Many discussions of the humanities turn on the problem of definition: Why can’t we reliably sum up the humanities in, let’s say, ten words?

I honestly don’t know. But I do happen to know that coming up with definitions is harder than it seems. And during a recent discussion, when the old definition card was played, I started to feel like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart when he balked at defining obscenity, saying famously, “I know it when I see it.”

But do I? Our office had a call the other day from someone asking us to recommend an image to use on an invitation for a big humanities event, an image, the caller specified, that clearly says, “humanities.”

And I thought, just one image?

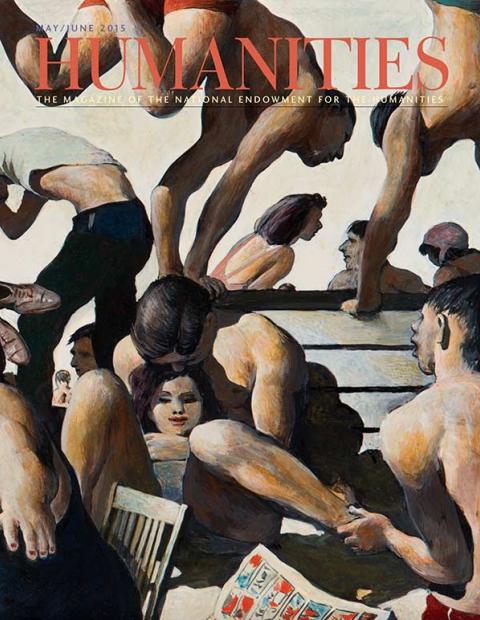

Forced to choose, I might go for an ancient statue or Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian man. What I probably would not choose—and here I would be mistaken—is an image of Coney Island, which, for me, always brings to mind a certain kind of fleshiness that is, among other things, too great for the bathing suits trying to contain it.

Coney Island is what the Puritans were warning us about. But it also happens to be where Isaac Bashevis Singer once described himself as verging on the great truth of being and time. In A Coney Island of the Mind, the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti waits for “a rebirth of wonder.” And Coney Island is where I used to be taken on field trips with other kids from my summer camp, a buck or two in my pocket from Mom and feeling kind of scared.

Coney Island is very human, very New York, and, as Tom Christopher shows in his article about an NEH-supported exhibit at the Wadsworth Atheneum in nearby Connecticut, very American.

Speaking of the very human and New York, we also have a rather funny piece on the history of journalism in which Andie Tucher considers how different Gotham newspapers covered the same human interest story in 1904.

Not much later, Americans were receiving news through that newfangled invention, the radio. Katy June-Friesen describes one of the boldest experiments in early radio: the so-called super station WLW, whose signal was strong enough to cross the country.

The early twentieth century was famous for its bold experimenters, not least in literature. Danny Heitman revisits the prose and woes of the great modernist Virginia Woolf, who is sometimes unfairly remembered as just a women’s writer.

Madam Sacho is barely remembered at all. Sarah M. S. Pearsall attempts to pull this curious figure from the mists of history and reconsider her in the light of the American Revolution and the future of U.S. Indian policy.

And remembering, I happen to think, is more important than defining.