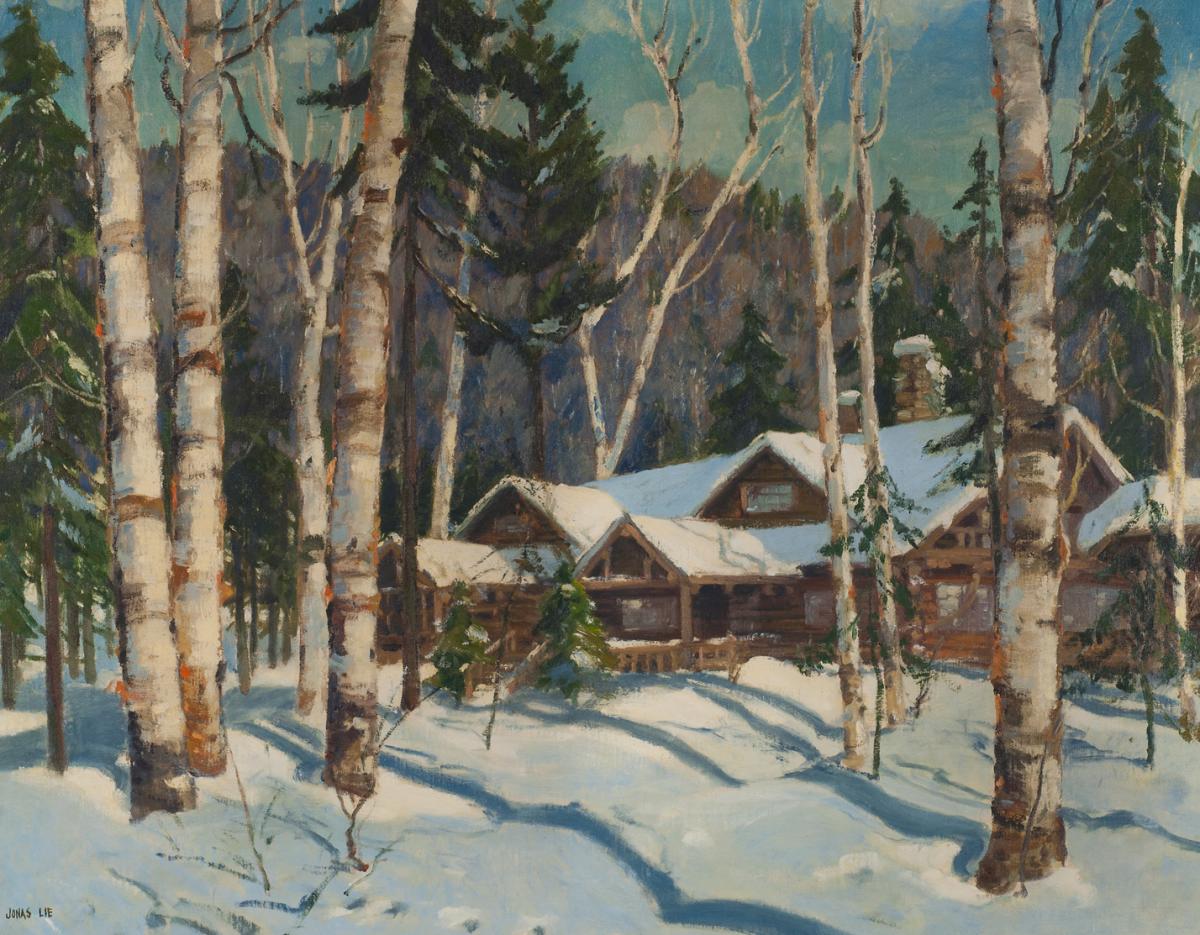

The Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York have been the subject of countless landscapes on canvas, paper, and film. What makes the region such a draw to creative spirits and tourists alike—what makes any special place special—is both a simple question and a challenging one. Fortunately, some very good answers may be found in the “Artists & Inspiration in the Wild” exhibition at the Adirondack Experience, The Museum on Blue Mountain Lake.

The new exhibition shows how four natural features of the region—light, forests, water, and mountains—have inspired a large and diverse group of artisans. More than 250 works reflecting this rich artistic heritage are on display in four themed galleries, with many of the pieces being viewed by the public for the first time this summer.

“From the first people to inhabit the region through today’s digital creators, artists have been deeply inspired by the beauty of this vast landscape. Their resulting works have shaped how we, in turn, think of and feel about the Adirondacks,” a gallery introduction reads.

A large variety of artwork is on display, including paintings, sculptures, carvings, ceramics, and textiles. “We took a broad view of what would fit in each gallery,” chief curator Laura Rice says. “Our goal was to connect people’s own experiences with the artists’ experiences.”

“Artists & Inspiration in the Wild” is the most comprehensive showing of the museum’s art and design collections since it opened more than 60 years ago. It’s a permanent exhibition, but not a static one, and the museum may bring in other historical and cultural acquisitions in the future, says Rice. “It’s the first time we’ve been able to put this much of the collection out on display,” she says. “We never had a place to do this artwork justice.”

The exhibition includes works by renowned artists such as Asher B. Durand, Thomas Cole, Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait, Seneca Ray Stoddard, and Rockwell Kent. Groundbreaking works of Edna West Teall, Dorothy Dehner, Margaret Bourke-White, Takeyce Walter, Niio Perkins, and Natasha Smoke Santiago, are also part of this inclusive and far-reaching interpretation of Adirondack art.

The state of New York created the six-million-acre Adirondack Park in 1892, making it roughly the size of neighboring Vermont, according to the private nonprofit Adirondack Council.

The region is best known for its expansive and pristine forests, mountains, lakes, and rivers, which support recreation in all four seasons. What makes the Adirondack Park unique is that it contains both public lands protected by the state and private lands filled with rural communities and year-round residents.

The Adirondack Park is home to 130,000 permanent and 200,000 seasonal residents, with more than 12 million visitors to the region each year, according to the Adirondack Council.

To appeal to a diverse population of residents and visitors, the Adirondack Experience designed its newest exhibition to “bridge the divide between art lovers and the rest of the public,” says executive director David Kahn. “We wanted to make the Adirondack art accessible for a family audience, because we believe art is for children as well.”

The impressive trove of materials on display spent years hidden from public view, packed in cardboard boxes and other storage containers in the basement of an older building. When construction of the 6,000-square-foot building started in the late 1950s, “it was being built under different standards of that time,” Kahn says.

“It was not built with a vapor barrier or enough insulation, and there was no indoor humidity control,” he adds. “We used to get ice buildup in corners, and as a result, we had indoor leaks on a regular basis.” The leaks in the ceiling and walls created a potential risk of damage to any artwork on display, including paintings hung on the walls.

Throughout the years, art would be periodically taken out of storage and temporarily put on display in one of the museum’s other buildings. The Adirondack Experience has a vast collection of historic and cultural items in more than 20 buildings that sit on 120 acres overlooking Blue Mountain Lake.

But this summer, for the first time, the majority of artwork by the artists came out of the basement and found a permanent home in one of the four galleries of the newly renovated structure. “This is the first time we’ve had an area specifically earmarked for the display of art,” says Kahn.

The $5.5 million project to create a permanent home for the Adirondack art was made possible with public and private support, along with several grants, including a $500,000 matching one from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The NEH grant was vital for the capital project, Kahn says.

“We needed to do a gut rehabilitation so only the outer walls and rafters were left,” he says. “Then we rearranged the walls to create the different galleries.” A new HVAC climate-controlled system was also installed to keep the temperature in a range that would protect the artwork.

“There are many hands-on interactive things here to make both children and adults happy,” Rice says. “It’s not a traditional art exhibit.” The new exhibition is truly a sensory one and offers a total of 18 different interactive elements spread throughout the four galleries.

It aligns with the museum’s objective of offering “experiences” to help people better understand the deep history and culture of the Adirondack region. Along the grounds, there are numerous family-oriented activities: Visitors can climb a classic Adirondack fire tower, row an authentic guideboat, and hike around scenic Minnow Pond. Classic Adirondack chairs are scattered throughout the grounds.

“Artists & Inspiration in the Wild” features a corner display of paintings by the late artist Edna West Teall (1881–1968), who grew up on an Adirondack farm. Self-taught, she started painting only after she had retired. Teall recreated scenes from her childhood, depicting her family making maple syrup, feeding chickens, and attending a church social.

Her works from the 1950s and ’60s are accompanied by an interactive touch screen that brings to life her paintings and her children’s book, Adirondack Tales: A Girl Grows Up in the Adirondacks in the 1880s. As each screen is touched, a painting appears, and the figures move on screen while a passage from her book is narrated.

“Pack Your Pack Basket” encourages visitors to imagine what an artist climbing an Adirondack mountain more than 100 years ago might need for the journey to catch the panoramic views on canvas—such as artist tools, a wool jacket, and extra socks.

“These artists spent hours on top of these mountains, [which] were such an inspiration to them,” Rice says. “But there is another angle of what it took for them to get to the top. They had to travel here by steamboat, train, and stagecoach. And they had to be self-sufficient, able to prepare a fire and cook deer and fish.”

“Touch This” encourages visitors to examine the furniture, photographs, baskets, carved fungus, watercolors, and oils of Adirondack artists. A table filled with various materials allows visitors to feel different textures that appear in work throughout the exhibition.

Next to some of the artwork are personal reflections from those living in Adirondack communities. Several were asked to provide their insights into works done by artists who have since passed away.

Samantha LaFond, a local taxidermist, provides her interpretation of Going Out: Deer Hunting in the Adirondacks, 1862, by well-known painter Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819–1905). A British American artist known for his wildlife paintings, Tait emigrated to the United States in 1850 and settled in New York City but established a painting camp in the Adirondacks to explore and capture the enchanting wilderness on his canvas.

About his 1862 painting, LaFond wrote, “After a successful day’s hunt, good company and a night’s rest, A. F. Tait shouts ‘see you down the line’ to his good friend while his Adirondack guide, ‘Captain’ Calvin Parker, prepares the boat for another great day in the wilderness.”

The new exhibition highlights several of Tait’s Adirondack paintings, including Autumn Morning, Racquette (sic) Lake, 1872; Still Hunting on the First Snow: A Second Shot, 1855; and Fishing Through the Ice, 1854.

Several living artists provide comments for their own works. For the modern-day painting, Dock, 2017, artist Joe Remillard, (b. 1956), wrote, “The never-changing beauty of this place makes it sacred and reassuring. I paint the people and places in my life that I love. Silver Lake and this dock are one of those places.”

The designation of the four different natural elements helps distinguish the particular focus of each artist. Two paintings from the Civil War period are displayed side-by-side in the light gallery, and the contrast of the work done by two painters—one at the beginning and one at the end of the war, “make for an insightful commentary on the war and how people were feeling at the time,” Rice notes.

The painting A Twilight in the Adirondacks, 1864, by Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–1880) was painted by the artist shortly after the loss of his brother. “Gifford bathed this landscape in brilliant yellow, orange, and red light. Painted at the peak of the Civil War, the work depicts the drama of a true sunset while reflecting sorrow and anger at the human and spiritual costs of the ongoing conflict. Grief at losing his younger brother, Edward, this same year added to the depth of feeling Gifford conveyed in this view,” reads the description.

In a painting done a few years later, the light reflects a more hopeful nation. Mountain View on the Saranac, 1868, by Homer Dodge Martin (1836–1897) “shows the Saranac Lakes from Ampersand Mountain. Martin created a soft, hovering light to depict the Adirondacks as a source of peace, spirituality, and healing. Painting shortly after the Civil War, he chose not to make an exact rendering of a view, but rather an imagined Adirondacks expressive of the collective relief that the conflict was over.”

The collection also explores art by Native Americans. “Many Indigenous people lived in these parts, and it’s still their home. We wanted to recognize them as part of the artist community,” Rice says.

Stolen/Broken Connections, 2021, by Natasha Smoke Santiago, Akwesasne Mohawk, (b. 1983), is a fire-smoked ceramic bowl that addresses an important part of the Native experience, one that is receiving more attention these days. “This work is about the residential schools. There have been many Native people affected by the residential schools across the U.S. and Canada.” Noting how her grandparents had been forced to attend these schools, she wrote, “I wanted to shine a light on the story of residential schools and the children who were affected. Their language was taken. Essentially their lives were taken.”

A delicate velvet collar by Wilma Cook Zumpano, who is also Akwesasne Mohawk, carries a heartfelt tribute. Crown and Collar, 2016, was created by the artist for her daughter’s college graduation ceremony. “I knew I had to make her something special since she was the first graduate from our family to finish a four-year degree. She loves butterflies, so I beaded one at the center of the collar, right close to her heart. It stands for her to soar to her heart’s content, that the world is ready for her,” the artist wrote.

The newly renovated building includes an art lab or “maker space” that allows adults and children to create their own Adirondack art. The space was created in collaboration with Adirondack artist Barney Bellinger, who brought in tools and materials from his own studio.

Bellinger is a painter, sculptor, photographer, and furniture maker. A native of Johnstown, he is a self-taught artist who immersed himself in the beauty of the Adirondacks to create his works, which have been displayed at the Adirondack Experience, the National Museum of Wildlife Art, the Orvis Company, and the Smithsonian Institution.

The materials and projects in the art lab are inspired by the works of many different Adirondack artisans, some of whom offer workshops throughout the season and participate in the museum’s summer artist-in-residence program.