“My favorite season is in midsummer,” wrote William Henry Harrison Murray in his guide to the Adirondacks, where he had camped for months at a time, and fished, hiked, and climbed the region’s peaks to witness the “lily and marsh flowers in bloom.”

The Adirondacks, a mountain range in northeastern New York State, offered a “sublime sight,” in Murray’s account, including that of a summer storm coming majestically over Blue Mountain. “The preacher sees God in the original there,” Murray wrote.

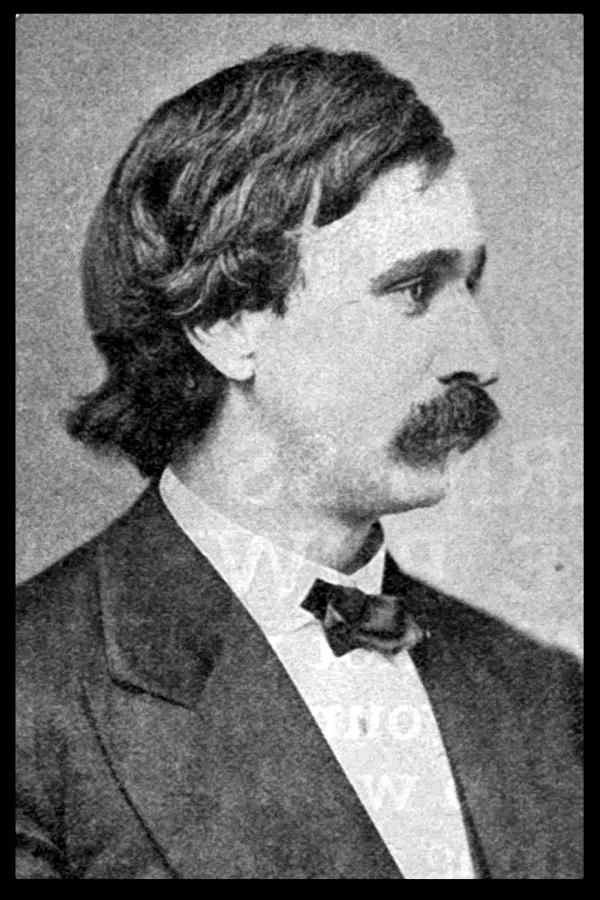

He would know. Murray was pastor at Boston’s Park Street Church, from which he hobnobbed with the city’s elite and gained a national reputation as a speaker and an author. In 1840, the year William Henry Harrison was elected to the White House, Murray was born into an impoverished farm family in Guilford, Connecticut. He attended school and discovered a talent for oratory that led him to captain the debate team. He organized Guilford’s Clionian Society, one of the era’s many literary clubs for young men. At Yale, Murray felt called to the ministry. Following studies at the East Windsor Theological Seminary, he pastored churches in New York, Connecticut, and Washington before shepherding the Park Street Church from 1868 to 1874.

Murray’s first trip to the Adirondacks was in 1864, when most of the nation knew nothing about New York’s north country wilderness. He began writing articles describing his Adirondack trips, and, in 1869, he published Adventures in the Wilderness; or, Camp-Life in the Adirondacks. It became an instant hit. Murray’s guidebook beguiled world-weary souls from the era’s professional classes who felt beaten down by the crush of city life. Rapt, they came. “Murray’s Fools,” as they were called, rushed to the Adirondacks, mostly unprepared for their adventure in the wilderness but eager to experience the bodily and psychic restoration Murray said the woods and mountain air provided.

Murray popularized an idea of wilderness that was rather new. At the time, wilderness was still forbidding, a place of evil or at least of obstacles to be overcome. But the Romantics, including Transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson, who feted Murray during his years in Boston, saw nature as beautiful and sublime. Emerson’s essay “Nature” preached communion with God among the trees, pure divinity amidst unspoiled land. Murray’s Fools followed in their footsteps, seeing in nature a resource worth tapping for spiritual and psychic benefit.

Murray’s book included information to help visitors navigate the considerable transportation obstacles involved in traveling from New York City or Boston to the Adirondacks. He gave readers an itinerary that had them leaving Boston on Monday morning aboard the Boston and Albany Railroad and arriving at Lower Saranac Lake by dinnertime on Tuesday. The long trip included an overnight steamboat journey on Lake Champlain and two stagecoach rides over plank roads for the remaining 62 miles.

Murray profiled hotels and inns that sprang up to accommodate tourists. He offered advice on hiring guides. “A good guide, like a good wife,” he noted, “is indispensable to one’s success, pleasure, and peace.” Avoid the “hotel guide,” he urged, as those are hired by hotel-keepers for the season and were generally “inferior in character, skill, and habits to the others.” Murray preferred the independent guides, a “capable and noble class of men” whose success depended on endorsements from happy customers.

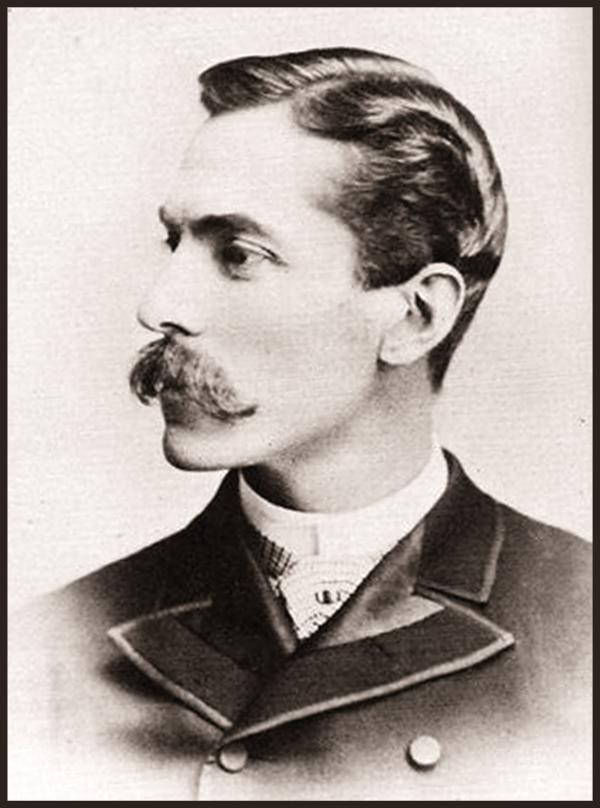

Adventures in the Wilderness appealed to an audience of middle class vacationers, but other entrepreneurs imagined other visitors. Thomas “Doc” Durant, the railroad baron, looked to capitalize on the growing enthusiasm for wilderness vacations by developing the region as a playground for the nation’s elite families. He and his son, William, invented the Great Camp, a rustic precursor to the seaside “cottages” crowding places like Newport, Rhode Island, later in the century. While some may have seen nature as a great leveler, the Adirondacks merely replicated the social divisions characterizing the Gilded Age.

Born in 1820, Durant trained as a doctor, but he eventually traded the surgeon’s scalpel for the financier’s stock offering. By the 1850s he had become involved in railroads. He founded the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad and used it to position himself to take advantage of the nation’s transcontinental desires. His drive was captured by an 1867 phrenological assessment, which described him as a “highly-bred race-horse . . . active, wide-awake, restless, impatient, nervous, intense.” His “mile-a-minute” disposition may have led to cutting corners and placing profit before probity. He bankrolled his takeover of the Union Pacific Railroad, for example, with money he made by smuggling Confederate cotton during the Civil War.

With some of his plunder, he started buying up vast tracts of the Adirondack forest. Other parcels he secured from New York State, which gave his Adirondack Railway Company land in exchange for building lines connecting Saratoga Springs to North Creek. Durant became one of the largest landowners in New York’s North Country. These Adirondack assets were all he had left to launch his comeback following his precipitous fall from grace.

The 1873 financial panic wiped out most of his Union Pacific Railroad profits. He was also implicated in the Crédit Mobilier scandal. Durant had created this sham company to funnel proceeds from railroad construction contracts to him and his associates, including members of Congress, who accepted bribes in the form of Crédit Mobilier stock. When the scandal broke, it snagged nearly 30 congressmen, including James Garfield, who was nevertheless elected president eight years later.

Disgraced and insolvent, Durant retreated to the Adirondacks to orchestrate his revival. His comeback focused on developing his landholdings. He tasked his son, William, whom he brought home from his world travels, with developing exclusive living and recreational spaces that would become known as the Great Camps. Over time the Great Camps developed their defining features: a lake-front, self-sustaining compound with specialized buildings for sleeping, dining, and entertainment, in addition to work buildings, including boathouses, blacksmith shops, carpentry sheds, laundries, kitchens, and barns. The Great Camps employed skilled craftsmen and laborers, including staff, to attend to the needs of family and guests. A final defining feature was the creative use of locally sourced building materials. For Durant’s camps, this meant quarrying local granite for fireplaces and girdling birch trees to use for siding.

Durant died in 1885, but William carried on the work of building Great Camps. He started with Camp Pine Knot, which he built on Long Point, a thumb-shaped peninsula jutting into Raquette Lake’s South Bay. He sold Pine Knot to Collis P. Huntington in 1895. Huntington died there five years later, and the Huntington family never returned. (Since the 1940s, when the State University of New York at Cortland assumed ownership from Huntington’s son Archer, it has been known as Camp Huntington.)

After Pine Knot, William built Camp Uncas on Lake Mohegan and then Camp Sagamore on Shedd Lake. In these camps, Durant refined his vision of Great Camp architecture. At Pine Knot, guests slept and played within earshot of working craftsmen and waiting servants. At Camps Uncas and Sagamore, however, Durant moved those who worked and served away from those who came to play. At Sagamore, an upper complex for workers was a good hike away from the lakeside camp. Uncas was developed on a grander scale than Pine Knot. It featured larger fieldstone fireplaces and elaborate structures for housing and entertaining guests and for boating and for storing chopped wood. Built on a strategic outcropping on Lake Mohegan, Camp Uncas had two distinct views of the water and the surrounding forest and hills. Whereas visitors to Camp Pine Knot looked across the lake and could see signs of other people, guests at Uncas and Sagamore hiked, swam, and fished in blissful solitude.

William Durant was a visionary architect but a poor businessman. Facing a $20 million judgment against his father’s estate from the Crédit Mobilier swindle and protestation from his sister regarding her share of the family inheritance, Durant inexplicably commissioned the construction of a $200,000 yacht. Soon thereafter, he was elected a member of the New York Yacht Club but was unable to pay his bills. Turning to his father’s business associates, Durant found J. P. Morgan a willing creditor. In 1896, one year after Camp Uncas was complete, Durant sold the property to Morgan under financial duress.

Durant’s Great Camps are architectural marvels, but they are also Gilded Age curiosities. They embody the era’s excesses and contradictions. Just as in the novel Mark Twain coauthored with Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age, which gave the period its name, the Great Camps presented facades, surfaces, and veneers. Built for a class with power and influence, Great Camp owners had the resources to stage experiences and sleights of hand. In the process, they destabilized conventions and reaffirmed them at the same time.

Durant’s camps extolled the Romantic view of nature John Muir popularized. “Come to the woods,” Muir urged his readers, “for here is rest.” Durant hoped to envelop the camps and their visitors into the surrounding nature through artful construction: sheathing the buildings in birch bark, ornamenting porches with scavenged branches and twigs, and crafting fireplaces of native stone in which the chisel marks were carefully hidden from view. At Sagamore, servants wet the fireplaces to encourage the growth of moss, maintaining the illusion of the natural world even indoors. Durant sited buildings so they seemed to be part of the surrounding wilderness, not an intrusion upon the land. Camp aesthetics attempted to erase boundaries separating people from nature.

The wilderness as Durant’s clients experienced it was made to seem simple and natural, but it was full of modern convenience. Guests washed in porcelain sink basins and soaking tubs. At Camp Sagamore, buried lines transmitted power from a hydroelectric generator hidden in the forest. Sagamore’s layout, with an upper camp for the workers and a lakeside camp for guests, screened one from the other. Alfred Vanderbilt, the billionaire son who purchased Sagamore from Durant in 1901, built a guesthouse called Wigwam to entertain his male friends. It sported a permanent lean-to with a massive stone firepit and call box to summon the butler when the champagne ran low.

These camps were also spaces where the period’s gender ideals were displayed and sometimes challenged. For the “over civilized” man of the nineteenth century, the Adirondacks offered a wilderness experience to test his mettle. Hunting, fishing, and hiking reconnected him to nature, but artifice was the true name of the game. Local guides paddled visiting “sports” to stocked lakes, and they flushed deer to ensure successful hunts. A Sagamore guide once revealed that he had held a deer by its tail to give a visiting sport a shot at claiming the prized antlers, destined for display in his Manhattan study, a trophy commemorating his triumph over nature.

For women, these Adirondack camps both disturbed gendered expectations and reaffirmed them at the same time. Female guests swam in the cool lakes, fished in the rivers, and even hunted. They hiked dense forests and climbed mountain peaks. Afterward, servants helped these women into their corsets and hoop skirts for the formal dinners that ended each day’s adventure. The wilderness stretched, but did not snap, dominant ideals of womanhood.

It also did not purify the machinations and George Plunkittesque graft that defined Gilded Age politics. As the Adirondacks became more popular, both among vacationers and entrepreneurs, a conservation and preservation ethic coalesced around efforts to protect the wilderness. Much of the impetus came from downstate. Members of the New York Board of Trade and Transportation, for example, were convinced by George Perkins Marsh’s argument in Man and Nature that deforestation negatively impacts watershed. Verplanck Colvin, the superintendent of the Adirondack Survey, argued in 1873 that clear-cutting in the Adirondacks would reduce water flow to the Erie Canal and the Hudson River.

Members of the Board and Trade and Transportation, eager to protect New York’s commercial waterways, pushed reforms that ultimately led to the ratification of the 1894 state constitution, which included protections for the state’s “wild forest lands.” Article 7 stipulated that “lands of the State, now owned or hereafter acquired, constituting the Forest Preserve as now fixed by law, shall be forever kept as wild forest lands. They shall not be leased, sold, or exchanged, or be taken by any corporation, public, or private, nor should the timber thereon be sold, removed, or destroyed.” Lumber barons were, not surprisingly, outraged by the vote but so too were many conservationists, like Gifford Pinchot, who believed scientific forestry could manage the state’s timber resources. But New Yorkers rejected both the ax and the expert.

Great Camp owners benefitted enormously, however, from this legislation, an unintended consequence that bent a public good into a private gain. Owners could surround their private camps with protected state land, insulating their retreats from future development. Some even deeded portions of their landholding to the state, thus escaping property taxes while benefitting from the Forever Wild protection that preserved their pristine and unspoiled views. Like the period’s industrialists who co-opted commissions established to regulate them, proprietors of the Great Camps took advantage of the protections afforded by the 1894 constitutional provision to benefit themselves.

The history of the Great Camps, full of paradox and contradiction, is ultimately a story of competing visions. William Murray’s Adventures in the Wilderness democratized the Adirondacks, opening the region to a growing middle class seeking relief from urban life. The Durants participated in this democratization by building rails and stagecoach lines to accommodate travelers, but the Great Camps were rustic extravagances built to satisfy the wilderness fantasies of the nation’s elite families. The first Gilded Age, like our second one, was about money and power. Access to the wilderness, and the ability to determine who gets to use that land, defined North Country politics of the latter nineteenth century. It continues to do so today. Where is the compromise that preserves the wilderness landscape yet opens it to tourism and development? In the vast Adirondack landscape, we are still searching for common ground.