I become uneasy whenever someone mentions the “lessons of history.” Not that history doesn’t offer lessons, it’s just that many of the lessons, I find, are hardly the kind of rules for living that can be easily applied.

For instance, while reading The Death of Woman Wang by Jonathan Spence, I thought, now here’s a lesson: Do not become a seventeenth-century rural Chinese peasant. But I don’t think it will actually come up.

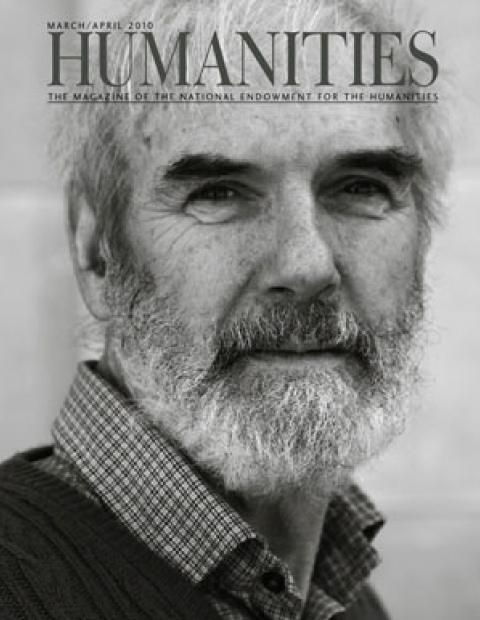

Spence is this year’s Jefferson Lecturer and his great writing takes you into some very dark and far corners of Chinese history. He is the author of many books, including The Search for Modern China, the standard textbook in Chinese history courses.

The Death of Woman Wang is a beautifully crafted, darkly riveting history of T’an-ch’eng County around the time of the Manchu invasion. One passage relates to the mass executions and mass graves of 1661 in Tzu-ch’uan, from a near contemporary account of artisans “making modest fortunes out of coffin building until the better qualities of wood ran out,” of gentry who “turned to lead bandit gangs in self-defense,” of robbers “who claimed they only killed ’unrighteous men,’” of “a destitute married couple carefully discussing whether he should become a bandit or the woman a prostitute.”

Spence’s intensely prosaic chronicle is also a lesson in how historical records can speak clearly across centuries and cultures. Simple facts, in the hands of a master writer, can be more eloquent than any literary device. And while such facts may not be practical in the narrow sense, it is broadening to the mind and spirit to confront the humble conditions from which humanity has been yanked into the bright light and comfortable circumstances of the present day.

Molière lived a much more comfortable life half a world away from Woman Wang; it was his afterlife that was crazy. As Steve Moyer relates in his essay “Burying Molière,” the great playwright’s remains were dug up and trotted around Paris during the French Revolution as a provocative history lesson of the new regime on the perfidy of the old.

By comparison, the lessons of philosophy may seem downright pragmatic. This issue tunes into “Why?,” a North Dakota public radio program devoted to the unexpected proposition that philosophy is for everyone. Grand Forks correspondent Paulette Tobin interviewed the show’s host, Jack Russell Weinstein, to learn what possessed him to do “Philosophy on the Radio.”

Last, we have a postcard from Saipan, one of the Northern Mariana Islands, where the novelist P. F. Kluge gave a series of lectures on classic works of American literature. A guest of the local humanities council, Kluge recalls the island as he knew it as a Peace Corps volunteer in the sixties and takes notes on what it’s like today, all the while plying his trade as an evangelist for the written word. Kluge finds a lot of history, and even some lessons, in this farthest outpost of America.