In an interview with HUMANITIES magazine, NEH Chairman Jon Parrish Peede talks about his childhood ambition to become a doctor and what got in the way: a growing love of poetry and the difficulty of upper-level science courses. He also discusses his Southern heritage and his interest, as a scholar and a collector, in American women authors in wartime. Having worked as an editor and a grantmaker, Peede brings a wealth of practical experience to the job of selecting humanities projects for support.

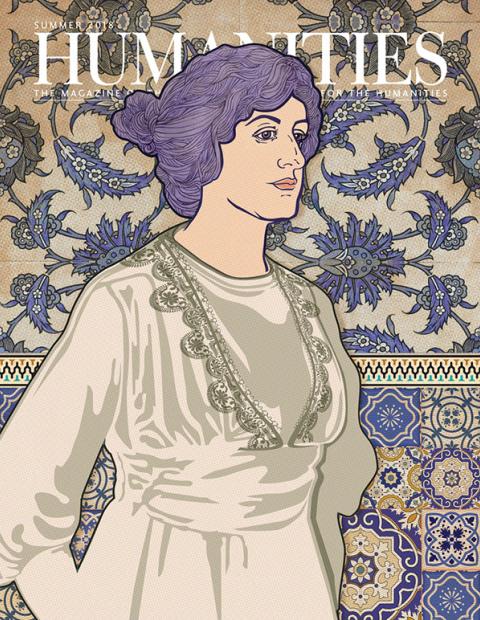

Edith Wharton is certainly an American author who wrote during wartime. Living in Paris in 1917, she kept up with her literary and journalistic commitments even as she worked to help people displaced by the fighting. When the opportunity arose to take a vacation from the war and see French Morocco, she packed her bags and headed south. As Meredith Hindley explains, it was an extraordinary voyage, for an extraordinary writer, at an extraordinary time.

W. H. Auden, too, wrote about war, quite memorably, in poems such as “September 1, 1939” and “Refugee Blues,” but his greatest subject may have been death. As I flip through a copy of Selected Poems after reading Danny Heitman’s essay on this shabbily dressed bard, I am struck by how many of his poems are requiem pieces—for Yeats, for a tyrant, for the “Unknown Citizen,” and most of all, “Funeral Blues,” with which Heitman begins. Yet to read Auden is, as Heitman explains, somehow life-affirming.

The American Precision Museum in the little town of Windsor shows how manufacturers found inspiration in war, as government contracts for rifles helped accelerate the industrial revolution as it played out in the factories of Vermont and New England. Sarah Stewart Taylor explores the permanent exhibition at this NEH-supported museum, where a tour of historic lathes and cutting machines helps us understand the machines that only machines can make.

“To promote the humanities” has always been a fundamental part of the mission of NEH. In the 1970s, this notion inspired a project to bring some of the greatest short stories written by American authors to the small screen through dramatizations involving some of the best young actors and directors working at the time. Peter Tonguette looks back at a project that won popular approval and critical acclaim.

For the record, I incorrectly stated in my last editor’s note that Frederick Douglass escaped slavery from a Maryland plantation, when, in fact, his last days as a slave took place in Baltimore, where he was hired out as a caulker in the shipbuilding industry. To get my facts straight, I reviewed several chapters in Douglass’s autobiography, and was reminded of how artfully he avoided stating the exact details of his escape, lest doing so make it harder for other slaves to run away to freedom.