South Dakota | The temperature reads minus 7 on a weekday morning in January. Snowflakes whip along the ground without sticking and spin upward into little funnels before scattering. The sky appears beautiful and iconic through the car window, but once you step outside the weather is literally in your face. As you dash across the parking lot, the cold finds your pores and a shrill wind blows straight into your bones.

Inside a handsome former library at the state university in Brookings, people gather in a lecture room to hear from a visiting trio of speakers. About half the audience consists of faculty or town residents. A music teacher talks quietly to his class about where to meet the next afternoon for the bus ride to Sioux Falls. He reminds the students to dress appropriately for the concert.

Standing in front, Delta David Gier, the conductor and musical director of the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra, begins the discussion. Dressed in black and gray, he is tall and Nordic-looking with a longish forehead framed by the suggestion of a center part and a blondish hairline of graying curls. He starts by asking everyone to reimagine an orchestra as a humanities institution—one that brings together symphonic music and the immersive intellectual context you get from a museum. That, he says, is what is going on here, in this room, and tomorrow on stage in the program called “Music Unwound: Aaron Copland and Mexico.” It’s a cross-breeding of classical music and humanistic inquiry.

The next person to speak is Lorenzo Candelaria, who goes by Frank. He personifies the institutional ties that, under the right circumstances, might develop between a university and an orchestra. An associate provost at the University of Texas at El Paso, he is a scholar of the Catholic music cultures of Spain and Mexico, a trained violinist, and a board member of the El Paso Symphony Orchestra. Over the next 40 minutes he delivers a brief history of Mexico.

Candelaria, who is Mexican American and a seasoned instructor, knows how to keep the material moving. His goal is not to dwell on the Aztec language Nahuatl or the Aztec use of music in rituals involving human sacrifice, both of which he mentions. Instead, he wants to highlight a moment in the twentieth century when many Mexican artists were searching their country’s past for ideas on where Mexican art should go.

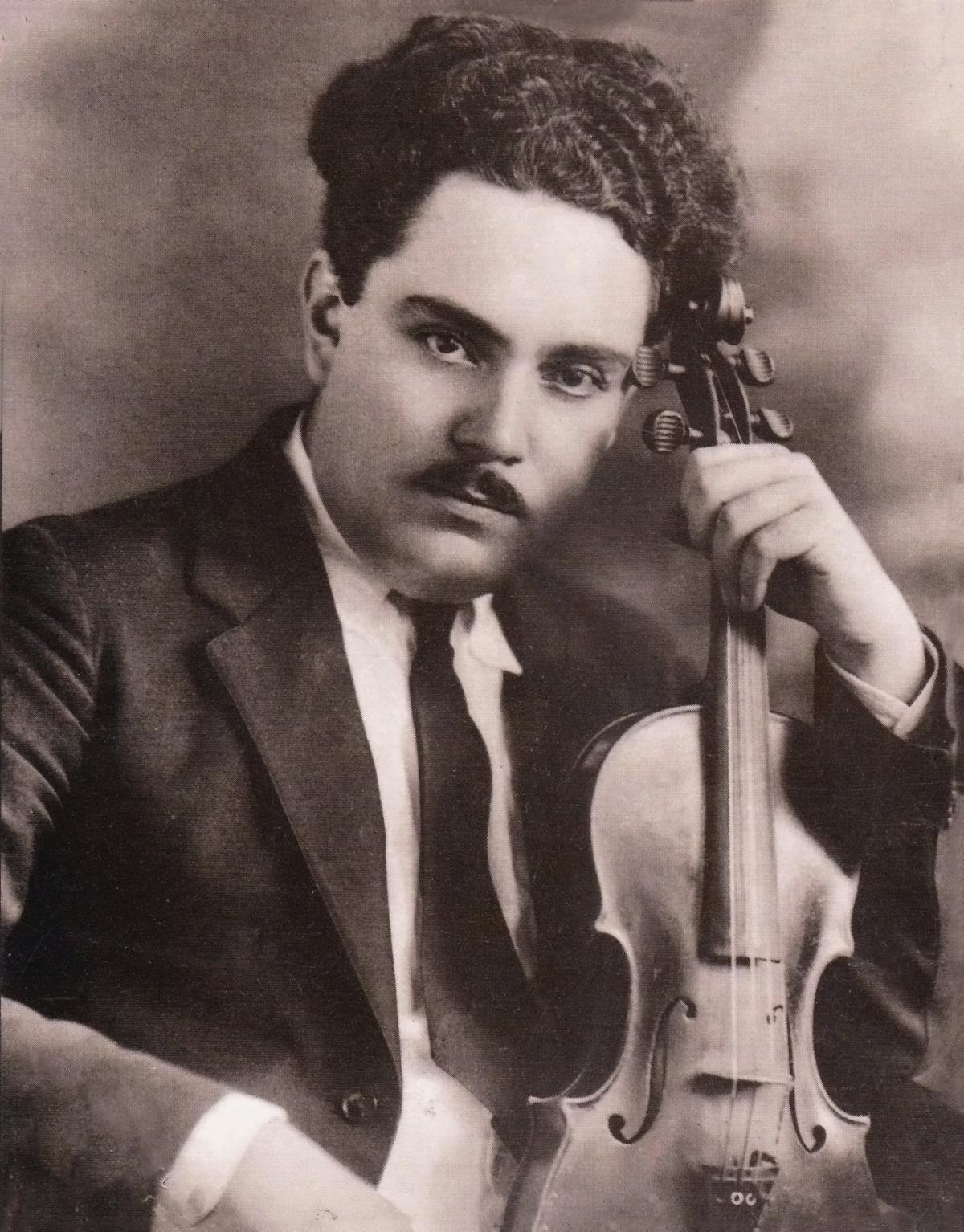

“How many people here have ever heard of Silvestre Revueltas?”

A couple hands stir, but none are raised with any confidence.

Candelaria, in a jacket, tie, and an artful rooster’s peak of black hair, demonstrates how to pronounce the composer’s name, one syllable at a time—SIL-vest-ray Re-VWELL-tas—which the room dutifully repeats in a Midwestern accent.

Revueltas is the Mexico in “Copland and Mexico.” His propulsive, hard-to-categorize music should be better known than it is, say his enthusiastic fans. The music critic Alex Ross has called him “a giant talent” with “a wildly inventive and laceratingly sharp musical mind.”

Candelaria talks about postrevolutionary Mexico in the 1930s, when Diego Rivera was at the height of his fame and Mexican artists were looking to folk culture and an Aztec past for a richer sense of historical identity. Slides flash on the video screen at the front of the room, showing paintings by Rufino Tamayo and the muralist José Clemente Orozco. Candelaria reads the poem by Cuban writer Nicolás Guillén that inspired Revueltas’s composition, Sensemayá, once again putting the audience to work. In unison, they repeat a sacrificial chant at the beginning of the poem, which is about killing a snake.

The snake is particularly significant, says Candelaria, as it harkens back to pre-Columbian culture and connects forward to the image at the center of the present-day Mexican flag—something for the crowd to consider as the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra performs Sensemayá this weekend.

This lecture is not just an appetizer for the concert, it is part of the entrée. These lessons in the Mexican Revolution, the introduction to a symphonic composer whose gritty material comes from his own life and times, and the reflections on the search for a usable past, all of this material is intended to engage the audience in a certain way: to make them think about the music. It is also an invitation to these students and this college, not simply to attend a concert but to build a larger relationship with an orchestra, to be a partner in its programming.

The last speaker is the Music Unwound project director Joseph Horowitz, the oldest of the three men. He wears glasses and his face is fringed with a fluffy gray beard that gives him a professorial air. He is an accomplished music writer and historian, the author of Classical Music in America, Understanding Toscanini, and several other well-regarded books. For several years in the 1990s, he was the executive director of the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra, then in residence at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where he first experimented with humanities-infused music concerts.

Horowitz brings a very different energy, hangdog, brainy, and a little hard to predict. He decides, seemingly on the spot, not to talk about Revueltas, Aaron Copland, and this weekend’s program, but about Music Unwound’s plans for next year.

Sitting down at a piano, he plays a bit of music from memory and asks the audience to identify the composer. It sounds American. George Gershwin, says one person. A good guess but incorrect, says Horowitz. Then he plays another tune, this one older-sounding and jumpier, like a piece by Scott Joplin, whose name someone calls out. Another good guess, says Horowitz, but also wrong.

“Dvořák?” asks an older woman in the back.

Horowitz is visibly pleased, and quick to congratulate the guesser. He begins talking about “American Roots,” the theme for next year’s Music Unwound program, touching on a body of music he has explored on stage and in writing: African-American spirituals.

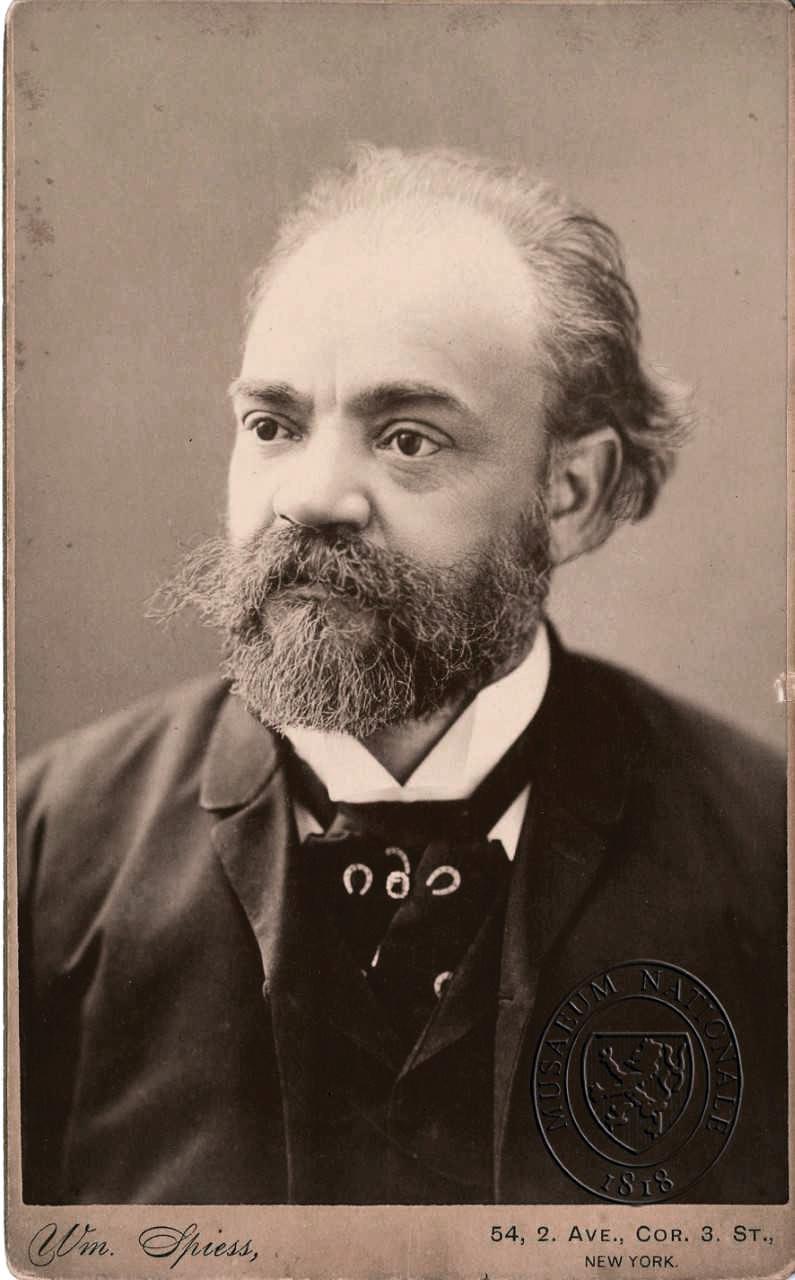

“I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called the Negro melodies,” Horowitz says, quoting Dvořák.

During a long stay in the United States in the 1890s, Antonín Dvořák looked to plantation songs for the beginnings of an American musical idiom, just as he had looked to Bohemian folk music for the compositions that had made him famous throughout Europe. At the National Conservatory of Music near New York’s Union Square, where Dvořák was hired as director, he made the young African-American singer Harry Burleigh his assistant. What Dvořák then developed in the New World Symphony and other music included quotations and variations and riffs of an American style that, Horowitz says, sounded like Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess before the fact.

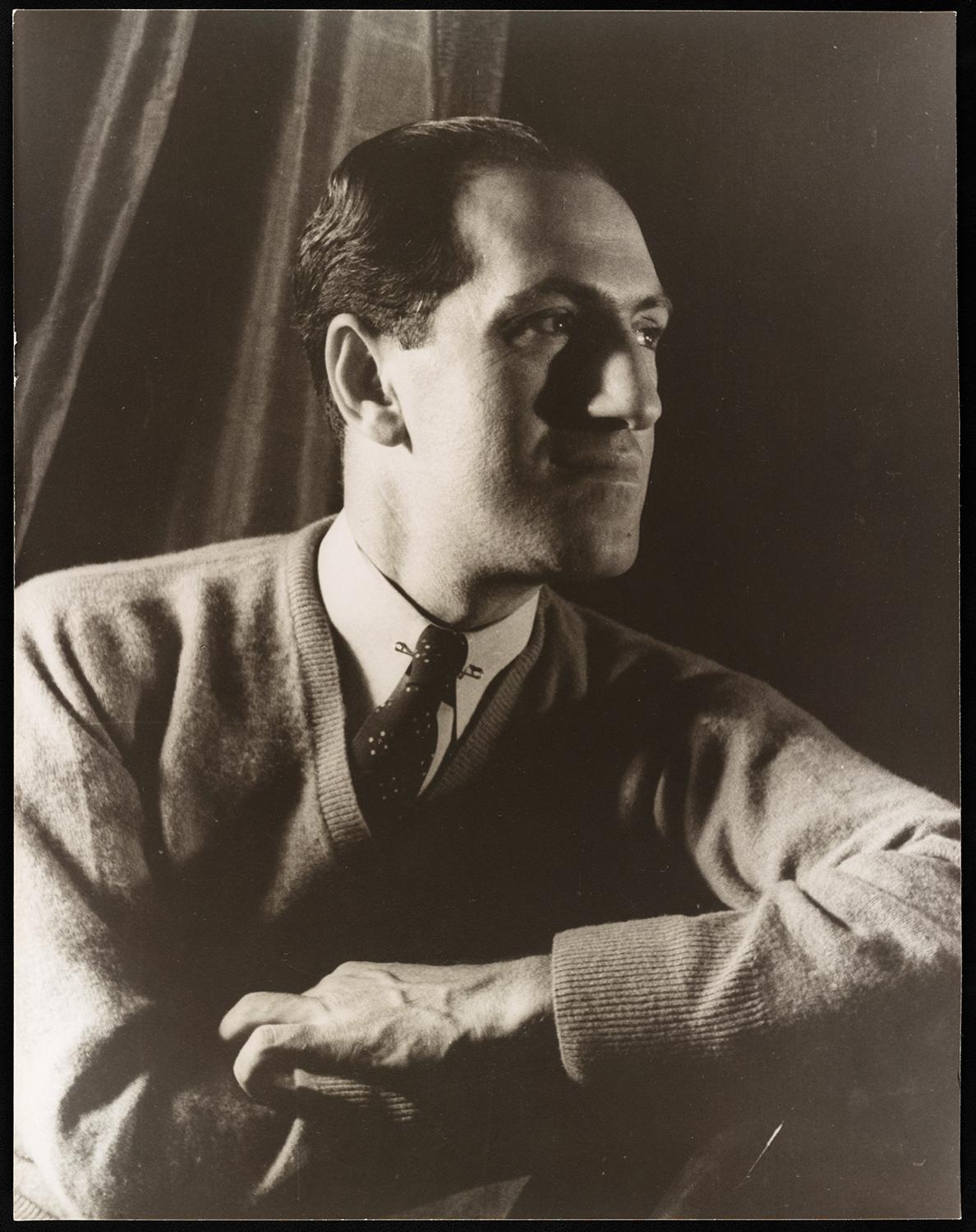

Dvořák, Revueltas, and Gershwin are all good guys in Horowitz’s book (or, rather, books, I should say, because he has written many) for the reason that each sought an authentic source for the music they created. Though composing music in a European genre, Revueltas and Gershwin looked to their native cultures for raw materials.

Revueltas listened carefully to the mariachi bands that played in the park and thought deeply about the sounds of everyday life in Mexico. He fulminated against the European masters and claimed to be cleaning out “the old Conservatory that was crumbling down with tradition, moths, and glorious sadness.” Gershwin visited black churches, learned about Gullah culture, and soaked up jazz and ragtime. Their work was less polished and seemingly less finished than some others’, says Horowitz, but the music itself, borne aloft by the historical power behind it, was more genuine.

And so what if Gershwin and Revueltas seem less finished? Horowitz asks. The “unfinished” composers, he says, “are going to end up on top.” Gershwin over Copland. Revueltas over his contemporary Carlos Chávez. And Charles Ives, the neglected American composer, too, Horowitz thinks will come out a winner.

“Being unfinished is a classic American artistic trope,” he says. “America itself is unfinished. We’ll never escape the legacy of slavery.”

This is what it’s like to hang out with Horowitz, by the way. One moment you’re wondering who Charles Ives is, and the next moment he’s talking about the central moral dilemma of American history.

”You can’t talk about music in America without talking about race,” he says.

According to Horowitz’s larger argument, a great wrong turn for classical music in America came when it abandoned the musical tradition found among African-American slaves and their descendants. “Classical music,” he says, “remained white,” and thus lost its connection to a musical idiom that could have fueled something different, something distinctly American, and truly exceptional.

Horowitz explores this idea at length in a book he is writing called Using the Past—A Meditation on Race and Culture, Reminiscence and Denial. He asks the reader to consider, for instance, what the black vernacular did for jazz. And to consider what it did for the American novel, beginning with Huckleberry Finn. (One can, of course, add what it did for pop music.)

Horowitz cites the authority of W.E.B. du Bois, who wrote in 1903 that “the Negro folk-song—the rhythmic cry of the slave—stands today not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side of the seas.”

His argument, however, puts Horowitz at odds with white admirers of classical music who like it the way it is and today’s critics of cultural appropriation as well. But, he says, “appropriating is what composers do.” Take Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess: Some critics fault it for racial stereotypes; Horowitz calls it the “supreme creative achievement” of classical music in America.

Not that there hasn’t been other music in the United States besides African-American music. Horowitz is himself an admirer of many American composers from Charles Ives to Steve Reich today. And he is especially interested in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when you could still find conductors who were taste leaders working on behalf of living, breathing composers, and when orchestras were prized by their communities: the golden age before World War I, when the Boston Symphony Orchestra was more popular than the Red Sox.

Today, however, the vital signs of classical music all tend in the wrong direction, says Horowitz. The conductors fly in and leave. The musicianship is superior but dull. The composer is long dead, and, on stage and off, people know little about him anyway. The shrinking audience only wants to hear the most pedigreed and canonical of music. The orchestra is not a tastemaker; it’s a follower. Marketing and fund-raising efforts predominate. The financials drive everything, and everything is expensive: the musicians, the guest soloists, the fly-by conductors, the tickets.

Horowitz complains a lot, and one of his bigger, more enveloping criticisms is what brings him to the humanities. “Orchestras are not interested in their own history,” he says. “They are not curators of the past.” This is the moment when Horowitz is most likely to smile his brokenhearted, I-can’t-help-it, I-have-to-tell-the-truth smile. As smiles go, it is remarkably sad.

Theater companies, he points out, have dramaturges. Museums are staffed by scholars. But orchestras, despite their reverence for great music of the past, don’t even care about their own backstories, says Horowitz.

“They’re happy to do coffee table books because they can sell them in their gift shops. . . . But will they underwrite a serious institutional history? No.”

A month earlier, I had asked Horowitz on the phone if there was somewhere less cold than South Dakota in January that I might be able to see his program, Music Unwound, which has been performed with a dozen different orchestras across the country. Yes, he said, there was, but I should come to South Dakota anyway because the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra is “in some ways the most innovative orchestra in the United States.” It is, he said, “transformed.”

My next question was, Transformed into what?

In 2003, the orchestra hired a new conductor and music director. In the right hands, its board believed, SDSO could prove that it was more than just a solid regional orchestra. Delta David Gier, then assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic, took the job and moved to Sioux Falls, joining the community he intended to serve.

Gier came with an agenda, primarily musical. He initiated a project to perform compositions by Pulitzer Prize winners, forging a link with living composers that Terry Teachout in the Wall Street Journal hailed as “an unprecedented programming innovation.” A great lover of Gustav Mahler, Gier also decided that SDSO would perform the full cycle of Mahler’s symphonies as a bar-raising exercise to improve the level of performance.

Although an advocate of new music, Gier is also a great believer in the standard ideal for an orchestra: performing, as well as humanly possible, a finite set of classic works hailing from a two- to three-hundred-year period of European history. But it is not the only ideal to which he subscribes. Gier also thinks orchestras should look to broaden their audiences beyond the usual crowd of subscription holders and wealthy board members. He believes an orchestra should belong to the whole community.

At a cocktail party during his first year in Sioux Falls he approached a woman he knew to be managing the city’s programming for Martin Luther King Day. He wanted to talk about partnering and outreach to African Americans in Sioux Falls and was surprised by her response. Polite but discouraging, she told him that the community that really needed reaching out to wasn’t the black community. It was Native Americans.

So began the Lakota Music Project. The way Gier tells it, the orchestra hosted a lunch for Native American leaders from the Sioux Falls area, and the reaction to his pitch was distrustful and even dismissive. Gier said outreach, and his guests heard exploitation. They wondered openly who was going to pay for his little program and, moreover, who was going to make money off it. But Gier made one friend that day, a tribal affairs consultant named Barry LeBeau, who thought, “This guy is nuts, but this is going to be a lot of fun.”

In the next four years, Gier accompanied LeBeau to meetings across the state. He learned all kinds of things, for example, that “you don’t get people together on the rez without food.” And it should be their food, not yours: “A nice stew and some fried bread,” is what LeBeau said they needed. Gier also learned not to go around telling Native Americans what he wanted to do for them. Instead, he needed to ask what they should do together.

“That’s when I realized this whole engagement thing was about listening,” says Gier, “not building programs that I thought would be helpful.”

Finally, in May of 2009, the hard work paid off. The South Dakota Symphony Orchestra performed with Native-American musicians on three reservations and in two other South Dakota communities. The collaborative program included original compositions by Native and non-Native composers, presented in a historically informed context, and has now been performed more than 30 times. It also helped SDSO win the coveted Bush Prize for Community Innovation.

Anyone familiar with orchestras is likely to ask, What did the musicians think of all this? Did they balk at sharing a stage with nonclassical music? Did they complain about the hours spent on buses, touring the state? Not that I heard. In fact, the handful I spoke to were all quick to raise the subject and were enthusiastic, echoing what the SDSO violinist Magdalena Modzelewska told a reporter in 2009, “You feel the greatness of the moment, its importance. And it’s wonderful, it really is wonderful.”

In 2016, the Lakota Music Project worked with Horowitz’s Music Unwound program. Ronnie Theisz, professor emeritus of English and Indian Studies at Black Hills State University, participated, discussing on stage the rhythm structure and vocal techniques of Native-American music and reviewing how Native Americans had been understood as “noble savages” in the nineteenth century and their culture later reconceived as Indianist kitsch. Chris Eagle Hawk of the Oglala Lakota Tribe contributed remarks on the role of music in Lakota culture and the sacredness of the Black Hills. Music Unwound, being a multimedia program, also used imagery to draw out, for example, the connections between Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha” and Dvořák’s Largo from the New World Symphony.

New and old music together, all of it set in a rich historical context, and staged for a specific but heterogeneous audience of young and old, Indian and non-Indian: This is what Horowitz meant by “transformed.”

On Saturday night, I get to see “Copland and Mexico,” which has been performed before in El Paso, Texas, through the leadership of Frank Candelaria and a collaboration involving the University of Texas at El Paso and the El Paso Orchestra. It has also been performed in Las Vegas with the Las Vegas Philharmonic Orchestra. The program is a loose script of musical pieces and spoken material, some of it expositional and some of it dramatic. Letters, poetry, and even Copland’s 1953 testimony before Congress are all built into the presentation.

Again, outreach is a major part of the proceedings. South Dakota Symphony Orchestra recently hired a full-time engagement coordinator named Kristy Kayser to perform the day-to-day house calls and handshakes that keep South Dakotans at the center of the orchestra’s plans. Working with local schools, community centers, business groups, and churches, she has cast a wide net to invite the Latino community of Sioux Falls to the 1,900-seat Washington Pavilion.

Students from two local middle schools have produced infographics about Mexico: its population, economy, crime (a surprising number of students looked into this one), history, and culture. These are on display in lobbies around the pavilion. Maestro Gier interviews two of the students on stage before the performance. In all, the orchestra gave away enough vouchers to draw 374 people in addition to the evening’s paying customers for an almost full house.

All this community development may sound incompatible with an intellectually adventurous, idea-driven evening of musical discovery, but, apparently, it is not.

The performance of Copland is confident, shimmering, and upbeat. The slacker parts of El Salón México recall Gier’s instructions during rehearsal that these should sound a little bit light-headed, inebriated even, but pleasantly so. Primed for yet another evening of classical music, the audience is being lulled into a false sense of security.

“Copland deserves to be more controversial than he is,” Horowitz had told me.

Gier and Candelaria also take a dim view of Copland. “Perpetually confused,” Gier called him. “El Salón México,” says Candelaria, “sounds like what a tourist thinks Mexican music sounds like.” Horowitz views Copland as a “synthetic populist,” someone who, “as a modernist, wasn’t really comfortable with the vernacular.” The beef against Copland was so strong that I was almost relieved when, over drinks, SDSO’s assistant conductor spoke up for Appalachian Spring, calling it a masterpiece.

Copland’s flirtation with the Communists has not hurt his standing as the quintessential American composer, perhaps because no one thinks it was a true affair of the heart and because it took place in the desperate 1930s when communism appeared to many people, along with fascism and Nazism, as just another flavor on the menu of post-democratic scenarios. Also, Copland was a confirmed poet of the American story, as in the ballet Rodeo, complete with cowboys and a hoedown, selections of which open the Music Unwound program.

But if the historical record shows something less than a serious political conversion, it left behind one rather damning piece of evidence, which “Copland and Mexico” highlights. In 1934, New Masses, a magazine of the Communist party, sponsored a contest for music to accompany a poem called “Into the Streets May First.” Copland wrote a piece of music, entered it, and won the contest. New Masses praised his song for its style and vitality, commenting that “some of the intervals may be somewhat difficult upon a first hearing or singing, but we believe the ear will readily accustom itself to their sound.”

On stage, as Gier and Candelaria discuss the place of Mexico in the life and music of Copland, they are interrupted by a trio of sign-carrying protestors who burst on stage, singing Copland’s prizewinning Communist anthem. The orchestra helps fill out the vocals because plans to work with an actual choir had fallen through.

An actor playing Copland then takes a spotlight at center stage and delivers his 1953 testimony from a hearing with Senator McCarthy and attorney Roy Cohn, both played by offstage voices. The composer denies any association with the Communist party, sounding rather weaselly as he says, “Not that I can recall,” “Not to my knowledge,” and so on.

Copland disavowed the music for “Into the Streets May First,” calling it the “silliest thing I ever did.” And Joseph McCarthy, of course, soon had his comeuppance at the famous Army hearings.

The second half of the program—and, musically, the night—belongs to Revueltas. “You have to choose,” says Horowitz, even if the program itself is proof that you don’t. It is, though, the unstated goal of Horowitz and company to make the case for Revueltas as a great composer. In a kind of mirroring of the Copland first act, Revueltas’s politics are on display.

After Sensemayá, introduced by a superbly disruptive, almost noirish, piece of symphonic rebellion, the orchestra plays the composer’s tribute to Federico García Lorca that by itself makes a very convincing case for Revueltas’s depth of sensibility.

Next up is a performance of Revueltas’s score for the 1936 film Redes, a gorgeous black-and-white morality tale about fishermen and political corruption shot by the cinematographer Paul Strand, which is screened as the orchestra plays. The music is not one of those mincing little scores one hears whispered in the background of some Hollywood films, but a bold work of art in its own right. Revueltas was not shy about his contribution, believing the film (which, like Revueltas himself, was never quite finished) should be cut to fit the music and not the other way around.

Lacking a time-coded copy of the film, Gier has had to memorize each scene to make sure the orchestra is keeping pace. Over Christmas, his relatives were raising their eyebrows as he watched and rewatched this obscure old foreign-language film about fishermen, everyone thinking the same thought: Isn’t there an easier way to do this?

The hard work pays off as the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra follows the fishing boats over each swell of ocean wave and annotates the film’s pivotal funeral scene. A child has died because of the cruelty of a system that benefits the rich and fails to protect the innocent, and the simple ritual of a burial in a small Mexican community achieves a massive pathos thanks to Strand’s cinematography and Revueltas’s sonic framing.

Live-scoring is a weird kind of race between musicians and movie screen. Whenever the orchestra hits its marks, the effect is riveting. The knowledge that this live experience can’t be had at home on the couch helps ramp up the drama. Having listened to the orchestra practice some of this score, I realize how difficult it’s going to be for them to finish on time, and am taken aback when they find a way to synchronize the very last notes almost perfectly with the close of the film’s final scene.

Afterward, when I see Gier, he is smiling but spent. After so many hours on the go this week, talking to students, doing radio interviews, running rehearsals, standing on the podium before one and all as the musician in charge, he is tired, and practically hiding in a seat next to his wife in the back of a restaurant across the street from the Washington Pavilion. And yet he has a matinee to conduct tomorrow. Candelaria, whose reading of the Sensemayá poem and other Revueltas-related text was especially fine, seems totally at ease. Horowitz is jubilant and even more talkative than usual.

We talk about spirituality. Horowitz is a secular Jew. Music, he tells me, filled the space that others reserve for religion. Like many believers, Horowitz is conflicted in his faith. There is something paradoxical, he says, about being an American in the Eurocentric world of classical music.

There is also something paradoxical about being Joseph Horowitz: In a cultural scene where the jury’s already in, he is reexamining the evidence. He is reopening the case, asking a lot of old questions like, Why isn’t there an American Mozart? And, When did all this become so settled and institutionalized and expensive? In a milieu full of listeners, he is a born arguer.

Not that he doesn’t listen. In fact, he is a very sensitive listener as shown by countless examples in his vast output of writing, but I have come to think that Horowitz should make a one-man show of his thoughts on classical music and life. He’s an inspired monologist—or, as he puts it, “I have a big mouth”—and it would be very interesting and not a little bit shocking to have him airing his many opinions in a stand-up format. A brilliant historian, a freethinker, a music programmer, he is really one of a kind.