“What do ye do when ye see a whale, men?”

“Sing out for him!” was the impulsive rejoinder from a score of clubbed voices.

“Good!” cried Ahab, with a wild approval in his tones; observing the hearty animation into which his unexpected question had so magnetically thrown them.

“And what do ye next, men?”

“Lower away, and after him!”

“And what tune is it ye pull to, men?”

“A dead whale or a stove boat!”

The call-and-response of Ahab’s maniacal pep rally—a string of, as Ishmael puts it, “seemingly purposeless questions” with which the Pequod’s captain stirs his crew into a bloodthirsty furor for whale-killing—culminates in what one scholar of American folklore has called the “universal motto” of nineteenth-century whalemen: “A dead whale or a stove boat!” Like a seagoing version of the Depression-era bumper slogan “California or bust,” the phrase pithily evokes both the mariners’ desperate dedication to the pursuit and destruction of their prey and the extreme risks they incurred in the process. “A dead whale” was, of course, the desired outcome of the chase, but “a stove boat”—a wrecked mess of splintered timber, fouled tackle, and flailing bodies—was just as likely. For the fictional crew of the Pequod, as for the real whalemen of the day, whaling was more mortal combat than straightforward hunt: Six sailors in a flimsy, open whaleboat, armed with only handheld harpoons and lances, pitting themselves at every opportunity against the singular terror of a true sea monster, the sperm whale, an animal that, when fully grown, could measure sixty-two feet in length, weigh eighty tons, and wield, to deadly purpose, a eighteen-foot jaw studded with seven-inch teeth.

Into the Deep: America, Whaling & the World, a new American Experience documentary by Ric Burns, is alive with the all-or-nothing ethos of the nineteenth-century whaleman. Drawing its central narrative arc from two of the most famous man-versus-whale tales of the era—the true, though at the time unthinkable, story of the Essex, a whaleship sunk in the middle of the Pacific by an enraged sperm whale, and the dark masterpiece it partially inspired, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick—the film follows the history of the American trade as it evolved from the colonial practice of “drift whaling” through the so-called Golden Age, which lasted from shortly after the War of 1812 until the commercialization of petroleum after it was successfully drilled in 1859. During that time, Nantucket, New Bedford, and other port towns sent hundreds of ships all over the globe in search of leviathans. This was before modern whaling technologies reduced the drama and heroics of the chase to mere assembly-line slaughter, when whaling still represented, in the words of several scholars interviewed in the film, a “primordial . . . epic hunt, . . . tap[ping] into something very basic about human existence and experience,” “a spiritual endeavor,” and a “peculiar combination of romance, . . . danger, and exoticism.” Those brave enough to ship out on a Yankee whaler could expect to hunt the biggest game, explore new corners of the ocean and faraway lands, dally with foreign women, and hack to pieces and boil down behemoth carcasses.

Wait. Hack and boil carcasses?

For all the antiquarian nostalgia that risks tinting our view of the fishery’s past, Into the Deep never loses sight of the simple fact that whaling was an industry—one of the largest, most profitable, and important businesses of its day, involving tens of thousands of workers at sea and on shore, and millions of dollars in annual investments and returns. It is a refreshingly clear perspective for those of us who may have thumbed quickly past the more technical chapters of Moby-Dick, or who imagine whaling through the narrow lens of those impressive painted and scrimshawed scenes of vicious whales smashing boats and tossing sailors in the air. Men went to sea for any number of reasons—to make a living, to escape the law, to find themselves—but once aboard a whaleship, their job was to supply the rapidly industrializing Western world with oil for its lamps, candles, and machinery, and baleen for its parasol ribs, horsewhips, and corsets. And as author Nathaniel Philbrick, one of the experts appearing in the film, said in a phone interview: “It’s not as though the harpoon hit the whale and—poof—magically it was turned into a profitable commodity.” To effect that transformation required some of the most difficult and disgusting labor of any industry of the time.

“We have to work like horses and live like pigs,” wrote Robert Weir, a greenhand (or first-time sailor), in his diary. His experiences aboard the whaleship Clara Bell from 1855 to 1858 correspond to many scenes from Into the Deep. After only forty-eight hours at sea, his “eyes,” he said, were already “beginning to open” to the harsh realities of his “rather dearly bought independence.” He had shipped out to cut ties with those on land—his family and creditors—but to what end? The life of a whaleman was not, it turned out, all battling leviathans, exploring exotic isles, and cavorting with natives. In fact, for the most part, it was downright miserable. The quarters were cramped, the food was awful, and the work, when there was any to be done, positively backbreaking. After one especially long day, Weir jotted in his diary, it “rained pretty hard in the evening—and I got wet and tired tending the rigging and sails. Tumbled into my bunk with exhausted body and blistered hands.” To this account he appended a one-word commentary, as bitterly sarcastic as it was short: “Romantic.”

Although wooden whalers required, as Weir put it, “innumerable jobs” just to keep afloat and moving forward, the really hard work of whaling didn’t begin until after the brief thrills of the chase were brought to a successful conclusion. If a whaleboat crew were skilled and lucky enough to kill a whale—to make it spout blood and roll “fin out,” in the colorful language of the fishery—the men would then have to tow the carcass to the waiting mother ship, which could be anywhere from a few yards to several miles distant. As Mary K. Bercaw Edwards, a professor of maritime literature at Williams College–Mystic Seaport Program, points out in the film, dragging tens of tons of deadweight through the water under oar was anything but easy: Six men working themselves raw could only achieve a top speed of one mile per hour. Even a mariner seasoned by years in the merchant service described towing a dead whale as “one of the most tedious and straining undertakings I have ever assisted at.”

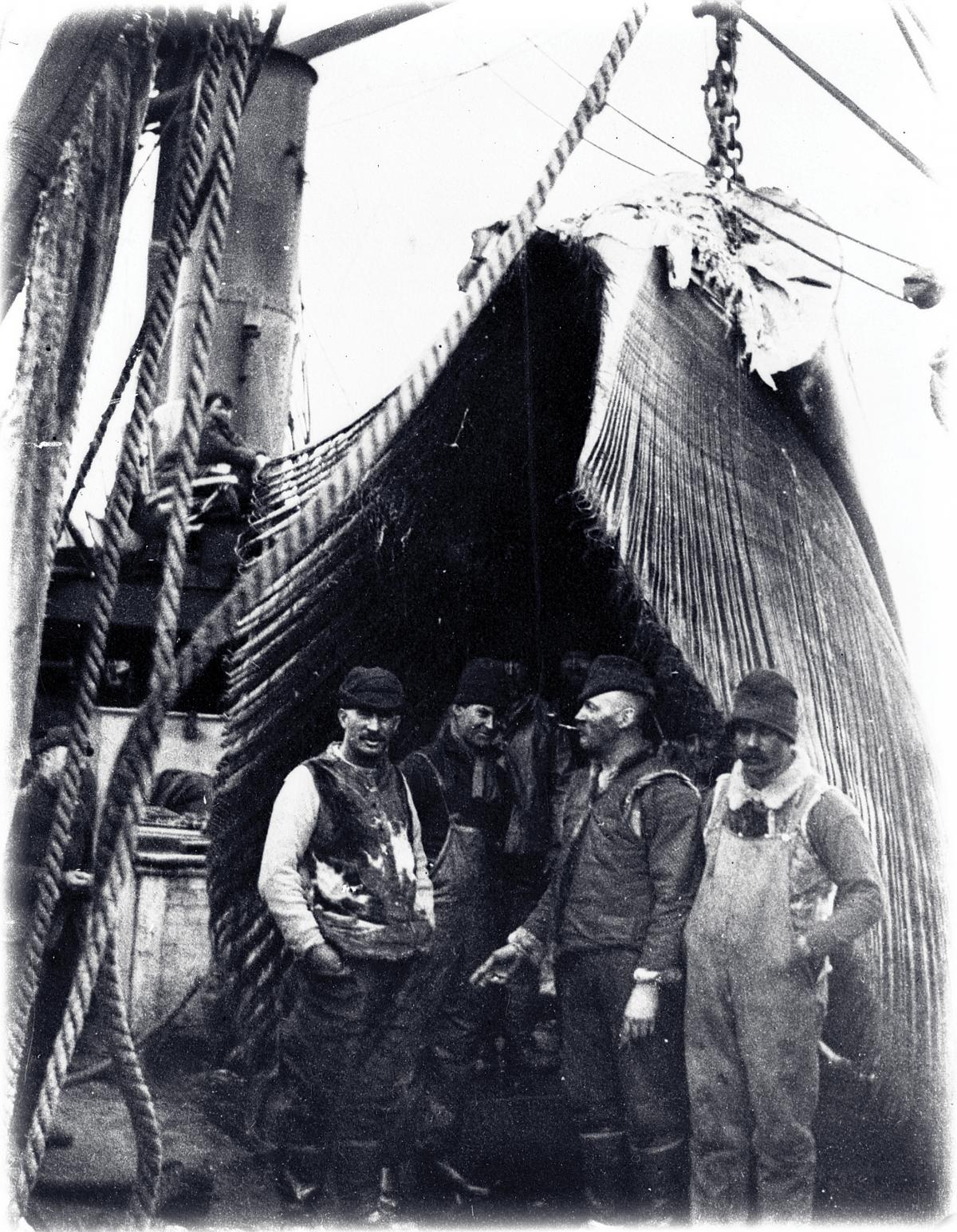

And, as some of the archival photographs and footage Burns dredged up for Into the Deep graphically attest, things didn’t get any easier after the whaleboat met the ship. Brought alongside, the corpse was secured to the starboard side of the vessel, whale’s head to ship’s stern, by a large chain about its flukes and sometimes a wooden beam run through a hole cut into its head. Soon, all hands—except, in American whalers, the captain—were given over to the bloody task of “cutting-in,” by which the whale was literally peeled of its blubber—“as an orange is sometimes stripped by spiralizing it” is the simile Melville and other salts and scholars have used to illuminate the process. With a few deft slashes of a fifteen-foot cutting spade, an experienced mate would loosen a portion of flesh and blubber between the animal’s eye and fin, while another man, braving the sharks that were by now swarming the grisly mass, boarded the body, and fixed a huge hook to the cut swath of whale. Drawn up into the rigging, this hook began ripping a long strip of blubber, called a “blanket-piece,” from the carcass. Measuring some five feet wide, fifteen feet long, and ten to twenty inches thick, blanket-pieces were borne aloft and aboard, where they could be cut down to sizes suitable for “trying-out,” the next step.

Gruesome as cutting-in may seem to most of us, unaccustomed as we are to the scenes that unfold daily in slaughterhouses and aboard commercial fishing vessels, it was really nothing more than whale-scale butchery—certainly not the kind of thing any hunter, especially one who had just gone through all the trouble and gore of killing a whale, would cringe at. But trying-out, the process of boiling oil from the stripped blubber, was another story. Working around the clock in six-hour shifts for one to three days (depending on the size of the whale killed), the crew kept the two giant copper cauldrons of the try-works burning, tossing in hunks of blubber and barreling the gallons and gallons of oil they rendered. Almost every whaling memoir contains some stomach-turning account of this process. Melville’s highly poetic version is quoted in the film, but Charles Nordhoff’s 1856 Whaling and Fishing, with which the author aimed, he said, “to give a plain common sense picture of that about which a false romance throws many charms,” offers one of the most visceral litanies of the distasteful conditions trying-out created aboard ship. “Everything,” the seaman wrote, “is drenched with oil. Shirts and trowsers are dripping with the loathsome stuff. The pores of the skin seem to be filled with it. Feet, hands and hair, all are full. The biscuit you eat glistens with oil, and tastes as though just out of the blubber room. The knife with which you cut your meat leaves upon the morsel, which nearly chokes you as you reluctantly swallow it, plain traces of the abominable blubber. Every few minutes it becomes necessary to work at something on the lee side of the vessel, and while there you are compelled to breath in the fetid smoke of the scrap fires, until you feel as though filth had struck into your blood, and suffused every vein in your body. From this smell and taste of blubber, raw, boiling and burning, there is no relief or place of refuge.”

And there was more. To quote Melville: “It should not have been omitted that previous to completely stripping the body of the leviathan, he was beheaded.” As the blanket-pieces were rent from the dead whale, its body turned in the water, straining against the fixed head, until, with some more plying of a spade, the two portions were wrenched apart. If the head was of a manageable size, it was brought on deck; if not, it was rigged to the side of the ship, nose down. Right, bowhead, and fin whales were relieved of their baleen, while sperm whales had the spermaceti, a substance contained in a head organ known as the case, bailed out in bucketfuls. “This is the good stuff,” says Philbrick in the film. “It’s as clear as vodka when you first open” the spermaceti organ, “but as soon as it touches air, it begins to oxidize,” taking on the white, waxy properties that caused early whalemen to mistake it for the animal’s semen. Scientists still don’t know what function spermaceti serves in whale physiology, but for the men and women of the nineteenth century, it was simply the best illuminant and lubricant money could buy. In fact, the light given off by candles manufactured with spermaceti was considered so superior to that of other types of candles that it served as the benchmark for all artificial light: One candlepower, as defined by the English Metropolitan Gas Act of 1860, was equivalent to the light of a pure spermaceti candle of one-sixth pound burning at a rate of one hundred and twenty grains per hour. The spermaceti-based unit survived until an international committee of standards agencies redefined the measure in 1909 to conform with the luminous properties of the then recently invented electric carbon filament bulb.

Finally, with all the blubber processed, all the spermaceti bailed, and the decapitated corpse left for the sharks and scavenging birds, the crew set about giving the ship a thorough scouring. This was accomplished with a combination of strong alkali and sand, or sometimes an effective concoction of human urine and whale blubber ash. Only when the ship was returned to its pre-processing shine—“with a sort of smug holiday look about her,” wrote one sailor—did the men even attempt to clean themselves. “Happy day it was for me,” remarked Nordhoff, “when I was once more permitted to put on clean clothes, and could eat biscuit without oil, and meat unaccompanied by the taste of blubber.” A well-earned respite to be sure, but, of course, only temporary: The entire laborious, nauseating operation, from chasing down to trying-out to cleaning up, would be repeated perhaps as many as one hundred and fifty times until, if the cruise was a “greasy” one—the whalemen’s esoteric but wholly appropriate word for “good,” “fortunate,” or “lucky”—the hold practically overflowed with whale oil, spermaceti, and baleen. A prospect that, one imagines, might have caused more than a few greenhands to hesitate for a moment before yelling, “There she blows!” at their next glimpse of a whale.

And yet, for all the hardships involved, men shipped with Yankee whalers in droves throughout the Golden Age. The experience of whaling was, it seems, something irreducible to the sum of its working parts. “At the end of the day,” Burns says, whaling in the nineteenth century was still “an extraordinarily primal, existential confrontation between human beings and what was really the last frontier of untamed nature, the oceans of the world.”

Indeed, Melville, Weir, Nordhoff, and countless other whalemen of the time didn’t just “work like horses and live like pigs”; they had adventures, too. They took on and dispatched the largest animals on the planet, lived as captives among cannibals, saw islands no one had ever seen before, plumbed the depths of their souls and psyches while scanning the ocean from the masthead.

“At some point,” Burns says, “one wants to see whaling for what it was and understand the crucial admixture of cruelty, and greed, and nobility, and courage, and generosity, and selfishness, and withal the magnificence of the enterprise, even as one says, ‘Thank God it’s gone. Thank God we’re not out there on three-hundred-ton ships prowling the world, looking for mammals to turn into umbrella stays, lamp oil, and lubricant.’”