For many years after it was donated to Yale University in 1962, a detailed world map completed in 1491 by Henricus Martellus and in all likelihood consulted by Christopher Columbus hung unobtrusively on a wall outside of the reading room of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Potentially, the map had much to say about the intellectual rapport between cartographers and navigators in the fifteenth century, but many legends were unreadable. And yet where the text was legible, it revealed ways that Europeans of the day imagined the rest of the world. These impressions were sometimes based on the writings of Marco Polo, and others came from dignitaries visiting Europe from Africa. Even so, a great many of the legends allude to fantastically shaped critters and beings.

Martellus, a German cartographer working in Florence, used Ptolemy’s geography and projections from the second century CE and modified them to reveal a greater swath of the earth’s surface than almost any previous mapmaker had shown on a flat map. How and when Columbus consulted the Martellus map is not known, but historian Chet Van Duzer is nearly certain that he did see it or a very similar map.

Scholars such as Van Duzer have had hopes of bringing obscured texts on the map to light, and figuring out how people of the time conceived of the world. With funding from NEH, he led a team of scholars and imaging experts from the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, Megavision, the Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science at the Rochester Institute of Technology, and the Lazarus Project at the University of Mississippi to unlock the map’s secrets. Now, with the help of imagery work, it is quite easy to look at the Martellus map and find the same western route to India that enticed Columbus.

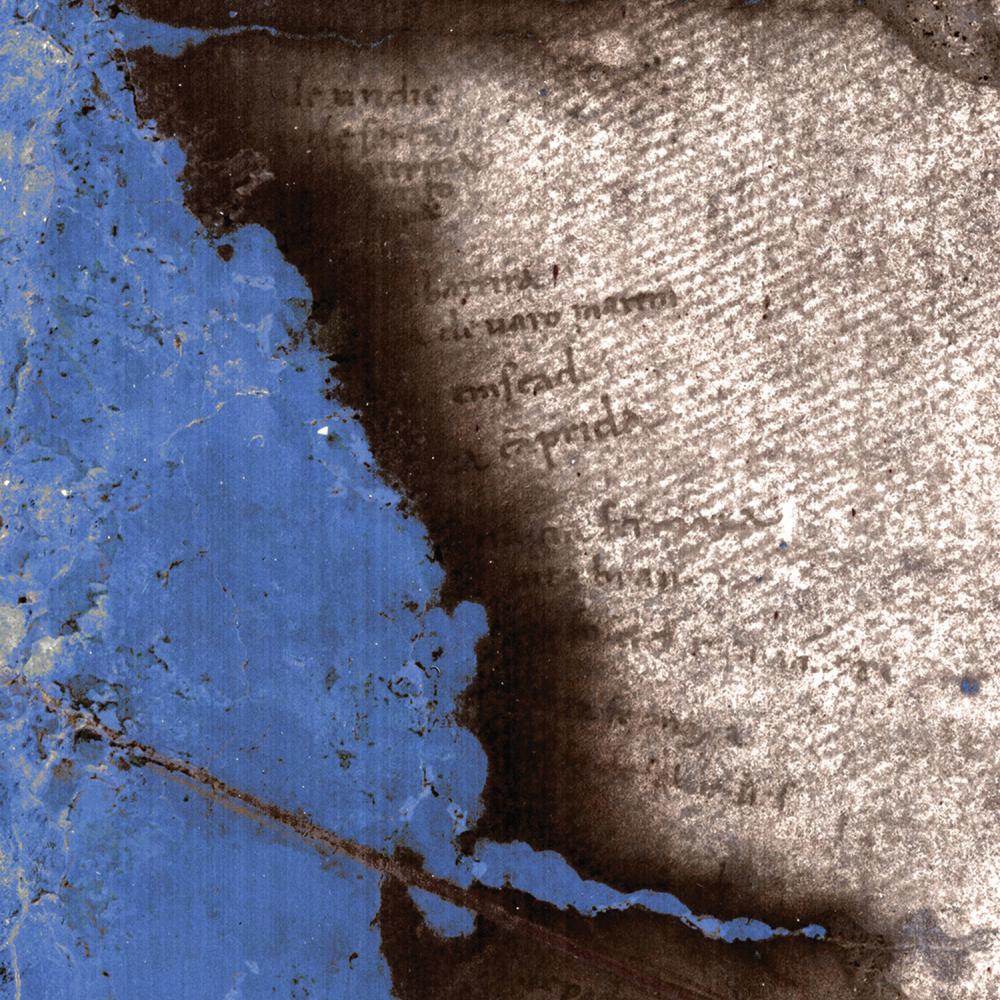

“Shortly after the Martellus map surfaced,” Van Duzer wrote by e-mail, “some photos were taken of it in ultraviolet light, and one of these in particular showed that northeastern Asia, where one hardly sees any text at all with the naked eye, is in fact dense with text.” It took decades for multispectral imaging technology to develop to the point where scholars would be able to read the legends. But the Martellus world map, which is six and a half feet wide and four feet tall, presented yet one more challenge. “Transporting it to a laboratory for the multispectral imaging,” Van Duzer said, “would have been detrimental from a conservation point of view, and difficult in terms of insurance.”

Fortunately, portable multispectral imaging tools have recently become more common, and Gregory Heyworth of the Lazarus Project has developed some that can be used with fragile artifacts.

Heyworth and the Lazarus Project team traveled to Yale to photograph the Martellus map. Years ago he began carrying his multispectral imaging tools in a golf bag in order to get around some airline restrictions regarding baggage. Not a golfer, he slips a green plastic putter and golf ball into the bag as a ruse, which smooths the way with airport officials but can also be the source of some embarrassment. While at Yale, a staffer there extracted the green putter with a quizzical look while Heyworth, chagrined, had to quickly explain.

Another participant in the project, Roger Easton of the Rochester Institute of Technology, talks about other, more technical, problems, pointing out that “since the map really is a painting rather than a manuscript, the contrast between the writing and background varies all over the place. . . . We often have to come up with some new methods to recover local sections of text, and these methods generally are not helpful for the next block of text nearby.”

While reflecting on his role in the work on the Martellus world map, Easton, an imaging scientist, takes the long view of the connection between the humanities and technology: “I feel as though I am an ally of the scribe who originally wrote the words. It is not a stretch to say that the scribe was an imaging scientist of his time. He was trying to preserve words by using the most advanced archival technology. These words were then ‘lost’ through no fault of his. We are trying to recover those words using modern descendants of the technology he used to write the original words.”

The recent types of multispectral technology developed by Megavision in California and at the Lazarus Project and used to more fully view the Martellus map have also been used in such groundbreaking projects in the digital humanities as the Archimedes palimpsest project and on the David Livingstone diaries.