In the early 1970s, John Korty was sent a batch of short stories written by famous American authors.

The San Francisco filmmaker was being asked to evaluate the tales as potential source material for a new series of short films. The American Short Story—as the NEH-supported series was called—would ultimately dramatize 17 of the most significant works of short fiction to spring from the pens of native-born writers. Airing on PBS in two seasons—the first in 1977, the second in 1980—the series was widely acclaimed in its day. The Christian Science Monitor, for example, described it as “one of American television’s most prestigious projects ever.”

“The stories reflect 100 years of examination of American values,” executive producer Robert Geller told HUMANITIES in 1977. “Our challenge has been to capture, on film, the perceptions, style, and narrative power of the author.”

When Geller first approached Korty, the series was still in its infancy. According to a 1979 press release announcing the second season, a 1973 grant of $92,000 funded the pilot, an adaptation of Ambrose Bierce’s “Parker Adderson, Philosopher.” Another grant covered an adaptation of Stephen Crane’s “The Blue Hotel,” plus Korty’s project. At the time, Korty’s credits were not extensive—highlights included an Academy Award-nominated documentary short, Breaking the Habit (1965), and a pair of experimental features, The Crazy-Quilt (1966) and Funnyman (1967)—but that didn’t stop him from being blunt in expressing his concerns about the proposed stories to Geller.

As Korty recalls: “I said, ‘Well, there’s no challenge to this. It’s supposed to be something new and different, and you’re just picking short stories that already look like they’re screenplays.’”

Seeking a more stimulating alternative, Korty remembered a thought-provoking tale he had once read: John Updike’s “The Music School.” First published in the New Yorker in 1964, the practically plotless story is made up entirely of the stream-of-consciousness digressions of a New Englander named Alfred Schweigen, whose mind wanders from the metaphysics of Holy Communion to the school where his daughter learns to play the piano. Two years later, the story was chosen as the centerpiece of Updike’s short story collection The Music School. But did the meandering, seemingly disjointed work have what it took to make a film—even a short one?

“Bob was actually quite reticent,” Korty comments. “Luckily, I was in a good bargaining position, because he really needed me to do something, and I said, ‘Well, sorry, Bob, but if you want a film from me, that’s going to be it’. . . . So much of what we read or look at, as soon as we get 10 percent into it, we sort of know how it’s going to end up, we know where it’s going, and I didn’t know that with the Updike story.”

Korty’s choice paid off. The film, starring Ron Weyand as Schweigen, was perhaps the most admired of the three pilot episodes that preceded the official launch of the series; NEH provided a $1,641,302 grant for the first season. Meanwhile, The Music School was honored at the San Francisco Film Festival, and Village Voice critics Andrew Sarris and Tom Allen compared it favorably with the original work: “The film is as felicitously articulated as Updike’s prose at its incisive best.” To this day, Korty says, he remains proud of the film, “because it wasn’t easy and it wasn’t something that other people might have done.”

Not all of the stories included in The American Short Story were as unlikely as The Music School, but several came close. The choices were made with the help of a scholarly committee, which included such notables as Matthew J. Bruccoli and Henry Nash Smith. The group evaluated about 100 stories culled from about 500 candidates, according to humanities. “We were after stories by established writers [and] stories that we thought represented those writers,” says Calvin Skaggs, who was a professor at Drew University before Geller hired him to work on the series, first as a script developer, then as a producer. “We had a Faulkner, we had a Hemingway, we had a Fitzgerald.”

The Music School notwithstanding, the dramatic prospects of a story had to be taken into account, as did what a 1977 article in the New York Times characterized as “practical considerations.” William Faulkner’s “Spotted Horses,” the Times reported, was omitted from the series due to the “impossibility of filming the crucial scene in which stampeding horses break down a house.” (Faulkner’s “Barn Burning,” however, was included.)

Yet, Skaggs says, “we made mistakes and we had surprises. “The Greatest Man in the World” is a very brief Thurber story, I think it’s five pages long—it’s a sketch—and yet we turned it into a film that I thought was quite funny and wonderful and crazy.” Especially difficult to dramatize, he adds, was the adaptation of Katherine Anne Porter’s “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall.” “That’s one of the hardest films I ever made because it all takes place in the imagination of a woman on the last day of her life.”

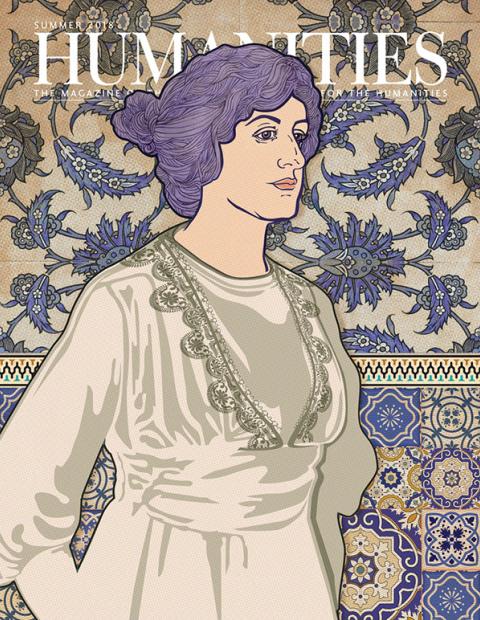

Improbable, too, was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” which made its debut in The Saturday Evening Post in 1920. The story takes as its subject the travails of a dull, gullible girl prodded on by her conniving cousin into altering her hairstyle on the pretext that it will render her more desirable to Warren, the young chap she has fallen for. “I can remember thinking: ‘Bernice’—ah, it’s a bit superficial,” Skaggs recalls, but after filmmaker Joan Micklin Silver was brought on to adapt the story, he had a change of heart. “It’s not like tragic Fitzgerald, but it’s like Jane Austen,” Skaggs says. “It’s funny and charming, but it’s also deep.”

Silver—who had won acclaim for her film Hester Street (1975), centered on Jewish immigrants who make their home in 1890s-era New York—was immediately drawn to “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” “They were indicating to me that they wanted me to do this,” Silver says. “I think I was the only woman director and this was the one that had a woman main character, so it seemed likely.” (In the series’ first season, Silver was indeed the only female director; in the second season, however, Randa Haines directed The Jilting of Granny Weatherall.) “I just thought it was wonderful,” Silver says. “It had its own world and I loved the characters.” Silver intended to take about two weeks to write the screenplay, but she found the work came easily and completed her work several days ahead of schedule. “I felt a little embarrassed,” she remembers. “I just pretended like I still had two more days to go, but I had actually finished it. It just all came very easily to me—the story, the way it was told. I loved the way Fitzgerald told the story.”

Indeed, Geller’s gambit throughout the series was to honor the way each of the represented authors told their stories. “Fidelity to the author,” the executive producer told HUMANITIES, “has been one of our main concerns.” To be sure, plenty of great films have strayed from their source material—Shakespeare would not recognize the masterful hash made of his plays by Orson Welles in Chimes at Midnight (1965)—but there is something to be said for films that respect their roots. “Hollywood buys a Faulkner story and then it has nothing to do with that novel or that story,” Skaggs comments. “That’s not always true, . . . but in this era, a long time ago when we were doing these, that was sort of the case. So, from the beginning, the [screenwriter] would be told by us: ‘We have to get the essence of this story.’” By and large, the filmmakers succeeded. Could Paul’s Case author Willa Cather have conceived of a more perfect Paul—the high-flown high school student in her story—than Eric Roberts in Lamont Johnson’s adaptation? With his slicked-back hair, eager eyes, and sudden outbursts of emotion, the actor is the very picture of the character.

Talented actors were routinely drawn to the series. As HUMANITIES noted in 1977, “It’s apparent that the prominent actors who auditioned for The American Short Story were attracted by the high caliber of scripts that resulted from the scholar/production consultations.” Several legends of the stage and screen were featured—Fritz Weaver starred in Henry James’s The Jolly Corner and Teresa Wright in Ring Lardner’s The Golden Honeymoon—but so were up-and-coming stars like Roberts; Ron Howard starred in Sherwood Anderson’s I’m a Fool, while Samuel L. Jackson made his first screen appearance of any note in Flannery O’Connor’s The Displaced Person. For the title part in Bernice Bobs Her Hair, Silver turned to Shelley Duvall, who had a string of memorable parts in Robert Altman films, including Thieves Like Us (1974) and Nashville (1975). “Hester Street was invited to the Telluride Film Festival, and my husband Ray [Silver] and I went, and as we walked into the festival, it seems to me, there was Shelley,” Silver recalls. “She just seemed to me like the perfect Bernice. She just had so many qualities that I thought would be excellent.”

Silver asked Duvall to round up some of her actor friends for a reading of the script. “She picked such wonderful actors, and they ended up in the movie,” Silver says. “It was like the casting director was also the star.” Bud Cort—Duvall’s slender, offbeat costar from Altman’s Brewster McCloud (1970)—won the part of Warren based on the reading. “I had thought that for her beau that I was going to pick somebody who was very Fitzgeraldy and tall and handsome and so on,” Silver comments, “but when Bud Cort read at her house when we were having this reading, I thought, ‘This is just a wonderful way to go.’”

The series was produced with an emphasis on economy. Budgets were low and schedules were short; according to Skaggs, no film took longer than two weeks to shoot. “We put the money on the screen,” Skaggs says. “We were tight-budgeted, tight-fisted, we didn’t waste, but we tried to do good work all along the way.” Despite boasting richly evocative 1920s-era sets, décor, and costumes, Bernice Bobs Her Hair was made for about $200,000, Skaggs says. HUMANITIES reported the filmmakers benefitted from the use of a period-accurate house whose owners lived in a motel during production—“every spoon, every bowl and room was intact.” Skaggs comments: “If you want to make a film on $200,000 . . . you have to be so perfect. You cannot just lag around. You can’t lose a day, because you’ve got to shoot it in nine days.”

Ironically, Korty’s choice of The Music School, and the tack he took in adapting it, provided a kind of rationale for the larger project of The American Short Story. As Updike’s story opens, Alfred Schweigen is preoccupied with a local priest’s edict for his flock to actually chew, rather than allow to melt in their mouths, the wafer dispensed during Communion. “The word is eat, and to dissolve the word is to dilute the transubstantiated metaphor of physical nourishment,” Schweigen narrates, referring to Christ’s instruction to “Take, eat.” He proceeds to link this tangent with an unrelated anecdote about an acquaintance who lost his life after a bullet blasted through his kitchen window. Schweigen strains to connect the Communion decree and this act of violence, but finally finds a point of contact. As Updike writes: “There is a parallel movement, a flight immaculately direct and elegant, from an immaterial phenomenon (an exegetical nicety, a maniac hatred) to a material one (a bulky wafer, a bullet in the temple).”

Korty’s screenplay adheres closely to Updike’s story: “Because I liked Updike’s language so much,” the filmmaker says, “and I regard him as a real master writer, I didn’t feel it was up to me to try to outdo him and write something else.”

Similarly, The American Short Story made tangible that which could otherwise only be imagined. On the page characters, places, and incidents exist in the mind’s eye, but on the screen they are shown and heard. There is a pleasingly concrete quality to the films in the series—think of the sharp snap of the scissors as Bernice pays back her cousin by pruning her braided hair, or the snoring of a somnolent security guard while Paul sits mesmerized by works of art that adorn a concert-hall lobby. The immaterial becomes thrillingly material in such moments.

In The Music School, Korty finds a metaphor in the medium of film itself for Updike’s idea about the passage from the ethereal to the physical. Serving as his own cinematographer, Korty lends his images the heaviness of reality—a gush of water on the face of our hero or the spilled milk that follows his acquaintance’s murder. In one striking section, Korty uses documentary material he shot of actual nuns making Communion wafers while Schweigen comments on the soundtrack about the matter of chewing versus melting. We see the batter and the baked product punched into slivers; there is nothing mysterious about the process, nor was there about the nuns themselves. “Even the most modest and straitlaced people, if they get a chance, would love to be in a movie,” Korty remembers. “They were clearly kind of flattered and excited to be in a movie. . . . I’d been there a couple hours, and I started to pack up, and there was a nun at the end of the assembly line who looked at me [with] this terrible, sad face and she said, ‘Are you leaving?’ Because I hadn’t photographed her yet.”

In the film’s haunting conclusion, just before Schweigen concludes that “the world is the host; it must be chewed,” the camera catches a glimpse of a wooden banister railing in the music school—the thick, sturdy piece of wood is illuminated by a shaft of blinding late afternoon sunlight. No words, not even those by Updike, can compete with the solidity of the wood and the brilliance of the light. “I just thought that was a wonderful way of ending it up—taking something as theoretical as Communion and saying, ‘The world is the host,’” Korty reflects. “A lot of what I try to do in my films is to have a tactile feeling to connect the abstraction of a film on a screen to something that people can feel with their fingers.”

“Ecstatic” is the word Skaggs uses to describe the reception to the first season of The American Short Story when it aired on PBS. “The press loved it,” he says. “PBS loved it. The Brits loved these stories.” According to New York Times television critic John J. O’Connor, who singled out the first season as one of the small-screen highlights of 1977, the episodes were “the first public-TV presentation ever to be purchased by the British Broadcasting Corporation.” Skaggs adds: “It was on the basis of that wide acceptance and approval that we got the second grant.”

For the second season, NEH provided $1,350,000, which was combined with $600,000 from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and $650,000 from the Xerox Corporation, according to the 1979 press release. “NEH’s continuing support for this outstanding series of films reflects the Endowment’s commitment to broad access to the treasures and riches of American literature, history and culture,” said then Chairman Joseph D. Duffey.

The series’ reach went beyond living rooms and into classrooms—“For at least a decade or so after they were made, every school child . . . saw Bernice Bobs Her Hair in school,” Skaggs says. “The schools bought them”—yet nothing about the films call to mind homework. Perhaps that is because they ask nothing more of a viewer than the original stories do of a reader: a clear mind, an open heart, a bit of time in order to be swept away. Strikingly, the lengths of the episodes vary widely: The Music School clocks in at 30 minutes, while Bernice Bobs Her Hair runs for 45 minutes. Skaggs observes: “A classic short story really has the setup, the epiphany, and the end, and it’s just perfect for short films.” Adds Korty: “A lot of films that you see in theaters have really been expanded beyond the length that they can justify.”

The magic of The American Short Story remains fresh; today, most episodes can be purchased on DVD. “There’s a purity to them that you don’t see very often on the screen—on your television screen or in a movie theater or on your phone,” reflects Skaggs, who acknowledges the series’ debt to NEH. “They gave what was for us a huge amount of money then. They had real faith.” The series helped prove that short stories can be read; but, as Updike might put it, they can also be chewed.