Beneath the surface of the Brownlee Reservoir in eastern Oregon lies the town of Robinette, once a thriving community, now covered by 100 feet of water.

In its heyday, Robinette was home to a train depot, a hotel, a one-room schoolhouse, and a distinctive tavern shaped like a military Quonset hut. The town flourished beside the Snake River, where fruit trees hung heavy with peaches, apricots, and walnuts.

In 1957, the town’s residents left their homes forever to make way for the construction of the Brownlee Dam, which submerged their community beneath the reservoir.

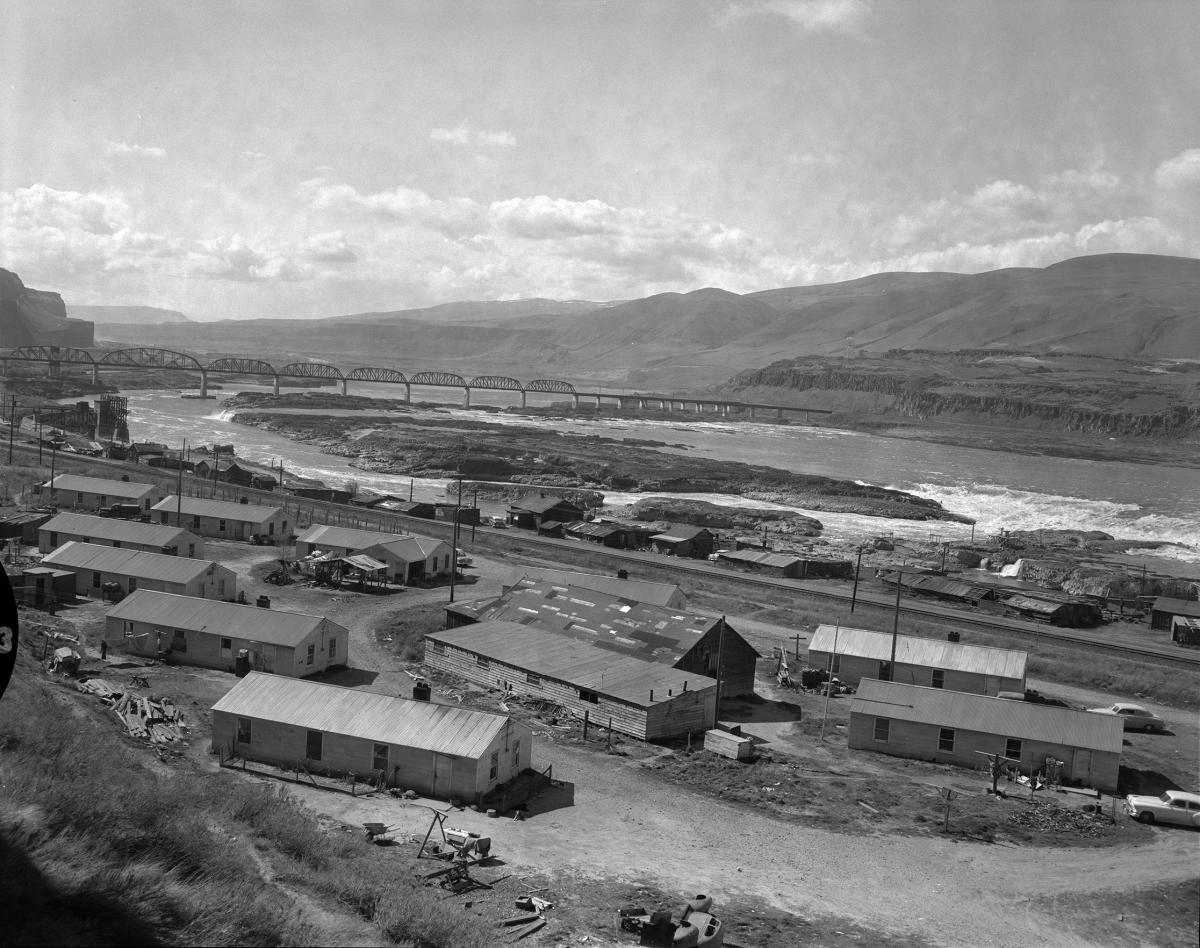

A similar fate befell Detroit, a town on the banks of the North Santiam River in western Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Described by the local Mill City Enterprise as a “brawling logging town,” Detroit was known for Whitey’s Café, a boarding house, and the Cedars Lounge and Tavern. A suspension bridge swung across the North Santiam. Big pines surrounded the town’s white clapboard post office, which resembled something from a stage set.

When the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began constructing the Detroit Dam in 1949, the agency relocated Detroit’s residents, along with 60 buildings (35 homes and 25 businesses), to higher ground. Completed in 1953, the dam created Detroit Lake, flooding the original townsite.

These towns were not randomly submerged. Their disappearance was part of a broader narrative about communities in the American West displaced for—depending on location—hydroelectric power, irrigation, flood control, and a twentieth-century idea of progress. This trend began in the 1920s, accelerated through the go-go years post-World War II, and continued through the Cold War era. It lasted until the 1970s.

Bob Reinhardt, an associate professor in the department of history and the School of the Environment at Boise State University, estimates that scores of towns in the western United States, hundreds across the country, and thousands globally have experienced fates similar to Robinette and Detroit. His research, beginning in the West, aims to preserve the histories of these lost places and prevent them from fading “out of memory and into myth,” he said. He is assessing the cultural and personal value of these communities—exploring the reasons people were willing to leave them and the ways they memorialized them.

Despite the number of towns in this country affected by hydroelectric projects, scholarship on the subject remains fragmented and limited. “We know more about the loss and relocation of communities in the interest of economic projects in China and in some African countries than we do in the U.S.,” Reinhardt said.

His multimedia public history project, the Atlas of Drowned Towns, tries to remedy that. The ever-evolving site is a first-of-its-kind compilation of the histories of these once vibrant American places.

The National Endowment for the Humanities awarded Reinhardt a grant to support the early stages of his work. Subsequently, he received a grant from the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University and, in 2022, a five-year, nearly $1 million grant from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to research flooded towns in Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

While hydroelectric and other water management projects affected communities across the United States, most projects involving significant federal investment were in the West. This was due to the region’s water scarcity, its arid climate, a rapidly growing population, and the presence of major river systems.

The largest number of projects took place during a time Reinhardt called “the Cold War’s context of consensus.” For the most part, public objection to the flooding of communities was mild. Dams generated energy for the aluminum industry, which, in turn, supported the aerospace industry. “And no one wanted to stand in the way of that,” he said. In addition, many displaced citizens saw relocation—supported by government reparations—as a chance to improve their lives.

Taking Detroit as one example, a 1952 headline in the Mill City Enterprise proclaimed, “Old Detroit Is Dead, Long Live New Detroit!” During the same period, the Oregonian interviewed Mrs. Joe Leis, who expressed impatience with residents who complained about the government and relocation. “The new town will be much more attractive than the old one,” she said. “Up there [at the new townsite] we will all own our own lots, and I expect it will be nicely landscaped. Ours will be on the waterfront.”

Still, amid this forward momentum and optimism, some mourned—a complicated sentiment Reinhardt is eager to investigate.

“Each one of these dams displaced somebody, even if it was just a few peach orchards,” he said. “When a family planted fruit trees, that was a sign that they planned to stay in a place for a long time.” Records include poignant stories of residents watching crews uproot their orchards. Trees and buildings, if left in place, could later cause problems when they washed downriver, so in many cases workmen removed them or burned them.

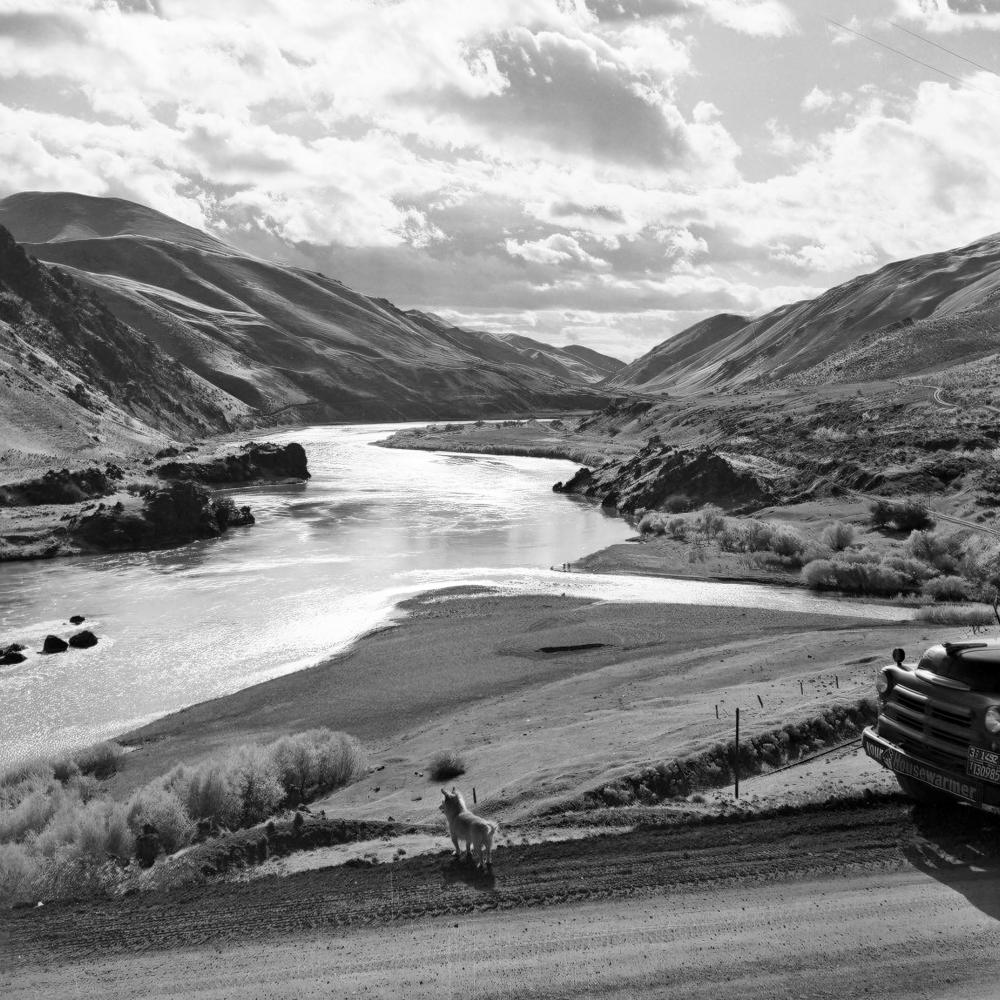

Others grieved, and still grieve, places like Celilo Village, 100 miles east of Portland, Oregon. The village was one of the oldest continuously inhabited sites in North America and a key location for trade and gathering among Indigenous tribes, including the Umatilla, Yakama, Nez Perce, and Warm Springs. Its flooding in 1957 for the construction of the Dalles Dam on the Columbia River (to slow water flow, making the river navigable for barges) included the loss of Celilo Falls, a massive series of cascades where tribes had fished for centuries. Residents lucky to witness it recall fishermen suspended with nets over the roiling water on thin wooden platforms. Submerging the falls erased livelihood, culture, and tradition. Tribes received some reparations, but the compensation in the face of such profound loss remains the subject of debate to this day.

By the 1970s, hydroelectric projects slowed. The Carter administration had other priorities, and projects began to face pushback from environmental groups that had become more powerful and politically savvy than in earlier decades.

Public outreach is central to Reinhardt’s work. In 2023, more than 100 residents attended a history-gathering “jamboree” in “new” Detroit, Oregon—the first stop on what Reinhardt called an indefinite tour. He and a team of volunteers digitized more than 400 photos, documents, and other materials.

They recorded a dozen oral histories, preserving invaluable first-person accounts from residents who lived in the town in the 1950s and earlier. One contributed a unique artifact: a commemorative plaque for the dedication of the Detroit Dam, complete with a button that ceremoniously “started” the dam’s operations. Another, Harold Baughn, recalled his boyhood, learning to swim in the North Santiam and playing on Detroit’s railroad turntable, a rotating platform that trains used to change direction or tracks. Baughn insisted that, some 70 years later, when the water level in Detroit Lake is low, he can still see the indentation where the turntable sat.

Marsha Weisiger, a professor of history and environmental studies at the University of Oregon, said Reinhardt’s community outreach invites residents to collaborate, “rendering tangible the stories their families have handed down. Storytelling is the strongest impulse we have as humans to relay history.”

The inclusion of Indigenous communities in the drowned towns research is significant, she added. With Celilo Falls, the Atlas of Drowned Towns includes the Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona, which flooded sacred sites of the Diné (Navajo), Hopi, Nuwuvi (Southern Paiute), and Ute.

“We speak abstractly about these hydroelectric developments. But the Atlas of Drowned Towns is helping to bring to the fore the communities and families who feel they were dismissed,” Weisiger said.

The next jamboree will take place in Sweet Home, Oregon, in 2025, focusing on two later dams on the South Santiam River: the Green Peter Dam (1967) and the Foster Dam (1968). Each displaced several homes and communities.

While Reinhardt is a historian, his study of flooded towns is relevant in the present. Climate change and shifting populations are likely to bring about even more places in transition, he said. “It would be good if we, as a society, could find respectful ways to mitigate the emotional and physical toll that comes with community displacement. Federal agencies can hopefully learn something about interacting with communities affected by these kinds of actions.”

Reinhardt’s work is helping the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers inventory the historical resources it manages and reconnect with communities, said Molly Casperson, district archaeologist for the Corps’ Portland district. “It provides Corps decision makers with a rare opportunity to consider how historic federal management actions influence how communities perceive themselves, and how this shapes perceptions of the Corps.”

The Atlas of Drowned Towns will continue to catalog watersheds in the West, with plans to expand throughout North America and beyond.

“I think these places and this project can help us understand something about resilience,” Reinhardt said. “Resilience is often equated with resistance. I think that’s a narrow vision. It can also be equated with persistence and the insistence of memory.”