Glorious Victory?

Historic newspapers capture the growing conflict during the week of the First Battle of Bull Run.

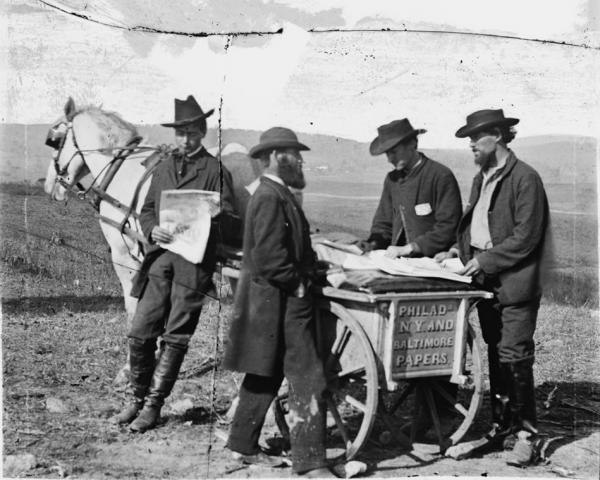

Newspaper vendor and cart in camp in Virginia, 1863

Credit: Library of Congress

Newspaper vendor and cart in camp in Virginia, 1863

Credit: Library of Congress

The National Republican newspaper in Washington trumpeted a Union victory one hundred and fifty years ago today.

“FROM THE SEAT OF WAR!” ran the first of 17 stacked headlines. “THE ENEMY OUTFLANKED!” “GLORIOUS VICTORY!”

In fact, the Union lost the first major land battle of the Civil War, later known as the First Battle of Bull Run. Newspapers had come a long way by 1861, but accuracy was a challenge when eyewitnesses could hardly tell Union soldiers from Confederates.

Historic newspapers — available online in the NEH-funded Chronicling America database — take the reader back to late July of 1861.

Soon after the battle, prisoners-of-war arrived in Washington. Eleven Confederate soldiers were marched through the streets of Washington to the Old Capitol Prison, according to the National Republican. Outside the Treasury, a crowd threatened to hang the Confederates, forcing guards to take the prisoners inside until the excitement died down. When they were led past the Willard Hotel, a bystander punched a prisoner, “nearly knocking him down.”

Wounded soldiers also came to Washington, leading the army to seek donations of ice, sheets, wine, “pure spirits,” and mosquito netting.

Farther afield, editors seemed to gnash their teeth at scant and conflicting reports. The Shreveport Daily News published the “gossip of Northern journals.” “The World says there is no truth in the reported fighting at Bull’s Run today,” runs one account in the Louisiana newspaper. Their sources ranged from War Department reports to “an intelligent and reliable gentleman.” Others proved less reliable. “Dispatches from St. Louis and other points are utterly useless,” runs one report on conflicts taking place in Missouri. “Private letters are equally so.”

Two weeks had passed before the weekly Independent in Oskaloosa, Kansas, reported “the latest news received by magnetic telegraph”— the “rebel battery” taken by Northern troops, a battle fought to a draw, and finally a “stampede” as Union soldiers retreated.

Newspapers captured other aspects of the growing conflict in July 1861. The “army haircut” was popular with Washington schoolboys, who drummed on their desks and hummed “our national airs.” A tailor was arrested for using seditious language in a New York boardinghouse, and in Mobile, Alabama, a runaway slave named Henry was captured in a swamp.

Meanwhile, the government announced plans to buy 400,000 blue flannel coats, 200,000 infantry caps, and 800,000 pairs of drawers. As the weeks passed, this list would grow: pickaxes, tent poles, drum sticks, worsted lace, bugles with extra mouthpieces.

As both sides prepared for the battles to come, the National Republican found a lesson in Bull Run: “If you have any doubt as to the supply of arms in the Southern army, there can be no doubt (judging from recent exploits) as to their supply of legs.”