, rituals, and routines? A fully formed yet unappreciated recipe for living as a human being seemed to be lurking in the dense pinelands and lakeshores of northern and central Florida—something as yet uncataloged, as Boas or Benedict might have put it in their lectures. To Hurston, the ways of life that white people made into frolicking blackface, and that Black “race leaders,” as she called them, would rather not discuss, were coming to look more and more like the very thing she had heard Boas’s other students talk about: a culture, with an aesthetic sensibility and moral order all its own.

Over the next few months, Hurston remained in Florida and then, in the summer, gradually made her way to New York, traveling for part of the journey in Sassy Susie with Langston Hughes, who had been making his first visit to the South. On her outbound trip, she had acquired a husband, Herbert Sheen, a University of Chicago medical student whom she had married hastily. But now he was noticeably absent. She told Hughes the next spring that she and Sheen were ready to call it quits.

She had rather little to show for her time away. She eventually wrote up a slave narrative that she supposedly collected in Mobile, Alabama, and published it in the Journal of Negro History. Much of her text, however, turned out to be plagiarized from an older published source, a fact that escaped academic reviewers at the time. She consulted Boas about what to do with the other materials she had amassed, but a meeting with him reduced her to tears. He had urged her to be more systematic, to pay particular attention to the transmission of proverbs, myths, and musical forms from European planters to African slaves, and she had failed to follow that advice. Her field notes and interview data, he told her, contained little that wasn’t already known. The only way of rescuing the six months she had spent in the field was to go back and do more.

After a short period in New York, she headed south again. This time she traveled under the aegis of a patron, Charlotte Osgood Mason—or “Godmother,” as she insisted on being called. Mason lived in a 12-room Park Avenue apartment filled with antiques, bone china, and African art, the latest issues of Harlem Renaissance publications fanned conspicuously on the side tables.

Like several other white philanthropists of the era, Mason believed that Black intellectuals had a special facility for tapping into humans’ most ancient and authentic practices and beliefs. She was an early supporter of Alain Locke and, through him, became benefactor to a wide circle of Harlem writers and artists. In return, she demanded intense loyalty, even obedience. She agreed to take on Hurston as a formal employee, with a $200 monthly salary. It gave Hurston a financial stability she had never known but obligated her in new ways. She could continue her collecting while also pursuing some of the literary work that had languished while she was in the field. Any material Hurston collected, however, would belong to Mason.

Boas had been urging Hurston to write a real ethnography, but as weeks turned to months, her scientific work amounted to little more than piling up reams of notes, ideas for books, and even film reels, since Mason had furnished her with a camera to record folk life as she found it. In 1928 and 1929, Hurston was back in Eatonville and Maitland, then in turpentine camps and lumberyards, later a swing through Alabama and an autumn and winter in New Orleans, then another cold season in Florida, later still an excursion to the Bahamas. Her work wasn’t so much about capturing a dying culture as trying to understand the here-and-now of a ferocious, angular way of being. Don’t tell Godmother, she wrote back to Hughes, but “Negro folk-lore is still in the making.”

Not until the spring of 1930 was she again in the New York area for any length of time, promising Boas that she was working hard on at last producing something of value out of the fieldwork that had occupied her, off and on, for three years. Her luggage was stuffed full with notes and tales, stories and character sketches, from more than a hundred different people: phosphate miners, domestics, laborers, boys and girls, Bahamian plantation owners, shopkeepers, ex-slaves, sawmill hands, housewives, railroad workers, restaurant keepers, laundresses, preachers, bootleggers, along with a Tuskegee graduate, a “barber when free,” and a “bum and roustabout,” as Hurston noted. But her reports were usually disappointing. “At last I come up for air,” she wrote to Boas that summer. “It’s been very hard to get the material in any shape at all.”

Hurston came back to New York with “my heart beneath my knees and my knees in some lonesome valley,” as she recalled. She struggled to make sense of the material she had gathered and to transform it into something other than a random assortment of anecdotes.

She worried that she was a disappointment to Boas as well as to her benefactor. Boas had wanted her research to be systematized somehow, to reflect broader theorizing about how stories were transmitted from place to place or how folk symbols changed over time, from Africa to the Americas. Mason had wanted unadulterated, primitive art, which she had vaguely intended to use in some of her own work as a would-be folklorist.

Hurston continued to correspond with Boas, providing periodic updates on her note-taking and academic writing. Her relationship with Mason gradually soured. The stock market crash made Mason less generous with her patronage, which eventually dwindled to nothing. Hurston once more found herself looking for means of support: an application for a Guggenheim Fellowship (denied), a proposed chicken-based catering business for wealthy New Yorkers (never launched), a stint producing musical revues (barely covering her costs). Even her relationship with Langston Hughes, which might have yielded the most dynamic collaboration of the Harlem Renaissance, faded, the casualty of a failed effort to produce a play drawn from Florida folklore. But now shed of Mason, Hurston was free to pursue fiction even as she was chasing down ethnological facts. “I have kicked loose from the Park Avenue dragon and still I am alive!” she wrote to Ruth Benedict. “I have found my way again.”

While living in Florida, she had sketched out a story line loosely based on her own experience as the daughter of a troubled southern preacher. She wrote and rewrote a text, then borrowed $1.83 in postage to send the typescript to a publisher, Bertram Lippincott of Philadelphia. Sometime later a telegram arrived announcing the novel’s acceptance—on the very day, it turned out, that she received an eviction notice. Still, the news came like a sun shower on a muggy Gulf Coast day or, as Hurston later described it, as more thrilling than finding your first pubic hair. The novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, appeared in 1934. It was hailed as a fine “Negro novel,” with good reviews and praise for Hurston’s emerging role in the company of Hughes, West, and other Black writers.

Lippincott’s advance against royalties was less than half of what another first-time author, Mead, had received six years earlier. It was hardly enough to pay rent, much less to found a career. Hurston would have to find a line of work to sustain her between book contracts and one-off writing projects. In January 1935 she enrolled as a doctoral student at Columbia. That path had previously been blocked by the overbearing Mason, who had insisted that an advanced degree would be a waste of time and energy. Boas signed on as her mentor. The Julius Rosenwald Fund, a philanthropic group that supported Black artists and scholars, promised a fellowship to cover her studies on “the special cultural gifts of the Negroes.” “I might want to teach some day and I want the discipline for thoroughness,” she told Boas.

Later that year Hurston managed to wrench into some kind of order the sheaf of notes, transcripts, and stories she had hauled back and forth between New York, New Orleans, Eatonville, and points in between, her mind lurching from “corn pone and mustard greens” to “rubbing a paragraph with a soft cloth,” as she said. “Thanks and thanks for fixing up the MS so well,” she wrote to Benedict, who had offered comments and editorial suggestions. Lippincott published it in the autumn as Mules and Men. After some pleading by Hurston—“I am full of tremors” in even asking, she said—Boas agreed to write a foreword. He praised Hurston’s book as the first attempt anyone had made to understand the “true inner life of the Negro.”

Folklorists had previously thought they were getting at the hidden essence of a community, but what they often ended up with, Hurston believed, was offhand pleasantries and made-up tales. It was little more than lint-rolling passed off as science. Mules and Men was the first serious effort to send a reader deep inside southern Black towns and work camps—not as an observer but as a kind of participant, as Hurston had been.

Folklore was “the boiled-down juice of human living,” she would later say, and on page after page, she joined in on the boiling-down. She abandoned grammatical detachment and used the first person to tell of meeting people, talking to them, even narrowly escaping a knife fight, the dust roiling behind her car as she sped out of town.

Hurston wrote about Eatonville and Loughman, with their loggers and turpentine boilers, bootleggers and juke crowds, in the past tense—ran, hollered, fell, cut. She was offering readers a creative, interpreted record of things she had witnessed and heard about, with her informants situated in time and space. She communicated her science exactly the way she had performed it: as a conversation in which she, the observing intelligence, was also part of the action. She was making data, not just gleaning it.

Her prose didn’t just repeat other people’s stories—about romantic courtships and the origins of race, about the hidden lives of animals or the interminable conflicts between Baptists and Methodists. It actually took you straight into a sweaty room, with flies buzzing and liquor being passed around the circle. It was a grand unspooling, the stories arranged not so much by chronology or theme as by their own poetic imagery. A single word from one story might suggest a new one on an entirely different theme, the way one storyteller would pick up where another had left off. “Ah know another man wid a daughter,” someone would say, or “I know about a letter too,” and you’d be away on another tale, one flowing into the next.

Hurston didn’t claim to speak for all Black people or to have captured some deep, essential Blackness. But she knew that no one on Joe Clarke’s porch thought of himself as speaking a bastardized version of English. None of those people imagined themselves to be in the dim twilight of African greatness. In Mules and Men she had tried to show, in plangent prose and revved-up storytelling, that there was a distinct there to be studied in the swampy southeastern landscape she knew from childhood—not a holdover from Africa, or a social blight to be eliminated, or a corrupted version of whiteness in need of correction, but something vibrantly, chaotically, brilliantly alive.