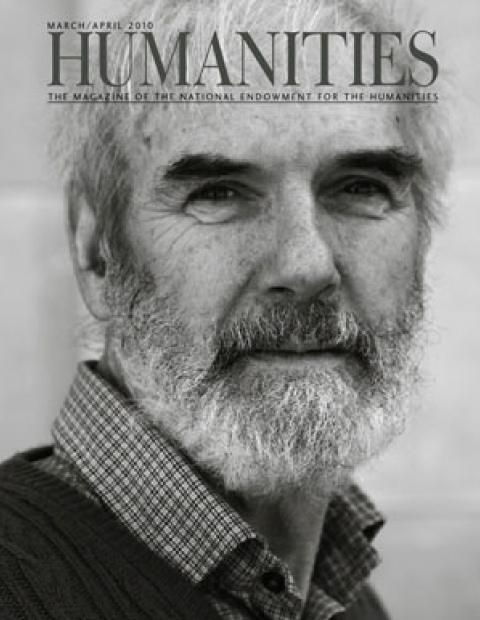

Where some might see a tourist attraction or vacation spot, Jamil Zainaldin sees sacred ground. “Red Top Mountain, the Sea Islands, Warm Springs,” he says. “Georgia is just filled with these places.”

Born in Virginia, Zainaldin, whose father was in the Air Force, attended high school in Georgia. In 1974, he reclaimed his grandfather’s ancestral name, which had been changed when his grandfather immigrated to the United States from Lebanon in 1910. For most of his professional life, Zainaldin was located in Washington, D.C., where he presided over the Federation of State Humanities Councils. In 1997, he took the helm of the Georgia Humanities Council.

“I know, most people do it the other way around—go from the state to the national level. But that was a good time in Georgia, it was having a financial growth spurt and was open to change,” he says. “And I am passionate about the humanities as a change agent.”

Ensconced in an Atlanta library where he is doing research this weekday afternoon, Zainaldin leans forward, eyes lively, eager to share stories he has gathered about the state’s historic significance.

Warm Springs, he says, had a huge impact on Franklin Delano Roosevelt and decisions he made for the nation before and during World War II. The Little White House is not just where FDR went to relax and swim in the mineral springs, but where he connected to the rural South and conceived of several New Deal programs. “The poverty, the nobility of the people . . . He was born a patrician, and it was polio and Warm Springs that changed him,” Zainaldin says. “That pool and its waters should be a shrine.”

Zainaldin, you might say, has an encyclopedic knowledge of the state. Under his tenure, the council has created the web-based New Georgia Encyclopedia (NGE), which Library Journal called the Best Reference Source on the Web in 2004. It boasts more than two thousand articles and five thousand photos. It has a video of Hank Aaron’s seven-hundred-fifteenth homerun at Atlanta-Fulton County stadium and audio of Ray Charles singing “I Got a Woman.”

An ongoing collaborative effort with the University of Georgia Press and the University System of Georgia/GALILEO, the encyclopedia has received support from governors Zell Miller, Roy Barnes, and Sonny Perdue. Edited by a small, devoted team, the website receives 1.2 million page views a month.

The council was recently approached by Wikipedia administrators about using NGE material with full attribution—contrary to Wikipedia’s usual practice. “We’ve given Wiki a dozen trial articles that will replace or be inserted into existing articles. We’ll hold the copyright and each article will have a hot link to the New Georgia Encyclopedia.”

Zainaldin holds a bachelor’s in history from the University of Virginia and a doctorate in history from the University of Chicago, and has authored several books on American legal history. He has taught at Northwestern University and Case Western Reserve University, and has been a visiting professor at Emory University in Atlanta.

The council has a budget of about $1.3 million a year, which, he points out, averages out to about thirteen cents for every man, woman, and child in Georgia. “There is a lot of opportunity, and a lot of need,” he says, pointing out that the state is still the lowest in high school graduation rates and forty-ninth out of fifty in public expenditures per capita. Still, he says, “this is a state that wants to move forward.”

Zainaldin makes his home in the leafy enclave of Dunwoody with his wife, Ingrid, and their two sons. He works in Atlanta, which is rich in cultural and educational resources, but he has ensured that the council reaches out to rural counties—Tifton, Dahlonega, Burke—with traveling museum programs like “Key Ingredients: America by Food,” library-based family reading programs, and competitions for local schools that teach students about civic responsibility and public policy.

There’s a lot of territory to cover—Georgia is the largest state east of the Mississippi—but also a lot of material to work with. Says Zainaldin, “The very ground we are walking on has secrets hidden from public view. If we really believe it’s important to live an authentic life, we must be aware that someone stood on this ground before us. We must preserve the Georgia stories that are in danger of disappearing.”