A question lingering in every issue of HUMANITIES is how we remember. It’s a question of legacy, of how humanity’s thoughts and words and deeds are recalled or forgotten by succeeding generations. Individuals ask to be remembered, but a writer may record his or her own life for posterity. There are two such writers in this issue, both diarists fortunate to have understood that semiprivate events in their own lives would echo historically.

One of the diarists, Julien Green, happened to write about the other’s funeral: “I had the impression of a profound sadness, tearing, racing through the chapel, as if Kessler, rising, had grabbed on to us, like a drowning man who seizes a boat full of people. . . . When one carried away the casket, there was a kind of general distress, I cannot express it any other way; one tore poor Kessler from his friends.”

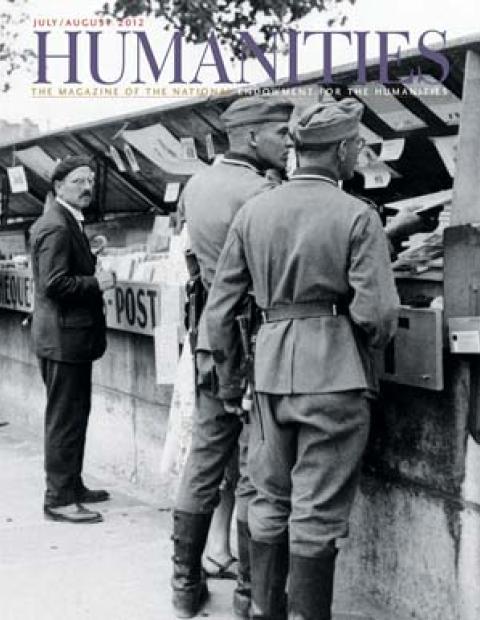

Among important American writers, Green has to be one of the most obscure, at least to American readers. A U.S. citizen born and raised in France, he wrote mostly in French and even became the first non-French citizen to be elected to the Académie Française. As Francis-Noël Thomas shows, Green’s diaries of the fall of France make for a unique and revealing record of what surrender, occupation, and exile mean not just to an individual but a whole society.

Kessler was Count Harry Kessler. Another diarist, he was also man of the arts: a patron, a curator, an organizer, a connoisseur of culture and people. And one person to whom he was very good was Friedrich Nietzsche. Although he came into the philosopher’s life only after Nietzsche had lost his mind, Kessler was intimately involved in plans for Nietzsche’s archives and a grandiose memorial. In his valiant efforts to work with Nietzsche’s anti-Semitic sister, Kessler appears to us at the doorstep of a lost opportunity to preserve the philosopher’s work from significant corruption.

James Agee also bore witness to historical events, as a journalist to the ravages of the Great Depression and as a critic to the rise of cinema as a major new art form. His talent for scene making, Danny Heitman shows, was visible in his magazine work, his screenwriting, and his fiction.

One wonders how a writer like Agee would have described the public spectacle of street theater and religious observance in the medieval Corpus Christi plays from York, England. With Agee being unavailable, we asked James Williford to essay on the macabre pageantry of the plays and their performance. His account, I think, will prove memorable.