If the great values of the liberal arts are curiosity and tolerance, then Walter Isaacson is a great humanist. He shares this gift as a wonderful storyteller.

One of his favorite stories is about his daughter, Betsy, with whom he has a teasing, close, and sweetly affectionate relationship. A few years ago, when Betsy was a precocious teenager, already aware that all biography is, as Emerson said, autobiography, she had some fun with her father. She ticked through his books. Ben Franklin, she said, is “an idealized version” of Walter himself. And Einstein, she said, was Walter’s father, Irwin. Walter had to agree that his father was, like Einstein, “a kindly, Jewish, distracted humanist engineer with a reverence for science.” Kissinger? “You were writing about your dark side,” said Betsy. And as for Steve Jobs … ”I worry,” Betsy said, “that you were writing about me, a bratty kid who likes art and technology.” “Hmmm,” replied Walter. “Maybe so.”

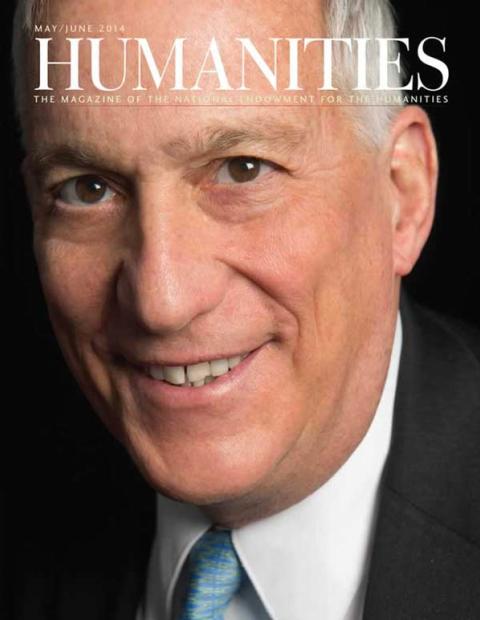

I can see Walter’s smile widening as he tells that story, his eyes lighting up with all that is delightful about the quirks of the human condition and the abiding wonder of family love.

I met Walter when he came to work at Time magazine, where I was also a junior writer, in the winter of 1978. I knew immediately that I, along with my colleagues, would all be working for him before too long. He was magnetic, multitalented, and he already seemed to know everyone who mattered. Even then, Walter attracted crowds of all kinds—friends, mentors, protégés, intellectuals, celebrities. Our mutual friend Steve Weisman recalls visiting Walter in the Hamptons and attending eight brunches, lunches, dinners, and cocktail parties in one weekend. I once accompanied Walter on a men’s cruise to Nantucket, where he disappeared into a teenybopper bar and emerged with NBC anchorman John Chancellor. These days, every summer at the Aspen Institute, Walter brings together an astonishing lineup of doers and thinkers—industrialists, artists, tycoons, techies, ex-presidents, statesmen, actors, gurus, scholars, and social and scientific activists of one kind or another. Aspen “is his own university,” says his friend Kurt Andersen, the novelist and public radio host.

Walter celebrates his friends. He had been a year behind me in college, and I would later hear him tell people, in his generous and expansive way, that we had been friends there. I wish we had been, but I’m not sure we ever met then. “He was the mayor of literary Harvard,” recalls Andersen, who was two years behind Walter on the Lampoon. “You could see where he was headed.”

At Time back in 1978, I knew I wanted to be his friend right away. He was warm and funny and endlessly curious and interesting. You wanted to talk to him all night, and, during Time’s endless closing nights, I sometimes did.

During one of those conversations, he told me that, while home for the holidays during his last year as a Rhodes Scholar, he had been summoned to an airport motel and approached by a high official of the Central Intelligence Agency, who tried to recruit him. The agency, to its credit, was looking for the next generation’s best and brightest. It is interesting to speculate about Walter’s life and career if he had become a spy. More than anyone I have ever met, he can get anyone to tell him anything. But Walter was too openhearted for a life in secrets, and he had already been won by journalism.

After Oxford, he went home to work for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, covering local politics. Within a year or two he knew more about the underside of Louisiana politics than the character Jack Burden in All the King’s Men. Inevitably, his talent was discovered, and he began his fast climb at Time.

Walter did not disguise his ambition in those days, though never at the expense of someone else. “He wanted to succeed,” recalls Andersen, “but he wanted his friends to succeed, too.” In 1988, when he was well on his way to the top at Time, he invited his fellow Time Inc-ers in town for the Republican National Convention, to visit his childhood home in New Orleans. The managing editor, Henry Muller, poked his head into Walter’s old bedroom and came down and told his colleagues, “I couldn’t help imagining Walter looking out the window and seeing New York.”

Walter always came back to his hometown. Later, when he was famous, he and Wynton Marsalis, another son of New Orleans, talked about writing a love ode to the Big Easy. After the city was nearly destroyed by Hurricane Katrina, Walter spent many months traveling back to serve as vice chairman of the Louisiana Recovery Authority. (Walter’s streak of public service is high and wide. He has also served as chairman of Teach for America and as a trustee at Tulane—and as an overseer at Harvard and as Chairman of the Broadcasting Board of Governors, a presidential appointment.)

Walter has always been tolerant and inclusive. He may have gotten that from being a well-loved child (he also has one of the great marriages, to his wife of thirty years, Cathy), or just by growing up in the gumbo of New Orleans. His father is Jewish, but on his mother’s side are some Christians, and one week on a trip upriver into the Bible Belt, when Walter was about twelve years old, he was baptized by some evangelical aunts. Walter was not exactly greeted as “saved” when he got home, but the experience may have added to his ecumenical view of the world. As a six-year-old, Walter remembers, he was unable to ride a merry-go-round that was marked with a Whites Only sign because he was accompanied by his black housekeeper and her son. “We learned to wonder why,” he later said.

Journalists are seen, and sometimes deserve to be seen, as cold-blooded exploiters. “We don’t have good reputations as humanists,” says Strobe Talbott, Walter’s longtime friend from Time who is now president of the Brookings Institution. “Feral beasts. Cynical, just out for the sensational. Walter is a rebuttal to all those clichés,” says Talbott. “He is genuinely curious about what makes people tick. He is in equal measure hardheaded and bighearted.”

As editor at Time, Walter adopted the idea of “common ground” as a mission of the magazine. “I thought it was advertising claptrap,” said Jim Kelly, another longtime friend who succeeded Walter as editor. “But he believed it so fervently that he made all of us into believers.” Walter has worked for years on improving Israeli-Palestinian relations—in 2007, he was appointed by President George Bush to be chairman of the U.S.-Palestinian Partnership, seeking to create economic and educational opportunities. “It’s painful to him when people aren’t talking,” says his friend Steve Weisman, former New York Timesdiplomatic correspondent. “I sometimes wonder if he isn’t a little naïve, but he is patient and idealistic.” Walter’s eagerness to connect people makes him one of the great mentors; he has wisely advised (and helped place) a long list of young people.

When he needs to be, Walter can be shrewd about diplomacy and power politics. His decision to write a biography of Henry Kissinger tested his mettle, as well as his generous nature, in all sorts of ways. One day while he was writing the book, he received a phone call from Kissinger’s office. Would Mr. Isaacson please come to the Kissingers for Thanksgiving dinner? Walter was “tortured,” recalls Weisman, worried that if he accepted such an intimate invitation he might be sacrificing his objectivity and independence. As he was wrestling with this dilemma, he got another, slightly embarrassed call from Kissinger’s assistant. Kissinger had, um, said, “Invite Isaac Stern,” not Isaacson, explained the assistant. I can see Walter’s twinkle as he tells that story.

Though Walter did a masterful job of guiding CNN through 9/11 and its aftermath, he is, at heart, a print man. Walter likes stage plays—especially Shakespeare—but he is bored and restless at movies, and usually refuses to go or he leaves early. He is not prurient, and immersive violence makes him uneasy. He doesn’t watch much TV, and he did not relish fighting the cable news rating wars. He was much more content writing about Benjamin Franklin, whose biography Walter wrote at night while he was running CNN (Walter’s capacity for work and his ability to shift focus without missing a beat are beyond description).

His daughter, Betsy, was right about biography as autobiography: Walter identified with Ben Franklin, with his love of invention and ingenuity, his practical intelligence and skills as a great communicator. Walter is curious about everything—the Fourth Dimension, the discovery of electricity, the rise of Silicon Valley, and “how to deep-fry a turkey at Thanksgiving,” says Kelly. It’s not hard to imagine Walter fiddling around with kites in a storm.

“He admires people who took a chance,” says Alice Mayhew, who has been Walter’s editor at Simon and Schuster for over thirty years. Walter took a chance by writing his book about Albert Einstein. To reach a popular audience, he had to be able to explain Einstein’s theories of relativity. The book, a huge best seller, includes mathematical equations. Fortunately, says Mayhew, Walter is a little bit like Einstein, in that he can visualize scientific formulas. “Make us see,” said Charles Dickens, and Walter, remarkably, was able to make us see what Einstein saw.

Like Einstein, Walter stands at the intersection of the humanities and science. (Or, as his longtime friend and literary agent Amanda Urban puts it, “He’s an empathetic geek.”) He is fascinated by the power of imagination and interested, always, in the human dimension. Perhaps that is why Steve Jobs, a difficult, demanding loner, ill much of the time and the most private of men, was able to trust Walter and to tell him so much.

Walter is not religious. And yet, in Einstein, he showed “an uncanny understanding of religion and Judaism,” says Weisman. “He understood that Einstein was an atheist who believed in God, that the underpinning of what Einstein was pursuing was a search for God.”

In the late 1990s, James Watson, the Nobel Prize-winning scientist, came to Time to meet with the editors. Asked about “intelligent design,” Watson was “contemptuous,” recalled Jim Kelly, who was at the lunch. Kelly, who is Catholic, told me:

Watson, in his blunt way, said anyone who believes in God was a fool and all religions are poppycock. We were all too polite (or intimidated by the codiscoverer of DNA) to counter his dismissive attitude, and afterward I went into Walter’s office to tell him how great the lunch was but that something Watson said left me depressed. Before I could say anything, Walter pointed to Watson’s dismissal of believers and said there is another way to answer the question: the way Einstein answered it, by saying that any serious scientist knows that some kind of spirit is behind the laws of the universe. Not a human-like God that directs the fate of individuals, but one that is revealed through the harmony of the universe. And Einstein, Walter said, never derided believers. That was fantastically comforting to me.

Kelly told me that Walter had spoken “without rancor.” He wasn’t deriding Watson. It was a busy day, and Walter had a magazine to put out. But he instinctively knew what was bothering his friend, and in a profound way was able to help him. There are lots of Walter stories, but I think that is the one I like best.