Cool is still cool. The word, the emotional style, and that whole flavor of cultural cachet remains ascendant after more than half a century.

It is, according to linguistic anthropologist Robert L. Moore, the most popular slang term of approval in English. Moore says cool is a counterword, which is a term whose meaning has broadened far beyond its original denotation.

For a millennium or so, cool has meant low in temperature, and temperature itself has long been a metaphor for psychological and emotional states (a cool reception, hotheaded). Chaucer, the Oxford English Dictionary tells us, used cool to describe someone’s wit, Shakespeare to say, “More than cool reason ever comprehends.”

But starting around the 1930s, cool began appearing in American English as an extremely casual expression to mean something like ‘intensely good.’ This usage also distinguished the speaker, italicizing their apartness from mainstream culture.

As its popularity grew, cool’s range of possible meanings exploded. Pity the lexicographer who now has to enumerate all the qualities collecting in the hidden folds of cool: self-possessed, disengaged, quietly disdainful, morally good, intellectually assured, aesthetically rewarding, physically attractive, fashionable, and on and on.

Cool as a multipurpose slang word grew prevalent in the fifties and sixties, Moore argues, displacing swell and then outshowing countless other informal superlatives such as groovy, smooth, awesome, phat, sweet, just to name a few. Along the way, however, it has become much more than a word to be broken down and defined. It is practically a way of life.

Where did it start? What were its original components? And what, specifically, about that feeling of being transported above the small-time pettiness of the everyday, that liberating and wonderful air of amazement that would be sense number one if I were to write my own subjective definition of cool?

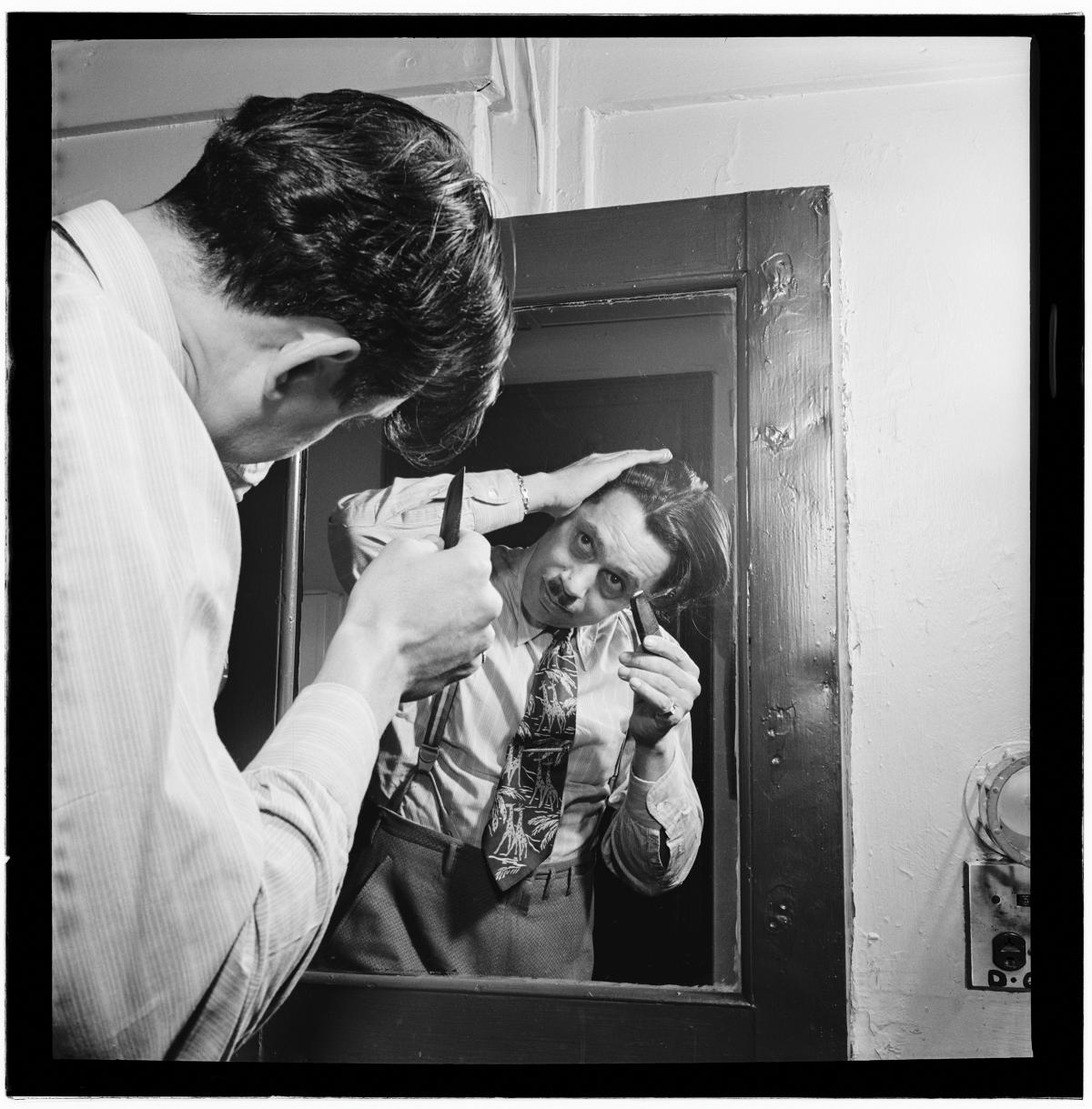

Walking into the neon-lit entrance of an exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery called “American Cool,” I examined the glamorous photos of musicians and movie stars in search of just that. The wall text instructed me that it was not the intention of curators Joel Dinerstein and Frank H. Goodyear to substitute their personal opinion for objective criteria in saying who was cool and who was not.

For my part, I decided to let my opinions lead the way as I moved from portrait to portrait, enjoying the excellent photography, though with an occasional raised eyebrow. Woody Guthrie, seriously? Then I found a pair that, arranged side by side, clearly begged for a judicial finding of cool or not cool.

On one side was Billie Holiday, before her striking physical decline. On the other was John Wayne, not in a cowboy hat but a fancy suit, hair slicked back, and smoking a cigarette.

Now, it almost goes without saying that John Wayne is cool. See Stagecoach, The Quiet Man, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and about a hundred other movies. But then why was I standing there, in the middle of a gallery of images from the 1950s, feeling dubious? Maybe it was Wayne’s suit jacket, the fussy three-point handkerchief in his breast pocket, the burning cigarette or the squinched right eye. If this image was cool, it was a fully socialized form of cool, the kind found in living rooms and at dinner parties. Swell? Maybe. But cool? I wasn’t so sure.

Even before I read the wall text telling me that Duke Ellington once called Holiday “the essence of cool,” I’m taking notes on the dark background of the picture, its velvety depth, the metaphysical pitch of the image, black from frame to frame but lit up by this haloed figure of a woman mid-song, filling the night with music your ears are straining to hear, as if you could name this tune just by looking really hard.

Next, I tally up three ingredients that my vague sense of history tells me are essential to cool at this point in time: Cool is urban; it is strongly associated with jazz; and it has something to do with race.

In a word, cool is black. Or, to be more accurate, there was a historical period in the evolution of the modern concept of cool when it seemed to be a property, largely but not exclusively, of African Americans.

Moore cites an early instance of cool in its slang form in Zora Neale Hurston’s 1935 collection Mules and Men, in which a man talks about his “box” or guitar: “Ah don’t go nowhere unless I take my box wid me. . . . And what make it so cool, Ah don’t go nowhere unless I play it.”

If African-American slang is the cradle of the new kind of cool, then jazz culture was its nursemaid. Popular American music was already quite friendly to the vernacular, but swing-style jazz went so far as to turn language into a self-conscious plaything. Starting in 1938, Cab Calloway began publishing his “Hepster’s Dictionary,” a pamphlet explaining that “jive talk is now an everyday part of the English language. Its usage is now accepted in the movies, on the stage, and in the song products of Tin Pan Alley.”

Subverting the usual method of explaining unusual words in more familiar language, the “Hepster’s Dictionary” was the un-Webster’s. To be unhep was to be “not wise to the jive, said of an icky, a Jeff, a square.” A square was an “unhep person (see icky; Jeff).” And an icky was “one who is not hip, a stupid person.” A Jeff was “a pest, a bore, an icky.”

What jazz did to American slang can also be seen in The Cool School: Writing from America’s Hip Underground, edited by Glenn O’Brien. This new volume from Library of America boasts several beautiful pieces of writing from musicians whose memoirs, usually completed with the help of professional writers, are particularly rich in sociolinguistic and literary history. From the 1940s onward, they record a vast number of moments when race and culture shaped a new set of psychological postures that have come to seem broadly American.

In the 1946 memoir Really the Blues, the Jewish saxophonist and clarinetist Mezz Mezzrow tells the story of his transformation from a young hoodlum, growing up on the streets of Chicago, to a bona fide jazzman. Following Calloway’s lead, Mezzrow took more than a passing interest in slang.

The panic was on. When we bust in on our pals we found them all kipping in one scraggy room, practically sleeping in layers. They should of had the SRO sign up. Eddie Condon was out scooting around town with Red McKenzie, trying to scare up some work. There wasn’t a gas-meter between them all, and they couldn’t remember when they’d greased their chops last. “Wait’ll you get a load of this burg—don’t lose it,” Tesch mumbled in his signifying way, cocking his sorrowful eyes over those hornrimmed cheeters.

A popular sensation that also caught the eye of a number of scholars, Really the Blues was described by the journal Phylon as “a lurid sonata of four movements: boy, man, musician, lexicographer.” Readers who checked Mezzrow’s glossary learned that a gas-meter was a quarter, kipping was sleeping, and greasing your chops was another phrase for eating. Mezzrow and his cowriter Bernard Wolfe received fan mail from Henry Miller (also represented in The Cool School), who said, “The passages that deal with the new language of the Blacks might have been written by Professor Henry L. Mencken himself.”

The linguistic aspect of cool was more than a question of learning the right lingo. Language was a central metaphor for what it meant to be transformed by black culture and music. “I was maneuvering for a new language that would make me shout out loud and romp onto glory,” wrote Mezzrow. “What I needed was the vocabulary.”

Babs Gonzales called himself the “creator of the bebop language,” having written a dictionary of bebop about as long as Calloway’s dictionary of jive. His memoir, I Paid My Dues, excerpted in The Cool School, tells the fascinating story of his rise from young hustler—paperboy, delivery boy for the local numbers game, teenaged publicist—to professional musician.

Graduating high school with good grades, Gonzales listens as the principal talks of equality and the American dream. Then, persuaded by his mother, he briefly pursues a square life, looking for a job at Bamberger’s department store, then at one of the big insurance companies, and so on. The experience was life-altering: “I would be allowed to take the tests, etc., but I was always told to come back in two weeks. It took me two months to realize the game “whitey” was playing, as I saw dumb ofay boys with ‘D’ average grades working and laughing at me waiting around offices.”

Deciding that show business was his “thing,” after all, Gonzales moved to Los Angeles, where he donned a turban and adopted the name Rahm Singh, getting more respect as a result. “Ofays in the neighborhood ‘bowed’ to me because they thought I was an ‘Indian’.”

An ofay, as Cab Calloway defined it, was a white person, though the band leader left out the oft-repeated (but doubtful) story that it came from the pig Latin for foe. There are a lot of foes in the conventional sense in these jazz memoirs: racist club owners, lying producers, and even some fellow musicians. In I Paid My Dues, Gonzales recalls Charlie Parker offering him a ride uptown in a taxicab, but then sticking him with the fare. In The Cool School, an excerpt from Miles Davis’s memoir recalls the young musician, then a student at Juilliard, wandering Manhattan in search of Bird, who was prone to show up for gigs at the last minute and address his band in a mock British accent.

Anatole Broyard’s stylish “A Portrait of the Hipster,” rightly included in The Cool School, also takes in the new aesthetic through its language, italicizing numerous words for the benefit of neophytes and outsiders. Broyard did not in this essay use the word cool. Nor does the matter of race come up, except when editor O’Brien says in his preface that “Norman Mailer defined the hipster as white Negro. Anatole Broyard was the flip side, the Negro white.”

Broyard was, indeed, African American but more or less denied it, even as rumors of his racial ancestry trailed him; fittingly, his 1948 essay is a study in ambiguity. The hipster, in his rendering, is the bebop version of cool: detached, sophisticated, a “keeper of enigmas, ironical pedagogue, a self-appointed exegete.” Broyard was limning a social type whose defining mannerisms sounded like gestural poetry, life as literary performance art.

Near the mid-century point, cool was catching on big time. In 1947, the Charlie Parker Quartet recorded its album Cool Blues. A year later, the New Yorker explained, “The bebop people have a language of their own. . . . Their expressions of approval include ‘cool!’” And, in 1949, Miles Davis recorded The Birth of the Cool, pioneering a style of jazz that ironically would come to be associated with white people and the West Coast. In 1951, Broyard revisited his essay on the hipster, in an essay in Commentary called “Keep Cool, Man.” Here he described cool as a byproduct of the Negro’s “contact with white society.”

There is another narrative of cool, well told in American Cool: Constructing a Twentieth-Century Emotional Style, that describes emotional detachment as part of a broader revision of Victorian standards. Race and music play no significant role, while modern psychology, especially in the workplace and, later, among parents and children, rewrites earlier scripts for childhood development, marriage, and socialization.

Along the way, emotional intensity becomes the anti-ideal. Fear, anger, and jealousy are tagged as obstacles to becoming well-adjusted adults, workers, and spouses. From Frederick Taylor’s scientific management, in which happy workers are presumed to be more productive, to Dr. Spock’s advice that children be taught to control their temper, the new thinking looks to save the mature adult from becoming a slave to his or her passions.

Stearns does not see this emotional style as particularly associated with African Americans. Quite the opposite. The few mentions of African-American culture in American Cool discuss the heated verbal style of black politics as a counterexample to mainstream cool, which Stearns attributes to the broad middle class, with a major caveat that his is “not a full study of the larger and more diverse national experience.”

Still, there is much to learn from Stearns’s research. In the same period when FDR said Americans had nothing to fear but fear itself, American parents were told that “their main job” was to “prevent fears” and teach their children to vent their fears by voicing them. Jealousy and anger were targeted as bad emotions. The jealous friend and spouse became a common foil in light fiction. Where Victorians saw righteous potential in anger, twentieth-century labor experts saw the angry manager as his own worst enemy: “It is of the utmost importance that the foreman remain cool.”

This is not the same as the slang term cool, and yet it is semantically indistinguishable from what Mezzrow has in mind when he described a man who is “cool and suave on the outside but with a heart full of evil.” A difference that is frequently mentioned is knowingness. A person who is really cool, in the slang sense, knows he’s cool, and may even flaunt it.

One author who turns up in The Cool School and in Moore’s linguistic research is John Clellon Holmes, who, among other accomplishments, popularized the term beat in a New York Times Magazine article in 1952 called “This Is the Beat Generation.” (Five years later, after Sputnik, Herb Caen tweaked the term by adding the Russian suffix -nik.) Holmes also wrote the novel Go, which includes a fitting description (quoted by Moore) of not only something that is cool but of how, in the presence of cool, we are drawn to figuring out what makes cool cool.

As the main character Hobbes sits with his girlfriend in a jazz club, he is explaining what is cool about the music until their attention turns elsewhere.

“When the music is cool, it’s pleasant, somewhat meditative and without tension. Everything before, you see, just last year, was ‘crazy,’ ‘frantic,’ ‘gone.’ Now, everybody is acting cool, unemotional, withdrawn. . . . But, look here, that guy coming to that table is ‘cool’!”

And it was true. The man he indicated so perfectly epitomized everything that might conceivably be meant by the term that for ten minutes Hobbes could not take his eyes off him.

Wraithlike, this person glided among the tables wearily, followed by a six-foot, supple redhead in a green print dress, and a sallow, wrinkled little hustler. . . . The “cool” man wore a wide flat brimmed slouch hat that he would not remove, and a tan drape suit that seemed to wilt at his thighs. The stringy hair on his neck protruded over a soft collar, and his dark, oily face was an expressionless mask. He moved with a huge exhaustion, as though sleep walking, and his lethargy was so consummate that it seemed to accelerate the universe around him. He sprawled at the table between the redhead and the other fellow, his head sunk into his palms, the brim of his zoot hat lowered just far enough so that no light from the bandstand could reach him. He became particularly immobile during the hottest music, as though it was a personal challenge to his somnambulism on the part of the musicians.

Talking about cool became a journalistic parlor game in the 1950s. The phrase cool cat, for example, which shows up little before this, quickly spreads from music publications such as Billboard and Metronome to On the Road by Jack Kerouac. In 1959, it is being explained to intellectuals in Encounter; in 1960, it’s in Life magazine.

The personification of cool, however, continued to be the hipster. Norman Mailer, a close reader of Anatole Broyard, was clearly influenced by Broyard’s essays on the subject, but made the connection to black culture even more explicit in “The White Negro.”

Mailer’s essay is a manifesto of sorts, against conformity, against large organizations, modern society, squares, and anyone else helping to uphold the big lie of American life. He spoke for those who, having lived through World War II, now understood that all could die at any second. Humanity had proven itself a great collective murderer, and the modern state was its greatest weapon. White people, Mailer tried to show, were thus forced into the condition of black people who had lived “on the margin between totalitarianism and democracy for two centuries.”

Today the caricature of the hipster is a hirsute Brooklynite who spends too much on food; in Mailer’s mind the hipster was a white person who had been transformed by recent history and the example of black people into a “philosophical psychopath.”

The Negro knew “in the cells of his existence that life was war, nothing but war.” So, he lives for the present, as does the hipster who, according to Mailer, has “absorbed the existentialist synapses of the Negro.”

Pleasure-seeking frees the hipster from the expectations of square society, but it’s a cheerless sort of hedonism. “To be cool is to be equipped,” wrote Mailer, “and if you are equipped it is more difficult for the next cat who comes along to put you down.” Cool is now assertive, hot-blooded even, and the counterword seems to contain its opposite. The essay ends with a vision of an all-out race war convulsing the United States.

Among those who criticized Mailer, James Baldwin, who did not appreciate the way Mailer eroticized black people, considered the essay “downright impenetrable.” Given the controversy it generated, the circumstances of its writing are especially interesting. Biographer J. Michael Lennon says the essay grew out of “Lipton’s Journal,” a diary of thoughts Mailer had been keeping for a few years. Lipton was no fictional character, but a jesting reference to the marijuana tea that Mailer imbibed before sitting down to write.

It is generally believed that it is not until the sixties that cool goes viral, as we would say. But before it does, Leroi Jones (aka Amiri Baraka) takes up its meaning in his 1963 history of blues and jazz, Blues People. For Jones, the obvious context for a discussion of cool is the recent history of cool jazz and the longer history of African-American inequality. More or less a beatnik at the time, Jones was already a provocateur, although his take on cool could be described as conventional by today’s standards.

Cool jazz began with Miles Davis, who, Jones points out, “went into a virtual eclipse of popularity during the high point of the cool style’s success.” Perhaps Davis’s personal problems were to blame, but Jones complains that more than once he has read articles calling Miles Davis “a bad imitation” of the white West Coast trumpeter Chet Baker, the embodiment of cool jazz success. If anything, Jones said, it was the other way around.

The greater irony, however, for Jones was that cool jazz “seemed to represent almost exactly the opposite of what cool as a term of social philosophy had been given to mean.” For black people, to be cool was to be “calm, even unimpressed, by what horror the world might daily propose.” Cool was a quietly rebellious response to the history of slavery and post-Civil War injustices. “The term was never meant to connote the tepid new popular music of the white middle-brow middle class. On the contrary, it was exactly this America that one was supposed to ‘be cool’ in the face of.”

By this point, however, cool was well-noticed and recorded. In 1961, Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged, mentioned cool jazz and added a new sense to its old definition of cool: “mastery of the latest in approved technique and style.” A few years later, according to Moore, cool outpaces swell, until then the most prominent slang term of approval going back to the teens and twenties.

As I walked through the exhibition, the images of cool increasingly came from areas of American life far removed from jazz. And more and more of the cool faces were not black: Lauren Bacall, James Dean, Bruce Springsteen, Steve Jobs. In retrospect, of course, they’re all cool. Even Woody Guthrie, who in the 1940s was everything cool was not: white, rural, and folksy.

Linguists have a term for insisting that a word must always mean what it once meant. It’s called the etymological fallacy. It’s a fallacy because meanings change over time, just as cool has gone from referring to a certain temperature to a word my eight-year-old son uses to describe his new BMX bike. And yet words also come bearing history, emitting scents picked up on the roads they’ve traveled. Cool in its slang form is certainly an example of this, carrying an invisible statement of origins, reminding us of the treasures of jazz, black culture generally, and the difficult history of integration.

It also reminds us of another function of slang, one elucidated recently by Michael Adams in his book Slang: The People’s Poetry. Slang is creative, aesthetically interesting, and rich in meta-commentary, some of which becomes hard to discern just a few years later, less so perhaps in the case of a word like cool, which is still readily used and readily understood, but at times can be a little hard to nail down.

*This article was updated on July 29, 2014. A paraphrase of a piece of wall text in the "American Cool" exhibit was rewritten to better reflect the curators’ intentions. And the subsequent sentence was revised.