“Hate keeps a man alive.”

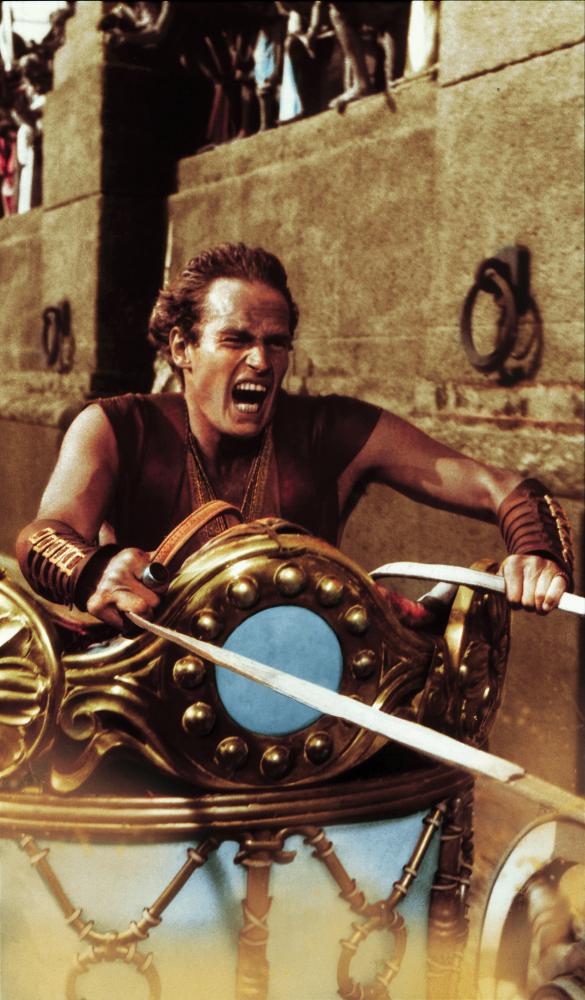

Those famous words do not actually appear in the original 1880 novel Ben-Hur by General Lew Wallace. Karl Tunberg, or more likely Christopher Fry or Gore Vidal (there was a dispute over the screenplay credit), gave that line to Roman patrician Quintus Arrius as he confronted the magnificent, nearly-naked galley slave Judah Ben-Hur, played by Charlton Heston, in the 1959 Hollywood blockbuster. The film cost MGM $15 million to make, won the studio a record eleven Oscars, and was seen by ninety-eight million people in cinemas across the United States. It was the only Hollywood movie to make the Vatican’s official list of approved religious films, and, like clockwork, it is rebroadcast on network television every Easter. And yet the movie’s acclaim still does not compare to the waves of religious ecstasy that followed the publication of the novel, which is the most influential Christian book written in the nineteenth century.

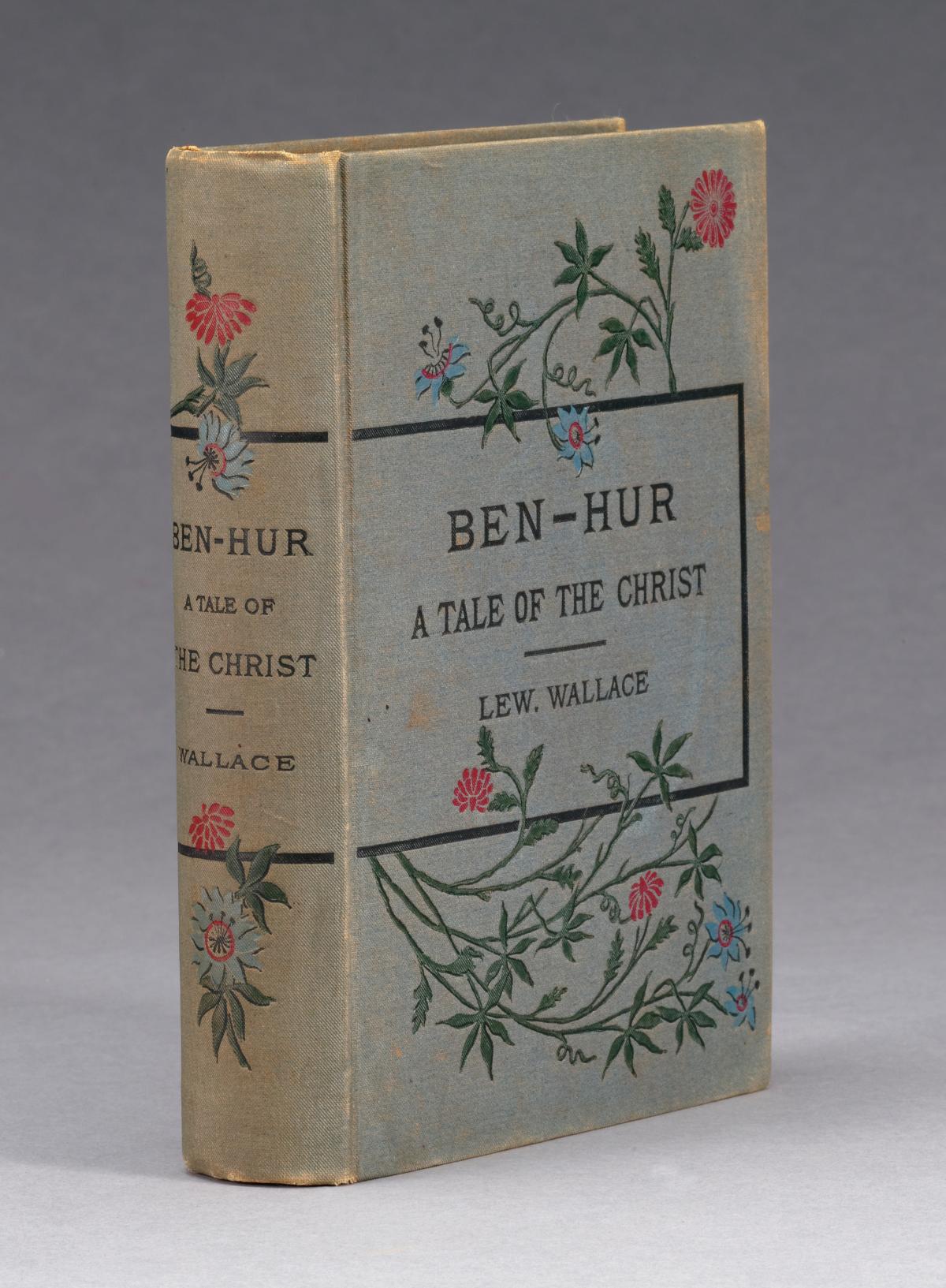

Since its first publication, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ has never been out of print. It outsold every book except the Bible until Gone With the Wind came out in 1936, and resurged to the top of the list again in the 1960s. By 1900 it had been printed in thirty-six English-language editions and translated into twenty others, including Indonesian and Braille.

The novel intertwines the life of Jesus with that of a fictional protagonist, the young Jewish prince named Judah Ben-Hur, who suffers betrayal, injustice, and brutality, and longs for a Jewish king to vanquish Rome. It has the appeal of a rollicking historical adventure combined with a sincere Christian message of redemption.

Victorians who swore off novels because of their immoral influence eagerly picked up Ben-Hur—were even encouraged to by their pastors. It became required reading in grade schools across the United States. For those who considered theater sinful, the spectacle of the Broadway version lured them in for twenty-one years, not to mention the touring show that required four entire trains to transport all the scenery and livestock. More than twenty million people saw Ben-Hur on stage between 1899 and 1920, complete with live horses running on hidden treadmills to recreate the chariot race. One reverend from San Francisco, who had never attended a play, was finally tempted into seeing the much-hyped production. He described the experience as both “delightful and disappointing,” noting the clunky stagecraft and stilted acting. Yet he was won over enough to declare that he would return to the theater again.

The book made Lew Wallace a celebrity, sought out for speaking engagements, political endorsements, and newspaper interviews. “I would not give a tuppence for the American who has not at least tried to do one of three things,” Wallace told a New York Times reporter in 1893. “That person lacks the true American spirit who has not tried to paint a picture, write a book, or get out a patent on something.” Or, he added, “tried to play some musical instrument. There you have the genius of the true American in those four—art, literature, invention, music.”

Not coincidentally, Lew Wallace himself excelled at all four. Besides being a Civil War hero, the governor of New Mexico, and later the ambassador to Turkey, the Indiana native made and played his own violins, sketched and painted with skill, and held eight patents for various inventions, including a retractable reel hidden inside a fishing rod handle. But it was in literature that Wallace truly made his mark. He is the only novelist honored in the National Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol. With a life full of distinctions, none of Wallace’s accomplishments made such an impression as his novel Ben-Hur. In its writing, Wallace’s life was transformed.

Born in 1827 in Brookville, Indiana, Wallace’s childhood was shaped by the death of his mother when he was seven, his father’s service as governor beginning when he was nine, and an aptitude to ignore his studies. “My rating at school was the worst; yet, strange to say, education went on with me, for I was acquiring a habit of reading,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Looking back to the thrashings I took stoically and without a whimper, I console myself thinking of the successful lives there have been with not a jot of algebra in them.” He did have interests, even if they weren’t academic; young Wallace was known to steal household supplies to outfit his secret art studio, and his tutor encouraged his early efforts at story writing.

At sixteen, Wallace’s father kicked him out of the house and sent him off to earn a living, hoping to steer him away from art and other delinquent tendencies. And it seemed to work. At nineteen, Wallace went to fight in the Mexican War. He returned a veteran, a respectable member of society, and as a young lawyer strove to win the favor of his future wife, Susan Elston, sister-in-law of U.S. Senator Henry S. Lane of Crawfordsville, the “Athens of Indiana.” The town acquired the nickname because of its prominent citizens, such as Lane, who helped found the Republican party, and the intellectual community of Wabash College, founded in 1832. Susan would prove to be an invaluable partner to Wallace as a sounding board and editor. She was a writer in her own right, publishing six books (two were illustrated by Wallace), including much poetry. She gave to American literature the phrase “the patter of little feet.”

As the Civil War commenced, Wallace was again called to duty. He rose through the ranks quickly and at thirty-four became the youngest man in the Union Army to achieve the rank of Major General. But he was scapegoated for the huge losses at Shiloh, where thirteen thousand Union soldiers died in 1862, the largest toll then seen in the war. On Grant’s orders, Wallace had marched the Third Division of the Army of the Tennessee and its artillery through six miles of mud, only to arrive a day late to the battle. Soon after, Wallace was relieved of his command. Later, he redeemed himself at the Battle of Monocacy, where he was able to hold off the Confederate army long enough to prevent the capture of Washington, D.C.

Coming home, he found himself dissatisfied with his early careers as a soldier, politician, and lawyer (the last he described as “that most detestable of occupations”) and began writing in earnest again. He had his first novel, The Fair God, published in 1873. A tale about the conquest of the Aztec Empire by the Spanish, its inspiration came from Wallace’s reading of William Prescott’s Conquest of Mexico and from his own experiences there.

Inspiration for Wallace’s next project, what would become Ben-Hur, came from an unlikely source: his own ignorance. Wallace often told the story of how in 1875 he met on a train the well-known agnostic Colonel Robert Ingersoll. After hours of conversation in which Ingersoll questioned the evidence for God, heaven, Christ, and other theological concepts, Wallace came away realizing how little he knew about his own religion. “I was ashamed of myself, and make haste now to declare that the mortification of pride I then endured . . . ended in a resolution to study the whole matter, if only for the gratification there might be in having convictions of one kind or another.”

So began Wallace’s journey into the world of first-century Judea. In true lawyer style, he hit the books: First the Bible, and then every reference book about the ancient Middle East he could find. He suspected that a novel about Jesus Christ would be scrutinized by experts, so the plants, birds, clothes, food, buildings, names, places—everything had to be exact. “I examined catalogues of books and maps, and sent for everything likely to be useful. I wrote with a chart always before my eyes—a German publication showing the towns and villages, all sacred places, the heights, the depressions, the passes, trails, and distances.” He traveled to multiple libraries across the country to ensure he had the exact measurements for the workings of a Roman trireme. He provided detail after detail on the design of Persian versus Greek versus Roman chariots. He did everything short of going to Jerusalem himself. Years later, when he actually visited the Holy Land, he tested his research and proudly said, “I find no reason for making a single change in the text of the book.”

Wallace’s meticulous descriptions of the ancient world gave the story an immediacy often lacking in typical toga novels. He broke with myth and opted toward accuracy. There is no manger in a barn in this nativity scene. Instead, Wallace put it correctly in a cave, the last shelter available at the khan for Bethlehem’s stragglers. He goes to great length describing the khan, an inn of sorts named for its Persian origins, which was mostly an enclosed area chosen for shade and water. “Lodging the traveler was the least of their uses; they were markets, factories, forts; places of assemblage and residence for merchants and artisans quite as much as places of shelter for belated and wandering wayfarers.”

In another familiar Biblical scene, on the banks of the Jordan, where John the Baptist blesses Jesus, we see the scene through the eyes of Ben-Hur, who is suspicious of the unwashed, unkempt John and also of a supposed king dressed as a modest rabbi and covered in dust. “Despite his familiarity with the ascetic colonists in En-Gedi—their dress, their indifference to all worldly opinion, their constancy to vows which gave them over to every imaginable suffering of body . . . still Ben-Hur’s dream of the King who was to be so great and do so much had colored all his thought of him.” Like many, he expected to see heralds and courtiers like those in Rome and was confused by what was actually in front of him.

Wallace placed the chariot race in the circus in Antioch (the1959 film located the race in Jerusalem, a city that never actually held a stadium). He devoted four pages to the arena’s description, and explained how, like a scoreboard for everyone to see, the officials marked the progression symbolically, by removing large wooden balls and dolphins from each end of the course after each turn of the race. Sometimes Wallace spoke directly to the reader: “Let the reader try to fancy it; let him first look down on the arena, and see it glistening in its frame of dull-gray granite walls; let him then, in this perfect field, see the chariots, light of wheel, very graceful, and ornate. . . . let the reader see the accompanying shadows fly; and, with such distinctness as the picture comes, he may share the satisfaction and deeper pleasure of those to whom it was a thrilling fact, not a feeble fancy.”

The chaos erupting in Jerusalem during the last three days of Jesus’ life is palpable in the novel. Ben-Hur frantically catches bits of information and gossip, and not knowing how it will end or what to make of it. He sees his army of Galileans disillusioned and dispersed, while his fiancée turns on him, denouncing his lack of ambition and abandoning him for his enemy. He wrestles with his heart over a man who can cure lepers but won’t protect himself. As Ben-Hur guided readers through the scenes of the Passion, so did he lead the way for Lew Wallace to believe in Jesus Christ. “I have seen the Nazarene,” Wallace told an audience in San Francisco. “I saw him perform works which no mere man could perform. I have heard him speak. I was at the crucifixion. With Ben-Hur I watched and studied him for years, and at last I, too, took the word that Balthasar gave him—‘God.’”

There were so many rumors about Wallace’s faith—that he was an atheist or that he had gone to the Holy Land to disprove the existence of Christ—he felt it necessary to introduce his autobiography by dispelling them. “In the very beginning, before distractions overtake me, I wish to say that I believe absolutely in the Christian conception of God. As far as it goes, this confession is broad and unqualified, and it ought and would be sufficient were it not that books of mine—Ben-Hur and The Prince of India—have led many persons to speculate concerning my creed. . . . I am not a member of any church or denomination, nor have I ever been. Not that churches are objectionable to me, but simply because my freedom is enjoyable, and I do not think myself good enough to be a communicant.”

Despite Wallace’s irreverence toward organized religion, Ben-Hur maintains a respect for the underlying principles of Judaism and Christianity. In the novel it is clear that hate had nothing to do with Ben-Hur’s survival, contrary to Arrius’ assertion. Instead, Wallace intended to show God’s benevolence through the compassion of strangers—one of the strangers being Christ, who gives Ben-Hur water and hope on his march to become a Roman galley slave. Wallace prided himself on scrupulously following the Bible in depicting the words and acts of Christ, except for this one scene. “The Christian world would not tolerate a novel with Jesus Christ its hero, and I knew it,” explained Wallace. “He should not be present as an actor in any scene of my creation. The giving a cup of water to Ben-Hur at the well near Nazareth is the only violation of this rule. . . . I would be religiously careful that every word He uttered should be a literal quotation from one of His sainted biographers.” Since that left a considerable gap of knowledge of about twenty years of Jesus’ life, Wallace centered the plot on a fictional contemporary’s struggles and had Jesus play a cameo role.

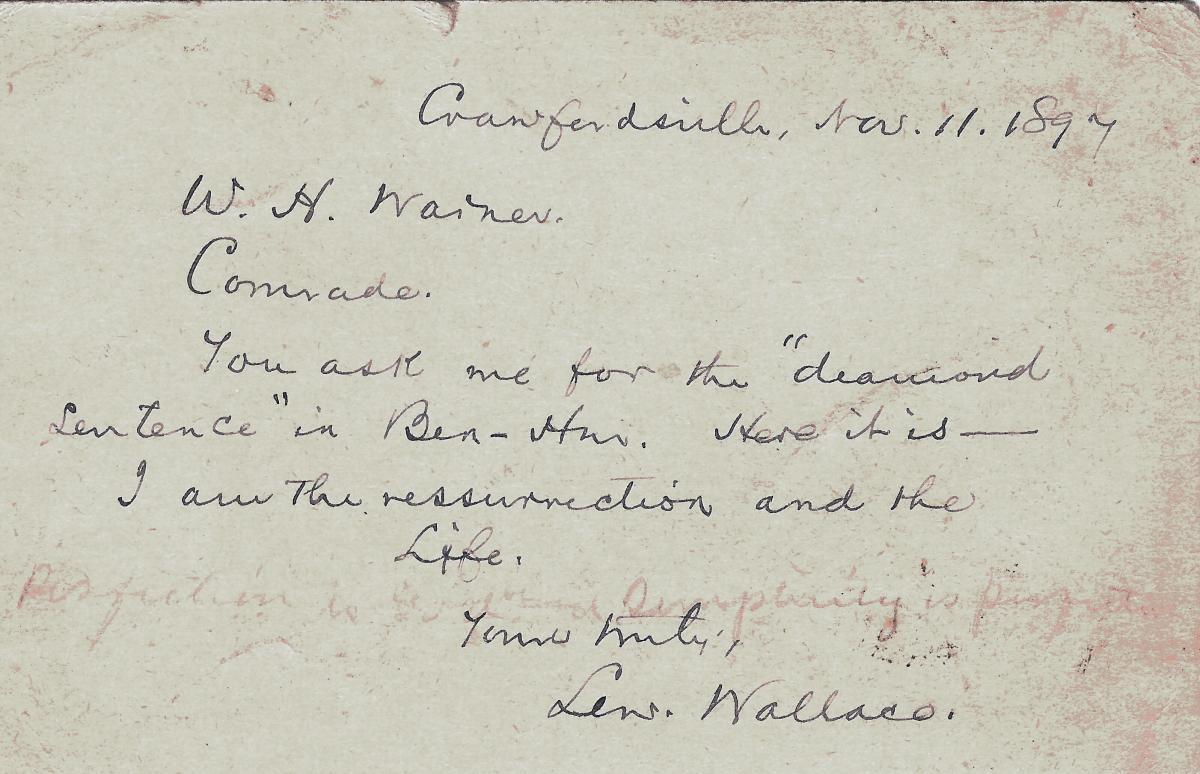

Wallace wrote and wrote and wrote, one day from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., but more often catching moments between his professional commitments—on the train or after work in Crawfordsville under an enormous beech tree. When he was appointed governor of New Mexico—a place detested by his wife who borrowed General Sherman’s quip, “We should have another war with Old Mexico to make her take back New Mexico”—Wallace had to postpone his writing until late at night after fulfilling his executive obligations. “I am trying to do four things: First, manage a legislature of most jealous elements; second, take care of an Indian War; third, finish a book; fourth, sell some mines,” he complained to his wife. Following the Lincoln County War, Wallace granted amnesty to the outlaw Billy the Kid in return for his testimony in court. The deal turned sour when the district attorney refused to set Billy free. He escaped from jail and swore he would “ride into the plaza at Sante Fé, hitch my horse in front of the palace, and put a bullet through Lew Wallace.” Though gangs would shoot out the candles in the ballroom where he wrote, Wallace continued. Finally, he hand-delivered the finished manuscript to Harper and Brothers in New York; it was written in purple ink and praised by Joseph Harper as “the most beautiful manuscript that has ever come into this house. A bold experiment to make Christ a hero that has been often tried and always failed.”

The book was not an immediate success, but within two years it had gained momentum. The same morning President Garfield finished reading it, he wrote a thank-you note to Wallace, and within the month offered him the ambassadorship to Turkey. Ulysses S. Grant confessed he was so absorbed with the story, he read it for thirty hours straight. Fans from around the world wrote to Wallace, recounting their own conversions with Ben-Hur—this one became a missionary, that one claimed the book saved his life. Wallace became so closely linked with Ben-Hur that he no longer went by General, but was referred to as Lew Wallace, author of Ben-Hur. In newspaper articles and at speaking engagements, he was sometimes just called Ben-Hur.

The most vivid scenes in the book are also the spectacular ones from the movie—the Roman fleet’s battle at sea, the chariot race between Ben-Hur and his enemy Messala, and the crucifixion. But Wallace’s favorite scene wasn’t one of thrilling action, or even one where Christ appeared. It is a quiet scene where Ben-Hur tells his friends about the miracles he’s seen Christ perform—from turning water into wine to raising a man from the dead—and asks them what they make of it. Balthasar, one of the original three wise men, replies, “God only is so great.”

“When I had finished that,” Wallace confessed, “I said to myself with Balthasar, ‘God only is so great.’ I had become a believer.”

Ben-Hur Central

A larger-than-life limestone frieze of the face of Judah Ben-Hur—a wholly imagined visage—hovers over the entrance to the General Lew Wallace Study and Museum in Crawfordsville, Indiana.

Finished in 1898, after Wallace’s return from Turkey, the Periclean Greek/Byzantine/Romanesque-style building is more castle than study. Set in the middle of a typical Midwestern small-town neighborhood of Queen Anne and Stick residences, it lords over its enclosed park like a feudal earl surveying his kingdom. The grounds once included a moat stocked with fish, until Wallace realized the hazard it posed to neighborhood children and had it filled in. The reflecting pool is also gone, the copper roof leaks, and the basement transforms into a small river during rainstorms, but the structure retains the image of an exotic retreat that Wallace long dreamed of. “I want a study, a pleasure-house for my soul, where no one could hear me make speeches to myself, and play the violin at midnight if I chose,” he wrote to his wife, Susan, in 1879. “A detached room away from the world and its worries. A place for my old age to rest in and grow reminiscent, fighting the battles of youth over again.”

Tokens from Wallace’s eclectic life are packed into the twenty-five by twenty-five-foot main room of the study. His unfinished painting The Conspirators marks his service as one of the judges for the assassins of Abraham Lincoln. A painting of a young girl—a gift from Sultan Abdul Hamid II—and a tiny embroidered child’s slipper are reminders of his time in Turkey. A box full of violin parts rests under a photograph of Wallace playing to his grandson. A hidden full-length mirror that pulls out from a door jam was used by Wallace to practice speaking; it was also used for an inside joke between Lew and Susan to see which guests would primp in front of it when they held social gatherings in the study.

There is the rocking-chair desk that Wallace fashioned so he could write comfortably outdoors. From his life as a soldier there is a uniform from his 11th Regiment (also known as the Indiana Zouaves), his battle sword, and his lucky buckeye trimmed in silver. Objects from Wallace’s travels, interests, and exploits crowd every available space from floor to ceiling, making this visitor somewhat chagrined by her own lack of industriousness. But the most striking features are the white oak, glass-enclosed bookcases spreading across three sides of the room, still holding Wallace’s personal library. The shelves offer a glimpse into how Wallace spent his free time, from reading the fifty-three volumes of The War of the Rebellion to Sir Edward Creasy’s History of the Ottoman Turks to Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

The back room is all Ben-Hur all the time, showcasing costumes, movie stills, and other items from the films that Wallace never saw. He had been adamantly against the dramatization of his book until stage producer Abraham L. Erlanger convinced him that Jesus would not be played by any actor—Christ would be acknowledged only as a beam of light on stage. Even in the films, the audience never sees his face. Wallace died in 1905 at the age of seventy-seven. Later that same year, his study was opened to the public. Two years later, the first fifteen-minute, unauthorized film version was released and Wallace’s son took up the cause, suing the filmmaker for using the plot and title of Ben-Hur without permission of the author’s estate. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court and firmly established the copyright infringement laws for the movie industry that are still in use today. A synopsis of the ruling hangs on the wall of the Study next to the only extant image from that film, showing the chariot race: All the other prints were destroyed by law. Next to the 1907 print hangs a publicity still of Ramon Novarro playing Ben-Hur in the 1925 movie.

That film was authorized and followed Wallace’s manuscript more closely, even keeping the second part of the novel’s title—A Tale of the Christ. It also kept the role of Iras, the Egyptian princess that never made it into the later version, but she was strangely costumed to look like a young Mae West, in contrast to Esther, who tended more towards the wholesomeness of Mary Pickford. The most expensive silent film of its day, its cast comprised over one hundred thousand actors and extras. MGM head Louis B. Mayer wanted authenticity for the chariot race and offered a $100 cash prize to the winning driver. Of course, that finish would have to end up on the cutting room floor and Ben-Hur’s win inserted instead.

William Wyler was an assistant director for that chariot race. Thirty-four years later, he would direct the talking version starring Charlton Heston—although Burt Lancaster, Rock Hudson, and Paul Newman were first approached to play the lead (Newman declined, saying he didn’t have the legs for it). Heston would be so closely identified with Judah Ben-Hur for the rest of his life that he kept up decades of correspondence with the staff of the Lew Wallace Study, exchanging Christmas and birthday cards. He finally visited the Study in 1983, without pomp or press. The Study proudly displays a photo taken during his visit; it rests opposite the glorious costume Heston wore in the chariot race, in which he famously did his own driving, and according to the script, won handily.