When you work on magazines, reading and rereading articles, you become alert to weird little coincidences. Three stories in a single issue will mention corduroy or the Napoleonic Code or Ernest Hemingway, and you may even consider removing one of the references to avoid the unintended suggestion that everything relates to corduroy, the Napoleonic Code, or Hemingway. But if you’re like me, you resist the urge, wondering to yourself, Maybe everything is about corduroy.

In this issue the unlikely point of convergence is Oberlin, Ohio. This bucolic college town was home to the Anti-Saloon League, the organization that lobbied state and federal legislators to prohibit the sale of alcohol throughout the United States. Author Michael A. Lerner, a contributor to Ken Burns’s upcoming documentary, reminds us that while Prohibition was achieved through unseemly means, and led to many an unfortunate consequence, the basic idea seemed much less irrational when Americans consumed three times as much alcohol as they do today.

Before the Civil War, Oberlin was a hotbed of abolitionist sentiment and advanced racial thinking. Black men and women were welcome at Oberlin College, and the townspeople stirred to action when word spread that one of their fellow citizens was in danger of being kidnapped back into bondage. NEH research fellow Daniel J. Sharfstein tells the story of a slave-catcher, who comes to Oberlin in search of a man named Henry, armed with revolvers, handcuffs, and a roll of bills to pay off informants.

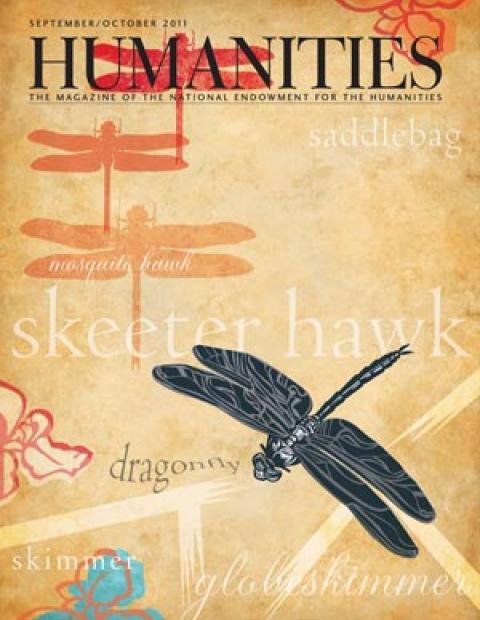

Oberlin College also happens to be the alma mater of Frederic G. Cassidy, probably the greatest American lexicographer of the twentieth century. For decades, dialectologists had made only the faintest progress toward a dictionary of American regional English, when Cassidy sketched a remarkably bold editorial plan, and was quickly appointed to make it a reality. The Dictionary of American Regional English was finally on its way. As the publication of its fifth and final volume nears, Michael Adams takes measure of this monument to the American language.

Christopher McDonough recounts a more spontaneous investigation into American culture, which he lucked into after discovering a handsome statue that once belonged to Tennessee Williams. The salty British soldier Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Pearson, a forgotten figure of the War of 1812, is the subject of another essay in this issue. Meanwhile, Amy Lifson writes about a project by the Journey Through Hallowed Ground that has middle schoolers using local archives and their own family’s records to make short films about the Civil War. What these stories have in common is a lack of any substantial connection to Oberlin, Ohio . . . at least that I know of.