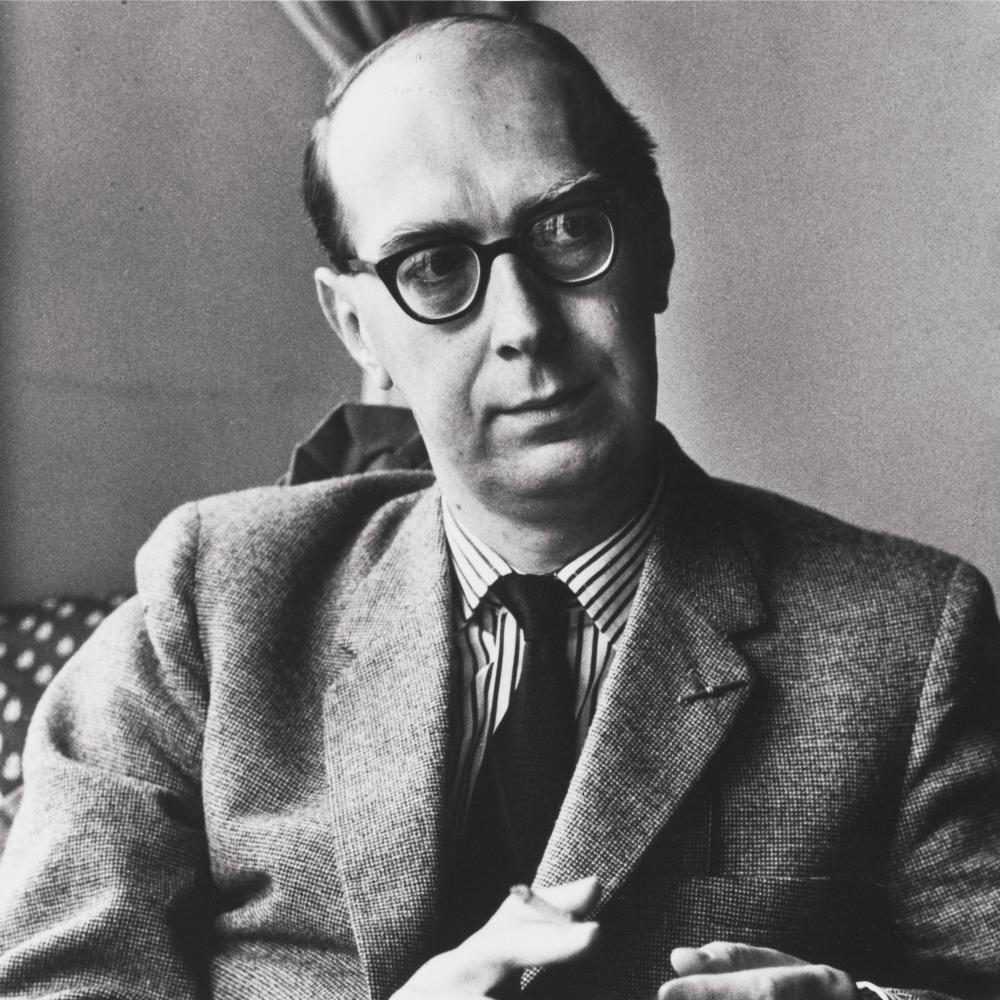

Philip Larkin started writing poems in 1938 when he was fifteen or sixteen and very nearly stopped about ten years before he died at sixty-three. His reputation, during his lifetime, was based almost entirely on three collections published at intervals of approximately ten years: The Less Deceived (1955), The Whitsun Weddings (1964), and High Windows (1974). Together they contain eighty-five poems, all but a few of them under forty lines. He said in an interview that he never wanted to “be a poet,” and he did not follow the established routine of people who did want to “be poets.” He didn’t give readings or lectures, was never a poet-in-residence at a university, never taught, rarely gave interviews, generally stayed away from literary circles, stayed away from London, did not work at maintaining a network of editors and publishers, did not have an agent or a publicist, and finally stopped writing poems. For him, to “be a poet” meant spending a lot of time doing things he considered inimical to writing poems. “I don’t want to go around pretending to be me.”

Beginning in 1955, he lived in Hull, where he was appointed university librarian, and he stayed there for the rest of his life. The University of Hull underwent a major expansion during his nearly thirty-year tenure; he was closely involved in the planning, design, and construction of two new library buildings. At the end of his career, he was directing a staff of over a hundred. When he first appeared in Who’s Who in 1959, he did not mention he was a poet or even a writer.

All three of his mature collections enjoyed unusual success not just with critics but with the reading public. After the publication of High Windows, he became, in the words of biographer Andrew Motion, “a national monument.” It was just at that point that he essentially stopped writing poems. In his 1982 interview with

The Paris Review, he was asked if he really completed only about three poems a year, as his publication history suggested. He began his answer with a surprising evasion: “It’s unlikely I shall write any more poems,” and in fact during his final three years, he seems to have written just seven poems, a total of thirty-seven lines. He answered an earlier question about his writing routine by saying, “Anything I say about writing poems is bound to be retrospective, because in fact I’ve written very little since moving into this house, or since High Windows, or since 1974, whichever way you like to put it.” Being forced to move out of the apartment in which he wrote High Windows was a trauma from which he seems never fully to have recovered, although there must have been deeper reasons behind his long and rarely interrupted dry period. When he gave The Paris Review interview, he was probably the most widely read and most highly respected living poet writing in English.

As a mature poet, Larkin is unheroic in his subject matter and in his attitude. In his poems, he characteristically presents himself as a passive observer of ordinary events and ordinary experiences: prominently, disappointment, failure, regret, fear of death. Even when he addresses historic subjects—war or the erosion of a culture—he does so from the perspective of an ordinary person with no active role to play: “It seems, just now, / To be happening so very fast; / . . . / And that will be England gone.” His astonishing poem on the First World War and the world it destroyed, “MCMXIV,” is a prime example of how a traditionally heroic subject becomes the observation of a single, passive speaker—an extraordinary articulation of what is presented as ordinary observation.

Larkin put considerable effort into establishing his persona, not merely as the represented speaker of his poems but as a real-life working poet. He presented himself as a full-time librarian who, at the end of a day’s work, after preparing and eating his solitary dinner and washing up, wrote unpretentious and “unliterary” poems, based on common experiences and the emotions they prompted. He maintained that there was nothing extraordinary about what he did. He once said of the experience that inspired “The Whitsun Weddings,” “You couldn’t be on that train without feeling the young lives all starting off, and that just for a moment you were touching them. . . . It was wonderful, a marvelous afternoon. It only needed writing down. Anybody could have done it.”

This is, of course, sheer fantasy. “Anybody” might have had a broadly similar emotional response to the wedding parties boarding the train at a half-dozen stops between Hulland London, but the claim that anybody could have written the poem is a secondary artifact of the mask that Larkin fashioned for himself. His own testimony and documents in his own hand show that he completed it only with great difficulty. In The Paris Reviewinterview, he said, “I began it sometime in the summer of 1957. After three pages I dropped it. . . . I picked it up again, in March 1958, and worked on it till October, when it was finished.” Shortly after finishing it, he wrote to Monica Jones, his companion of thirty-five years, “I’ve never known anything resist me so! . . . I have just hammered it to an end, but really out of sheer desperation to see this fiendish 8th verse in some kind of order.” His manuscript workbook supports what he says in this letter.

His cover was blown in 1988, three years after his death, when one of his literary executors, Anthony Thwaite, edited the first Collected Poems. Despite Larkin’s saying that the order of the poems in his published collections had been carefully worked out to create a deliberate sequence, Thwaite presented the poems in chronological order, adding sixty-one previously unpublished poems—some unfinished—to the first section, “Poems 1946–83,” and twenty-two to the second, “Early Poems 1938–45,” almost doubling the number of poems Larkin was known to have written. About a half-dozen of these newly published poems were, in the opinion of some readers, as good or even better than poems Larkin had published in his lifetime, but the additional material diluted the effect of the original collections. In 2003, Thwaite, tacitly responding to vociferous criticism of the first Collected Poems, published a second version, which omits many of the unpublished poems—and all of the unpublished juvenilia—and restores what he calls “Larkin’s own deliberate ordering of his poems in each successive book.”

It remains a matter of dispute whether, on balance, the publication of so many poems that Larkin himself left unpublished served his reputation. It certainly destroyed the persona he had cultivated for most of a lifetime, and for this Larkin himself is chiefly responsible. He lacked the resolution and the ruthlessness necessary either to destroy his unpublished work or unambiguously to instruct his executors to do so. He left his trustees, Monica Jones and his lawyer, Terence Wheldon, all his work, published or unpublished, with “full rights” to publish what he had left unpublished, but in the next clause of his will he directed that his unpublished writings and his manuscripts be destroyed unread. A further clause directs his trustees to consult his literary executors “in all matters concerned with the publication of my unpublished manuscripts.” In his Paris Review interview, he was asked, “Do you throw away a lot of poems?” He answered, “Some poems didn’t get finished. Some didn’t get published. I never throw anything away.”

His inclinations were, in almost equal measure, to be confiding and to be deceptive. During his lifetime, he misrepresented his whole career as a poet in the same way he misrepresented the writing of “The Whitsun Weddings.” After his death, he was shown to be—perhaps by his own design—something quite different from the provincial librarian who, after work, wrote several of the best English-language poems of the second half of the twentieth century. The appearance of the poems he held back from publication revealed someone far more credible: a working poet whose impressive successes were sometimes hard won and whose commitment to writing was unremitting and lay at the core of his identity. When he found he could no longer write poems, he was devastated.

Clive James claimed that people who attain the measure of fame that Larkin achieved (or suffered) have no private lives. Nevertheless, Larkin’s oral request that the approximately thirty volumes of his diaries be destroyed was honored. A large volume of his letters, however, was published in 1992 and set off a cascade of negative comment from shocked readers that, for a few years, threatened to diminish his standing—at least in some academic circles—as a poet.

That tempest seems to be over; the culture police have not managed to bury his achievements as a poet under his politically incorrect views, his apparent misogyny, or his duplicity toward his lovers. Now, some twenty-six years after his death, his complete poems have been published in an exemplary scholarly edition by Archie Burnett, a director of the Editorial Institute and professor of English at Boston University.

Whatever damage Larkin’s reputation may have suffered from hostile commentators since the publication of his letters, he is exceptionally fortunate to have Professor Burnett as the editor of his complete poems. It is an indication of his standing as the greatest English poet of his generation and a vote of confidence in his enduring interest to scholarly readers that this edition of his poems has been published. It is the first posthumous collection that really is—to use a distinction that Larkin himself made—a collection rather than a selection and the first to be edited by a professional (and highly accomplished) textual critic. The Complete Poems is a work of technical scholarship that is directed in the first instance to scholars. But Larkin is, of course, celebrated for extending what he said was the achievement of John Betjeman, “a rejection of modernism,” which involved restoring “direct intelligible communication to poetry.” For him, poetry should be as directly intelligible as speech. “Writing poetry is playing off the natural rhythms and word-order of speech against the artificialities of rhythm and meter.”

It was Eliot who gave the modernist poetic movement its charter in the sentence, “Poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult,” and it was Betjeman who was to bypass the whole light industry of critical exegesis that had grown up round this fatal phrase by demonstrating that a direct relation with the reading public could be established by anyone able to be moving and memorable.

What Larkin said of Betjeman’s relation with the reading public is true of his own. “In this century English poetry,” Larkin maintained, “went off on a loop-line that took it away from the general reader.” He offers several “reasons.” The first, “the aberration of modernism, that blighted all the arts,” simply begs the question; the second, “the emergence of English literature as an academic subject, and the consequent demand for a kind of poetry that needed elucidation” reflects his own rejection of modernism and his antipathy for academic criticism.

It is arguable, Larkin adds, “that Betjeman was the writer who knocked over the ‘No Road Through to Real Life’ signs that the new tradition had erected, and who restored direct intelligible communication to poetry.” Arguable, but Larkin might as well be talking about himself here. Betjeman remains largely a British—even a specifically English—writer; Larkin, for all his dramatized provincialism, has been embraced by the whole English-speaking world.

Larkin never modified either his disdain for academic “elucidation” or his disapproval of “the emergence of English literature as an academic subject.” He maintained that “there’s not much to say about my work. When you’ve read a poem, that’s it, it’s all quite clear what it means,” but he has been well served by technical scholarship. First, in his own lifetime—and with his cooperation—by B. C. Bloomfield’s bibliography (1979; revised and enlarged 2002) and now by Archie Burnett’s edition of the complete poems.

Few nonacademic readers will be drawn to a complete edition of Larkin’s poems or even see the need for one. For most of his large readership, his achievement will be defined by two dozen or so poems: “Church Going”; “The Whitsun Weddings”; “An Arundel Tomb”; “High Windows”; “The Old Fools”; “Going, Going”; “This Be the Verse”; “Annus Mirabilis”; “Vers de Société”; and “Aubade” prominently among them. Some of his audience will remember individual lines such as “’Nothing, like something, happens anywhere’”; “What will survive of us is love”; “Days are where we live”; “Never such innocence again”; and, inevitably, “Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three”; and “They fuck you up, your mum and dad,” in some cases without even being aware that Larkin wrote them.

In an interview with John Haffenden published in 1981, Larkin said he was delighted when a friend asked him if he knew a poem ending, “What will survive of us is love.” Larkin commented, “It suggested the poem [“An Arundel Tomb”] was making its way without me. I like them to do that.”

Burnett’s edition includes “all of Larkin’s poems whose texts are accessible.” These texts, meticulously checked against primary sources, are offered under four rubrics: the four volumes published in Larkin’s lifetime “preserved as collections” (117 poems); other poems published in the poet’s lifetime but not included in any collection (36 poems in order of publication date); poems not published in the poet’s lifetime (403 poems in chronological order determined by the date on which Larkin stopped working on each poem); and undated or approximately dated poems (10 poems).

Of the total, then, of 566 poems (some as brief as two lines), 413 are poems Larkin did not publish himself. Fewer than a dozen of these poems could conceivably make their way without Larkin; for the approximately four hundred remaining poems, their only claim to anyone’s interest is that they were written by Philip Larkin. He said himself, “If one is interested in a poet one wants all of his poems in the order they were published, not a selection according to his own idea reshuffled to conceal how bad he was when he started, the whole with lots of alterations to suit the latest fashion in adjectives.”

Larkin’s reference to “poems in the order they were published” should not be taken to suggest that he opposed the publication of previously unpublished material. As a librarian, he argued that “unpublished work, unfinished work, even notes towards unwritten work all contribute to our knowledge of a writer’s intentions.” Burnett’s Complete Poems inevitably offers a large number of poems that are neither unusual—“extraordinary” was Larkin’s term for poems that make an immediate impression because they are so different from what we have grown used to—nor good.

Presumably the unpublished and untitled four-line poem of October 1943 (from a letter to Kingsley Amis) in which the speaker proclaims, “I would give all I possess” to engage “the prettiest girl in Warwick King’s High School” contributes to our knowledge of Larkin’s poetic intentions. I find it difficult, however, to see how it helps our understanding of “High Windows” or “Annus Mirabilis,” poems that might be thought to share some of the unpublished poem’s subject matter.

Good poems, Larkin said, “are [normally] surprising rather than extraordinary, keeping the power to inflict their tiny pristine shock long after they have become familiar.” At least a few dozen of Philip Larkin’s poems are “good” by this standard. And it is because of these good poems that he has received the attention of textual scholarship although, along the way, such scholarship offers unexceptional and mediocre poems a kind of artificial life support. What, then, does Burnett’s Complete Poems do for the poet’s good poems?

First of all, it offers accurate texts. I have not conducted an independent examination of primary sources, but Burnett brings a professional textual critic’s disciplined attention to Larkin’s poems in manuscript, typescript, and published forms. He says he has corrected “a scattering of errors” in the Collected Poems (1988) and 139 errors in six different categories (wording, punctuation, letter-case, word division, font, and format), in previously published texts of early poems and juvenilia. He offers variant wordings for the first time, and improved dating of the poems, showing in many cases durations of years between start and finish. Most important to the readers that Larkin was eager to have, Burnett offers commentaries and glosses for terms that are likely to need glossing. Let me offer an example from “MCMXIV.” This sixteen-line poem in four stanzas is, as Larkin has pointed out, a single “sentence” lacking a main verb: It is also something like a collage of photographs on the day that the First World War began, offering an image of the last full day of a world that the war destroyed. It makes reference to “The Oval,” to “Villa Park,” to tin advertisements for cocoa, and “twist”; to “Domesday lines” in the haunting phrase “fields / Shadowing Domesday lines / Under wheat’s restless silence.” Most readers of this poem today, perhaps especially Americans, are unlikely to know what any of these four terms means. I once consulted my best map of London (six inches to one mile) and found The Oval in Kennington, which I guessed was a sporting ground; I failed to find Villa Park and guessed it was another sporting ground. I had no idea what “twist” might be, although I assumed it was a consumer product of some sort, and I missed the reference to Domesday lines altogether.

Burnett glosses each of these terms (and glosses similar references in every one of Larkin’s poems). I guessed correctly that The Oval was a sporting ground, but it makes a difference to know, as Burnett’s gloss informs me, that cricket matches have been played there since 1846. It isn’t surprising that I could not find Villa Park on my map of London since it is the “home of Aston Villa, a football club in Birmingham.” Twist, I learned for the first time, is “tobacco shaped into a thick cord,” and Domesday lines are “visible boundaries of landed properties in the record of the Great Inquisition or Survey of the lands of England (from the eleventh century onwards).”

“MCMXIV” delivers its pristine shock long after it becomes familiar even if the reader is ignorant of what these terms mean, but it puts the poem in sharper focus to know precisely what they mean, and it contributes to the sense of a world’s coming to an end to know that the “Domesday lines” go back as far as the eleventh century.

The only unfortunate feature of the Complete Poems is a production decision that I assume was out of Burnett’s hands. The poems are not given a fresh page even in the case of previously collected poems said to be “preserved as collections.” “Church Going” from The Less Deceived (1955) begins on the same page as the final thirteen lines of “No Road” and all of “Wires.” “MCMXIV” does not have a page to itself. There is no indication that the four-line “Llandovery” is a separate poem. The book runs to some 726 pages, and it would have been much longer if every short poem had its own page, but the decision to deprive even the previously collected poems (each of which started on a fresh page in the collections) is a design blunder.

The commonplace poems preserved here may contribute to our knowledge of Larkin’s poetic intentions, but it is the sharp focus in which Burnett’s edition puts Larkin’s enduring poems that gives this edition its value for the general reader, who was always Larkin’s primary audience. It is a shame that the page design does not reflect the literary focus the commentary achieves.

Whatever Larkin’s personal faults may have been, they do not compromise a poem like “MCMXIV” in the least. We may recall a line from Auden’s elegy for William Butler Yeats: “You were silly like us; your gift survived it all.” Larkin had his personal failings as does everyone, but a few dozen times in his forty-plus years as a poet he wrote moving and memorable poems that now inflict their pristine shock in a pristine edition. These poems have made it without him in that mysterious way that the best poems both reflect their writer’s life and rise above it. In his lifetime, Larkin hesitated to acknowledge how much of himself he put into his poems, how much writing poems meant to him. His usual idiom was self-deprecatory. What has survived of him in this edition of his poems is love.