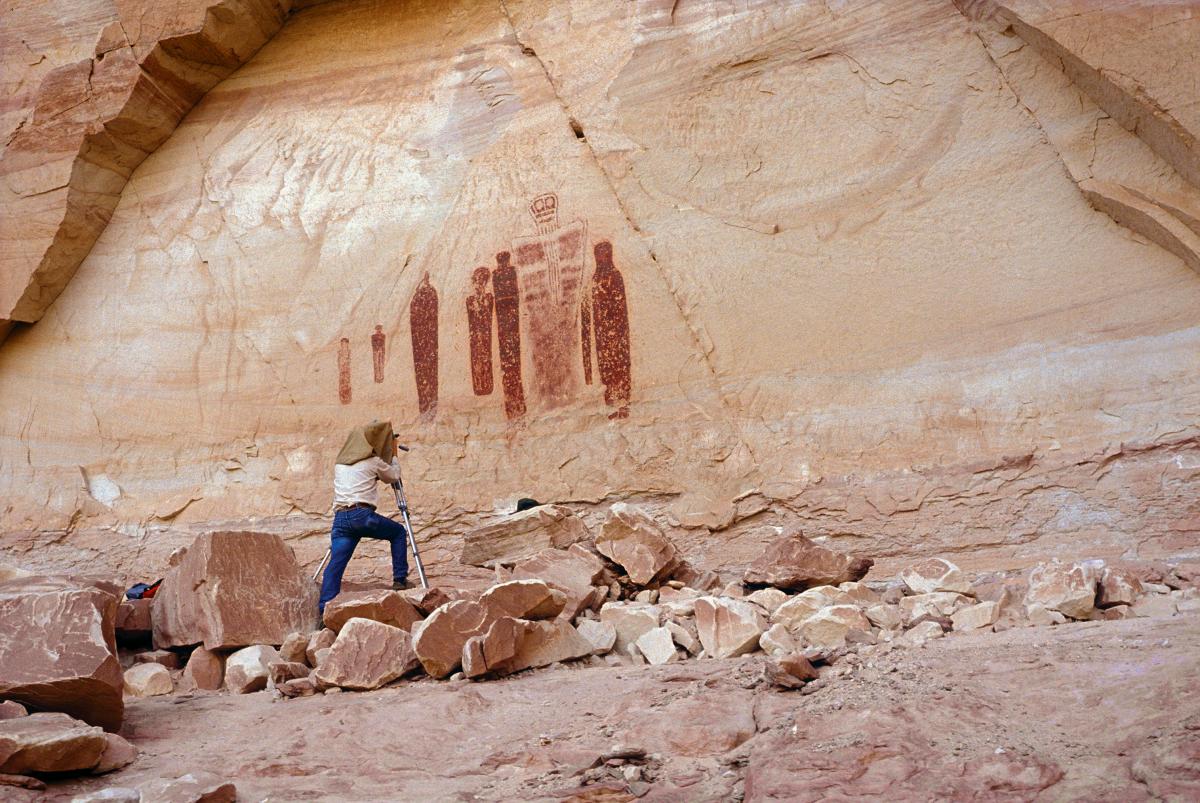

Of the thousands of Native American rock art panels in the Southwest, none are older than the Barrier Canyon pictographs found throughout the Colorado Plateau. Concentrated along rivers, especially the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers, some may have been painted 9,000 years ago. Many are at least 5,000 years old, ranging from tiny five-inch animal figures to stunning eight-foot-tall human shapes with no arms or legs and alien-like bug eyes.

To find these remote panels, often at the intersections of 700- to 800-foot canyon walls, I have driven off-road and then hiked to remote locations to photograph the spectacular ochre-red paintings. The images of eerie, elongated figures with shortened arms and legs are hard to decipher. Of the anthropomorphs, or human figures, only 20 to 25 percent have eyes. Most have no ears or noses and no way to distinguish gender. Snakes writhe in their hands or above their heads. Yet circling these fierce, faceless creatures are delicate menageries of exquisitely painted birds, ducks, geese, deer, and, occasionally, free-floating eyeballs with wings.

The artwork is compelling. The brush strokes and vibrant paint pigments make the images seem fresh and newly painted, yet one carbon dating of an embedded hair from a paint brush dates from 6750 BCE. The paintings are usually a dark blood-red color, probably made by mixing blood and clay, and possibly using urine as a binder. The locations are often miles from the nearest paved road, in the remote recesses of Canyonlands National Park and on Bureau of Land Management lands across Utah, Colorado, northern Arizona, eastern Nevada, and parts of Wyoming. The most famous panels are the Great Gallery, Buckhorn Wash, the Holy Ghost Group, and the Harvest Panel.

Visual artist David Sucec, director of the Barrier Canyon Style Project, and photographer Craig Law teamed up more than 25 years ago to inventory this rare Archaic rock art style. Sucec received a Utah Humanities research fellowship to initiate the project. At the time, Sucec and Law thought there were about 160 Barrier Canyon art sites. Now they have found close to 450 outdoor paintings.

An exhibit of 24 of these photographs, with captions and wall text, is traveling for several years to local venues across Utah, with support from Utah Humanities in partnership with the Utah Division of Arts & Museums, allowing folks who may never venture deep into Colorado Plateau canyons to see these remarkable images.

The Barrier Canyon people did not farm. They created no distinctive architecture, but the art produced by these hunter-gatherers stuns observers who come around a corner in a deep canyon and see these enormous panels for the first time. The “billboard-sized” Great Gallery is 300 feet wide, with more than 80 figures, many near life-size.

“Utah’s first expressionist painters,” Sucec calls them. He adds, “Barrier Canyon style has emerged to be one of the two major Archaic Period painted-rock art styles in the United States and possibly in the entire New World.” Sucec says this is “a style that lasted, if the dates are correct, an amazing seven thousand years.”

He describes “virtuoso image-making techniques” and “life-size to heroic-scale anthropomorphic figures such as the Holy Ghost.” There are no violent depictions. No images of human conflict. Instead, there are “friendly associations of animal, bird, snake, and plant images with anthropomorphic spirit figures.”

The age and size of the images challenge our perspectives on American art and history. These are not human shapes as we would recognize them. Rather, they are human-like figures with elongated forms and interior spaces filled in with paint or cross-hatching, wavy lines, dots, zigzags, and snakes.

Unlike Europe’s ancient cave galleries of painted animals, Barrier Canyon images are composed of what Sucec has categorized as spirit figures, citizen figures, and composite figures. The spirit figures are obvious and look otherworldly. The citizen images are smaller helper-type figures that seem to hover around the spirits. Composite figures are just that—a combination of both. No leaping lions or thundering aurochs; instead, these are life forms with antennae and horns. Almost 90 percent of the images “are of the spirit-figure type.” Composite figures feature “combinations of body parts from dissimilar species.” Indian rice grass grows out of one figure’s fingertips, while rabbits gambol on its arm.

The traveling exhibit comes with handouts on “Why Teach Art?” and “The Language of Art.” For art detectives from the lower grades, questions are posed, such as “Why was it important for the photographer, Craig Law, to take all these pictures?”

“Walking in these canyons today,” Sucec explains, “it is not difficult to imagine the significance these ancient rock art galleries would have held for the hundreds of generations of a dynamic people who lived on the Colorado Plateau for a span, perhaps, of more than seven thousand years.”

Several years ago, I set out with a small group of friends to find a few remote Barrier Canyon sites. In side canyons and short slot canyons, we found them.

I can’t forget a blustery spring day with a storm front moving across Utah. Seven of us hiked all morning to finally find a few red symbols high on a cliff face shaded by a small alcove. We scrambled up. There in the silence of the San Rafael Swell, the few symbols seen below blossomed into small panels of intricate images expertly drawn.

Standing just a few feet from the panels, we could study the masterful brush strokes, the lyrical animal-like creatures, and the red paint’s perfect preservation. The artist had added a few white dots and faint white streaks. Seated on a sandstone ledge, looking south across a vast canyon landscape, rare pictographs just behind my shoulder, the twenty-first century melted away. Time ceased. I thought if we waited, with luck, the artist might return. Instead, there was only wind.