The natural and the supernatural, the mental and the moral, verse and adversity all make an appearance in this issue of HUMANITIES. As the ancient playwright Terence put it, “I am human, I consider nothing human to be alien to me.”

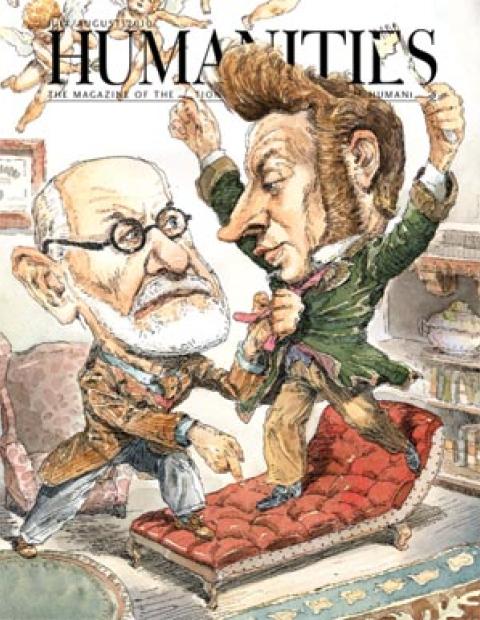

And religion is human, all too human according to some. Sigmund Freud called it an illusion, and that was one of his gentler comments. But if he had been a believer, his ideas might have sounded more like Soren Kierkegaard’s. As Gordon Marino shows, Freud and the Danish father of existentialism had much in common. Both were psychologists—more or less.

John Mitchell Jr. did not claim to be a psychologist. The crusading newspaper publisher took on the lynchers in Reconstruction-era Richmond. And yet he did claim to know the minds of the city’s black citizens: “Do you want to know what Colored People think? Read the Planet,” he wrote. “Do you want to know how many Colored People are hung to trees without due process of law? Read the Planet. Do you want to know how Colored People are progressing? Read the Planet.”

Reading about his incredible courage in Donna Lucey’s profile, my mind kept returning to a later injustice: Why isn’t this guy famous? Why isn’t there a big Hollywood movie about him? The story’s got everything: a righteous angle, riveting history, and the beautiful thumping voice of a great individual.

The way things are going for Emily Dickinson’s reputation, one would not be surprised to see her on the big screen, writing love letters perhaps, but also gardening. Her neighbors never had a chance to read her poetry while she was alive, but they did get an eyeful of her hydrangeas. Inspired by a recent exhibit dedicated to Dickinson’s horticulture, garden writer Tom Christopher looks at the border separating the lyrical from the lilacs.

There was more Poe than poetry in the tale of Dr. George Parkman’s disappearance. The story of this well-known murder at Harvard University is newly rendered in an NEH-supported walking tour using personal digital technology. Cambridge writer Craig Lambert follows the deadly trail.

The means of death were a little more mysterious, but also Gothic, in the novel Wieland. Then again, much was mysterious, Anne Trubek finds, in the life and fiction of the first American novelist, Charles Brockden Brown.

This issue also boasts a contribution from John Patrick Shanley, the writer of Doubt and Moonstruck. Laura Wolff Scanlan brought it back from New Orleans, where she was scouting out the Tennessee Williams Festival. Like Terrence, Williams had a great hungry interest in all that man might do or say, a passion he squeezed into two little words: “Stell uhhh!”