I remember a college professor saying that in our papers for his class we should sound not like lawyers, but judges: reserved and impartial. It is the objective voice we know from instruction manuals, reference works, and even some magazines. Well, this issue of Humanities is about the opposite of all that.

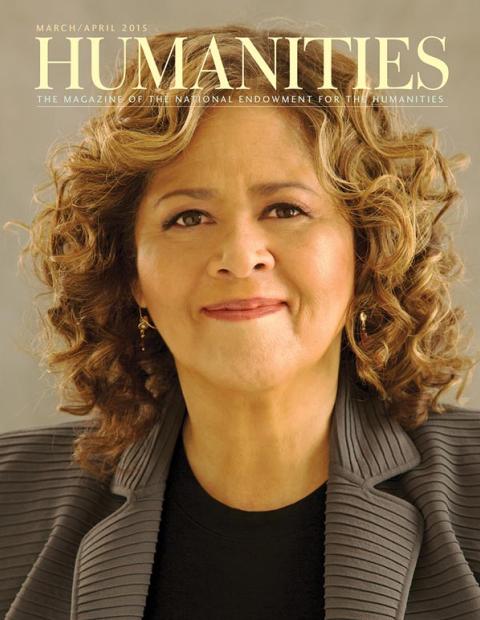

The 2015 Jefferson Lecturer Anna Deavere Smith discovered her voice as a performer when she noticed the power of other people’s voices as they told their own stories, from their point of view, in their own words. For the first production in her long-running and much-celebrated series, “On the Road: A Search for American Character,” Smith approached complete strangers with a proposition: In exchange for their story, they would be invited to see themselves portrayed by an actor on stage.

One high point was a stage piece in which Smith appeared as twenty-nine separate characters all reacting to the same catastrophic events in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, in 1991. I will say, as someone who grew up in the Big Apple, that this is my favorite of her works. The personae comprised a wild, only-in-New-York assortment of the pious and the blasphemous, the cynical and the foolish, the outrageous and the outraged.

Her work makes one think of Tom Wolfe’s phrase for the American story, “the billion-footed beast,” and yet her popularity is a credit to the fact that, as she says, “the canon has changed in every way, dramatically not just with regard to race, gender, and sexuality. The official American voice has changed.”

The playwright August Wilson was certainly a part of that change. A great student of African-American vernacular, he spent untold hours in diners and bars in Pittsburgh taking notes on the things black people said. Michael Eric Dyson pays tribute to Wilson’s work, showing how the playwright used the blues to create a new kind of poetry for the stage.

Everyone has a story to tell, especially veterans. Iraq war veteran Jacob Siegel writes about the work of Aquila Theatre in exposing veterans to classical Greek plays and another program that gives dramatic form to veterans’ modern-day war stories called YouStories.

Montaigne’s essays might be called I-stories. They are about Montaigne—his life, his thoughts, his reading. As Danny Heitman shows, the democratic spirit we see in Anna Deavere Smith, August Wilson, and Aquila Theatre finds a precedent in Montaigne’s realization that the passing thoughts of a retired gentleman might be reason enough to uncap one’s pen and put it to paper.

And yet there are events that erase our differences. Lincoln’s assassination, one hundred fifty years ago, was such an event. In her examination of this national tragedy, NEH research fellow Martha Hodes shows that the same two words were suddenly on the lips of many Americans: very and sad.