The greatest American literary sensation of the post-Civil War decade had its origins in a conversation between Thomas Niles, an editor at the publishing house of Roberts Brothers, and Bronson Alcott, the father of a thirty-five-year-old writer whom his wife had named for a favorite sister, Louisa May. When the elder Alcott and Thomas Niles sat down to talk business in May 1868, Louisa May Alcott had a respectable, if still modest, reputation as a highly prolific and versatile author. Her work had appeared several times in the prestigious Atlantic Monthly. Her Hospital Sketches, a slightly fictionalized memoir of her work as a Union Army nurse, had been hailed as a work of “uncommon merit,” and her one published novel, Moods, had been reviewed, if somewhat coolly, by the young Henry James.

But as Louisa herself knew, she had not risen to her full artistic potential. Now her father, in an effort to drum up some work for her, suggested to Niles that Louisa could write him a book of fairy stories. Niles was not taken with the idea; what he really wanted was a book to fill a yawning gap in the juvenile market—a smart, lively novel for girls. He had approached Louisa herself with the same idea the previous autumn. She had told him she would try, and promptly started the project—and just as promptly set it aside. It was not simply that she disliked the idea, though that was true enough. Her experience also told her that writing for juveniles “doesn’t pay as well as rubbish.” Still worse, Alcott considered herself wholly unqualified for the task. An irrepressible tomboy in her youth, Louisa had “never liked girls or [known] many” other than her three siblings: her older sister, Anna, and her younger sisters, Lizzie and May. She saw only a faint possibility that the “queer plays and experiences” that the four of them had shared would interest a popular audience.

All of her concerns, however, were finally outweighed, as they often were, by Louisa’s desire to help her father. Bronson Alcott, whose capacity for fascinating conversation was so great that people paid to hear him talk, had repeatedly failed to convert his verbal inspirations into writing. Nevertheless, he was now revising a philosophical manuscript called “Tablets,” which was possibly the best work he had ever done. Niles, however, would take Bronson’s book only on one condition. He must have Louisa’s book for girls. That settled it.

Louisa flung herself into the project. She liked the idea of using the name of a month, like her own middle name, as a surname of the family of girls that she would closely base on herself and her sisters. Because she wanted a colder, harsher month, however, the Alcotts became not the Mays, but the Marches. Inspired by her own rough-and-tumble adolescence, she also fancied the idea of a tomboy main character whose given name could be shortened to sound like a boy’s; within her own family, she had been known as “Lu.” Thus Josephine or “Jo” March was born.

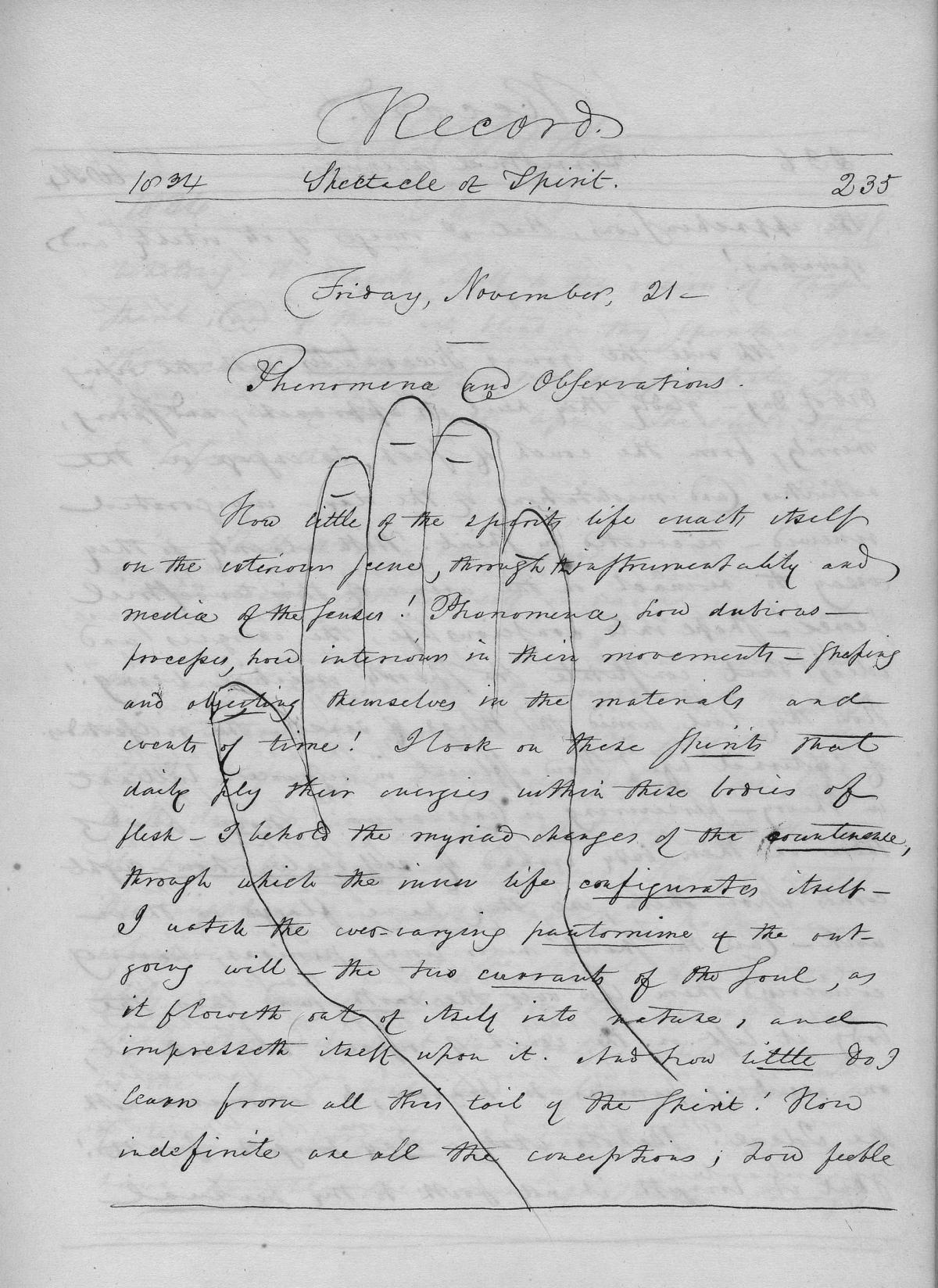

Writing at the small, semicircular desk that her father had built for her, barely taking time to eat or sleep, Louisa produced 402 manuscript pages in two months and then collapsed from fatigue. Her heart heavy, her head “full of pain from overwork,” Louisa still entertained few hopes for the thick packet she sent off to Niles under the title of “Little Women.”

For a woman who liked to observe that everything in her life went “by contraries,” the contrast between Alcott’s expectations regarding Little Women and its phenomenal success was only one in a series of improbable circumstances that influenced both her character and her art. These circumstances originated largely within her family, for there could have been no father more unusual than Bronson Alcott.

In an age when few fathers took primary responsibility for the care of their children, Bronson was so obsessed with the subject of parenthood that he kept exhaustive journals that recorded every event in the early growth and development of his three eldest daughters. Whereas Americans of previous generations tended to see nothing distinctive about the minds of children, Bronson regarded them with outright worship. “Look not into the world,” he wrote, “for the image of the Father. There it is dimmed, disfigured. But look into the radiant face of childhood ere earth hath left its traces upon it, and be blessed—nay, saved!”

Believing that children, so recently arrived from the celestial realm, possessed a purity that could redeem humankind, Alcott founded a series of schools dedicated to drawing out the divine essence of his pupils and a potent moral philosophy. Although his schools drew lavish praise from men like Ralph Waldo Emerson, who became a lifelong friend of the Alcott family, Bronson never felt that he could reach the children of other parents soon enough to perfect his theories. He therefore turned toward his own home, where he hoped to discover the secret of infant perfection in his own daughters and publish his findings to a respectful world.

Carefully controlling their environment to exclude all influences they deemed harmful, Bronson and his wife, Abigail, tried to give their children an ideal—if highly scrutinized—upbringing, exhorting them to resist every selfish impulse and to indulge every creative one. On the one hand, youngest daughter, May, was allowed to draw on the walls of her room. On the other, four-year-old Louisa was required to give up the last slice of her birthday cake when an unexpected guest arrived at the party.

The NEH-funded documentary Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women, to be aired December 28 on PBS, contains a charming scene that nicely encapsulates the atmosphere of the Alcott home. In the scene, Bronson lies with young Louisa on the floor of his study, using his uplifted legs to teach her the letter “V.” When Bronson could relate to his children in a context of learning, he did so with passion and pleasure. However, his parenting was dominated by theory and perfectionism, and he could deliver painful reproofs when his children did not rise to his lofty expectations.

These criticisms, it seems, fell disproportionately on Louisa. Impetuous, high-spirited, and cursed with a sometimes ferocious temper, she resisted her father’s efforts to shape her into a model child. Bronson’s theories could account neither for her violent mood swings nor for the fact that her favorite pastimes included falling out of trees and running away from home. Never guessing that Louisa’s volcanic nature might signify a greater brilliance than his paradigms accounted for, Bronson denounced Louisa in his journals, calling her “unfaithful” and even a “devil.” Louisa tried to parry his critiques with humor, signing early letters to him as “your loving demon.” But Bronson’s faultfinding had deep effects. It took decades before Louisa felt sure of his love in all aspects of life.

The Alcotts’ idealism reached its pinnacle in 1843, when Bronson and an English reformer, Charles Lane, cofounded a utopian community called Fruitlands, whose members swore off all animal products, as well as coffee, tea, and any commodity generated by slavery. The Fruitlands community called itself a “consociate family,” meaning that all its members were entitled to an equal claim on one another’s loyalties and affections. Ill-planned from the start, Fruitlands foundered in less than a year, but not before Bronson and Lane had proposed that the men imitate the Shakers by segregating themselves from the women. Since the only women left at Fruitlands by this time were Abigail and her daughters, the plan essentially meant that Bronson would leave his family. Eleven-year-old Louisa responded with tearful prayers. In her journal, she begged God to keep her family together. The Alcotts did not separate. However, Louisa’s experience of first gaining a larger family and then watching her biological family nearly dissolve left a tremendous impression. It both convinced her of the importance of family unity as a bulwark against misfortune and opened her mind to the possibility of forming close attachments on some basis other than blood or marriage. Both the centrality of the family and a willingness to redefine family on broadly inclusive terms were to characterize much of her later writing.

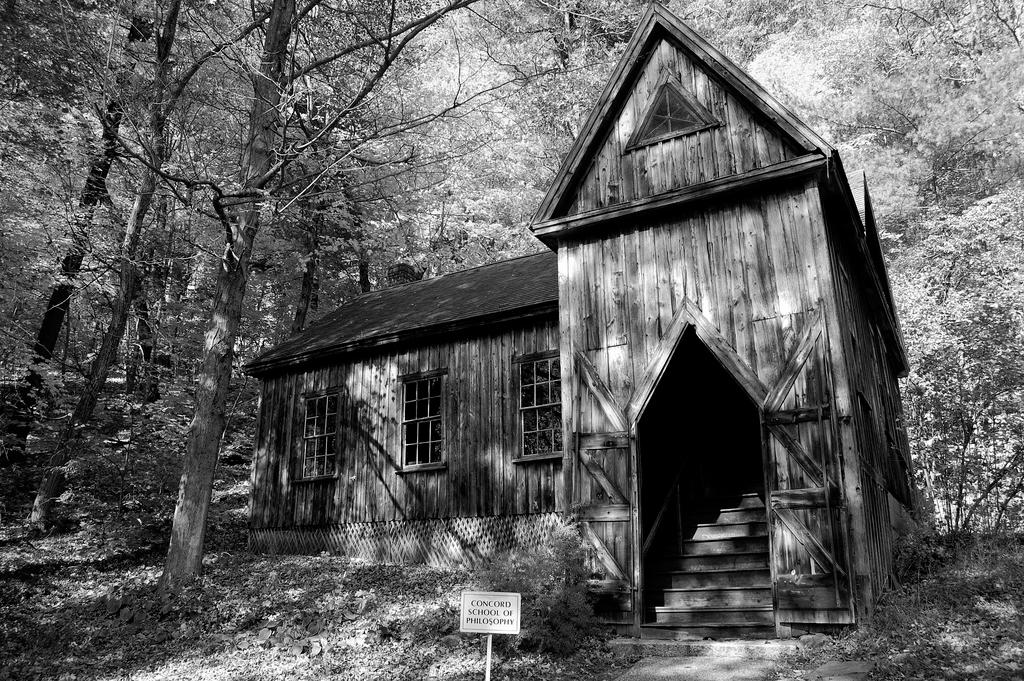

The signature dissonance of Louisa’s formative years was the contrast between its lush intellectual richness and its grinding material poverty. Alcott expert Joel Myerson has quipped that, during her family’s years in Concord, Massachusetts, Louisa May Alcott grew up inside the Norton Anthology of American Literature. Before Louisa reached the age of eight, she had attended school in a room in Emerson’s house. During her teenage years, Emerson gave her free access to his library, from which she borrowed such works as Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship. Under his watchful supervision, she discovered Milton, Schiller, and Carlyle. Emerson’s fellow transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau played his flute for her and took her on nature walks through the Concord woods. Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose novels and tales were regular fare in the Alcott household, took little evident interest in Louisa’s education. Nevertheless, he was a longtime family acquaintance and, for the last four years of his life, their next-door neighbor. This Concord constellation did much to open Louisa’s eyes to nature, literature, and life. Yet every day spent among Emerson’s books and Thoreau’s woods ended with a trudge back to a home where supper was likely to consist of coarse bread and apples, where the father was habitually out of work, and all were, as Louisa described somewhat later, as “poor as rats.”

The august tutelage of Emerson, Thoreau, and her own father made Louisa acutely conscious of the importance of unseen, spiritual realities. At the same time, however, her father’s asceticism, ironically intended to teach the Alcott girls the unimportance of worldly wealth, powerfully persuaded Louisa of the importance of money. By personal observation, she discovered that metaphysical essays and meditations on the Oversoul earned little. Unlike her great triumvirate of mentors, she had no desire to explore nonfiction. Because of her family’s chronic indebtedness, writing for her was always a matter of “tak[ing] Fate by the throat and shak[ing] a living out of her.” Indeed, her authorial ambitions were so distant from those of her transcendental mentors that, after she published her first successful book, Hospital Sketches, in 1863, she made the surprising claim that she “never had a literary friend to lend a helping hand.” Only once in her important fiction does Louisa engage directly with the philosophical movement that enthralled her father, and the story in which she does so, a fictionalization of the Fruitlands experiment called “Transcendental Wild Oats,” plays its subject primarily for laughs.

Literary influence can be terribly difficult to trace. In its sympathy for the plight of working women, its love of playful characterization, and its unerring aim at the most tender sentiments of its readers, Alcott’s fiction seems to owe less to her close acquaintances than to Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, and Harriet Beecher Stowe—authors with whom her personal connection was either slight or nonexistent. In her greatest book, Little Women, Alcott’s mother and sisters are all boldly transformed into enduring characters, whereas Mr. March, the novel’s patriarch who shares many traits with Bronson, is barely visible. Nonetheless, Emerson, Thoreau, and the elder Alcott can be found in Louisa’s fiction, if one knows where to look. Louisa began Moods, her first novel for adults, with an epigraph from Emerson’s essay “Experience”: “Life is a train of moods like a string of beads; and as we pass through them they prove to be many-colored lenses which paint the world their own hue, and each shows us only what lies in its own focus.” Emerson appears in Moods as Geoffrey Moor, a serene and cordial man to whom “no hint of night or nature [is] without its charm and its significance.” Thoreau also turns up in Moods in the guise of Adam Warwick, a “violently virtuous” soul who “always take[s] the shortest way, no matter how rough it is.” Thoreau also supplies the basis for a main character in Alcott’s other adult novel, Work, as does the lesser-known transcendentalist Theodore Parker, a radical Unitarian minister who helped finance John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and who rallied Louisa out of a nearly suicidal depression when she was twenty-five.

Yet of all the Concord and Boston literati, it is Bronson Alcott himself who figures most prominently as an ideological inspiration for his once-wayward daughter. For at least fifteen years, Louisa intended but never succeeded in writing a novel about her father’s strivings and misfortunes, which she meant to call “The Cost of an Idea.” As it turned out, her best representation of him in her fiction was the “funny match” that she made for Jo March in Little Women: the educational pioneer Professor Bhaer, who, like Bronson “was poor, yet always appeared to be giving something away . . . no longer young,—but as happy-hearted as a boy; plain and odd, —yet his face looked beautiful to many.” In Plumfield, the academy founded by Jo and the Professor at the end of Little Women and that supplies the milieu for Little Men and Jo’s Boys, Alcott deftly combines a pastoral setting reminiscent of Fruitlands with the progressive, morally directed curriculum of her father’s early schools. When asked to write a preface to a book about the short-lived but influential Temple School, which Bronson had founded in Boston when she was a toddler, Louisa wrote: “As many people . . . inquire if there ever was or could be a school like Plumfield, I am glad to reply by giving them a record of the real school which suggested some of the scenes described in Little Men. . . . Not only is it a duty and a pleasure, but there is a certain fitness in making the childish fiction of the daughter play the grateful part of herald to the wise and beautiful truths of the father.”

After books like Little Women, An Old-Fashioned Girl, and Little Men had banished economic distress from her life forever, Louisa May Alcott could only look back with bemusement on the peculiar path she had followed, to becoming for a time the most popular author in America. “Life,” she told her journal in 1874, “always was a puzzle to me, and gets more mysterious as I go on. I shall find it out by and by and see that it’s all right, if I can only keep brave and patient to the end.” When that end came fourteen years later, it came no less strangely than anything that had gone before. Bronson, who had long since set aside all his early disapproval of Louisa and had at last embraced her as “Duty’s Faithful Child,” suffered a massive stroke in 1882. He was fading rapidly at the start of March 1888, when Louisa came to see him for the last time. Observing a smile on his face, Louisa asked about its cause. “I am going up,” her father replied. He then added a macabre invitation: “Come with me.” Louisa answered, “I wish I could.” On March 4, Bronson Alcott died. The same day, without having learned of her father’s passing, Louisa lay down for a nap and only briefly regained consciousness. Her doctor diagnosed an apoplexy. Two days later, on the day of her father’s funeral, she did, indeed, “come up.”