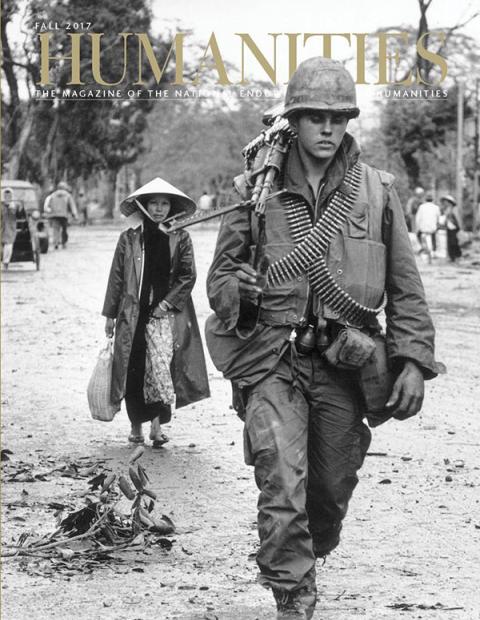

The Vietnam War, a new 10-part film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, debuted on PBS on September 17. The 18-hour documentary examines the war from the American and Vietnamese perspectives, mapping its bloody, tumultuous, and often controversial course. The story unfurls through the eyes of the war’s participants, as 80 people, from soldiers to nurses to politicians to antiwar protestors, share their experiences. The interviews, which are often full of pain, disbelief, and remorse, give the film its emotional core. Meredith Hindley of Humanities spoke by telephone with codirector and producer Lynn Novick and producer Sarah Botstein about how they researched and conducted the interviews that are integral to the documentary.

MEREDITH HINDLEY: How do you find people to interview?

SARAH BOTSTEIN: That is always one of our favorite questions to answer, but there is no one way we find people is really the truth. We interviewed 100 people, 80 of whom are in the film. For each person who is on camera, we talk to or meet with at least 10, 12, 15 others. We talk with a lot of people, we meet with a lot of people, then we think long and hard about the kinds of people we want.

For Vietnam, we worked very closely with our board of advisers. We read a lot of books. We did research, and then we backtracked from there. George Wickes, for example, who was the first interview we did for the series, was an OSS officer who was in Vietnam after World War II. If you are doing research about that period of the war, you find him. And then, if you figure out that he is still alive and he is as old as he is, you get on a plane.

HINDLEY: Once you’ve identified someone, what happens next?

BOTSTEIN: We would typically write a letter and/or call and introduce ourselves, set up a time to talk with that person, usually on the phone first, because the likelihood that they are near us is small. We spend some time talking with them on the phone, get a sense of their personality, the way they talk about their life. Then we do some real homework about where they were and when. If it is applicable, we check out their military records.

Then we go meet with them and get a sense of what they are like in person and delve even more deeply into their experiences. After that we circle back with our team. The four of us, Lynn, Ken Burns, Geoff Ward, who is our writer, and I are deciding who to interview as we go. We usually meet the person once or twice without a camera.

HINDLEY: What role do referrals play in finding people?

LYNN NOVICK: We were very lucky that we got to know Joe Galloway, who was a reporter who covered the war at a very seminal moment in 1965, and off and on for the rest of the time. He was very well connected and knew a lot of people who also had been involved or touched by the war in different ways. He agreed to be interviewed and be an adviser. And then he recommended others. And some of those people recommended other people.

That’s how we found the Crockers. We wanted to find a Gold Star family. We didn't feel we could represent the tragedy of the war without talking to people who had lost somebody in the war. But there are 58,000 names on the Wall, so where do you start?

We started by speaking with the people at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, asking if they knew of any Gold Star mothers. They did not have any ideas off the top of their head. We went next to the Library of Congress’s Veterans History Project, which is a repository of oral histories from veterans of any war. The curator said, “You know, there was a family that came in not too long ago. The husband was depositing his World War II oral history, and the wife left a memoir that she had written but hadn't been published about their experiences with their son, who died in Vietnam, and she is still alive, and maybe she would talk with you.”

The document that Mrs. Crocker had written helped us walk through her son's life before the war, and learn about their family. It was an extraordinary portrait of a mother coming to terms with the loss of a child in a war. We knew enough to stop looking when we found the Crockers.

Sarah and I spent a day with her before we had any cameras, explaining who we were, what we wanted to do. What we were asking, you can't ask over the phone.

She was really more than enthusiastic about doing it. I think it was a chance to honor her son's memory, and, as she said, maybe help other families who are also grieving.

Then after that, we were able to prevail upon her daughter, Carol, to also do an interview and hear about the same event from a totally different perspective, which was really extraordinary.

HINDLEY: What makes someone a good interview on camera?

NOVICK: There is a certain amount of charisma and being an organized thinker and telling your story in a coherent way.

But there is also something that you can't really describe, some je ne sais quoi about what makes somebody jump off a television screen that over the years we have learned intuitively. I think it is kind of an authenticity: genuine, and honest, and direct.

We do not want to interview someone if we don't think they're going to be able to tell their story well with the camera on, because that is not fair to them. We try not to put somebody through that unless we think there is a very, very good chance that we are going to use the material.

HINDLEY: Do you think spending time with someone before you interview them on film helps build a sense of trust and intimacy?

NOVICK: I absolutely do, for a story like this.

HINDLEY: You are not just starting the conversation fresh.

NOVICK: What we try to do is have some separation between the time we spend with them and then the actual interview. It could be weeks or months in between, so that it doesn't feel like, "Oh, I just told you that thing, and now I am telling it to you again."

We take notes when we are meeting with people ahead of time, so we remember to ask about things that are important to them. Also things that we want to follow up on when we actually do the interview.

HINDLEY: It looked like most of the interviews were filmed in their homes.

BOTSTEIN: Most of them. Whenever we can, we interview someone in their home.

HINDLEY: Why that venue?

BOTSTEIN: Because it is important. They are comfortable there. It is convenient for them. They are sometimes older. It is nice to film someone in their natural environment.

NOVICK: And they do feel more comfortable. I am sure it is somewhat disorienting to be speaking about these kinds of things with a camera crew and the lights. We bring a pretty light footprint, but, still, there is a camera person. There is an assistant camera person. There's a sound person. There is a PA. There is a makeup person. Maybe there are four or five people in the room.

We will say, "Ignore all that and just look at me, and we will just have a conversation." So it is very intimate and personal and private.

But there is also deep down in everyone's head an awareness that this conversation is going to be seen by people beyond the room. I don't have words to explain what that means. They are becoming vulnerable not just to us, but to millions of people.

HINDLEY: So many of the recollections were incredibly detailed. They remembered names and units and numbers of hills. I don't want to say you rehearsed them, but did you review with them where they were?

BOTSTEIN: No, never. I think that speaks to how when you are at war your memory is heightened and your world is heightened. The people we interviewed are very special, and they have thought a lot about this time in their lives.

HINDLEY: The film features interviews with Vietnamese participants of the war, many of whom don’t speak English. How did you do the interviews?

NOVICK: We had, first of all, to get to know people there. I made a trip first to Vietnam in March 2012, just to meet people and figure out how we are going to navigate the country and who we are going to talk to and get a sense of how it is going to work. We did a couple interviews then, because there were some very elderly people we were afraid might not be around next time we came back. But, mostly, it was just to get to know people.

When we came back, our soundman, Mark Roy, explained to us a way he had worked in China on another project, which is simultaneous translation with two translators.

I wanted to avoid the experience I had in Baseball: The Tenth Inning update where I interviewed Ichiro Suzuki in Japanese, and we had a translator. He is very dynamic, and he talked and talked and talked, and I am smiling and nodding, but I had no clue as to what he was saying. I lost that moment of connection. I couldn’t ask a follow-up question.

HINDLEY: How did the simultaneous translation work?

BOTSTEIN: Lynn and I both wore earpieces. Then we had a Vietnamese producer, Ho Dang Hoa, who speaks very good English in the room with us. He would reinterpret our question. He was able to translate the question into not only their language, but into the context of the war in a way that would be understandable for them, which is an art in itself.

Then one of our other consulting producers, Ben Wilkinson, was listening in another room down the hall. He would simultaneously translate into our ears what the answers were, so that we could follow along in real time and ask a follow-up question.

They felt like I was hearing them, and I felt like they were hearing me. And it just became a conversation, even though there were two wonderful gentlemen speaking for us.

HINDLEY: It also must have been mentally exhausting, because of that added extra component.

NOVICK: Yes, right. It is mentally exhausting because you are in a different country, and you're just trying to behave properly and understand the customs and be respectful and ask the questions in the right way.

It was also exhilarating, because we met some remarkable people, and they took so many risks in terms of the interviews and revealing themselves and talking about things that are not often said out loud in Vietnam. There were times during the interviews when Ben Wilkinson, who knows a lot about the Vietnam War, would say, "Wow," because somebody said something that he was surprised to hear.

One of the really great gifts of the project was to interview Lo Khac Tam, who in Episode 3 talks about the soldiers being shell-shocked—and shocked—after the battle. Then at the end, he talks about how he couldn't celebrate, because of all the men he had lost, and how he still thinks about all of the missing.

He was very emotional at times. That interview really hit us hard. Here’s a retired North Vietnamese general who has had a wonderful life, and this time in his life is still deeply sad, while it is also a source of tremendous pride.

HINDLEY: The way that they would talk about men that they lost—the words were so guarded.

NOVICK: Right. And every one of them is somebody's son, and they know that. They have to carry that. I often think about the interview with Bao Ninh, the soldier who became a writer after the war. He talks about coming home after the war, and he is the only soldier from his apartment building—out of six who went to war—to come home. He doesn't say much about how that felt to him. He didn't have to. You can just feel the survivor guilt that anyone in that circumstance would feel.

HINDLEY: Many of the interviews touch on painful moments. Losing men. Torture. Suicide. As an interviewer, how do you know how far to push? And what do you do when you get to a door that closes?

NOVICK: Well, the first part is, I don't think of it as pushing.

HINDLEY: That is maybe not the right word.

NOVICK: No, it's interesting. I mean, I've given an enormous amount of thought to this, and I know Sarah and Ken have, too. What we're doing is getting to know people. We show up at their house with a camera crew, and ask them to tell us stories or remember things that are sometimes the most devastating and painful, excruciating events of their entire life. I am not sure I would be able to do that, and I'm not sure I would want to, if the camera were turned on me.

We are acutely aware of what we are asking, and we do it with respect, and hopefully with love and compassion. But we are mindful of what a delicate balance that is.

We just try to be present, which is not so easy in our distracted world, you know? And there is something that happens. We put our cell phones away. We are not reachable when we are on location like that. Our camera crew is totally focused on their jobs. And whoever is sitting in that chair has our complete attention, 110 percent undivided.

What happens is not that you have to push. It is more that you are guiding or just asking another question and helping someone get to the place where it is going to unlock the stories that they might hold back. You let them know it is okay not to talk if they don't want to, and to talk if they want to, and to take their time.

All the people who participated in this film, and I think all the other projects that Ken and I have done, they know what they're getting into. They know why we are there. Once people sat down and started to talk, things unlocked in them, I think, to some degree.

It would be interesting to talk with someone who was interviewed and see if they feel this, because that is the sense that we have, but I have never really asked. I don't even know how to ask someone that question.

HINDLEY: Right. "Did you intend to say that?"

NOVICK: "Did you mean to tell me that?" Right, exactly.

There are many things that we would consider confessions or revelations. I suspect many people have had those thoughts in their heads, but have not said some of those things out loud exactly in the way that they said for our film.

Most of those moments in the film are not the first question that was asked in the interview. It might be an hour and a half in. When they feel comfortable and feel like you want to know what they have to say and you are fully present, things happen, magical things, transcendent things. Sometimes it surprises them as much as it surprises us.

But we rarely have to push. The only thing I would say is that after someone described something awful in a very matter-of-fact way, you might have the follow-up question of, "Well, how did that make you feel? What were you thinking in that moment?" And try to help them get back to what it was like at that time. You’re opening a door, and they can walk in if they want.

I think one of the most powerful moments in the film for me is when Roger Harris, the marine, is talking about an operation along the DMZ. And he said it was a terrible day, and people got shot and killed and run over. Then he said, "I don't want to talk about it," and shakes his head. That moment of him saying "I don't want to talk about it" is more powerful than him telling you more about what happened.

In that moment, I wouldn't have said, "What do you mean? Why don't you want to talk about it?" It's obvious.

What surprised us most, I think, in working on this film was how close to the surface the pain and grief and all the different feelings that the war evokes were. We did not have to dig very deep.

HINDLEY: It is an incredibly emotional experience to watch the movie. I will confess that I cried during Episode 8.

NOVICK: Between My Lai and Kent State and the medic and so many other things, I find Episode 8 completely devastating. It's really tough.

There was a period of time when we were at the height of doing the interviews that I remember saying to Sarah that I think my job is to make grown men cry, because, over and over again, I am talking to people and they are crying, and I am crying, and everyone is crying, because this emotion is being released in a hopefully positive way, but it is profound. It affects you. There is no way it doesn't.

HINDLEY: That is a question that I wanted to ask. How did working on this project affect you?

BOTSTEIN: I think for myself, I would say that it made me want to get the history right and do something special for them, to give back to them for giving us such extraordinary material to work with. It inspired our team and, hopefully the country, to take a moment to think and look at this time a little bit differently.

And that is not directly affecting me personally. I think I am not the same person I was when I started working on the film, and I don't think Ken is, and I don't think Lynn is.

HINDLEY: How do you think you have changed?

BOTSTEIN: I don't know how exactly to really answer that, except I feel like I have learned an enormous amount about—I have thought a lot more about what it means to be a citizen in this country, a patriot, the choices that I might make, the wisdom of the people who made those choices before me, sort of understanding the world I grew up in a different way, wanting to teach my children something different, wanting to find a way for us to listen to each other and grow constructively rather than destructively.

Those sound a little bit like platitudes, but, actually, are somewhat true.

NOVICK: I don't think I am the same person I was when we started this project. I cannot exactly pinpoint what has changed. I am sort of undone at the end of the film when we are summing things up, and Tim O'Brien is reading from his book. The last line he says is “They endured." The idea that people can endure extraordinary—I hate to use that word—but deep, dark loss and tragedy and grief, and still get up in the morning and try to make sense of it and try to look forward and connect with other people—it is really inspiring.

And having gotten to know some really remarkable people and seeing how they live, it is sort of lessons for living. It just got under our skin in ways that we can't even really explain.