It is perhaps not widely appreciated that the Cold War was actually won in the summer of 1959 by the noted lounge-chair designers Charles and Ray Eames.

It was in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park where the Los Angeles-based, husband-and-wife designer duo unleashed America’s secret weapon: a twelve-minute, seven-screen spectacle of synchronized photos, film, and music that would, in the words of its sponsor, offer irrefutable “visual proof of the abundance of American society” and, by extension, the superiority of the American Way. Modestly titled Glimpses of the USA, the multimedia barrage had been unglimpsed by its sponsors, the U.S. Information Agency, throughout its production. Even its makers had not seen the presentation in its entirety until it was tested only one night before the opening of the American National Exhibition. This film was conceived as the second half of a tense, hastily organized bilateral cultural exchange perhaps more famous as the site of then-Vice President Richard Nixon’s “Kitchen Debate” with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev.

“Glimpses of the USA” was the key feature of the exhibition’s main pavilion, a gold-anodized, Buckminster Fuller-style geodesic dome known as “The Information Machine.” After a dizzying choreography of over 2,200 images of American life, landscape, and industry filled the dome’s seven massive movie screens, the film ended with an emotional punch: a tiny vase of bouquets of forget-me-nots. In his memoir Cold War Confrontations, USIA design chief Jack Masey describes how, as the humble flowers, known as nezabudki in Russian, filled their field of vision, the ersatz audience of American diplomats, Finnish carpenters, and Russian construction workers united as one in joyful friendship, tears and “wild applause.”

Such incidents, triumphantly recounted, can make it seem that, four subsequent decades of Cold War upheavals and conflicts notwithstanding, modernism and design had, in fact, delivered on its promise of a glorious, prosperous, and well-appointed postwar future for all. If only, right?

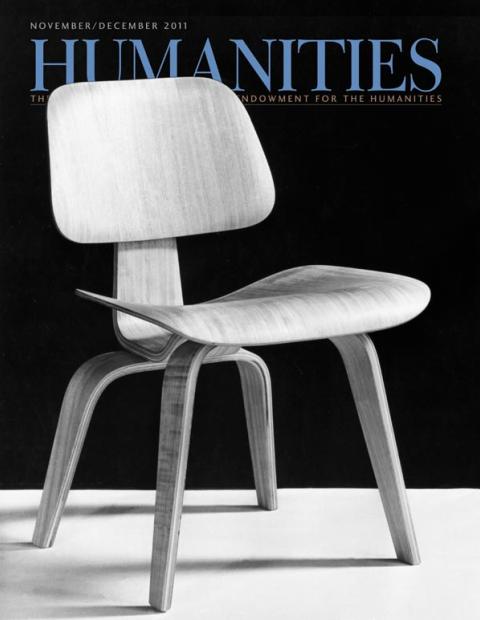

Even for the longtime admirer, it’s not so easy to figure out the best perspective to gauge the Eameses’ prodigious and far-ranging achievements. The Eameses’ towering place in American design history is as indisputable as their continued influence. Their revolutionary early furniture designs, made with techniques and materials adapted from LA’s World War II-fueled aviation industry, are sought-after classics.

The house they built themselves, in a meadow overlooking the Pacific, using only mail-order steel and industrial glass, is the icon of the midcentury modernist lifestyle. While the original 1949 house is being restored, the entire contents of its double-height living room have been transferred to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), which constructed a full-scale, indoor replica to anchor the exhibit “California Design: 1930–1965: ‘Living in a Modern Way’” through March 2012.

Eames Studio’s films, created for their own enlightenment or for government and corporate clients such as IBM, combined marketing and cutting-edge information theory with experiment and whimsy. And in their greatest triumph (or failure, or both) decades after their deaths, (Charles died in 1978, Ray in 1988), the Eames name has become the universal keyword for “modern design” on the world’s online flea market, eBay.

Throughout their own careers, whether making architecture, furniture, toys, annual reports, or films, the Eameses presented themselves as designers. And despite their forays into education, computing, and international diplomacy, that’s how they are typically seen. But calling the Eameses designers while trying to account for their polymathic legacy can be problematic, particularly if we’re picturing the designer as a lone, heroic genius: Charles Eames as the Howard Roark of American consumer capitalism. It invites many esoteric and academic questions about process, context, gender, and collaboration, which are interesting but hard to resolve. When considered from an artistic perspective, however, many of these complications evaporate. Accepting Ray and Charles Eames as artists and their studio work as art gets us away from the arbitrage over who did what and how. Plus, it enriches and deepens the contemporary understanding of their role in the culture of their time.

A new documentary, Charles + Ray Eames: The Architect and the Painter, which airs on PBS as part of the American Masters Series, makes significant progress toward an artistic appreciation of the duo. Even as they ultimately succumb to Charles’s much-discussed charisma, the filmmakers also examine Ray’s training as a painter and the vital infusion of their entire practice with her aesthetic and perceptual sensibility. Ray’s art, then, becomes a valid retort to the “age-old question” veteran Eames Studio collaborator-turned-historian John Neuhart posed many years ago, “What did Ray Eames actually do?”

Another answer is that she collected material for use and inspiration. By the time it was donated to the Library of Congress in 1989, the Eames Studio’s slide library had grown to over 320,000 images. She made meticulous arrangements of curated artworks and other objects, in spaces as small as a tabletop or as large as their living room, which fed into the studio’s work. And she orchestrated the experiential aspects of their projects—the forget-me-nots were Ray’s idea—and even of their own lives. While apparently overlooked or devalued in the design context, these practices resonate with concepts that would emerge in the contemporary art world years or even decades later, movements and genres such as installation art, performance, happenings, systems art, and relational aesthetics.

In interviews with studio colleagues, “The Architect and the Painter” also touches on the extraordinary degree of creative autonomy the Eameses enjoyed, even when they were working for ineluctably bureaucratic clients like IBM, Alcoa, and the U.S. government. The American National Exhibition tale, in which Charles refused to sign a contract, submit a storyboard, or even have their work reviewed before it was done, is the stuff of fantasy for every designer who’s had to suck it up and smile when she was asked to just make the logo bigger. But that is partly because unfettered creative freedom is so atypical of corporate communications and much closer to the process of an artist’s studio.

Eames Demetrios quoted his grandfather as saying, “If you don’t ask for people’s opinions, they don’t give them.” It’s a sentiment that dovetails with artist Roy Lichtenstein’s analysis of his 1969 collaboration with Universal to produce a film installation as part of LACMA’s Art & Technology Program:

“There is a tendency to present artists with things to do...you’re getting led by other people’s ideas.... It’s like filling orders.... There are so many things that people want you to do. I think you could fill orders and never go in your own direction. I prefer not to be led.... I like to work in my studio and let one painting lead to another.”

Eames Studio designer Deborah Sussman said Ray and Charles shunned the art label: “What we were doing was not art, because art does nothing. We solve problems.”

One of the problems they solved in 1958 was how to depict the shiny, playful future of a world full of Alcoa aluminum. And the solution was, frankly, a work of art: The Solar Do-Nothing Machine, since lost, was a tabletop-sized assemblage of painted whirligigs which was set in motion by tiny, photovoltaic-powered motors. Charles called it a toy to be experienced, not played with: “We now have a moment in time which is very precious; but this is valid only if the toy does nothing.”

The Solar Do-Nothing Machine does nothing, and it does it beautifully. It is a prettier, more whimsical, but no less sculptural version of the kinetic art Yves Tanguy or Len Lye were making around the same time.

From the late 1950s onward, this becomes a prevalent pattern for the Eameses: With their sculptural objects, their films and multimedia projects, and their exhibitions and world’s fair pavilions, their activities often paralleled contemporaneous developments in the art world, and in many cases, even prefigured them.

Experimental filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek began creating programming in 1957 for his Movie-Drome, a Fuller-style, geodesic dome cinema which he first built in 1963. And though his goal for it was unity with the cosmos, not just the Soviet Union, VanDerBeek’s Movie-Drome bore a striking resemblance in form, content and purpose to the Information Machine in Sokolniki Park.

Like the Eameses, artists created exhibitions, programming, even entire pavilions, for a steady string of world’s fairs. At Expo 58 in Brussels, the IBM Pavilion featured the Eames-produced animated film The Information Machine: Creative Man and the Data Processor. In the parabolic concrete pavilion they created for Philips Electronics, Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis projected their Poème électronique, a music, light, and image spectacle tracing mankind’s march toward peace. The Eameses designed IBM’s 1964 pavilion, and a roster of America’s most successful painters created work for the most iconic U.S. World’s Fair pavilion, Buckminster Fuller’s 1967 geodesic sphere in Montreal.

Expo70 in Osaka was both the zenith and the nadir of artist/corporate collaboration. The U.S. Pavilion displayed work from LACMA’s Art & Technology Program. Meanwhile, E.A.T., Experiments in Art & Technology, an artist/engineer collective founded by Robert Rauschenberg, executed an ambitious failure at the Pepsi Pavilion. The visionary, poorly managed project involving several dozen artists and performers and ran so far over budget that Pepsi pulled the plug after just a couple of weeks. If anything, the Eameses were making world’s fair art more successfully than the “actual” artists.

Which raises the nagging question: If so, then what? When they echoed or even anticipated the avant-garde art world so frequently, when their own creative process so often resembled that of an artist’s studio, why did the Eameses insist on not calling their work art?

One hint may be found in A Communications Primer, an educational research project and film from 1953, which historians such as Jeffrey Meikle see as a turning point in U.S. design from products to information. For the film, Ray and Charles translated the cutting-edge research on information theory from the likes of mathematicians Claude Shannon and John von Neumann into lucid, remarkably robust, animated explanations of how humans communicate. Even now, it holds up remarkably well.

The Eameses used art—specifically painting—to teach the complicated theories of human communication, but it was only one example. To the Eameses, art was only a subset of what they were trying to express: the very nature of information and communication itself, the foundation of culture and civilization. Art was important, even vital, but it was simply too small a field for the Eameses’ ambitions—at least the art of their time as they perceived it. It is only now, when the scope and purview and critical frameworks of contemporary art have expanded, that art is beginning to catch up to what Charles and Ray were doing fifty years ago.