In the 1970s, college students in archaeology such as myself learned that the first human beings to arrive in North America had come over a land bridge from Asia and Siberia approximately 13,000 to 13,500 years ago. These people, the first North Americans, were known collectively as Clovis people. Their journey was made possible, according to archaeologists far and wide, by a corridor that had opened up between giant ice sheets covering what is now Alaska and Alberta. Thus did the Clovis people move down through the North American continent, carrying their distinctive tools to various sites in the Plains States and the Southwest and then moving eastward. And all of this they did very quickly.

Significant evidence of Clovis culture had been discovered in New Mexico. In 1908, a rancher riding along an arroyo on his property near Folsom noticed what looked like large bones embedded in the embankment. They turned out to be from gigantic Ice Age bison and other late Pleistocene megafauna, such as mammoths, and they had cut marks that had clearly been made by humans. South of there, in Blackwater Draw, elegantly fashioned spear points, some about the size of the palm of your hand, turned up in the 1930s. The spear points had fluting and were large enough to fell Ice Age animals.

Clovis First, as it was called, was the one and only accepted explanation of initial human arrival and subsequent expansion throughout North and South America. To be taken seriously, any artifact of human culture had to be dated after those found at Clovis.

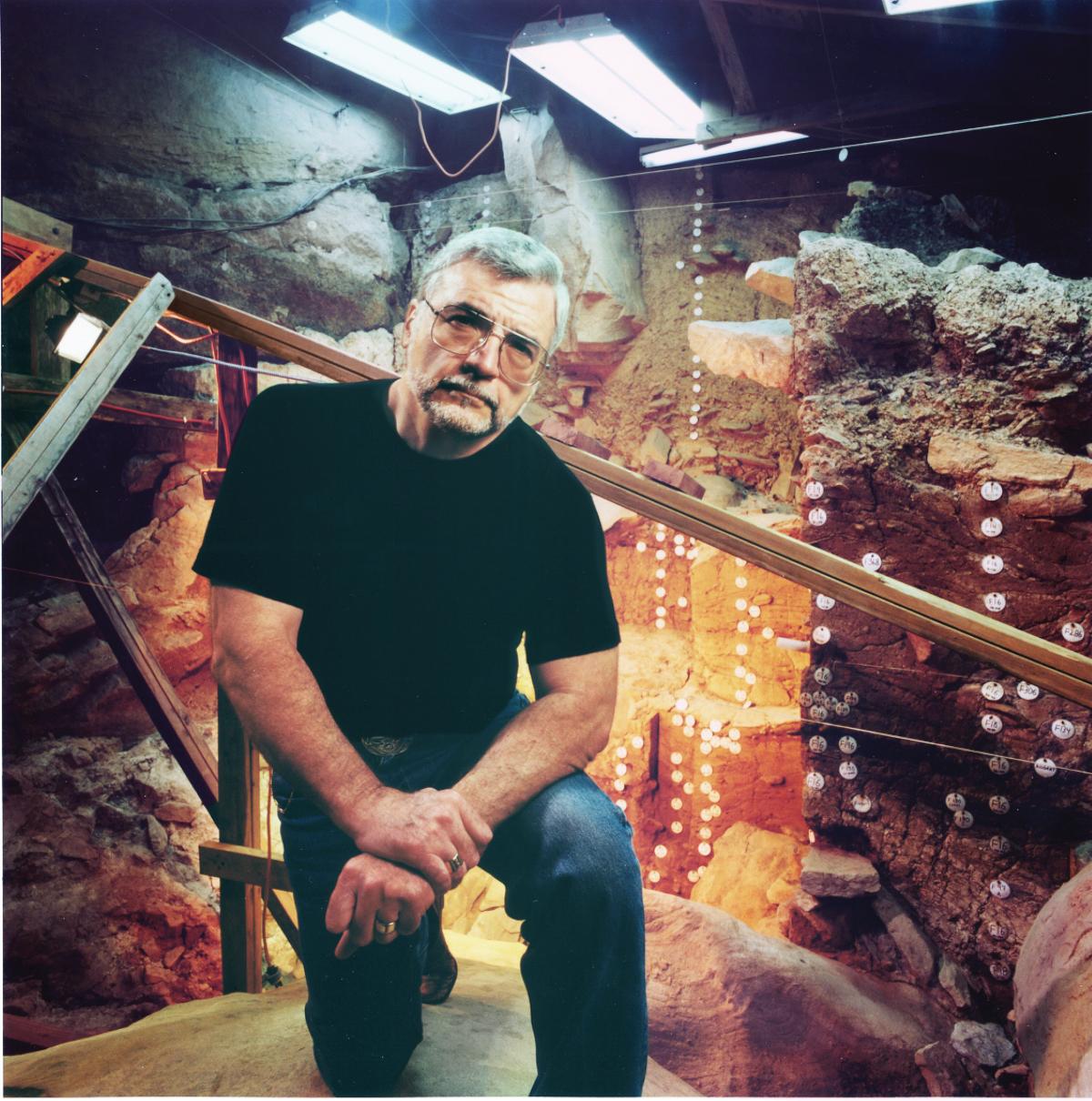

I remember learning all this in introductory archaeology at a college in southeastern Pennsylvania. Little did I or my professors know that a couple hundred miles away, at a place called Meadowcroft, not far from Pittsburgh, an archaeological dig led by James Adovasio was finding evidence that would cast the primacy of Clovis Man completely in doubt and produce major challenges for existing theories of how the first human beings arrived in North America.

It all started one day in 1955 when Albert Miller, a farmer, conservationist, and amateur historian was out hiking on his property. While passing a steep cliffside aerie with a distinctive rock overhang that yielded a naturally occurring shelter, he noticed a groundhog slip down a hole. Upon closer inspection, Miller found bones near the entrance of the hole. More than likely, the groundhog had dug up the bones and deposited them there.

Miller wondered what else lay beneath that patch of soil. He fetched a shovel and a screen, then started digging. Very quickly he unearthed a flint knife and some burned bones. Already familiar with rock shelters in western Pennsylvania, he knew to expect Indian artifacts. His own interests and experiences had trained him to look for such things.

As a young man, he had been a pilot and an accomplished aerial photographer. An interest in conservation led to a project in which he planted trees on land that had been disrupted by mining. His own farm he turned into a wildlife habitat. Yet he was also fascinated by manmade things such as antiques, but not in the usual way. “Some people are interested in that chair,” he once said of an antique. “I’m interested in the people who sat in it.”

Miller quickly realized that the land around the rock shelter was possibly significant, so he stopped digging. Instead of exploiting the site, he selflessly became its protector. The rock overhang, he realized, might easily attract hikers looking for shelter, who might happen onto evidence of something going on here, just as he had, and feel compelled to dig. To ward off potential looters, he covered the hole and hid it from view.

The site called for professional attention, and he was willing to wait until the right archaeologists came along. For almost twenty years, the discovery remained a closely guarded secret. When Miller encountered someone he thought trustworthy who might be able to connect him to the right archaeologists, he took that person into his confidence. One such person was Phil Jack, a historian of colonial America at the state college in California, Pennsylvania.

In the meantime, Miller pursued another project of historical interest, founding the Meadowcroft Museum of Rural Life on land near the rock shelter. For this reconstructed nineteenth-century village, he and his brother Delvin—a legend in harness racing—restored old cabins, a schoolhouse, a church, a barbershop, a covered bridge, and a railroad car. The museum, which was run by a board, came to own the land with the rock shelter.

In the early seventies, a young archaeologist named James Adovasio was hired by the University of Pittsburgh. He put out the word among colleagues that he would be interested in hearing about any sites near the Iron City that might be appropriate for teaching students the meticulous techniques needed to excavate archaeological digs. He got a call from Jack, the historian at the state college, who told him about Meadowcroft.

Adovasio visited Albert Miller, and they hit it off. Miller realized he had found the archaeologist with the appropriate skills to dig below the rock shelter. After Adovasio received permission from Meadowcroft’s board, he and his students began working at the site. They were joined by teams of geologists, paleontologists, climatologists, and other experts in ancient plants, pollen, and seeds. They used trowels as if they were scalpels and even razor blades to ever so gently remove soil covering the floor of the rock shelter, layer by layer, or in the lingo of a dig, horizon by horizon. The strata beneath the spot where decades earlier Miller had spied the groundhog were uncommonly intact.

The crew chief was David T. Clark, a former U.S. marine and an “utter genius with a trowel,” writes Adovasio. Precise in his work and uncompromising in his standards, Clark was said to have taught his colleagues so well that they could hear it when their tools scratched another microlayer. Climate and stratigraphic expert Joel Gunn was another character in the lineup, someone the crew came to know and fear for his Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde personalities. The archaeologists liked to get their hands dirty. They were more comfortable, Adovasio once observed, sitting in a “front-end loader or a roadside saloon than at the Princeton Club in a Hepplewhite chair.”

When the project began in June of 1973, the team expected to dig for about three or four feet before hitting bedrock, which, of course, would be sterile in terms of human activityand thus mark the end of their work there. But, even so, students would get excellent experience, comparable to that offered by other western Pennsylvania rock shelters, going back in time perhaps three thousand years. The first human artifacts they discovered were aluminum beer cans. Lower down they found steel cans, followed by glass beer bottles, and then colonial-era glass.

By the next summer, the team had gone through ever more successive layers of parallel stratification, reaching a depth of ten feet. Surprised at being able to continue deeper, but not yet finding anything unexpected, the students cataloged every point encountered (early field use of computers assisted in this) and duly noted remains of ancient hearths. Archaic points unearthed that summer resembled others found in the same region, dating back ten thousand years.

What the archaeologists encountered next would have disheartened any amateur who had endeavored to dig this deep: rocks. But Adovasio and his team recognized this for what it was, a spall—boulders that had fallen from the rock shelter’s roof thousands of years ago. They dug onward. Breaking through the spall, they began encountering the unexpected and the unknown.

Because of the stability of the site—Meadowcroft Rockshelter is nestled in Morgantown-Connellsville sandstone about 300 million years old and held high above the constantly eroding waters from nearby Cross Creek—the team surmised from the undisturbed strata that they were finding artifacts more than 12,000 calendar years old. Even without radiocarbon dating (which was used later on), they knew they were entering the realm of pre-Clovis.

Among the points they now encountered was one about three inches in length and lanceolate in shape, with no fluting. This was unlike any Clovis point and did not closely resemble anything previously discovered in North America. Later dubbed the Miller Lanceolate Projectile Point in honor of Albert Miller, it was proof that sophisticated toolmakers were in this region long before craftsmen at the Clovis site were fashioning their tools. The lesson was clear: Clovis was not first. One and all members of Adovasio’s team repaired to a nearby watering hole to discuss, celebrate, and allow it all to sink in.

Beneath the level where the Miller point was found, however, there was still more: fire pits, baskets, and cordage. While excavating the strata making up the “Deep Hole” they found a finished lithic tool later called the Mungai knife, which would be the oldest human artifact found at the site, dating back 16,000 years. The oldest findings at Meadowcroft, then, predated by thousands of years the time when many believed that giant sheets of glacial ice had shifted to make it possible for humans to cross the land bridge from Asia and descend through an ice-free corridor. Radiocarbon dating at the Smithsonian Institution confirmed their age.

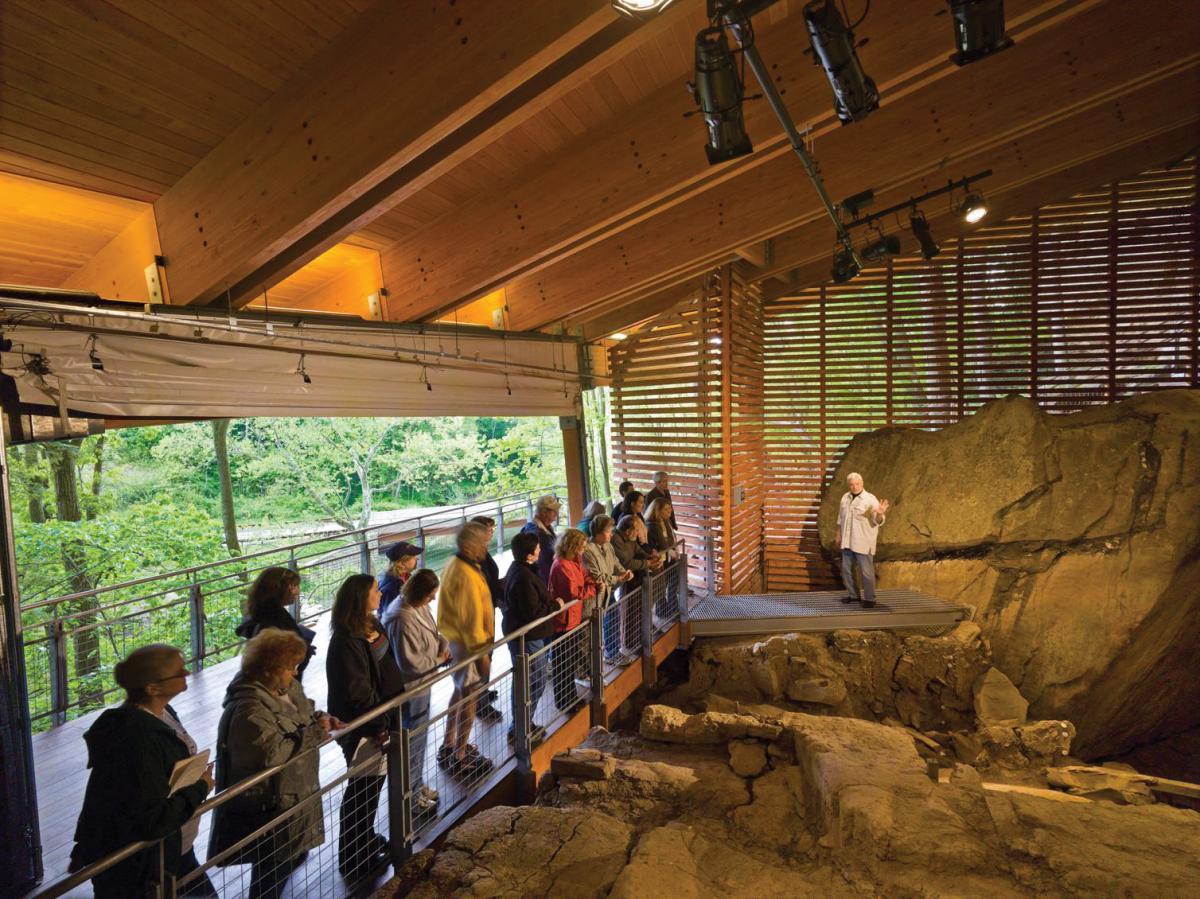

Visitors to Meadowcroft today can peer into the dig site from a platform within the rock shelter. Tags on the boulders correspond to the horizons from which artifacts had been taken. There are eleven strata and many microlayers, covering the times of George Washington back to 16,000 years ago. Throughout antiquity and into modern times, the rock shelter was part of the marked landscape. Anyone traveling along Cross Creek would have immediately recognized it as a good place to camp for a few days or weeks.

Jim Ulery, a retired geologist, who helps interpret the NEH-funded public programs at Meadowcroft, and other knowledgeable guides at the rock shelter take visitors through the chronology of geologic events. Over a period of thousands of years the grain-by-grain attrition of the sandstone falling from the roof provided the stratification of the floor of the shelter, which consequently rose continuously. Those layers of stratification formed in a natural trough, oriented north to south, in the Birmingham shale making up the shelter’s floor, which kept the layers intact and protected them from any kind of water erosion. The north-south orientation of the natural trough also afforded further protection from prevailing east winds.

Some sense of the events of the later Pleistocene is definitely a big help during a visit to the site as you gaze across the valley sculpted by Cross Creek. About 70,000 years ago, the stream left the rock shelter high and dry as it continued shaping the valley below. Then sometime, perhaps twenty thousand years ago, hunters, travelers, foragers, and collectors of chert and jasper started using the shelter regularly, a human rhythm there that continued until the moment Adovasio’s crew blocked off the area and removed their first trowel full of dirt. In all, ten thousand artifacts significant to human culture were recovered from the dig, as well as 956,000 animal bones and 1.4 million plant remains.

The findings at Meadowcroft had to be defended, however, long after the last artifact, soil sample, or molluscan remains were lifted from the Deep Hole. At conferences, in papers, and even a few drinking establishments, Adovasio has seen his team’s findings tested against professional criticism. With careers at stake, the debate has been, at times, quite heated. The esteemed archaeologist Vance Haynes, a committed Clovis Firster, argued that the cultural artifacts at Meadowcroft must have been contaminated by seepage from other strata, thereby giving them false pre-Clovis radiocarbon dates. Adovasio deflected this objection by explaining that the calcium carbonate signature—left from the remains of mollusks—was present in all strata behind the drip line, or the tip of the shelter’s roof. If there had been any groundwater seepage from any surrounding springs, the calcium carbonate signature would have been erased.

Ulery likes to remind visitors that a third of the shelter still needs to be worked on. Adovasio left a significant part of the pit unexcavated. This decision was both selfless and reminiscent of Albert Miller’s decision not to dig any further in 1955. Ulery casts a meaningful gaze at any children on the observation platform as he explains that Adovasio wanted to wait for better technology to be available before finishing the job, in hopes that future generations of archaeologists might learn even more from the site than his crew already has.

The question still nags, Who were the first humans to arrive on the continent and when did they come? During the last ice age there was a brief window of opportunity for humans from Siberia to cross the land bridge, probably about 13,000 to 14,000 years ago. Before that, closer to the glacial maximum, the icescape may have been a treacherous expanse of jagged frozen forms—unforgiving to man and beast. There would have been little for the nomads to hunt along the way, and any food they could have brought with them would have been depleted before they finished the trek. After that window, temperatures toward the end of the last ice age would have warmed enough for the land bridge to disappear beneath the sea.

So, for most of the time, it was either too dangerous or simply impossible to cross the land bridge. But there should have been a short window of opportunity between the too-cold and too-warm periods. Was it possible for the peopling of the continent to occur in such a short span of time? That is, would it have been possible for relatively small bands to cross the land bridge and within half a millennium or so reach the southern tip of South America? And what about the finds at Meadowcroft and elsewhere that predate the land bridge crossing in the first place?

Some Native Americans put little stock in what is often called archaeology’s greatest mystery. Aren’t they, they ask, the original inhabitants of North and South America? As it happens, many Indian creation myths describe the arrival of humans to the western hemisphere by sea, an idea that is increasingly gaining credence. Evidence found along the western coast, especially in California’s Channel Islands and a site in southern Chile—Monte Verde—appears to support the possibility that a “kelp highway” helped bring the first Americans to these continents. Another theory even speculates that the first arrivals came on the other side of the continent, at a time when frozen northern Atlantic waters would have been passable by foot and by boat from an overpopulated area in what is today southwestern France. This group was part of the Solutrean Culture there, and their spear points resemble Clovis points. Dennis Stanford, archaeologist at the National Museum of Natural History, has become the leading exponent of this theory. In fact, the three theories are not mutually exclusive. Discoveries at Meadowcroft and at other sites in Virginia, South Carolina, and Florida all compel further speculation.

On a recent chilly evening, as the light at Meadowcroft began to wane after the last tour of the rock shelter, Jim Ulery considered the possibilities, then shook his head inconclusively. A retired geologist, a scientist, he is loath to jump to conclusions. So, we stood there quietly, peering down the dark hole and wondering, like Albert Miller and Jim Adovasio before us, what lessons further digging might yield.