John James Audubon, dead for 172 years, has been in the news again. Disturbing facts known to his biographers—that, for example, when he kept a store in Henderson, Kentucky, he enslaved people—have gained new currency, although the National Audubon Society has, for now, held on to its name. For many, Audubon has become synonymous with an activity—call it science, ornithology, natural history, birding, love of the outdoors—that has, for the longest time, excluded people of color.

Such reconsiderations are timely and important. In the foreword to Audubon at Sea, a new anthology of Audubon’s works about aquatic birds that I coedited, the artist and activist Subhankar Banerjee describes the reconsideration of Audubon’s failings as “part of a vigorous and necessary debate about a shared, sustainable future.” Those continuing to argue that the National Audubon Society rebrand itself—the way local chapters and a regional association of naturalists have already announced they will—do so in the hope that such a gesture would spur greater diversity among nature enthusiasts. Given his seemingly no-holds-barred killings of birds, some would argue that Audubon has always been an awkward fit for a conservation society anyway. That said, the founders of the Audubon Society and its local chapters never sought to honor the man but the fragile beauty of the birds he depicted.

I first encountered Audubon’s work about 30 years ago, becoming hooked instantly on prints that showed birds as I had never seen them before, so unlike the static profile outlines in my father’s well-thumbed handbooks. To me, many of Audubon’s plates were self-consciously violent pictures, made by a man who knew violence himself and had participated in it: sharp, yellow beaks open in agony, bony talons raised in attack or defense, eyes widened in horror at being discovered, shattered eggs dripping yolk, a broad wing stretched in the panic of getting away, at least for now, from what will happen anyway sooner or later, some unheralded, unspectacular death deep in a thicket, a pile of feathers on a rock, blood oozing from an unseen wound, once-vibrant colors fading rapidly as the light fails and the body stiffens. Audubon’s birds sing and scream, kill and get killed, eat and defecate. One of his best-known compositions, of the majestic wild turkey, displays (unnoticed even by those who study his work) a pile of poop in the lower left corner.

Since that first encounter with Audubon’s art, I have written about him in a book titled The Poetics of Natural History (recently republished by Rutgers University Press), edited Audubon’s writings for the Library of America, led two NEH summer institutes for schoolteachers on Audubon’s work at Indiana University’s Lilly Library, prepared a digital exhibition of the 50 most important plates from The Birds of America, and coedited Audubon at Sea. I know the highs and the lows of Audubon’s work, his successes as well as his failures. My hope is that Audubon’s contaminated reputation might not obscure how far outside the established norms his work was even in his own day. His contemporaries accused him of being an amateur, of falsifying or stealing his evidence, of committing, knowingly or not, grievous errors—charges that still resonate today, with scholars devoting entire articles to ferreting out his missteps. Had the equivalent of the Audubon Society existed in Audubon’s own time, he wouldn’t have been a member.

Reminding ourselves that Audubon has always been problematic doesn’t let him off the hook. It provides some context, though, for current discussions and allows us to consider what his work might still have to tell us, the way he once spoke to me, violently, passionately, intensely, when I was still an undergraduate at a German university and had not yet seen an American bird in the flesh. Audubon simply won’t go away: The 435 life-sized engravings in The Birds of America (1827–38), made after Audubon’s original watercolors by the London printer Robert Havell Jr., remain part of our shared cultural heritage, one of the most influential works of scientific art ever produced. To me, however, it’s an open question whether the salutary and even radical parts of his legacy have ever been fully understood. Do they justify his racism? Certainly not. Yet when my collaborator Richard King and I were putting the finishing touches on Audubon at Sea, I was reminded again how his art and his writing directly challenge some of the parameters of nature observation we still take for granted today. Thinking about Audubon, I often find myself returning to a brilliant essay by the Nigerian American writer Teju Cole about Caravaggio, another great artist who wasn’t an exemplary human being. We keep going back to Caravaggio, wrote Cole, not to discover “how good people are” and “not because of how good he was.” Instead, we seek him out (and, I would argue, Audubon, too) for “a certain kind of otherwise unbearable knowledge” about our vulnerable world and our difficult place in it.

There is no question that Audubon loved birds, even as he killed them by the barrelful. Born in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) as the illegitimate son of a captain and slave trader, an immigrant non-native speaker of English who never shed his accent and fought a lifelong battle with English grammar and spelling, he found the strangeness of birds infinitely appealing. There is a chilling poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “The Birds of Killingworth” (1863), in which a group of patriotic citizens engage in a crazy effort to eliminate the local bird population, not just because they ravage their fields but because so many of them are birds of passage, foreigners, visitors from far away, “speaking some unknown language strange and sweet.” Audubon’s plates and the essays he wrote to accompany them shimmer with his admiration for birds’ otherworldly beauty, holding them in a tender embrace that leaves the purposes of mere scientific description behind. A useful way to think of his art and writings is to treat them the way he told us we should when he called his essays Ornithological Biography—as a vast biographical effort, on the order of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), with the important difference that the subjects of his attention are most excellent birds, not excellent humans. Audubon stares at his birds the way devoted biographers stare at their subjects—trembling with a desire to make them their own, if only on the page, through words or paint. But, as he finds out time and again, his own weirdness is no match for theirs—Audubon’s birds constantly elude him.

As Elizabeth Hardwick has pointed out, biography is a predatory enterprise, a surreptitious looting of the pharaoh’s tomb or (in Audubon’s case) of a bird’s habitat. And it’s an exercise that mostly goes unpunished. Audubon’s biography “Barn Owl” starts with the surprising observation that, although everyone seems to have seen this beautiful bird, no one knows much about it, even though these owls are abundant, especially in the South, and live where humans live, too, in the chimneys and garrets of houses or near abandoned fields, where they find an abundant supply of mice. In his biography of the barn owl, (which he radically shortened for the later, octavo-sized version of The Birds of America), Audubon ditches the structure he adopts in other entries and recycles entire pages from his journal relating personal encounters with these birds. For example, when visiting his friend and collaborator John Bachman in Charleston, someone told him about a pair of owls nesting in the attic of an old “sugar-house” (a sugar refinery). Impressed with the fierceness of the three young, richly cream-colored owl babies he finds there, Audubon, over the following weeks, returns a couple of times and soon begins messing with them, measuring them, even touching their feathers (they were, he notes, “full of blood,” as if ready to burst). One of the young owls dies; the other two he removes. “I took them home,” writes Audubon. You can imagine what happened to them.

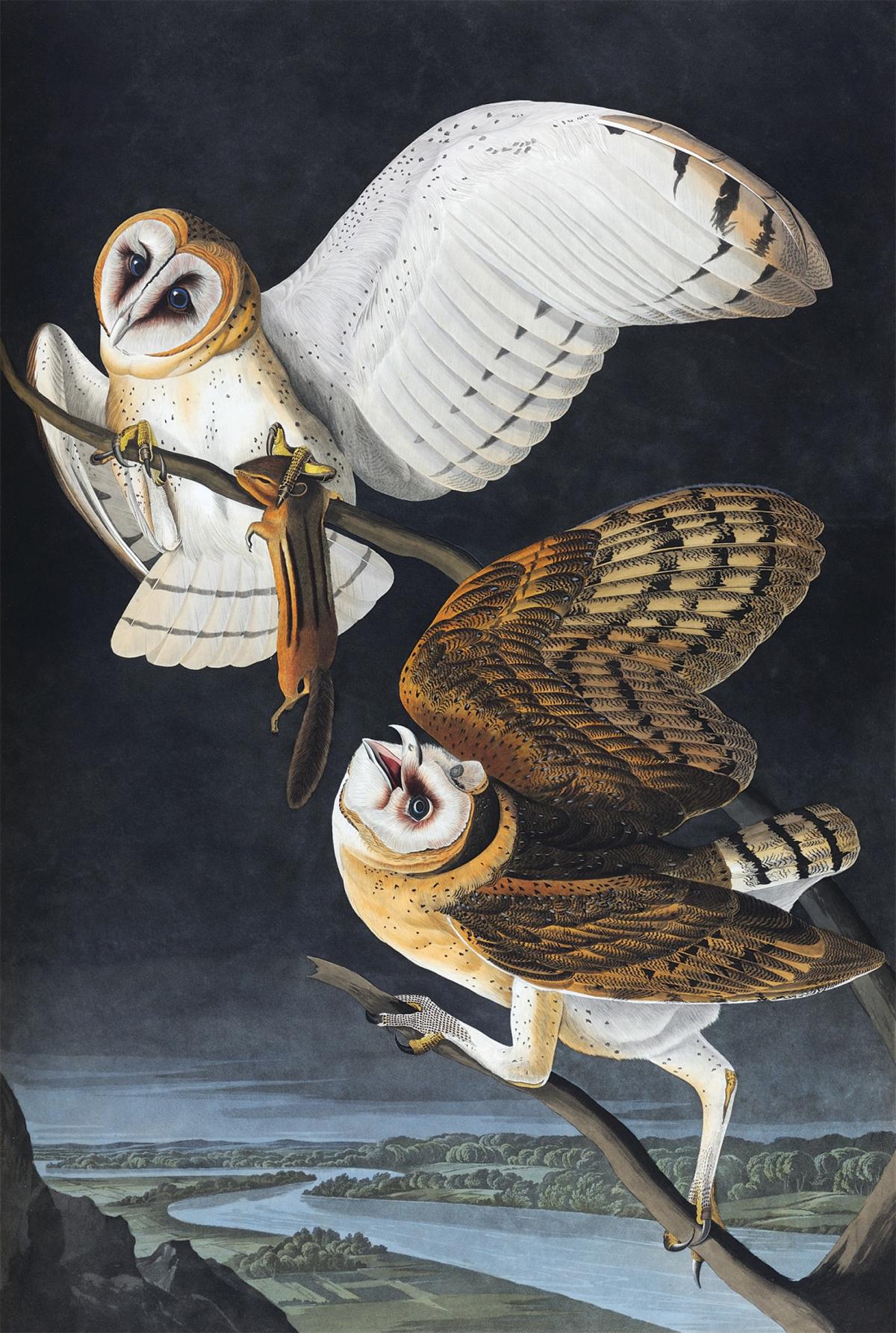

Whatever closeness Audubon achieved with his sugar house owl babies, there’s not a trace of that to be found in the matching plate. It’s one of three night scenes included in The Birds of America, and Audubon makes full use of that unusual setting. We see two owls, the larger female on the top branch, a male below, their heads cocked, their eyes focused on a lifeless chipmunk dangling from the talons of the female. The smaller male is straining toward the dead rodent as if it were a piece of candy.

If this is a playful scene, it’s not the human viewer’s sense of fun. On the one hand, the birds look solid, like two Dutch burghers in fur-lined finery, though their heart-shaped, mask-like faces work against that comparison. The white underside of the female’s wing and her white belly dazzle, enhanced by the dark background. Audubon’s printer, Havell, added a meandering river with woodland and fields on either side, and a fragment of a mountain on the left. Levitating high above the landscape, clutching bare branches that look like they could snap any minute, the birds seem comfortable where humans couldn’t exist. They perform a spectral ballet of sorts, raising their wings as if in sync, giving us both interior and exterior views—a composite rendering of a barn owl’s morphological features. Audubon gives us a cool, stylish fantasy that flaunts its artificiality, just anthropomorphic enough to remind us that these birds are anything but human. This is a scene Audubon never saw. The dangling chipmunk, too, came entirely from his imagination: “I have placed a ground squirrel under the feet of one of them, as being an animal on which the species is likely to feed.” As if to justify the addition, Audubon, in the essay’s original version, appended a little essay on the chipmunk. “We have no small quadruped more interesting than this.” (A barn owl would heartily agree.) Audubon praises the chipmunk’s beautiful markings, its grace and vivacity, stating that, among quadrupeds, it is what the wren is among birds: small, lively, and a pleasure to behold. “I think I see him as he runs before me with the speed of thought, his tail quite erect, his chops distended with the produce of the woods, until he reaches the entrance of his retreat. Now he stands upright, clatters his little chops, and as I move onwards a single step, he disappears in a moment.”

Audubon’s bird biographies are full of animals that vanish. But in this imagined scene he won’t let the chipmunk get away, as if he himself were a hungry owl looking for dinner. A case of the biographer identifying too much with his subject? Before we have even realized it, this attempted vignette of a cute squirrel has turned into a tale of horror involving a human brandishing an axe: “Stone after stone I have removed from the fence, but in vain, for beneath the whole the cunning creature has formed its deep and circuitous burrow. With my hatchet I cut the tangled roots, and as I follow the animal into its innermost recesses, I hear its angry voice. I am indeed within a few inches of his last retreat, and now I see his large dark protruded eye.” But the little guy gets away: “At this moment out he rushes with such speed that it would be vain to follow him. . . . I willingly leave him unmolested in that to which he has now betaken himself.” Audubon is, after all, not a barn owl. The reader might be forgiven for thinking that while such compassion works in the chipmunk’s favor, it comes too late for the young owls in the sugar house or, for that matter, the owls in the plate. Audubon always painted from freshly killed specimens, though in this case the owls were even deader than dead, mailed to him from Philadelphia by the naturalist Richard Harlan.

Birds are, finds Audubon, stranger than strange. His biographical tools—words and paint—falter when he wants to capture what he sees, yielding to make-believe (the barn owl ballet) or chattiness (the story about the cute chipmunk). Some of his descriptions are pointlessly repetitive. Consider his biography of the ibis. Spellbound by the bird’s sheer glossiness, Audubon has to say “glossy” all over again: “The upper part and sides of the head are dark glossy, with purplish reflections. . . . Excepting the anterior edge of the wing, and the anterior scapulars [the small feathers on the bird’s shoulder], which are deep glossy brownish-red, the upper parts are splendent dark green, glossed with purple; the primaries black, shaded with green; the tail glossy with purplish reflections.” (The italics are mine.) The repetitions emphasize the gulf that separates the bird from the observer, the bird’s reality from the language its biographer uses to capture his subject. Abundant today, the glossy ibis, in Audubon’s time, was still “exceedingly rare,” which was a factor in his excitement.

As if he wanted to make fun of his own efforts, Audubon has the world of human ambition enter his plate right behind that wonderfully glossy bird, and that world is anything but glossy. We can just barely make out a farmhouse and a few fence posts: the faded, boring, and washed-out signs of human habitation, eclipsed by the simple but powerful drama of that multihued bird about to dip its elegant beak into the water. These backgrounds were often made not by Audubon himself but—at his direction—by the assistants who traveled with him or by his printer, Havell. A more elaborate example is the view of John Bachman’s Charleston in the background of the plate showing the long-billed curlew, another version of the “bird-dips-bill-in-water” theme, this time in a more civilized setting. We see from a distance the city of Charleston, not as a human would see it but as a bird would, from the vantage point of the “Bird Banks” in Charleston Harbor. Audubon liked such visual inversions. For him, they were more than idle play.

In his biography of the long-billed curlew, Audubon recreates a trip he and his men undertook to Cole’s Island southwest of Charleston in November 1831, where they, as the sun was setting, watched thousands of long-billed curlews pouring in, getting ready to spend the night. The birds were “by no means shy,” reacting to the presence of the hunters only by moving, soundlessly, to the “extreme margins” of the island. As the human intruders sit down for their improvised dinner, fried fish and oysters, prepared by Audubon himself, they discover they forgot to bring salt. Not a problem for the perennially inventive Audubon, who substitutes gunpowder for it. What an image—Audubon’s hunters huddled around a fire, devouring their meal with fingers stained by the “villanous saltpetre”! Everyone slept soundly afterward.

The shootings commence the next day. As Audubon reports, some of the shocked curlews take a good long while to die (“so long as life remains in them, they skulk off among the thickest plants, remaining perfectly silent”). The gunpowder that a few hours ago flavored the dinner of the hunters now kills the birds they pursue. In the original watercolor, by some odd coincidence, the sculptural beauty of the curlews is offset by some spilled paint on the left, a reminder of the messy killings that preceded the making of the picture. Audubon’s best works transcend the destructive logic that inspired them, mocking the arrogant desire to appropriate what we cannot truly possess. His birds, fantastical, silent, unknowable, frozen in time, warn us not to assume what is beyond our understanding.

Audubon was no fool. In his decades of ornithological fieldwork, he noticed that some of the most numerous American bird species (the Carolina parakeet, now extinct, is a good example) were rapidly decreasing, that their habitats were shrinking and food sources declining. In our own time, that dismal process has only accelerated: During the last 50 years, the number of birds in the United States and Canada alone has fallen by 29 percent. We might remind ourselves that the human world depicted in Audubon’s art was a white, or mostly white, one. In Audubon’s curlew essay, we never learn if the servants who procured the fish (and who were, presumably, Black) got their share of the dinner Audubon had so creatively prepared. And while the Charleston residents who accompanied Audubon to the old sugar house with its nesting barn owls are identified by name, “the Negro man who kept the house” is not. In a bizarre way, though, the conspicuous whiteness of Audubon’s environment makes his critique of the hunters’ depredations even more stinging.

In his biography of the canvasback—called canard cheval (“horse duck”) in New Orleans, a name emphasizing their usefulness—Audubon is almost comically intense about the birds’ culinary and monetary worth: $2 (about $50 today) gets you a pair. Audubon supplements his biography with detailed anatomical measurements, another way in which to turn a living, breathing thing into an inanimate object, a jumble of body parts: “The trachea, when moderately extended, measures 10 inches in length. . . . Its diameter at the upper part is 4½ twelfths, it gradually contracts to 3½ twelfths, enlarges to 4½ twelfths, and at the distance of 7¼ inches from the upper extremity, forms a dilatation about an inch in length.”

But the finished plate, in which Havell transformed the rough outline of a city into a miniature view of Baltimore, tells a different story. Here we don’t see tracheas or stomachs but living, breathing, swimming birds, a male and female positioned on the rocky ledges on the left and right, a male in the middle, drifting tranquilly in the wavy water. And just as we see the birds, the birds see us. Humans are both before and behind them—represented by those who view the plate and those who live in it (the residents of Baltimore). Again, Audubon substitutes for the human point of view the perspective of birds—birds that want nothing more than to be allowed to get on with the business of being birds. Audubon’s canvasbacks are the stately gatekeepers of a world that they know was never ours to share with them but always theirs to share with us—reminding the viewer of the enduring ecological edge of Audubon’s art.