Here’s a scary thought on the eve of the Civil War sesquicentennial: In the 1860 election, Abraham Lincoln was utterly beatable.

He won only 39.8 percent of the popular vote—the second lowest among all U.S. presidents from 1824 to the present day.

Had the Democratic Party not split before the election and been able to put forward a more effective and united ticket, Lincoln might not have won in the Electoral College. Had Lincoln not won, the South might not have seceded. Had there been no secession, would there have been a civil war? How would slavery have ended?

But history, as Meredith Hindley says, is the study of what did happen. And what did happen in 1860 was the Democratic Party split between Northern and Southern factions. They held competing nominating conventions that resulted in two separate tickets. At the head of one was Lincoln’s great nemesis, Stephen A. Douglas At the head of the other was the man who came in second in electoral votes: John C. Breckinridge.

But who was the guy who came in second? And how did the Democrats split? See Meredith Hindley’s illuminating profile of the talented young Breckinridge, the youngest person to serve as vice president.

Pauline Maier goes even further back in American history to review the losing side of another important contest: the fraught scrimmaging over drafts of the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787. The most eloquent and influential dissenter was George Mason, a cantankerous Virginian who said appreciatively about the brilliant men he met at the convention, “America has certainly, on this occasion, drawn forth her first Characters.”

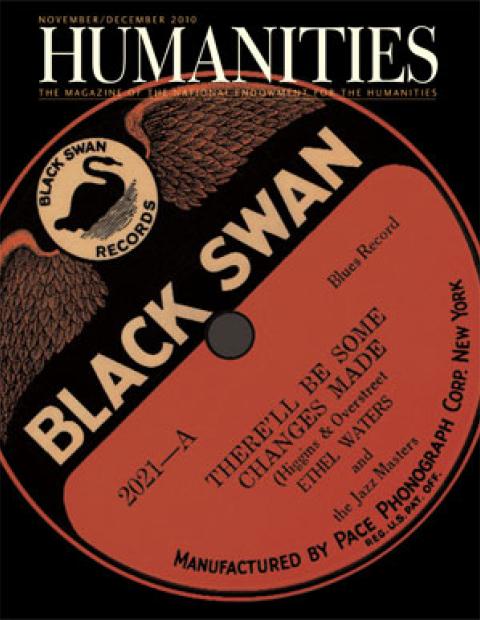

Harry Pace knew what it meant to be on the losing side of history. The African-American songwriter/businessman founded Black Swan Records to feature great jazz and blues artists like Fletcher Henderson and Ethel Waters. He also wanted to show that black artists could produce serious opera and classical music. His success and failure bring to mind the conflict that today gives us the term “booshie,” that prickly bit of African-American slang for the upwardly striving bourgeoisie.

Two decades before Pace set up shop in Harlem, Picasso was in Montmartre, similarly ensconced in a place and a moment of extraordinary artistic productivity. James Panero, on the occasion of a new NEH-funded documentary, asks, What was so special about this Parisian neighborhood? For an answer, he looks beyond art history to a concept of economics that appears in the writings of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs.

The girls of the Fort Shaw Indian School were no losers. In the early days of “baket ball,” they played all the way to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, crushing opponents as America celebrated westward expansion and the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase—achievements that had, of course, come at the expense of Native Americans.

Also in this issue of HUMANITIES: tales of intrepid curators searching the globe for lost Buddhist sculptures, a look at Edward Gorey aficionados, notes on the classical vocabulary of comic-book art, and much more.