It was the winter of 1958—a season of cold and snow—but civic and cultural life in the United States was looking sunny.

Dwight D. Eisenhower was installed in the White House, where he would remain for another three years. The Korean War was a fading memory, and a new agency christened NASA was soon to come into existence. The year’s biggest movie would be Rodgers and Hammerstein’s rousing look back at World War II, South Pacific, and a successful run on the Great White Way was in store for Dore Schary’s commemorative play about FDR, Sunrise at Campobello.

On January 17, in the New York City Center, a new ballet was unveiled that reflected the country’s benevolent self-confidence.

Its music did not come courtesy of Pyotr Tchaikovsky or Sergei Prokofiev or even Igor Stravinsky. No, this ballet was meant for the resolute rhythms of John Philip Sousa, the Washington, D.C.-born march-making composer whose tunes came to embody the institutions, like the U.S. Marine Corps, they celebrated. The ballet’s finale featured a veritable division of dancers—men donning cadet-style uniforms and women wearing tutus of red and blue—who strutted and spun while a prodigiously sized American flag, running the width of the stage, emerged behind them. The title: Stars and Stripes, of course.

Amateurs in the audience would have been forgiven for supposing that Gen. Douglas MacArthur had temporarily commandeered control of the New York City Ballet, the company that was debuting the dance that day in 1958. But balletomanes would have known that its creator was an expat from St. Petersburg, Russia, who still spoke with an accent that would never be mistaken for Boston Brahmin or Southern drawl.

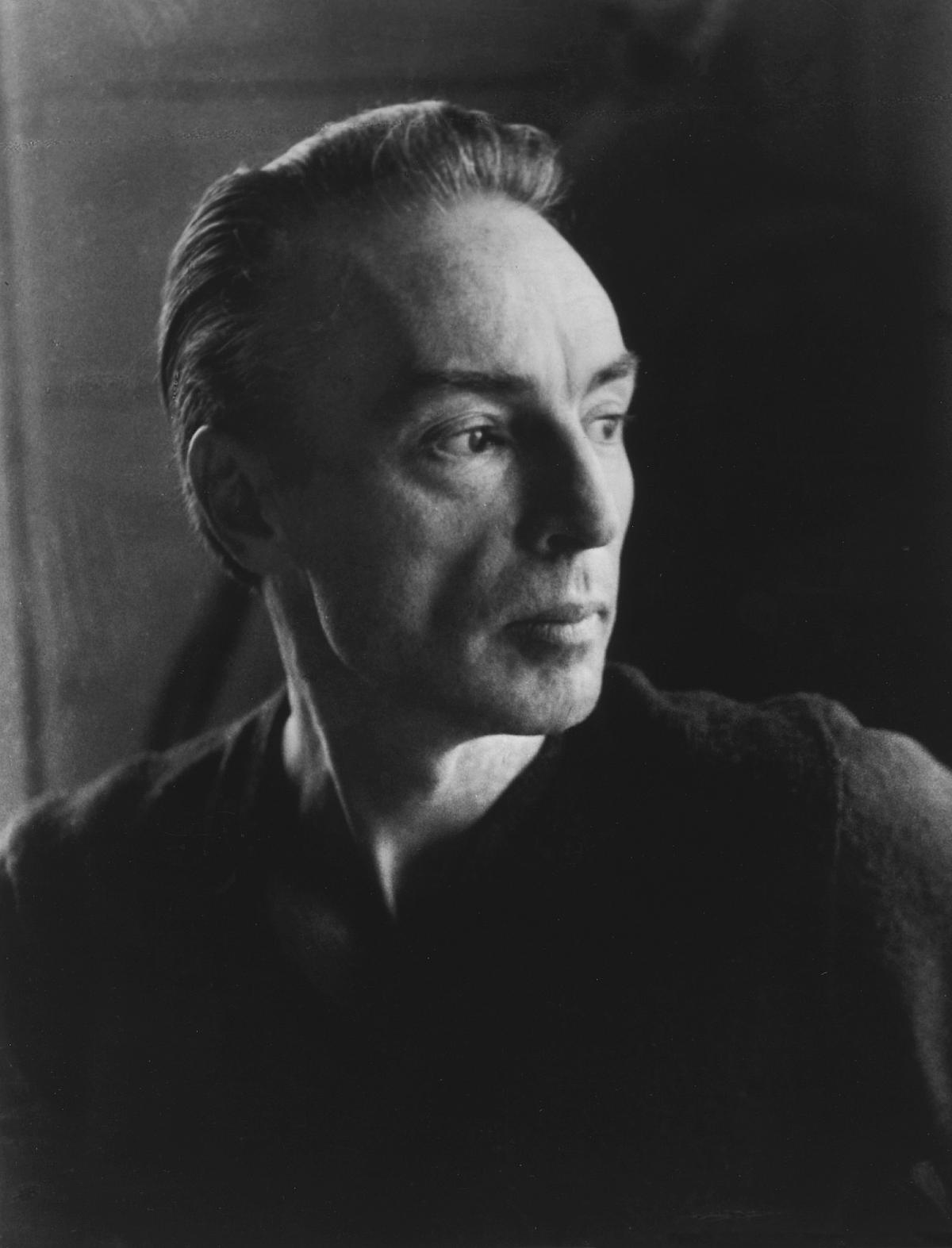

His name was George Balanchine (1904–1983; pronounced “Balan-sheen”), and then—as ever—he frustrated expectations.

An artist’s home turf is frequently his biggest inspiration: Philip Roth situated much of his best fiction in Newark, New Jersey, while Andrew Wyeth often looked no further than Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, for potential paintings. And so attached was James Thurber to Columbus, Ohio, that he said “the clocks that strike in my dreams” were those of his hometown.

Not so with Balanchine. Of course, it is self-evident that his salad days in Russia—and, later, on the continent—were key to his later triumphs. As his dancing talent was developed at the Imperial Ballet School, his flair for music was honed at the Petrograd Conservatory of Music, where his instrument was the piano.

“Mr. B. frequently would say he had wonderful teachers when he was growing up in St. Petersburg,” says dancer Suzanne Farrell, who followed her famous collaboration with Balanchine at the New York City Ballet by forming her own company, the Suzanne Farrell Ballet at the Kennedy Center. But, she added of Balanchine’s roots in Russia, “he took much of it with him to America and re-weaved it onto American dancers, developing a completely different style.”

An appointment to Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris was also career-changing.

“Diaghilev had named him ballet master at age 21,” says Violette Verdy, a French dancer recruited by Balanchine to become a member of the New York City Ballet in 1958, “because he could see the reflection, the depth, the silence, the thinking, and the creativity.” Indeed, the partnership resulted in Apollo (1928)—a Balanchine masterpiece—which marshaled modern music by Stravinsky to spin the saga of the Greek god Apollo contending with female muses.

But once the United States became Balanchine’s base of operations in 1933, he found creative nourishment not in his old backyard, but in his new stomping grounds.

“He loved the American spirit,” says dancer Patricia McBride, who was 16 when she joined the New York City Ballet, and remained with the company for six years after his death.

In the introduction to their book Balanchine’s Ballerinas: Conversations with the Muses, Robert Tracy and Sharon DeLano write: “Like many emigres from Soviet Russia, Balanchine was politically conservative and enamored of the American scene. He wore cowboy shirts with pearl snaps, Western-cut suits, string ties, and turquoise bracelets.” They went on to make note of a performance on Independence Day 1982 when Balanchine announced “that he had just received a new composition from Stravinsky, and the orchestra played ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’”

“I think he liked America for the entertainment of it,” says Wendy Whelan, a recently retired dancer with the New York City Ballet who never worked with Balanchine but danced in many of his ballets. “I think he liked American movies and American shows and the American energy.”

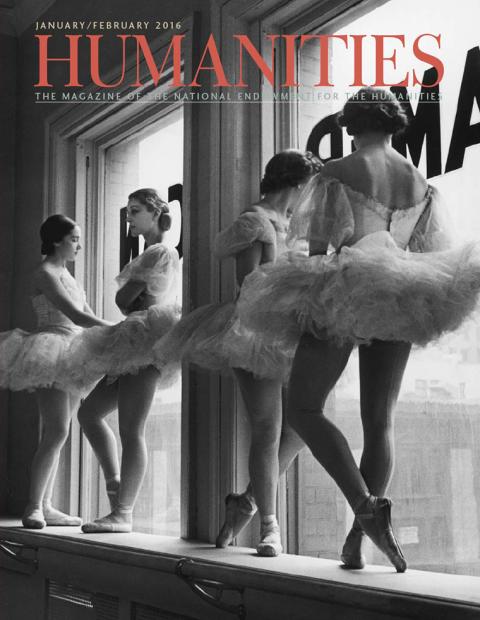

So, it was in the U.S. of A., in 1934, that Balanchine shepherded into being the School of American Ballet, the organization that would, in 1948, beget the New York City Ballet. Both came about due to cofounder Lincoln Kirstein, a son of Rochester, New York, whose sponsoring of the arts had already encompassed the formation of Hound & Horn, a literary magazine par excellence. Kirstein, Verdy says “had decided that this wonderful big country of the United States should have ballet,” adding, “but he wanted the real thing. . . . So he said, ‘We’re going to have to do ballet.’ The one person to go to was Balanchine.”

It was rough in the early going, though. In his biography of Balanchine, Bernard Taper describes the earliest photograph in existence of the choreographer at work stateside, as he toils on his magisterial ballet Serenade (1934) with students of the nascent School of American Ballet. “Looking at the snapshot, one can readily see why it was felt that ballet dancing was no activity for Americans,” Taper writes. “It just does not seem possible that anything remotely like a ballet troupe could ever emerge from this hodgepodge of chubby, self-conscious young women in homely, one-piece bathing suits.”

Nonetheless—as unsatisfactory as that class may have been—Balanchine seems to have recognized the resources in the country he had relocated to. “He took the Americans for what they were: tall, beautiful, long legs,” Verdy says. “He always told me . . . ‘You know, my best dancers come from the states that have a lot of sun, like Texas.’ Because it was sports and they have the belief of sports, which means they can have a body for ballet, too.”

For Balanchine, “like Texas” seems to have meant virtually anywhere in the continental United States: Over the years, dancers with the New York City Ballet have been found in New York and nearby states, of course, but also in Staunton, Virginia (Diana Adams), Cincinnati, Ohio (Suzanne Farrell), and even Southern California (Allegra Kent and Darci Kistler). Maria Tallchief (who eventually became the third of his four wives) hailed from Fairfax, Oklahoma, and her father was an Osage Indian. Writes Taper: “It made him feel that in marrying her he was becoming really American—John Smith marrying Pocahontas.”

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. The School of American Ballet would endure, but, as the 1930s entered the ’40s, the failed “ancestors” of the New York City Ballet were legion, including such outfits as the American Ballet and the Ballet Caravan. Thus, Balanchine—needing employment—attached himself to lollapaloozas that ranged far afield of ballet in its most traditional guises. Ziegfeld Follies of 1936, Babes in Arms, and Cabin in the Sky were among his credits on Broadway, while in Hollywood he was responsible for choreography in The Goldwyn Follies and On Your Toes. The latter production—a tawdry tale that was also a stage show by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz “Larry” Hart—included a brooding number entitled Slaughter on Tenth Avenue, which matched a sultry score with the spastic, almost violent movements of high-heels-wearing dancer Vera Zorina (who preceded Tallchief as Balanchine’s second wife).

In a New York Times article by the critic Jennifer Dunning, an assistant of Balanchine named Barbara Horgan discussed the influence of Hart on Balanchine—a classic, touching example of an immigrant’s assimilation. “Larry Hart taught him English,” Horgan said. “He didn’t know any English when he came to America. Someone taught him to order ‘ham and eggs and bacon,’ but he didn’t like bacon so he changed it to ‘ham and eggs and no bacon.’”

“This man had to wait so much to be recognized,” Verdy says, adding, “He never thought that any job was too small for him. Hence, he did all of those films to survive. He did little things, little ballets for big, very wealthy people who had a little ballet in their soiree. He never refused any work that could come.”

But Balanchine took his contributions to stage and screen seriously.

“We owe (him) the word ‘choreographer,’ which of course exists,” Verdy says, referring to Balanchine’s insistence that he be credited as such on a particular production. “I mean, he didn’t invent it, but . . . he was the one, when he was doing one of the Broadway shows that he did in his early years . . . who demanded from the producer that they would stop to say, ‘Routine by such-and-such.’”

There were other, more momentous innovations.

Balanchine untethered ballet from the baggage that had been weighing down the form since time immemorial. “I think, for the most part, before Balanchine, it was very much spectacle and something outside of the dancer,” Whelan says. “It was the costumes. It was the set. It was the story. It was the drama. It was the pantomime.”

In such ballets as The Four Temperaments (1946) and Agon (1957), Balanchine abolished scenery and turned rehearsal clothes into costumes. (“On the funny side,” Verdy recalls, “he said to me, ‘We just don’t have money to have costume!’”) But even ballets with less severe aesthetics—Western Symphony, with its dancers gussied up like cowboys and showgirls—usually skipped the over-the-top characterizations and fairy-tale plots of classic story ballets, like Swan Lake.

Indeed, it is instructive to contrast Western Symphony with a superficially similar work—Michael Kidd’s choreography in the musical film Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. The two works—remarkably, both debuted in 1954—seem to have so much in common: the application of ballet technique to tableaus suggesting the western half of the United States. But while Kidd’s choreography decisively advances the film’s storyline—as in “Goin’ Courtin’,” in which Jane Powell seeks to bring manners to the bush-country brothers—Balanchine’s has no aim but to make movement befitting music (in this case, Hershy Kay’s settings of such songs as “Red River Valley”). Western Symphony and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers are akin to poetry and prose: One form is about the kindling of a mood while the other is about the propulsion of a plot.

Not that Balanchine’s ballets don’t put forth definite ideas and attitudes. To the contrary, in Western Symphony there is no mistaking the rangy self-confidence of Herbert Bliss or the wily impudence of Diana Adams, both members of the original cast. (“When he did the last movement for Diana Adams, with her long legs and also her cool quality—she wasn’t involved,” Verdy says. “Her body was doing it—not Diana.”) To put it another way, the parts danced by Bliss and Adams call for the projection of qualities consistent with a cowboy and a showgirl, but neither dancer is asked to inhabit an actual character. “He made things without story, generally, and he never wanted dancers to act,” Whelan says. “He wanted to see the dancer feeling the music or just dancing the dance with the music, and how that could be as emotional as any kind of put-on story.”

Music, for Balanchine, was the be all, end all.

“He always said, ‘If you don’t watch the ballet, just close your eyes, and listen to the music, and it will be great music,’” McBride remembers. Indeed, a multitude of musical masterpieces can be heard along with his ballets: Tchaikovsky’s Orchestral Suite No. 3 in Theme and Variations (1947); four selections of Charles Ives in Ivesiana (1954); Louis Gottschalk’s Grande Tarantelle in Tarantella (1964); and a bevy of George Gershwin songs in Who Cares? (1970).

But those who keep their eyes and ears equally alert will discover a choreographer singularly attuned to finding correlatives to music. “Peter Boal, one of my colleagues, was working on Mozartiana with Suzanne Farrell, and she was helping him learn the part,” Whelan says. “And they were watching the pianist’s hand crisscross . . . and, interestingly, when you looked at the choreography in that moment, the bodies were crossing over as well.”

Few Balanchine ballets offer a better example of how bodies can adapt themselves to changing tones and tempos of music than Union Jack (1976), in which the choreographer sailed across the Atlantic—metaphorically speaking—to embrace Great Britain. In one ebullient passage, three spirited sailors—two men dressed in navy, one woman in white—kick, sway, and salute, but when Hershy Kay’s arrangement of “Rule, Britannia!” is cued up at the end, the corps momentarily pauses, makes itself ramrod straight, and then starts to march in sharply defined patterns.

On the basis of Western Symphony and Stars and Stripes, Balanchine is a celebrant of the United States on par with Aaron Copland (for Appalachian Spring and others) or John Ford (for Young Mr. Lincoln and others)—and, on the basis of Union Jack, he was a believer in Winston Churchill’s notion of a “special relationship,” too. But even his many ballets that do not partake in national iconography—like Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux (1960) or Tarantella—exploit the zest and brio of the nation. Whelan says that Balanchine sought speed—that is, more moves in less time. “That was typically what he thought of as American in that sort of progressive boom of technology and post-World War, making things happen, and not wasting time and being in a New York state of mind,” she says, adding, “A lot of what we study in class is the speed, the timing, the directness of line.”

One day, Balanchine explained to Verdy one of the reasons that he was a fan of American dancers—the Russian choreographer confiding to the French ballerina. “He said, ‘You know, Americans don’t have style,’” Verdy recalls. “So, I jumped at him: ‘Mr. B.’! He said, ‘No, I mean they are not preconceiving style. They don’t have to do style. They do exactly what you ask them to do. They have a huge technique, and they have speed. They don’t even know that you can’t dance that fast. They do it if I ask.’”

Yet, while crafting his ballets, Balanchine also made himself one with his dancers, according to McBride: “He could show so beautifully. Everything was there, and you’d just do it behind him. And he worked so fast that you had to keep up with him, because his mind worked so fast.” She says that it was the greatest of gifts to have a ballet created especially for her, and it was a joy to learn it from him in the studio: “There was an intimacy that you had working with him when he partnered you. You fell in love with him and his genius.”

Many ballerinas beguiled Balanchine, too; and Farrell, McBride, and Verdy were but a few of his muses. In 1965, in an article in Life magazine, Balanchine wrote: “The ballet is a purely female thing; it is a woman, a garden of beautiful flowers, and man is the gardener.” This attitude, so suggestive of the Old World, was in fact in tune with American culture as Balanchine found it: the idea of a woman being inherently worthier than a man is as old as Henry James’s Daisy Miller (1879).

In Evan S. Connell’s Mr. Bridge (1969), the following thoughts are amusingly placed in the head of the Midwestern businessman hero, upon going to a ballet for the first time: “For young girls to spend their lives dancing seemed perfectly natural, they were charming. . . . But the male dancers puzzled him. No doubt they were necessary for the show, and he could not think of any specific reason the young men should not be dancing; all the same he did not quite like it.” The question is: Would George Balanchine disagree?

To be sure, Balanchine hardly shortchanged male dancers. The likes of Jacques d’Amboise, Edward Villella, and Mikhail Baryshnikov were seen in such forceful, challenging dances as Apollo or Prodigal Son (1929). And, in a conversation with former New York City Ballet dancer Damian Woetzel in 2011, the company’s present Ballet Master in Chief, Peter Martins, said: “Most of you who are familiar with ballet probably have heard the famous saying that Balanchine coined, ‘ballet is woman.’ . . . It always bothered me—you know, this is the greatest choreographer who has ever choreographed so many great works for men, and he was never really acknowledged for that.”

Even so, there is no denying that femininity reigns in Balanchine’s ballets. In a 1982 interview in Balanchine’s Ballerinas, Farrell said that “so many dancers work on building up strength to the point where they become unfeminine. Tough. Yet ultimately our job is to entertain. To be beautiful to look at.” And Balanchine’s ballerinas always were. Says McBride, succinctly: “He knew what a woman could do in pointe shoes, which was very rare.”

About three months after Balanchine’s death, Jennifer Dunning reported in the New York Times of the choreographer’s decades-in-the-making plans for a Morton Gould-scored work, “based on American themes and revolving around a hero based on both Johnny Appleseed . . . and a Tom Sawyerish John James Audubon, the naturalist whose book of drawings, The Birds of America, gave the ballet its name.”

Gould said that the ballet was to be “a glorification of this country and the joy of living, moving, the air, space and the body.” This, of course, calls to mind so many previous Balanchine ballets extolling America and its riches. But while The Birds of America is lost to the sands of time, it turns out its creator was, in his own fashion, a choreographic cousin to Johnny Appleseed—sprinkling dances from sea to shining sea.

“His impact has touched . . . every major city of the world,” says McBride, who—as associate artistic director of the Charlotte Ballet in North Carolina—regularly finds herself staging Balanchine’s ballets, a task she undertakes with a fresh perspective.

“I always knew my roles well, and I could stage my roles,” McBride says. “But, years ago, when I stopped dancing in 1989, I started staging his works, and it was mindboggling to see what he did for the corps that was behind me.”According to Whelan, Balanchine’s ballets do well on the road.

“Even a small company in Mississippi or Alabama or . . . Oklahoma could do a Balanchine work, and just practicing the choreography will make you a better dancer,” Whelan says. “Just learning the steps that he created, in the way he created them, with the musicality and pushing yourself . . . you just automatically improve and become a better, stronger, more interesting dancer.”

Whelan adds: “One of my favorite things is energy produces energy, and Balanchine’s work is so much about energy that it can’t help but bubble up like joy and excitement and just positivity.”