The Communist crowd shot was a standby of Cold War-era newspapers, newsreels, and television broadcasts. Always in contrast to the iconography of Western individualism, East Europeans appeared as the “toiling masses” of Communist rhetoric: Throngs lined up in 1953 to see Stalin’s coffin; multitudes gathered on the main thoroughfares of Moscow, East Berlin, and Warsaw to watch soldiers, athletes, or visiting dignitaries on parade. The East Bloc’s demise in 1989 prompted similar imagery of masses breaching the Berlin Wall in 1989—jubilant for a change—crossing through Checkpoint Charlie or cheering on those who did. Lost in all of those crowds, though, were the individual lives and everyday experiences: how people ate and drank, laughed and cried, fell into and out of love, worked and played during the decades of Communist rule in the East Bloc.

The Wende Museum and Archive of the Cold War offers priceless insight into how people lived under communism, and how they came to challenge it. Some items in the museum recall the overstuffed apartments of Muscovites, replete with ceramic plates celebrating the 1980 Moscow Olympics and multivolume editions of the writings of everyone from Karl Marx to Jack London. Other items speak about the dramatic changes of the late 1980s. Take, for instance, an eight-inch plaster bust of Vladimir Lenin mass-produced in the German Democratic Republic in the 1960s. What makes this particular bust unusual is the paint job it received—in neon pink and turquoise—during protests against the Communist regime in the fall of 1989. Lenin’s figure had gone from being a ubiquitous part of East German everyday life to being a symbol of protest.

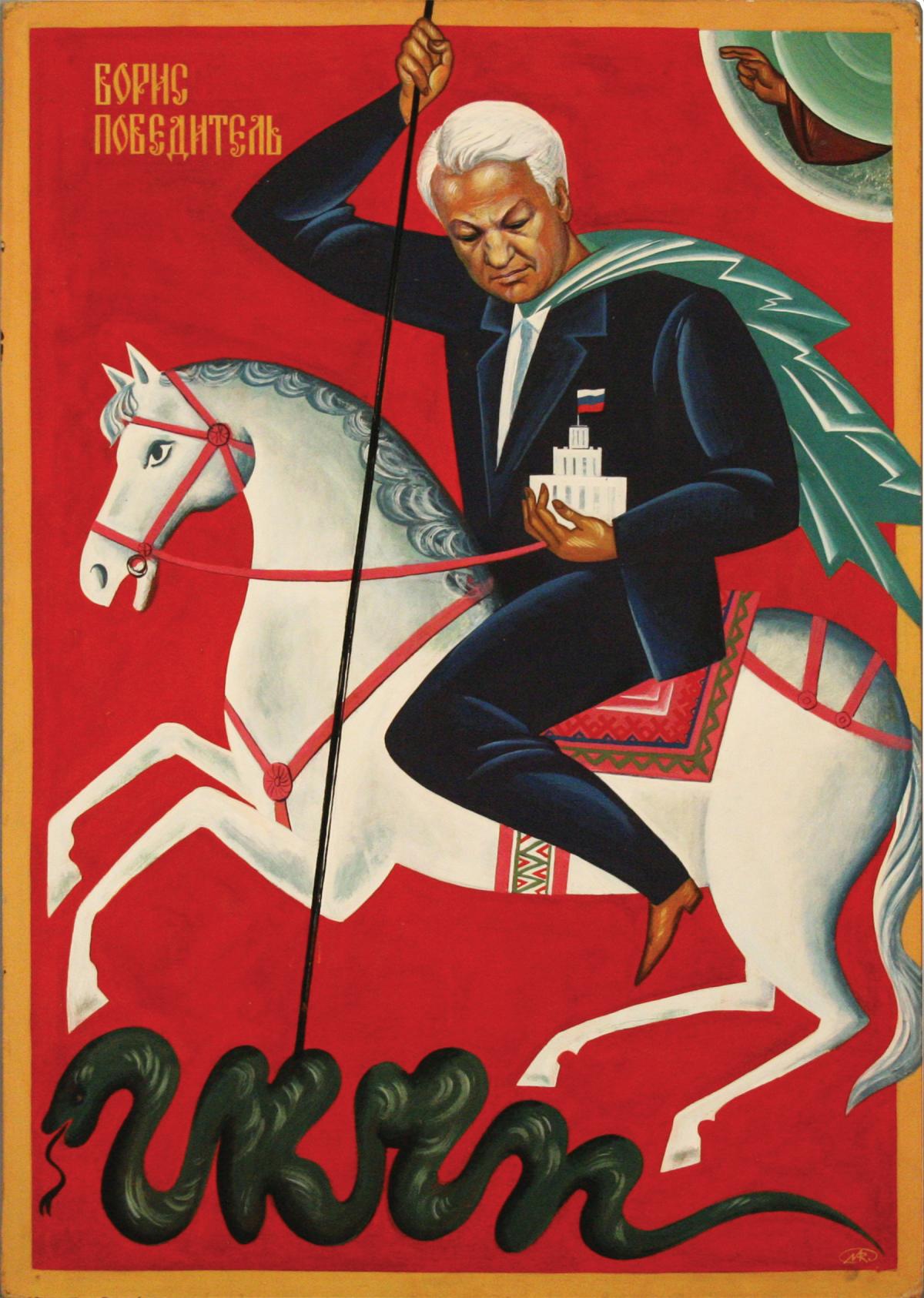

The young museum in Los Angeles County wants to tell these stories of both everyday life and dramatic change. Its 60,000 artifacts from the former East Bloc include clothes, attaché cases, posters and sports and theater programs, huge banners, tiny lapel pins, newspapers, and personal diaries.

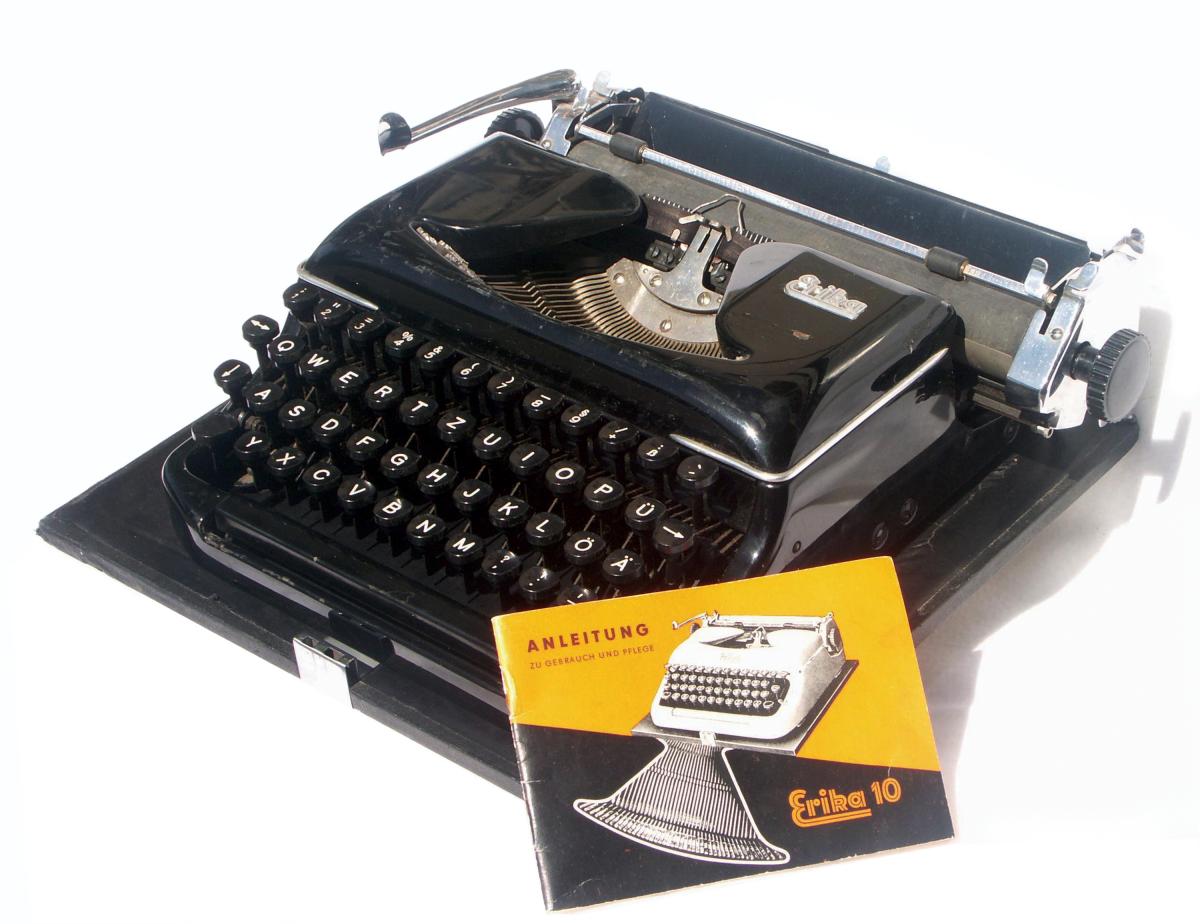

Wende is the word Germans use to describe the changes of 1989. The museum takes as its mission the chronicling of that change. About half of the artifacts, including many of the most interesting and unusual, are from the German Democratic Republic: the border guards’ logbook for November 9, 1989, the day the Wall was breached; private papers from Communist party chief Erich Honecker, and tools of the spy trade such as listening devices from Stasi, the East German secret service. Its Stasi equipment collection is so unusual that western intelligence agents have visited the museum to learn more about their erstwhile adversary.

Materials in a dozen or more languages from other parts of the East Bloc that cover everything from politics to culture to entertainment make up the rest of the collections. On display during my visit was a wall of commemorative ceramic plates inscribed in Polish, Bulgarian, Romanian, Hungarian, Russian, and German. Drawers full of pins from the USSR and all around the East Bloc sit in the storage area along with Czech radios, Soviet paintings, and shelves of factory and club scrapbooks.

The museum bears the mark of its Angeleno founder, Justinian Jampol. Only two years after graduating from UCLA, Jampol spent (by one account) a six-figure inheritance to start the museum in 2002. But it was only after the museum received a $2.9-million grant from the Arcadia Fund—closely connected to Peter Baldwin, one of his history professors from UCLA—that Jampol could really set up shop. Walking around the museum with Jampol, I got a clear sense of how he’s been able to do so much. With a strong vision in mind, he uses his energy and charisma to bring others along. But it is not just his youthful enthusiasm that shapes the museum. There’s also its unusual acquisition strategy, which included purchasing discards from Berlin libraries and even picking through piles of trash outside East German office buildings. Now in his thirties—and pursuing a doctorate in modern European history at St. Antony’s College at Oxford—Jampol is heading a museum that is moving out of its startup phase.

The result is a remarkable collection—unusual for Europe and unparalleled in the United States. On the day I visited, graduate student Manfred Zeller from the University of Bremen was browsing through fan magazines and programs of leading Soviet and East German soccer teams, including the powerhouse Moscow-Dinamo. Thrilled by his findings, he pointed to the ways in which socialist cooperation crossed with sporting competition at soccer tournaments.

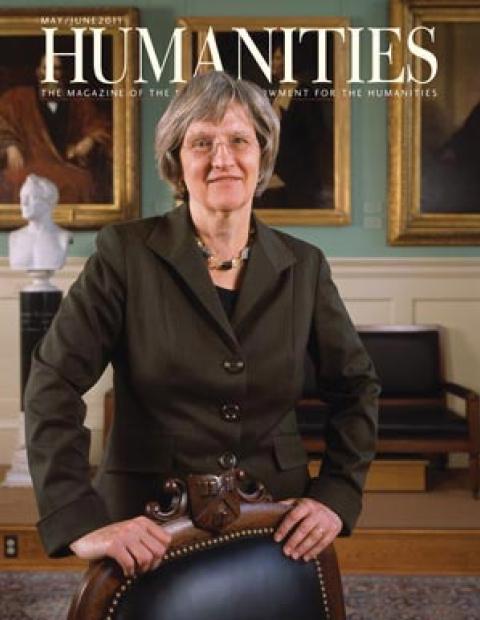

Yale medievalist Paul Freedman is a less likely researcher at the Wende, but he learned about it from a UCLA historian who had been another of Jampol’s teachers. Freedman found the museum holdings “amazing,” especially for his current research on the history of food. He singled out some menus from Honecker’s state dinners for what they reveal about “East German culinary identity . . . appropriate to a (supposedly) workers’ state.” Using Wende materials, Freedman wrote “The Discovery of the Prawn Cocktail,” an article on luxury cuisine in East Germany.

A museum devoted to the drab everyday lives of East Europeans seems especially out of place in sunny Los Angeles. But the fact that Zeller and Freedman came for research suggests it is meeting at least one of Jampol’s goals: to serve as a repository for a part of the European past that is easily forgotten—and when remembered, likely to spark heated debates. Even before the reunification of Germany, scholars in the West fought furiously over Alltagsgeschichte, the history of everyday life, which some historians argued whitewashed popular support for Nazism. Defended as an enterprise to recover and describe daily life of Germans in tumultuous times, Alltagsgeschichte flew in the face of usual German historical scholarship, more concerned with economic and political structures than with individual experiences. Critics worried that the attention on ordinary people’s experiences would omit the enormity of the Third Reich—and the role ordinary people had in it. Though that debate has receded, the politics of reunification has sparked controversies over who gets to exhibit and interpret the East European—and especially the East German—past. Being five thousand miles from Germany, Jampol says, frees his museum from these disputes and allows for a certain analytical distance. At a 2009 conference hosted by the museum and cosponsored with the German Historical Institute in Washington, for instance, historians from East and West Germany along with other scholars came together to engage in a freewheeling discussion about the material culture of German Communism—a topic that might have been difficult to hold on German soil.

Located in Culver City, far removed from Los Angeles’s many hotspots, the Wende is an unlikely tourist destination, though a hoped-for move may help increase walk-in traffic. Yet even without visiting crowds, the museum has made a place for itself in Los Angeles’s glittery and sprawling cultural world by drawing attention to world-changing events rather than everyday life. The Wende hit it big with its Wall Project, which dealt with the iconic structure of the Cold War. The Berlin Wall, the visible manifestation of Cold War divisions, showed also the conflict between Communist rule and its citizens’ aspirations for a better life. Through the 1950s, as West Germany underwent its “economic miracle,” East Germany stagnated. By 1960, as many as fifteen hundred East Germans each week departed for more prosperous West Berlin. In response, East German leaders begged Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev for a way to stanch this flow. Khrushchev eventually conceded, arguing that promises of socialism’s bright future paled in comparison with what West German capitalism had to offer in the present. One night in August 1961, East German border guards marked the occupation boundary with barbed wire; the erecting of a more solid structure began soon after. When it was completed, the Wall seemed permanent, the final division of Europe into East and West, splitting one of Europe’s great cities—not to mention many German families—in two. Yet before it turned thirty, the Wall was rendered irrelevant. Portions of the Wall still exist amid the construction sites of central Berlin, but its first purpose is long gone.

In November 2009, the Wende Museum celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the demise of the Berlin Wall with a very L.A. combination of performance and cutting-edge art. The museum made good use of the ten sections of the original wall—roughly forty feet—that it owns. (That’s the largest portion outside Germany.) Arrayed along the sidewalks of Wilshire Boulevard, the Wende’s Wall Project drew an international roster of artists, including Shepard Fairey, famous for his depiction of Barack Obama, and Thierry Noir, a Frenchman who began painting the Berlin Wall years before it came down. People from all over the world and students from local art schools joined the more famous muralists. Jampol reminded participants that this use of the Wall was in keeping with history; the side facing westward became what he called “the world’s largest mural, attracting artists from around the world whose paintings transformed the Wall into a canvas reflecting real and imagined divisions.”

On the night marking twenty years since that exuberant evening in Berlin, the divisions in Los Angeles were more real than imagined. The “Wall along Wilshire” was bisected by a temporary “Wall across Wilshire,” which closed one of the city’s major streets as a reminder of what the Wall meant to Berliners. Joined by Los Angeles politicians and German diplomats, with a special message from the mayor of Berlin, the Wende turned Wilshire Boulevard into an extravaganza of art and music. At the stroke of midnight, participating artists toppled the Wall across Wilshire.

This public art “happening” made news headlines around the world. Cristina Cuevas-Wolf, programming coordinator, proudly pulled out for me two hefty binders of clippings from across the United States and Europe, showing articles from art magazines, tabloids, and even the Wall Street Journal. The Wall Project, as Collections Manager John Elliott put it with a wry smile, “cemented our role in the community.”

Such big public events have helped the museum build stronger connections with local universities. Interns from colleges all over Los Angeles have worked there, and class visits are becoming increasingly common. Roman Koropeckyj of UCLA’s Slavic Department enthused about taking his class on Central and Eastern European cultures to the Wende last year. He was most excited for the rare chance it provided his students to see—and more important, to touch—artifacts from the cultures they were studying. Koropeckyj praised the Wende as “one of the genuine jewels in a city that has many.” His students benefited from the lessons it teaches about Eastern Europe as well as material culture. For the teacher, the museum provided a “trip down memory lane,” recalling his research in Poland in the 1970s. The setup of a Communist bureaucrat’s office at the Wende evoked Koropeckyj’s own visits to such offices, furnished in what he called “late socialist modern” in which “the cheap and the shoddy” were passed off as relative “luxury.”

So what exactly is the Wende? Is it a public art facility that has historical collections? Is it a history museum branching out into art? Is it a research collection with exhibit halls? Such questions don’t interest Jampol or his staff, who share a common vision that defies conventional categories. Even the mission statement alludes to the museum’s unusual aims; it is a “hybrid organization,” simultaneously an archive and an educational institution with a scholarly agenda.

The museum employs conservation specialists whose work is guided by the ideas of a consultant provided through an NEH preservation grant, and its volunteer “scouts” across Eastern Europe rummage through attics and flea markets for new acquisitions, which are kept in the museum’s climate-controlled storage facility in Berlin. The museum focuses on material culture, while its Historical Witness project gathers oral histories from Jampol’s fellow collectors as well as ordinary citizens in Eastern Europe and the USSR. With equipment from the film industry and interns from California State University, Long Beach, the museum has begun digitizing its collection of five thousand pedagogical films from the East German Ministry of Education. The films include schoolroom videos on hygiene and traffic safety and continuing-education programs on everything from chemistry to nursing. The museum also participates in international conversations and focuses on contributions to its local community through film series.

The museum will continue to move in all of these directions and more in the next year. Germans’ Things: Material Culture and Daily Life in East and West, a book based on the 2009 conference, is due out shortly. A revamped website featuring images of its collection is well under way. And the museum is gearing up to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the demise of the USSR in December.

The prospects for the Wende Museum might well be described by an old Soviet joke that played off Communist propaganda about socialism’s “bright future” as well as the constant rewriting of history books to fit current-day politics. As the joke went, a bright future is certain; it’s the past that keeps on changing.