Mark Twain II

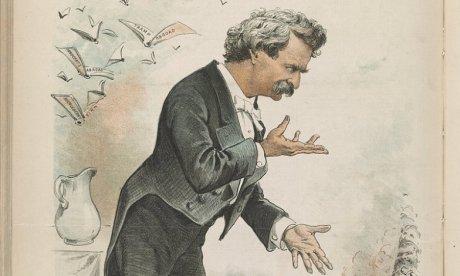

"Mark Twain, America's best humorist," lithograph, c 1885

Library of Congress

"Mark Twain, America's best humorist," lithograph, c 1885

Library of Congress

The second volume of Mark Twain's autobiography features nearly 700 pages of Twain's worldview. It's a blend of his trademark humor and dudgeon directed at the politicians and other luminaries of his day. Full of affection for the afflicted and scathing about those who afflict them, this new work, funded in part over half a century by the National Endowment for the Humanities, displays the unvarnished Twain.

Here's a taste of what he had to say:

On Theodore Roosevelt:

“I am not jesting, but am in deep earnest, when I give it as my opinion that our President is the representative American gentleman—of to-day. I think he is as distinctly and definitely the representative American gentleman of to-day as was Washington the representative American gentleman of his day. Roosevelt is the whole argument for and against, in his own person. He represents what the American gentleman ought not to be, and does it as clearly, intelligibly, and exhaustively as he represents what the American gentleman is. We are by long odds the most ill-mannered nation, civilized or savage, that exists on the planet to-day, and our President stands for us like a colossal monument visible from all the ends of the earth.”

On belief:

“There isn’t anything so grotesque or so incredible that the average human being can’t believe it.”

On a fondly remembered steamboat:

“When she was on a voyage there was nothing in her to suggest a steamboat. One didn’t seem to be on board a steamboat at all. He was floating around on a farm. Nothing in this world pleasanter than this can be imagined.”

On humor and preaching:

“Humor must not professedly teach, it must not professedly preach; but it must

do both if it would live forever. By forever, I mean thirty years. With all its preaching

it is not likely to outlive so long a term as that. The very things it preaches about, and

which are novelties when it preaches about them, can cease to be novelties and become

commonplaces in thirty years.”

What he sees when he closes his eyes:

“Although I can neither draw nor paint, my mind often draws and paints the most exquisite and the most faultless faces—faces of strangers always—when I am almost asleep but yet dimly conscious of my surroundings. These faces are very small. In size and quality they are like the old-fashioned ivory miniatures; like, but not just like, for they are much more dainty and charming and beautiful than any ivory miniatures that I have ever seen; by contrast with them the ivory miniature is coarse and unspiritual.”

On anti-Semitism:

“I have no prejudices against Jews. I have nothing that resembles a prejudice against Jews. To me, Jews are just merely human beings, and to my mind the difference between one human being and another is not a matter of the slightest consequence. As between a crocodile and an alligator there is no real choice, to my mind, therefore why should there be a choice between Jew and Christian—or between anybody and anybody else? To be a human being of any kind is a hard enough lot, and unpleasant and disreputable in the best of circumstances.”

On Bret Harte:

“He was a man without a country; no, not man—man is too strong a term: he was an invertebrate without a country. He hadn’t any more passion for his country than an oyster has for its bed; in fact not so much, and I apologize to the oyster.”

Why he presumes to speak so authoritatively:

“The last quarter of a century of my life has been pretty constantly and faithfully devoted to the study of the human race—that is to say, the study of myself, for, in my individual person, I am the entire human race compacted.”