“I had naturally a knack for contriving.”

In 1830, Peter Cooper designed, built, and drove the first steam-powered locomotive to operate a public railroad in the United States—a feat of engineering that helped ensure the future success of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. In 1845, he patented a “condensed” gelatin food product that later became the ubiquitous Jell-O brand fruit dessert. In 1852, he challenged workers at his Trenton Iron Company to come up with a new kind of structural beam that could be used in large-scale construction projects. Beams produced at his ironworks soon found their way into the Assay Offices in New York, the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia, and the Capitol dome in Washington, D.C. And in 1858, as an honorary director of the Atlantic Telegraph Company, he was instrumental to the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph line.

Even this drastically abbreviated list suggests a far more penetrating faculty than a mere “knack for contriving.” Born in 1791 to a poor family in New York City, Cooper, by dint of his unflagging industry, intellect, and, he would have said, faith, made a fortune as a glue-maker. He then went on to become one of the important shapers of what might be called American modernity. He touched, and in some cases radically transformed, so many facets of the contemporary milieu—travel, monetary policy, communications, architecture—that it would seem all but impossible to pin down his single greatest contribution to the era. But when in 1882, at the age of ninety-one, Cooper sat down with a stenographer to dictate his autobiography, it was the small school he had founded in his hometown that seemed to him his greatest achievement.

“In reviewing the whole course of my life,” he said, “the money that I expended in building the institute . . . I look back upon as one of the best treasures that I have been able to lay up for old age, and which I hope to reflect on with pleasure when I pass into a brighter and better world.”

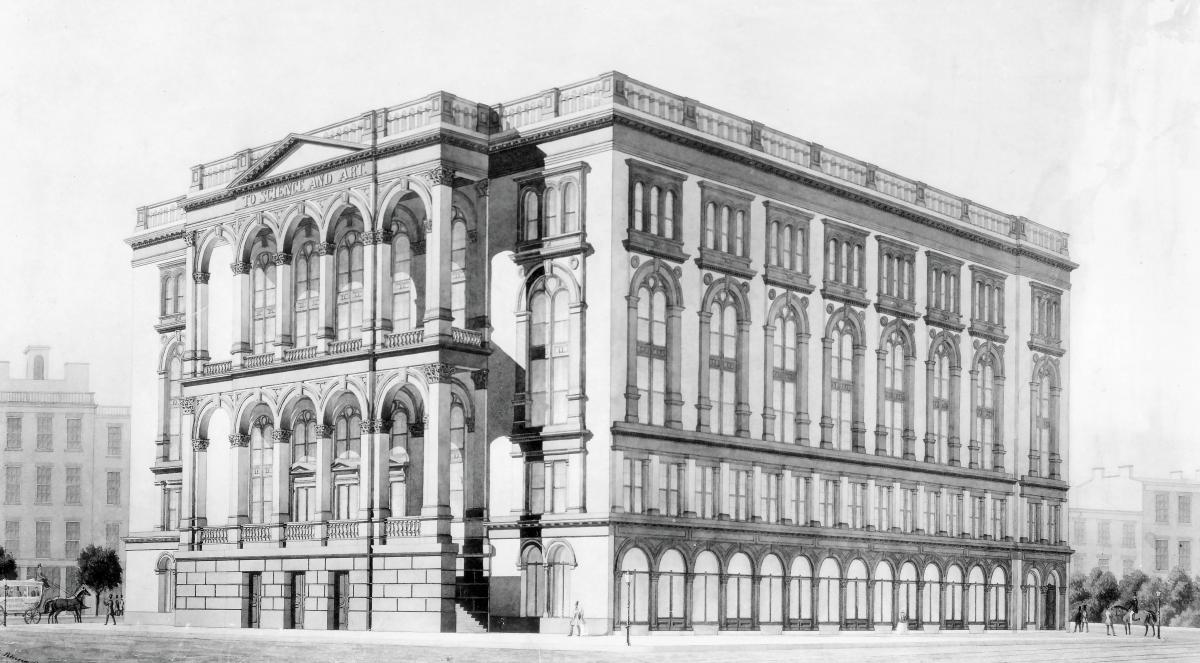

When the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art first opened its doors in 1859, it represented for Cooper the realization and commencement of an idea that had occupied—perhaps even preoccupied—his imagination for nearly thirty years. In the early 1830s, he had listened with interest to a friend, one Dr. Rogers, recount his recent experiences at the École Polytechnique in Paris. Of everything Rogers told him—about the school’s professors, curriculum, and scientific apparatus—Cooper was most impressed by the character of the students, who, he was told, pursued their coursework admirably despite subsisting on nothing but “a bare crust of bread a day.” The story of these young men (the École did not admit women until 1972), impoverished, hungry, and yet wholly dedicated to their studies, touched a chord with Cooper: His own formal education had consisted of only “some three or four quarters” at a public school during his childhood, and though he had wanted to pursue scientific training in later life, he found that “there were no night schools or laboratories nor any means by which an apprentice boy could get information.”

Cooper became convinced that there were any number of would-be engineers, architects, artists, and inventors among the working classes of New York who, if given the chance, “would gladly turn away from vitiating pursuits to enjoy the beauties and benefits of a course of scientific instruction.”

“I formed a very resolute determination,” Cooper later said, “that if I could ever get the means, I would build an institution and throw its doors open at night so that the boys and girls of this city, who had had no better opportunity than I had to enjoy means of information, would be enabled to improve and better their condition, fitting them for all the various and useful purposes of life.”

But here, of course, philanthropic impulses outstripped practical experience. Having never received a full course of academic instruction himself, Cooper had little idea how best to go about educating others. He drew inspiration from a wide variety of institutions, educational and otherwise: the French École, the Girard College in Philadelphia, the University of Pennsylvania, and even P. T. Barnum’s American Museum of curiosities in New York.

“He was a bit of a magpie,” says Peter Buckley, the unofficial institutional historian at Cooper Union. “There wasn’t an educational idea he came across that he didn’t think was good.” Along with more familiar collegiate facilities—a grand lecture hall, a public reading room, and a museum—Cooper envisioned a cosmorama (a popular type of peepshow that displayed oil paintings of foreign landmarks and exotic vistas through convex lenses intended to enhance their realism), a series of small lounges in which students could congregate to debate their ideas, and a recreational rooftop tea garden, complete with ice-cream parlor and bandstand.

Fortunately, Cooper’s advisers—chief among them, his Columbia-educated son-in-law, Abram S. Hewitt—had other plans for the Union. “Learning by looking,” as Buckley succinctly describes Cooper’s loosely conceived educational philosophy, was simply outmoded: The new industrial age demanded a systematic approach to scientific training. If the school was to be an effective means of educating, and thereby elevating, the working classes of New York, it would have to forgo some of Cooper’s more peculiar notions in favor of intensive and structured sequences of courses.

Although Cooper, Hewitt, and the Union’s other trustees must have debated Cooper’s ideas, historians have found relatively little documentary evidence to suggest the course of those debates. Last October, however, the library at Cooper Union received a cache of Cooper-Hewitt family papers from the Passaic County Historical Society, “some of which,” says Union librarian Carol Salomon, “appear to be sketchy outlines of what the curriculum should be.” Scholars have not yet had a chance to review these documents thoroughly, but, whatever they ultimately find, it is clear that Hewitt’s plans won out in the end: The space Cooper had intended for the cosmorama was broken up into laboratories, the discussion lounges became classrooms, and the plan for a decorative rooftop garden was abandoned altogether.

By about 1861, Buckley believes that Hewitt was effectively running the school and that Cooper was settling into his new role as the Union’s paterfamilias. No longer involved in daily operations, curriculum design, or faculty management, Cooper became a supervisory father figure whose purpose—to represent the Union’s founding principles—was largely achieved by his simply being there. And Cooper was there: He could be found almost every day, for the twenty-two years remaining to him, in and around the school, enthusiastically leading tours of the building, inconspicuously dropping in on lectures, and sharing his thoughts, opinions, and favorite passages of poetry with the students.

It is hard to argue against the efficacy of Hewitt’s changes. For one hundred and fifty years the Union has successfully fulfilled Cooper’s broadest goal: providing a tuition-free education to men and women of all social, ethnic, and religious backgrounds. Still, one wonders what Cooper’s Union might have accomplished if it had been executed according to his original plans. Rossiter W. Raymond, a friend of Cooper’s and one of his earliest biographers, suggested in 1901 that the rooftop tea garden would not have been an extravagance, but a powerful symbolic reminder of the elevating potentials of a truly democratic system of education. According to Raymond, Cooper had conceived “an idea to which the slow thought of his fellows had not yet attained—the plan of utilizing roofs for the purpose of giving to all classes an ownership of free air and far distance and boundless sky as complete as any landowner could command.” Buckley offers a less poetic but, considering Cooper’s holistic educational goals, likelier explanation: “The tea garden would have been a gesture toward the idea of ‘rational recreation,’ as it was then called, a place that would encourage polite, democratic sociability.” Either interpretation seems adequate to justify a wistful remark Cooper made one day while standing on the unused roof of the Union, “Sometimes I think my first plan was the best!”

But there are, perhaps, some faint echoes of Cooper’s unrealized rooftop plans in the Union’s new academic building at 41 Cooper Square. An arresting work by Pritzker Architecture Prize-winner Thom Mayne, the building’s top has a “green roof” planted with environmentally friendly flora, a terrace for social gatherings and special events, and a conference room. The only aspect of Cooper’s initial plans missing from this modern space, it seems, is the ice-cream parlor.