The Letters of Ernest Hemingway

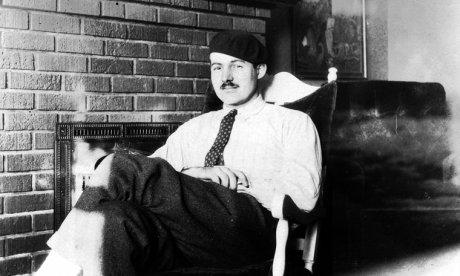

Ernest Hemingway, Paris, circa 1924

Wikimedia

Ernest Hemingway, Paris, circa 1924

Wikimedia

Late last year, the Hemingway Letters Project and Cambridge University Press brought out the second of a projected seventeen volumes of The Letters of Ernest Hemingway. Its 242 missives, telegrams, and book inscriptions (all with detailed annotations) cover the period from 1923 to 1925, when Hem was living the expat-artist’s dream: base of operations on the Left Bank; excursions to Rapallo, Pamplona, Schruns, and Provence; writing, drinking, skiing, fishing, and more drinking among the foremost of the Lost Generation. Taken together, the letters present a rich and, until now, unseen self-portrait of the not-yet famous Hemingway, a young man honing his craft with the help of Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein and gathering material for his groundbreaking short story collection, In Our Time, and the novel that made his career, The Sun Also Rises.

The Letters Project volumes are a scholarly endeavor, to be sure; but Hem himself, even half a century after his suicide, is too big for the ivory towers alone. Outlets from the New York Times to the Australian have weighed in, calling Volume 2 “an exceptional collection, magnificently collated,” and its editors, who expect to spend 20 years completing the set, “tireless.” The Spectator asked, “Does the world need 17 volumes of Hemingway’s letters?” and, after working through the latest, found that “there is no denying that the letters are of interest, although the interest is necessarily patchy, given the inclusion of everything from financial instructions to stockbrokers to artistic advice to F. Scott Fitzgerald.”

But, of course, as the Telegraph, Star Tribune, and Independent point out, it’s precisely the thoroughness of the collection, the light that it sheds on so many different facets of the author’s life, that makes it such a valuable resource for scholars and such a pleasure for “the serious Hemingway fan.” The letters suggest, for instance, how much (or, rather, how little) Hemingway made from his writing during those early years, what books he read and how he reacted to them, that he was capable of expressing insecurity, and (this is the real surprise) that he could be genuinely funny. The Independent cites Hem’s takedown of Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End as proof of the last: “Ford is onthe [sic] third vol of his collossal [sic] trilogy of The Soldier (British) as represented by the Master himself. This refers to Ford not to Christ. Readers confidently expect that in this last Vol The Soldier will actually reach the FRONT. Personally I don’t think the Master will dare risk it. Christ what an orgy of stylistic faking it will be if he does.”

Although it’s easy to read right past all but the big names among Hemingway’s correspondents—Fitzgerald, Pound, and Stein—reviewers haven’t overlooked the sometimes much more interesting letters to his buddies back home, Bill Smith and Gregory Clark, on bullfighting and “the question of brutalidad.” To Clark, Hemingway wrote enthusiastically about the “tragedy” (in the theatrical sense) of the bull’s death (“God how it’s played!”). To Smith, he sent an unpublished short story on the subject and truly rough first drafts of several passages that, extensively reworked, ended up at the heart of The Sun Also Rises. Here’s one: “You know the picadors are never in longer than 10 minutes with each bull—usually less— When anything bad happened I told her”—Hadley, Hem’s wife at the time—“to look away. She done so. Finally she looked all the time. Just found it didnt [sic] buck her.” And here’s another, its cadence approaching the familiar rhythms of Hemingway’s more polished prose: “Now a horse with his tripe hanging out isnt [sic] pitiful. It’s funny. But he isn’t. He’s grotesque. There isn’t anything that isn’t grotesque about a dead horse.”

In their own fast-paced way, Web-only publications are plugging the letters as well. The Daily Beast reprinted, without comment, what it described as a “Macho Letter” from Hemingway to Fitzgerald that reads, in part: “To me heaven would be a big bull ring with me holding two barrera seats”—first row—“and a trout stream that no one else was allowed to fish in and two lovely houses in the town; one where I would have my wife and children . . . and the other where I would have my nine beautiful mistresses.” Jezebel responded promptly with a short piece titled “That Time Ernest Hemingway Described His Ideal Bro Paradise,” elaborating Hem’s vision with a few sarcastic details: “There’ll be an old bank of novelty pinball machines, an air hockey table, a dart board, and THREE pool tables. NO CHICKS,” etc. Not the most informed exchange on the author’s life and work, but it shows at least that Papa Hemingway, who redefined American literature so many years ago, can still rile a few readers.