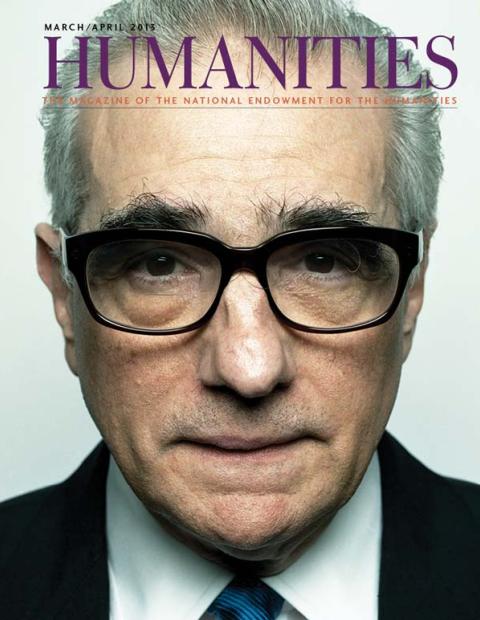

Even as a kid, Martin Scorsese, the 2013 Jefferson Lecturer, was blurring the line between entertainment and art. Growing up in Queens and on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, he was taken by his parents to the movies and became a fan of westerns. After the family bought a TV in 1948, some quirk of local programming allowed him to see Paisanand The Bicycle Thief and he became a fan of Italian neorealist cinema.

His passion for film history is well known, and so is his interest in history, period.The Gangs of New York recalls downtown thugs who ran the streets around the time of the Civil War. The Age of Innocence recalls the Gilded Age of New York’s Four Hundred. The Aviator, Raging Bull, and Goodfellas draw on nonfiction sources and span decades.

Like many thinkers of a historical bent, Scorsese has a passion for authentic details and for preservation of cultural resources. With grants from the Film Foundation, which Scorsese established in 1990, more than five hundred films have been painstakingly restored and rereleased.

And what about Scorsese’s own place within the history of our culture? His movies have helped elevate filmmaking to a position of equality with literature and other arts in the American tradition. His preoccupation with American character and the moral contortions it undergoes in the search for fame, glory, and pleasure places him deep in a dark critical tradition stretching back to Poe and Melville and Fitzgerald. A former seminarian, Scorsese has studied the savage side of our moral nature, even as his films entertain the possibility of our redemption.

The moral and dramatic possibilities of popular entertainment were definitely on the mind of Harriet Beecher Stowe when she wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, whose publishing history tells us a great deal about American literacy and the shifting biases of the reading public. Randall Fuller discusses Barbara Hochman’s book on the subject.

Carl Sandburg also found readers among all classes of Americans, though,as Danny Heitman explains, his critical reputation has never equaled his popular appeal. The translators Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky went from critical darlings to the best-seller list when Oprah endorsed their version of Anna Karenina. They have recently finished translating Tolstoy’s last novel, and talked with Kevin Mahnken about the art and ironies of translation.

As we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, NEH and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History are giving out DVD sets of NEH-supported documentaries about civil rights history to five hundred communities across the country. One of the four, Slavery by Another Name, is discussed in this issue by Lynette Holloway, who explores how Douglas A. Blackmon’s book on post-Emancipation labor bondage became a notable documentary in the hands of director Sam Pollard.