NEH Supports Strategic Collaborations in Native American History, Languages, and Cultural Revitalization

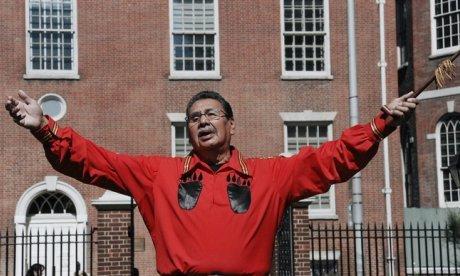

Larry Aitken performs a pipe ceremony in Philadelphia, May 2010

Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society

Larry Aitken performs a pipe ceremony in Philadelphia, May 2010

Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society

This feature initiates a new series of articles that explore the results of NEH grants across the agency’s divisions and offices. The series will provide an in-depth look at NEH projects that cover a particular discipline, culture, or historical period, or that involve new technologies or methods that advance education, research, and public programming in the humanities.

For this inaugural article, we explore the role that NEH plays in supporting documentation and teaching of Native American languages, history, and culture. First, we feature a project from the Division of Education, a collaborative effort undertaken by the Leech Lake Tribal College in Cass Lake, Minnesota, to make Ojibwe cultural history accessible online to tribal members, teachers, and the public. Next, we highlight a project in the Division of Preservation and Access that will bring to light an 18th-century Jesuit manuscript that can increase our understanding of the Miami-Illinois language. The language, once spoken in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, is presently undergoing a rebirth through the efforts of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. And finally, we explore a project funded through NEH’s Office of Challenge Grants to the Northwest Indian College, located in Bellingham, Washington, which is developing programs to preserve the culture and revitalize the language of the Salish people.

Digital Repatriation, Cultural Revitalization, and Traditional Values: Leech Lake College and the Ojibwe

American cultural institutions hold vast amounts of material–documents, artifacts, and audio and video recordings–gathered from Indian tribes. Tribal communities in Minnesota have been working with the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the American Philosophical Society, and the Minnesota Historical Society to develop a digital archive of Ojibwe cultural heritage that allows these communities to tell their history on their own terms. Through a series of NEH awards, including the most recent 2011 Humanities Initiatives at Tribal Colleges grant, to Leech Lake Tribal College, the tribes are using “digital repatriation” to bring home in digital form the beaded bags of their ancestors, recorded songs, historical photographs, census rolls, maps that document their homelands, and other materials that originated from their communities (see Photo Gallery). This unique partnership between the Ojibwe tribal colleges–Leech Lake Tribal College, White Earth Tribal and Community College, Itasca Community College, and Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College–and the institutions that house their cultural heritage is exploring how digital technology can resolve problems of access and sustainability, while enhancing cultural diversity in the digital humanities. It is also serving as a model for how collaborations across different cultural communities can lead to mutually beneficial relationships.

The partnership had its ceremonial beginnings at a meeting held at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, where tribal historian Larry Aitken performed a Sacred Pipe Ceremony and offered prayers to “awaken” the cultural objects so they can be digitized and returned to the Ojibwe people for language documentation and cultural revitalization (see Photo Gallery). The process has brought together educators, scholars, archivists, and media specialists to discuss how state-of-the-art digital technology can be best employed to present ancient traditional Ojibwe knowledge while honoring and respecting cultural integrity.

Over the course of the grant period, Ojibwe knowledge keepers, including tribal historian Larry Aitken, worked with humanities faculty at Leech Lake Tribal College to create videos explaining important aspects of Ojibwe language, history, and culture. These videos can be incorporated into the curriculum at partner institutions and are used in the Ojibwe Quiz Bowl, a competition that focuses on Native American cultural knowledge for high school students across Minnesota. The videos are housed on the Gi bagadin-a-maa goom digital archive, hosted by the University of Pennsylvania. Gi bagadin-a-maa goom is an Ojibwe word that means “to bring to life, to sanction, to give permission.” While not an easy name to Google, as the directors point out, the name of the Web site alerts viewers that they are entering into a world of traditional Ojibwe culture where navigation through the site follows the seven sacred directions of Ojibwe cosmology. As the project advances, it will include documentary materials and cultural objects housed at the partner institutions. Images of some of these have already been digitally repatriated to the college libraries where they are accessible to students and tribal members.

Timothy Powell, one of the project coordinators, has been active in sharing the results of this project with historians, anthropologists, and scholars of Native American studies to show how the digital humanities can help Indian communities tell their own stories. It is the goal of the Gi bagadin-a-maa goom archive to show that it is possible to expand what Powell calls “the digital imaginary” to include audio, video, and material culture viewed from the perspective of Ojibwe wisdom-carriers. The partners have engaged in an extensive planning process, parts of which are documented in the 2010 meeting placed on YouTube.

Using Old Records to Educate a New Generation: the Miami-Illinois Dictionary Project

There are today between 150 and 175 Native American languages spoken in the United States, though the number was once in the thousands. Hundreds of languages have been lost while others are endangered and likely to disappear in the next few decades. Tribal efforts to teach new generations about their heritage language depend on the existence of linguistic materials that can be used in workshops and training programs. These include documentation, such as recording native speakers, eliciting phrases and vocabulary, compiling grammars and word lists, as well as producing dictionaries and other related linguistic resources. The Miami University in Ohio, funded last year through NEH’s Division of Preservation and Access, is preparing an annotated digital edition and translation into English of an 18th-century Miami-Illinois dictionary. The dictionary (see Photo Gallery) was compiled by a Jesuit priest, Jacques Le Boullenger, who lived and worked among the Illinois natives from about 1720 to 1740. Written in both French and Miami-Illinois, the dictionary contains critical language and ethnographic detail about Miami-Illinois culture and the physical environment in the Great Lakes area in the early colonial period, including uses of plants, diet, and the climate. It consists of 185 pages with 3,000 word entries and concludes with devotional texts.

The last speaker of the language died in the early 1960s. Early attempts in the 1990s to revitalize the dormant Miami-Illinois language made it clear that the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma needed a more extensive infrastructure to develop essential language teaching materials. The Myaamia Center, based at the Miami University of Ohio, emerged as a unique collaboration of tribally-directed research in a university setting.

The goal of the current project is to make the data contained within the dictionary available to students of the Miami-Illinois language, linguists, researchers, and the general public. The original document has been scanned by the John Carter Brown Library, where it is permanently housed. Digital files have been sent to the Myaamia Center, where researchers transcribe the original handwritten French and Miami-Illinois and organize it for translation into English. Once the transcription work is complete, Michael McCafferty at Indiana University in Bloomington, translates the French terms into English, and David Costa, a project co-director, in turn, translates the Miami-Illinois into English. As an independent consultant for the Myaamia Center, David Costa serves as the director of the Office of Language Research for the Myaamia Center. When completed, the online dictionary will offer digitized images of the original document and provide searchable text for the French, English, and Miami-Illinois terms. Project director, Daryl Baldwin, has been instrumental in developing language teaching materials and leading community efforts to revitalize this once-sleeping language (see Photo Gallery). The materials developed under this award will help him and others teach the language to current and future generations of the Miami tribal community.

Rebuilding the Salish Institute: Construction, Renovation, and Capacity-Building at Northwest Indian College

At the opposite corner of the country, NEH funding is making it possible for Northwest Indian College’sCoast Salish Institute (CSI), located in Bellingham, Washington, to escape the cramped confines of an old modular building, where inadequate space had effectively put the brakes on critical research and educational programming about North America’s Coast Salish people. Soon, thanks to an NEH Challenge Grant, the institute will be moving to a new 12,710 square-foot structure that includes culturally appropriate language labs, video production areas, distance-learning technology, and space for archives, classrooms, and large events (see Photo Gallery). Students and faculty at the college will have both the room and the resources to work on language preservation projects, promote Coast Salish cultural arts, and develop culturally relevant curricula. Tribal scholars will also have the opportunity to share their knowledge and to showcase their experiences at the Institute. According to Sharon Kinley, CSI’s director, these “scholars are community-based—often untrained in Western research and teaching methodologies and practices—but are individuals who carry out the most sacred work of preserving and revitalizing” Coast Salish cultural traditions.

The new facility will allow the Institute—which Northwest Indian College touts as the only entity in the world that exclusively focuses its scholarly efforts on a study of Coast Salish peoples—to serve as a repository of knowledge and culture for museums, civic organizations, institutes of higher education, scholars, and indigenous peoples the world over. The new building will be a place where people—Native and non-Native—can gather to engage in conversations about Coast Salish peoples and to learn about their histories, philosophies, legends, languages, cultures and more. Resources currently scattered across various locations will be more easily pooled, cataloged, and made available for use and study on a regular basis.

Selected Resources on Native American History, Languages, and Cultural Revitalization

Documenting Endangered Languages, a partnership of NEH and the National Science Foundation

http://www.nsf.gov/funding/pgm_summ.jsp?pims_id=12816

PBS series, We Shall Remain

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/weshallremain/native_now/language

EDSITEMENT lesson plan

http://edsitement.neh.gov/feature/celebrate-we-shall-remain-native-american-heritage-month

Newberry Library

http://publications.newberry.org/indiansofthemidwest/

Teaching indigenous languages

http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~jar/TIL.html

UCLA Teaching Materials for less commonly taught Languages

http://www.lmp.ucla.edu/Profile.aspx?menu=004&LangID=197

The American Indian Languages Development Institute

http://aildi.arizona.edu/

The Indigenous Language Institute

http://www.ilinative.org/

Breath of Life Workshops

http://nal.snomnh.ou.edu/okbol

http://www.endangeredlanguagefund.org/BOL.php

Timothy Powell, A Drum Speaks: A Partnership to Create a Digital Archive Based on Traditional Ojibwe Systems of Knowledge, September 21, 2007 RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage vol. 8 no. 2 167-180.

http://rbm.acrl.org/content/8/2/167.short