Let’s dispense with the romance of Paris. A century ago, the City of Light was a city of lice for the artists who carved out their reputations there. The primitive conditions of their apartments and studios often meant no heat and no running water. Money for food was scarce, while disease and infestation were in abundance. A story of the painter Chaim Soutine sets the general tone. An abscess he discovered on his ear turned out to be a nest of bedbugs. “Poverty was a luxury,” said the playwright Jean Cocteau of his neighborhood of Montparnasse. The term “starving artist” was no conceit. La Vie de Bohème might be appealing on the stage of Puccini’s opera or in the pages of Henry Murger’s nineteenth-century novel of struggling artists. The real life of the Paris Bohemian was hard and unenviable.

So why did so many artists flock there from around the world? As a new PBS program called Paris: The Luminous Years asks, “Why Paris?”

Another question could be, Why does any great city, with its high rents and low standards of living, attract artists who could paint or write just about anywhere? One answer may be found in an unusual place: a theory of economics first promoted by the urbanist Jane Jacobs. Her understanding of an effect called “knowledge spillover,” which helps explain the rise of industries in certain cities, such as textile manufacturing in Birmingham, England, might also help take some of the mystery out of the magic of Paris.

First, some background on Jacobs’s theory and the history of knowledge spillover: In 1890, the economist Sir Alfred Marshall described cities as “having ideas in the air.” He recognized that the countless interactions that city dwellers have with each other on a daily basis could also have a unique effect on innovation. Such interactions were a direct result of urban density, where people live and work in a close proximity to one another. Greater density meant a higher chance of unplanned encounters and conversations, whether on the street, across the hallway, or often in the gossip of restaurants and cafés. These discussions resulted in the phenomenon of “spillover.”

Here is the remarkable thing about knowledge spillovers. If the crowd is right, people can pick up invaluable information through casual interactions in what is called a “dynamic externality”—in other words, free of charge. In exchange for struggling in the crowded city, the poorest worker could indeed be enriched by its “ideas in the air.” Through one’s own innovation, those ideas could be translated into new and better products.

Marshall and his intellectual descendants maintained that the concentration of a single industry in a city would best benefit from knowledge spillover. Some theorists even thought that urban monopolies might be best poised to take advantage of knowledge spillover. It was assumed that when interactions within companies were limited, workers would not risk sharing secrets with the competition. From this notion emerged the development of the office park, with its concentration of solitary businesses.

Yet, in 1969, in her book The Economy of Cities, Jane Jacobs offered her own theory of urban communication that updated in a significant way what is now called Marshall-Arrow-Romer externalities. Instead of concentrating single industries or even single companies, Jacobs maintained that the variety and diversity of businesses in a dense environment led to the greatest and swiftest innovations. The reasons were twofold: A cross-fertilization of ideas across different industries and a density of small firms in local competition with one another bring innovation most quickly to market. Monopolies avoid the risks of innovation and are slow to recognize new demand, but small firms can be adaptable. “Few sights are more flabbergasting than the sheer quantity and diversity of work and working places concentrated in a great city,” Jacobs wrote, and such diverse concentrations encourage the borrowing of innovations from one industry and applying them to another.

Concerning the diversity of urban influences, Jacobs was making an important point. Examples of the ideas of one industry informing another are numerous. The development of the auto industry in Detroit grew out of innovations in shipbuilding for Lake Erie, where the gasoline-powered boat was an antecedent to the automobile. New York’s financial services industry emerged from the demands and knowledge of the cotton and grain merchants trading in town. In the early 1990s, a team of researchers from Harvard, New York University, and the University of Chicago, led by Edward L. Glaeser, conducted an analysis of data sets of major industries in U.S. cities between the years 1956 and 1987. They concluded that Jacobs’s understanding of knowledge spillovers was right. A variety of activities in a dense environment stimulates the greatest innovation.

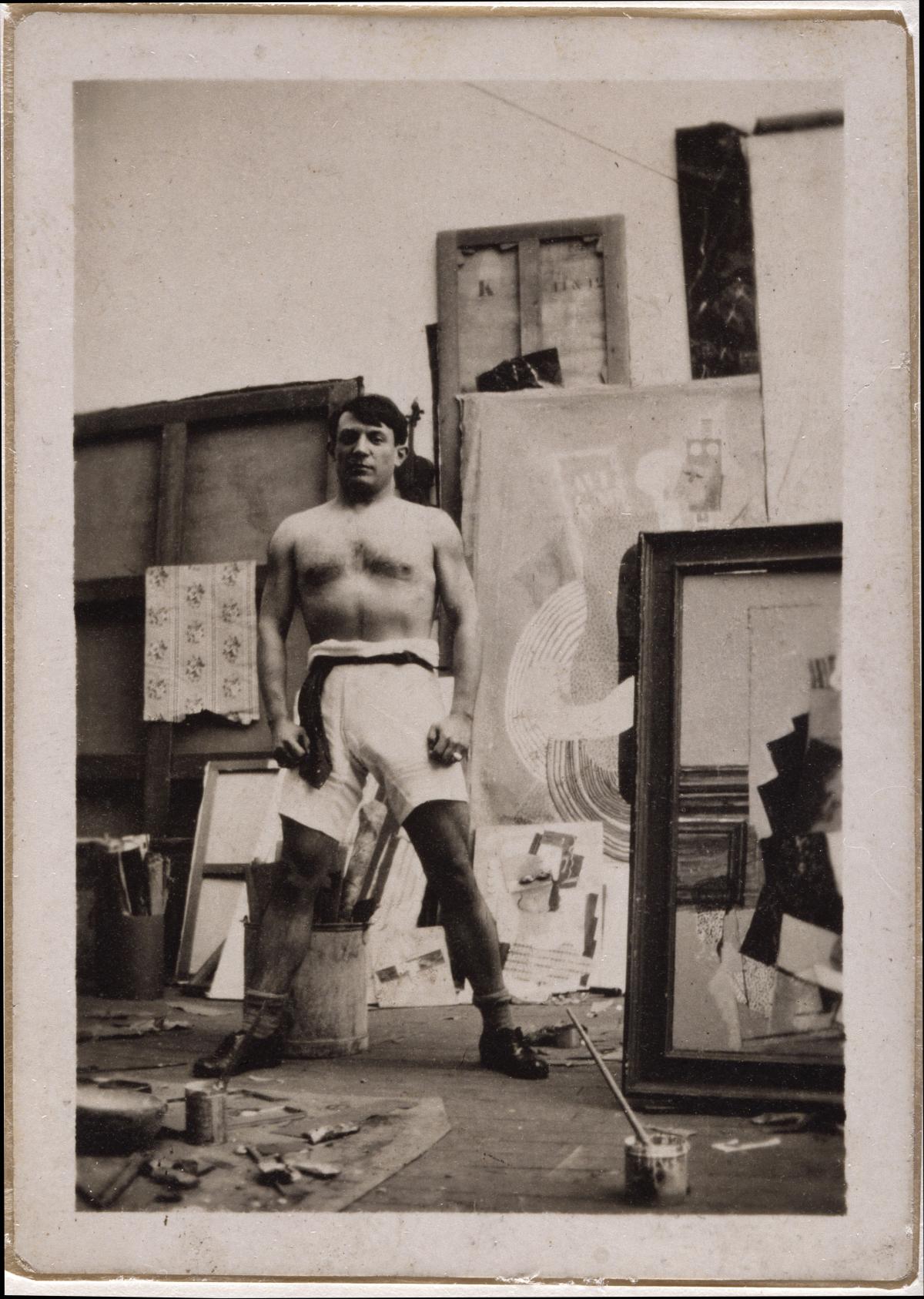

To understand how the Jacobs theory applies to the artistic life of Paris at the turn of the past century, consider the rise of Pablo Picasso. The Spanish artist was not nearly the finest painter of the Modern movement, but he was by far its most ruthless innovator.

Picasso from a young age understood the particular role that the city of Paris could play in his success. He was as calculating in determining his accommodations there and the way he moved through the city as he was in his adoption of new painting styles and techniques.

Instead of developing new textiles or faster engines, Parisian artists at the turn of the century—its Modernist innovators, anyway—worked on one thing: building a better avant-garde. Picasso determined to do this better than anyone else.

Picasso was born in the Andalusian town of Málaga in 1881. His father, José Ruiz Blasco, was a successful art teacher and painter of naturalistic scenes. He bestowed on his son a talent for applying oil on canvas, but Picasso had to go elsewhere to develop his singular sense of Modernist innovation. After spending his teen years in Barcelona and Madrid, where the prodigious painter found early success with his symbolist figures, he moved to Paris for good in 1904. He established himself in the area of Montmartre, a hill on the northern Right Bank, which had been the heart of the artistic life of the city in the 1890s. Everyone from Eugène Delacroix to Vincent Van Gogh had passed over its steep slopes. Several of the Impressionists had found a home in its circuses and cabarets. Starting in 1904, Picasso’s Paris headquarters was a hovel of a studio, without gas or electricity, known as the Bateau-Lavoir, so named for resembling the laundry washbasins used along the Seine.

“To a greater extent than any time since the Renaissance,” wrote the historian Roger Shattuck of Paris at the turn of the century, “painters, writers, and musicians lived and worked together and tried their hands at each other’s arts in an atmosphere of perpetual collaboration.” In his first decade in Paris, Picasso absorbed every drop of the city’s knowledge spillover. He especially adapted innovations from other artistic fields. From non-Western sculpture to experimental writing, music, and dance, Picasso found new ideas for his paintings.

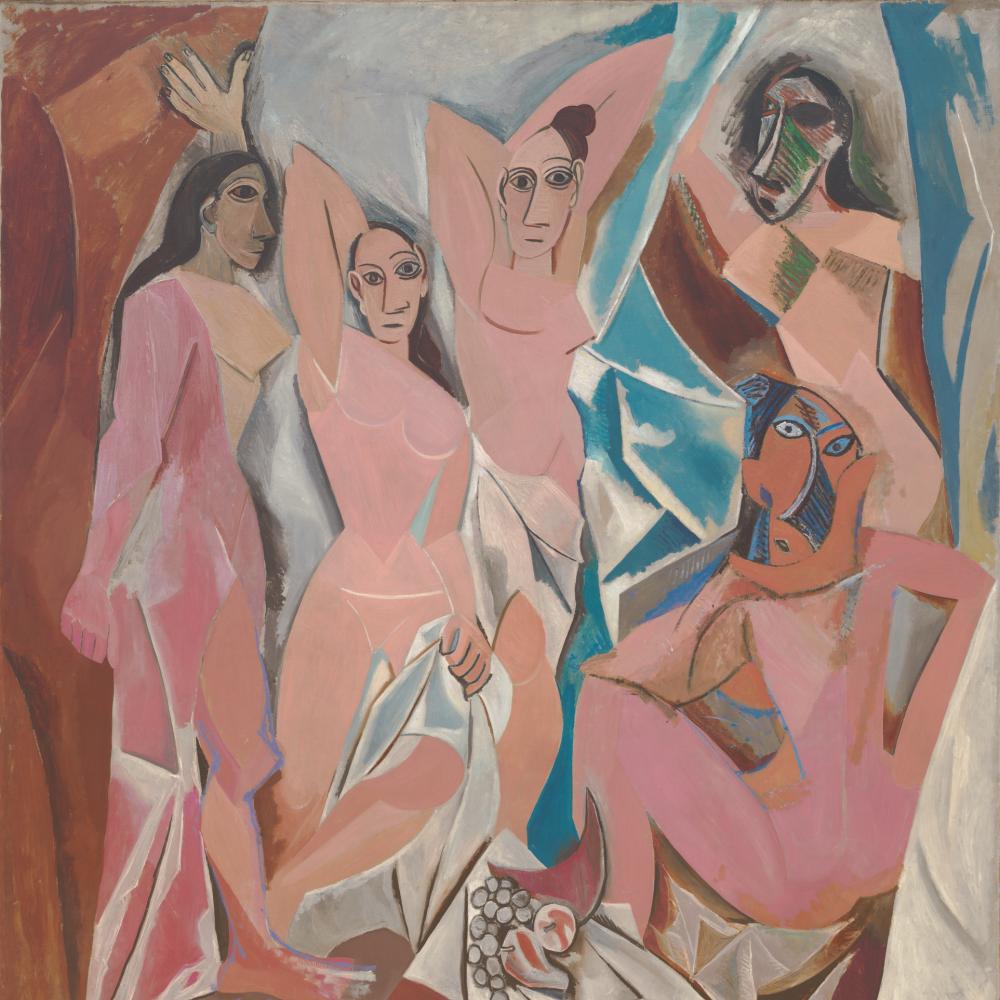

The painter’s earliest friend in Paris was the art critic and poet Max Jacob, who exposed him to the poetry of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Verlaine during some previous visits to the city. Picasso’s Blue Period of 1901–1904, in which he painted only in somber tones, was influenced by the mood of the Symbolist poets. Picasso then synthesized the singularly strange and groundbreaking Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon in 1907 by fusing African masks, which he may have seen at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, with influences from Iberian statuary and the paintings of Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and El Greco. From a further analysis of Cézanne, whose work was surveyed in the Salon d’Autumne of 1905, a year before he died, Picasso found a new way to model pictorial space. He incorporated Cézanne’s technique with the literary innovations of friends like the poet Guillaume Apollinaire and turned painting into “a form of writing,” as his dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler described the development of Analytical and Synthetic Cubism between 1908 and 1914.

The other great Cubist innovator, Georges Braque, described his relationship with Picasso as “two mountain climbers roped together.” In reality, Picasso was roped to every artistic innovator the city had on offer. Aside from Braque and his Spanish protégé Juan Gris, Picasso’s closest friends and influences in the Bateau-Lavoir were not painters. Apollinaire, Jacob, and the poet and critic André Salmon were the charter members of the Bande à Picasso. The artist even saw fit to write “au rendez-vous des poètes” in chalk on his studio door.

In 1912, Picasso made a different sort of discovery. The knowledge spillover of Montmartre was drying up just as another artist neighborhood was taking shape. Across the other side of town, connected by the new Number 12 Nord-Sud metro line but a world apart, the Left Bank neighborhood of Montparnasse was already humming with artistic activity when Picasso closed the door on Montmartre, never to return. By the time Picasso moved to Montparnasse, it had already become the new modern neighborhood, and the innovation-minded artist had no choice but to relocate. The dealer Kahnweiler found him his first space there, on the Boulevard Raspail.

Apollinaire described the emerging difference between the two neighborhoods in this way. Montmartre was “full of fake artists, eccentric industrialists, and devil-may-care opium smokers. In Montparnasse, on the other hand, you can now find the real artists, dressed in American-style clothes. You may find a few of them high on cocaine, but that doesn’t matter: the principles of most Parnassois (so called to distinguish them from the Parnassians) are opposed to the consumption of artificial paradises in any shape or form.”

By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, the picturesque charms of Montmartre had flooded the neighborhood with tourists, pleasure seekers, and painters working in the un-innovative style of Maurice Utrillo. For the old-fashioned plein-air painter, the brand-new neighborhood of Montparnasse was far less attractive—a work in progress, with wide streets and empty lots—but it was perfect for the Modernists in their studios. “It wasn’t picturesque like Montmartre. I think Montparnasse was the opposite—rather dull and unfinished,” said the art historian Kenneth Silver in an interview. Silver, who appears in Paris: The Luminous Years, is mounting an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum on Modernism between the wars, called “Chaos and Classicism.”

What it lacked in charms Montparnasse made up for with ample space for knowledge spillover. A ring of new, large cafés at the intersection of Boulevard du Montparnasse and Boulevard Raspail became the watering hole and town square for a growing avant-garde. First made popular by a band of German intellectuals who became known as the “domiers,” including Wilhelm Uhde, Richard Goetz, and Alfred Flechtheim, these cafés—the Dome, the Coupole, the Rotonde, and the Select—served the same innovative function that the Cedar Tavern did for New York’s Abstract Expressionists. They provided especially efficient venues for spillover.

“It was extremely strategic . . . a military placing of avant-garde,” notes the art historian Romy Golan in Paris: The Luminous Years. “Those cafés become the place where artists meet. They are sitting in the cafés, drawing in the cafés on these wide sidewalks, and that is unique to Paris.”

Since the artists of Montparnasse often lacked toilet and kitchen facilities in their studios, they had little choice but to rub shoulders with one another in the cafés. “In the large cafés, small bistros, cheap restaurants, and art academies of Montparnasse,” said Apollinaire, the modern artists of Paris found “a substitute for the steeper slopes of Montmartre.”

The studio hub of Montparnasse served a similar function. Here a building known as La Ruche—literally, “the beehive”—provided eighty studios and two hundred beds arranged in the round. The main rotunda had been the wine pavilion at the 1900 Exposition Universelle, beside Eiffel’s new tower. A sculptor of funerary monuments relocated the building to Montparnasse in 1902.

Here the most striking variety of different nationalities came under one roof. Austrians, Russians, Scandinavians, and Americans all followed the Germans to Montparnasse. “There was a vast migration of Eastern European artists,” says Silver, “and it coincided precisely with the moment when things shifted from Montmartre to Montparnasse.”

Indeed, the residents of La Ruche were mostly Eastern European: Marc Chagall, Soutine, Jacques Lipchitz, Alexander Archipenko, Ossip Zadkine, or from Italy: Amedeo Modigliani and Ardengo Soffici. Soffici describes the international scene of the studio house as comprising “Frenchmen, Scandinavians, Russians, Englishmen, Americans, German sculptors and musicians, Italian modelers, engravers, fakers of Gothic sculpture, assorted adventurers from the Balkans, South America and the Middle East.”

Chagall similarly remembered his own stay at La Ruche: “While in the Russian ateliers an offended model sobbed, from the Italians’ came the sound of songs and the twanging of a guitar, and from the Jews debates and arguments. I sat alone in my studio before my kerosene lamp. . . . Down below and a little way off, they are slaughtering cattle. The cows low and I paint them.”

“I think of 1910 as the moment when Montmartre is finished,” says Silver of the rise of Montparnasse. “Modigliani arrived 1909. Picasso in 1912. The scene shifts towards the international, and Picasso was the perfect symbol of that, because he is not French.”

Montparnasse hosted an avant-garde collective that was dominated by foreigners. The sport of American boxing took the place of the circus and cabaret in captivating the interest of the avant-garde. Even the collector and writer Gertrude Stein, another resident, attended the matches, while the eccentric Cocteau liked to splash in the athletes’ leftover bathwater. As foreign style replaced bohemian influences, Picasso went on to design stage sets for the Ballets Russes and the exiled impresario Serge Diaghilev.

For Picasso, the rewards of knowledge spillover were more than artistic. A Paris auction of 1914, on the eve of the First World War, demonstrated it could be profitable as well. A decade before, a group of investors called the Peau de l’Ours pooled their money and began purchasing Modernist work. As planned, they then unloaded their purchases at a high-profile sale at the Hôtel Drouot, a major Paris auction house. Of all of their investments, Picasso’s work showed the greatest returns: His Family of Saltimbanquespurchased in 1909 for 1,000 francs, sold in 1914 for 12,650 francs. Spanish and American papers picked up on the sale, adding to Picasso’s growing fame. The artist made 4,000 francs from the auction for himself. From the ideas in the air of Paris, Picasso out-innovated everyone during his first decade in residence, enriching the art of the twentieth century along with himself. (As a Spanish national, unlike many of his fellow artists, Picasso continued to thrive through both world wars by pledging his loyalties to his own artistic production.)

The swift evolution of the Parisian avant-garde at the turn of the century, embodied in the innovations of Picasso, was not the linear progression of painterly style but the result of a knowledge spillover from an array of artistic, historical, and nationalistic influences.

It owed less to French style and everything to French democracy and its civic life, where personal liberties could be enjoyed in open cafés. In fact, by the start of World War I, French taste turned against the Modernists, who came to be viewed as unpatriotic and foreign—and by and large they were. Paris provided the framework for a band of innovators to develop their products by sharing their ideas in its restaurants, boulevards, and studios, but the School of Paris was underwritten by foreign enrollment. The nationalism of the First World War and the Nazi occupation of the Second finally put an end to Paris’s diverse artistic scene and the artistic innovations that spilled out of it.