Before Spain was Spain, the Iberian Peninsula was ruled over by a Muslim caliphate, a state of affairs that in the eleventh century gave way to a number of petty kingdoms that functioned like independent city-states. Muslims, Jews, and Christians, for the most part, coexisted peacefully: in fact, the violence arising within the Muslim and Christian communities often exceeded the violence between them. But all three peoples enjoyed a high degree of civilization marked by great achievements in science and art. Still, all was not well. As the balance of power began to shift from Muslim to Christian, a power struggle erupted among Christian rulers that would continue for generations, even as the light of Arabic poetry burned bright enough to influences centuries of Western verse.

Castile’s political history begins in earnest with Sancho the Great, the Christian ruler who in the eleventh century gained control over Aragon, León, Navarre, and Castile during the three decades of civil war that marked the end of Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula. Though it was his aim to supplant the centuries-old Muslim Umayyad caliphate with a new unified Christian and Hispanic kingdom, at his death, Sancho explicitly dismantled that hard-won and still-nascent empire by dividing his realm among his sons. The most successful was his second son, Ferdinand, first king of Castile. Ferdinand assimilated León into his kingdom when he defeated and killed his brother-in-law in 1037; and he proceeded to absorb his own elder brother’s portion, Navarre, by defeating and killing him in battle as well. Once he had consolidated the power and territories that had been dispersed to his brothers, Ferdinand became a key player in the reversal of fortunes between Christian and Islamic petty kingdoms in the eleventh century, leading straight to the pivotal taking of Toledo in 1085.

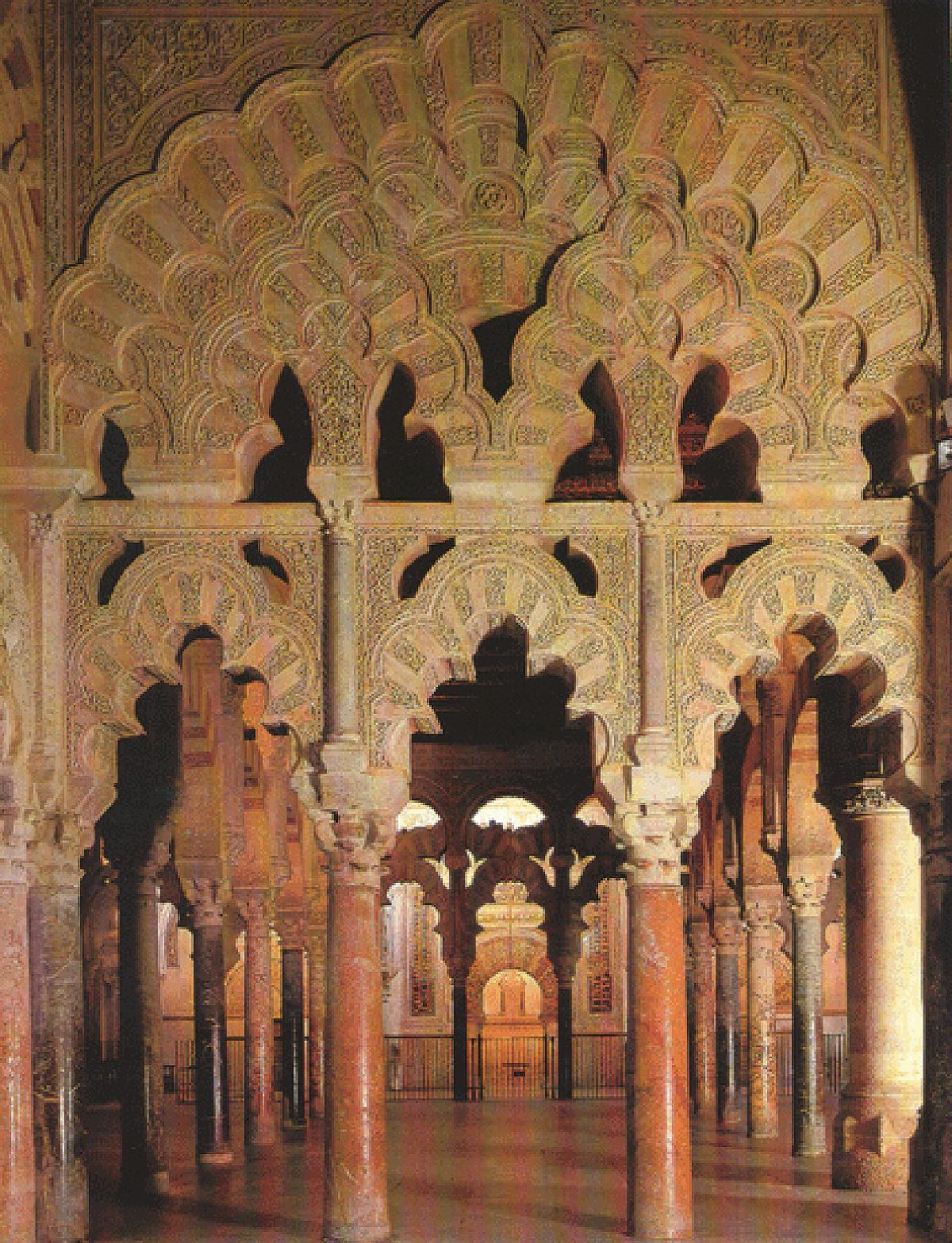

Ferdinand’s successful raids into the territories of various Taifas—small rich Islamic kingdoms—during the 1050s and 1060s, starkly reveal the debilitated military state of the nearly two dozen independent and feuding Islamic city-states. The entrancing paradox of this moment is that mercurial and competitive political circumstances proved a fertile breeding ground for virtually every aesthetic and intellectual endeavor. The small Taifa courts vied with one another for scholarly and artistic achievement, as a way of emulating the lost court culture of Umayyad Cordoba. Seville excelled in poetry, Saragossa in song, Toledo in science, agriculture, and astronomy, though learning, poetry, and song resonated in them all. And each vied with the memory of the Umayyad caliphate, and the legend of Madinat al-Zahra (the planned city built by Abd al-Rahman II in 936 and destroyed in 1010) to create opulent palatial settings in which the fabrics and food and scents of court life became the symbols of sovereignty. But none of that extraordinary Taifa culture—the great new love songs of the moment, the scientific studies, botanical research, and philosophical treatises, the exquisite palaces of Taifa cities like Saragossa—was able to keep these Islamic city-states stable, especially when they were often and viciously turned against each other.

But with Ferdinand’s death, the united Christian kingdom was once again willingly sundered. Just like his father before him, Ferdinand divided his hard-won realm into three; a share for each of his sons. Sancho, the oldest, received Castile, and the youngest, García, inherited the westernmost kingdom of Galicia. And in another, perhaps less conscious imitation of his father, Ferdinand favored his own second son and gave León, the richest share by many measures, to Alfonso.

The complex tale of bad fraternal blood that followed the partition of Ferdinand’s kingdom among his three sons echoed that of the generation before. Here in this generation, the two oldest brothers—Sancho of Castile and Alfonso of León—coveted the lands of the youngest—García—and sought to run him out of his kingdom, but eventually turned against each other as well. In 1071, in response to Alfonso’s growing influence in Galicia, Sancho invaded León, and defeated his brother Alfonso at the battle of Golpejera. Sancho thus fleetingly reunited León and Castile under his scepter, and he sent Alfonso to Burgos in chains. Sancho consolidated his power by vanquishing his youngest brother, García, king of Galicia, whom he packed off in exile to the Taifa of Seville. And that is how García became the guest of the great Taifa ruler—and poet—al-Mutamid. He sat in elegant colonnaded courts on silk cushions, each textile worth a fortune by Castilian standards; he walked in irrigated gardens near the Guadalquivir River with what must have seemed like wondrous fountains. And he heard an entire court spar, negotiate, jest, and make love in poetry.

Alfonso was imprisoned because he had posed far more of a threat to Sancho’s growing power than García. But as Sancho managed to appease the denizens of the kingdom of León, which he had appropriated from his brother, he relented to the pleas and counsel of his sister Urraca and Abbot Hugh of Cluny, and sent Alfonso from his prison in Burgos into exile in Tulaytula, the Taifa of Toledo. And how Alfonso must have marveled, emerging from a dark bastion in Burgos into the brilliant palaces of Toledo. With al-Mamun, the king of the Dhu al-Nunid family, Alfonso experienced a Toledo far more cosmopolitan and glorious than the celebrated Toletum of the Visigothic monarchy. He attended court banquets in columned palaces where guests received silk perfumed robes, or played a game like manqala with priceless carved ivory gameboards.

Like his younger brother in Seville, he also heard poetry, and wandered in pleasure gardens on the edge of town that were planted with exotic flowers and fruits studied and nurtured by court botanists and agronomers. The exiled Alfonso, an ex-king without portfolio, watched Mozarabic craftsmen, Jewish physicians, and Muslim astronomers interact in a lively court culture with al-Mamun—his old feudal client—the uncontested ruler of a city where sovereignty meant authority over multiple peoples and a multitude of arts and sciences as well. And thus, ever more distinctively part of the Castilian story too were the Taifa cities, and increasingly commonplace in everyday life were entanglements with Muslims, in war and love and a great deal in between.

Alfonso’s brief Toledan exile, like his brother’s in Seville, bears witness to the fungibility, and volatility, of political alliances and enmities, as well as shared cultural values and latent cross-religious intimacies. Decades after the scattering of the old caliphate, and with the consequent unfurling of a Christian presence, fraternization was exponentially more accessible, frontiers more porous. Alfonso’s fugitive stay in the great Islamic metropolis of Tulaytula provided a poetic augury, a kind of dramatic antechamber, to what would be the cardinal event of the century: his conquest of that same Toledo some fifteen years later. To master one of the great Taifas was an ambition some medieval historians believed Alfonso first dreamt of while he was al-Mamun’s guest, in the great Taifa king’s exceptional palaces. This may have been true—although in 1071 Alfonso was hardly in a position to aspire to anything so audacious, scarcely more than his brother’s political prisoner, even if it was in the supremely gilded cage of Tulaytula where he was confined.

Within a couple of years the political landscape was transfigured by two theatrical political assassinations. In 1072 the ascendant and powerful brother Sancho was betrayed and murdered outside the walls of the city of Zamora. In the aftermath, with his brother and principal rival for control of the Christian kingdoms dead, Alfonso emerged from his Toledan exile within spitting distance of the kind of unified control his father, and grandfather before him, had carved out. Indeed, Alfonso commanded the loyalty of nobles from all three kingdoms before García could ride north from Seville. Just a few years later, the same al-Mamun who had been Alfonso’s protector and host was assassinated. He was ultimately succeeded by a grossly corrupt and ineffective grandson named al-Qadir, who would be the last Muslim ruler of Toledo.

In May of 1085 Alfonso VI took possession of the city of Toledo without resistance. As part of the terms of surrender, he sent his own troops to install his predecessor, the hapless al-Qadir, on the throne of Valencia, and he also promised the Muslim inhabitants of Toledo physical security, freedom of worship, the right to their own properties, and the unmolested use of their Friday mosque. What Alfsonso negotiated in this elegant dance of shifting power was a pact drawn from important parts of the dhimma, a way of subduing a plural city learned from his Muslim allies.

Though many Jews and Muslims left Toledo in the wake of the conquest of 1085, this city was far from an empty shell. One of Alfonso’s first goals was, in fact, to retain its population, in order to stabilize its demography and economy, while carving out a place for the Castilians and the Franks who swept in with him. What they found was a metropolis with a mix of all the children of Abraham, who intermingled in those civic and commercial spaces. Some Christians and many Jews had held governmental posts in Taifa kingdoms, and they comingled with Muslims socially and even in education. They had seen each other in the streets, the markets; and they could even use the same public baths.

In the pact that gave him Toledo, Alfonso had appropriated the places that excited wonder in the minds of the Castilians—the palace of the Taifa kings, the treasury of al-Qadir, and the royal gardens. Part of the bequest of those palaces was a culture of poetry and song, to which the Castilians, long before 1085, had hardly been strangers. Among other things, Count Sancho García of Castile has received a gift from the Umayyads of qiyan, female performers whose song repertory consisted of hundreds of lyrics. And in the Taifa city that became the trophy bride for the Castilians, her fine homes and courtyards still resonated with the sounds of that immense poetic dowry. Yet long before Toledo’s Taifa palaces and their gardens were lost by al-Qadir, and became a part of the very center of Castile, nostalgia and loss already permeated Arabic poetic culture. In the memory inscribed in Andalusian Arabic poetry, no lost gardens are better remembered than those of the palace city of Madinat al-Zahra, sacked during the civil wars that brought the Umayyad caliphate to an end. In the efflorescence of poetry that made the Taifas a glorious literary era, the memory and the ruins of the lost gardens of Cordoba play an elegiac role.

With passion from this place, al-Zahra,

I remember you.

Horizon clear, limpid

The face of earth, and wind,

Come twilight, desists,

A tenderness sweeps me

When I see the silver

Coiling waterways

Like necklaces detached

From throats. Delicious those

Days we spent while fate

Slept. There was peace, I mean,

And us, thieves of pleasure.

Now only flowers

With frost-bent stems I see . . .

Trans. Christopher Middleton and Letitia Garza-Falcón

Thus begins one of the many eloquent love poems—a formal qasida, or ode, the elemental poetic form in classical Arabic—by Ibn Zaydun, a Cordoban who was born into the crumbling Umayyad universe, in 1003, and died in Seville, in 1070, one of the most famous poets of an age famous for its poets. This was a culture in which, from pre-Islamic times on, to speak Arabic was no less to speak its poetry, to know the canon and its great figures, its clichés and its masterpieces. Even in such a poetry-besotted universe Ibn Zaydun was particularly revered for his love poems, as he is to this day in the Arabic tradition. In the eleventh century, not only among the citizens of Taifas like Toledo, but far beyond, the Cordoban poet is the supreme craftsman of the particular branch of love verses that glorify longing itself. The bed of this wide and deep poetic stream is defined by its cultivation of an aura of love as that which can never be possessed.

Is Ibn Zaydun here, in this ode known as “From al-Zahra,” really lamenting the loss of his beloved Wallada? Wallada was the brilliant and sharp-tongued Umayyad princess who was born toward the end of the caliphate and lived to be part of Taifa culture through her own life and poetry. Heir to the Umayyads’ Navarrese white skin and blue eyes, Wallada refused to wear the veil when walking in the city, it was said, in order to flout her beauty. She was also notorious for the freedom of her amorous adventures, about which she wrote her own often scathing verses; the most famous of her liaisons was with Ibn Zaydun, charted in dozens of his poems, and mythologized as a species of Romeo and Juliet in the annals of Arabic literature. But Ibn Zaydun’s lament also remembers the terrible loss of the Umayyad universe itself, evoked as the ultimate paradise lost. In the ambivalence between place and beloved lies much of the force of the desire: There are perhaps always multiple loves and moments evoked by such a chimerical place of happiness and peace, now abandoned.

Ibn Zaydun’s personal history, as it happens, presents a vivid example of this enmeshment of the political and the personal. The historical record speaks to his passionate political entanglement with Cordoba itself, in its painful last years, and his devotion to the lost Umayyad cause; and no less so to Wallada, who not only abandoned him but reviled him for infidelity in her own verses and then took his great rival, the court vizier Ibn Abdus, as her lover—which in turn led to Ibn Zaydun’s imprisonment. It is a life story in this respect not unlike that of his equally famous Cordoban contemporary Ibn Hazm, who also crafted visceral evocations of passion, and its perils.

How I wish I could split my heart

with a knife

put you inside

then close up my chestso that you would be in my heart

and not in another’s

until the resurrection

and the day of judgment.There you would stay while I lived

and after my death

you would remain buried deep in

my heart

in the darkness of the tomb.

Trans. Cola Franzen

Ibn Hazm was the towering figure of Andalusian letters of his age: a polymath, an important legal scholar, and a prolific and powerful writer who, in ways different from but parallel to Ibn Zaydun, dominated the intellectual landscape of the Taifas. And like Ibn Zaydun, Ibn Hazm was born into the chaos of the final days of the caliphate, in 994; worked tirelessly for the hopeless Umayyad cause; and then spent the rest of his life in embittered exile, wandering through Taifa al-Andalus until he died in 1064, in Niebla, not far from Seville. His most famous book is a treatise on love and its poetry, Tawq al-hamama (The Dove’s Neck-Ring), which serves also as a chronicle of the last gasp of Umayyad culture. His most poignant chapter is the one titled “On Separation,” with its description of many kinds of losses, among the most searing that of a particularly cherished beloved, a slave girl named Num: “Destiny deprived me of my beloved when the nights carried her away and days passed by, and she became one with the dust and the stones. . . . My love for her obliterated everything that came before her, and nullified what came after her.” Only a few pages after this is his searing and echoing description of the loss of his childhood home in Cordoba: “Its traces had been erased, its signs obliterated, its location hidden. Now it was all rot: it had become a barren desert, having once been a flourishing land; a desolate expanse in the wake of happy companionship; the shattering of great beauty, fright-filled roads after safety; a refuge for wolves, a carousing spot for ghosts, a playing for jinn, a lurking place for wild beasts.”

Both Ibn Hazm’s little book and Ibn Zaydun’s corpus of love poems achieved the broad power and influence they did because of a far-flung appetite for a copious language of love, an appetite powerfully aroused among neighboring Romance speakers in the decades that followed. It is true that the conflation, in both Ibn Hazm and Ibn Zaydun, of love and history speaks with special pathos to the circumstances of their lives, and to a historical moment: the eleventh century into which the Castilians made their splashy entrance, where Cordoba was already a ruin—its precious Madinat al-Zahra literally so, and Umayyad political omnipotence and cultural supremacy figuratively so. But it is also true that was already a tradition in al-Andalus, whose foundational poem can be said to be the nostalgic ode to a palm tree—to a country palace, and beyond that to a lost world—written by Abd al-Rahman I, the first emir of Umayyad Cordoba.

A palm tree stands in the middle of Rusafa,

born in the West, far from the land of palms.

I said to it: How like me you are, far away and

in exile,

in long separation from family and friends.

You have sprung from soil in which you are a

stranger;

and I, like you, am far from home.

Trans. D. F. Ruggles

Exile, of course, is scarcely distinguishable from the separation of lovers, and from the longing for what cannot be recovered. Ibn Zaydun’s poems evoke places and times that the human heart yearns for, delicious days while fate sleeps, and where one can steal unblemished pleasure. But the role of love poetry is not really to dwell in the satisfaction, let alone wallow in those moments, which turn out, inevitably, to be fleeting, or perhaps illusory, but rather to evoke the longing itself, the homesickness. Perhaps all such places exist only in those traces that remain in the landscape of the imagination, the triggers of vivid memory of what is lost, the flowers a little damaged, with frost-bent stems. The ode “From al-Zahra” finishes like this:

Pure love we once exchanged,

It was an unfenced

Field and we ran there, free

Like horses. But alone

I now lay claim

To have kept faith. You left,

Left this place. In sorrow

To be here again,

I am loving you.

Ibn Zaydun’s poetry is exemplary of many of the paradoxes of the cosmos of the Taifas, and his love songs—and the powerful traditions within which they are embedded—prominent among the cosmopolitan riches that lay inside Toledo. As a poet he occupies all sorts of privileged places at once, perhaps not least in the impartially written history of love poetry in Romance. At the historic center of that narrative sit the troubadours of nearby Langue d’Oc, who began writing their own passion-centered poems in their own newly minted vernacular, in the wake of Toledo’s absorption into the Castilian orbit. In that realm, the nature of ties and contacts between speakers of Arabic and Romance, and thus between their respective poetic traditions—the first at one of its marvelous peaks, in Seville, the other in its glorious infancy, a few hundred miles away—lies at the heart of the universe from which modern western love poetry springs. It is a universe full of riddles, of which perhaps the most vexing is why the Castilians, who encountered this powerful and omnipresent poetic culture head-on, did not themselves cultivate lyric poetry.

Against the backdrop of the conspicuous absence of a love lyric in the vernacular of the Castilians, Ibn Zaydun’s poems stand out as ghostly mementos, markers of a passage from Arabic into the western poetic consciousness, like a delta that spreads from the Taifas northward, hugging the Mediterranean as it spills beyond Valencia and Saragossa and Barcelona, beyond the Pyrenees, into the heart of what we used to call Provence. Although there are no written translations of Ibn Zaydun’s poetry into Romance by his contemporaries, his body of work provides near-perfect examples of all the tropes and sentiments that become the hallmarks of troubadour poetry: the conceit of pure love; the lovesickness that follows, and the wallowing in whatever the opposite of calm is.

In the canon of Arabic poetry, which is filled from beginning to end with poetry of longing and passion, Ibn Zaydun is remembered as one of the greatest masters. No monument in the whole panorama of Arabic love poetry is more revered than his long qasida commonly called the “Nuniyya” for the distinctive rhyme in n (or na, the first-person plural pronoun) that carried its full fifty-two verses. And perhaps no monument commemorates the time and place better than this poem, with its transcendent evocation of loss, which we cite only in fragments:

Morning came—the separation—

substitute for the love we shared,

for the fragrant of our coming together,

falling away.The moment of departure

came upon us—fatal morning.

The crier of our passing

ushered us through death’s door. . . .Keeping faith in you,

now you are gone,

is the only creed we could hold,

our religion. . . .Do not imagine

that distance from you

will change us

as distance changes other lovers.

Trans. Michael Sells

First brought out of the pre-Islamic deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, the art of making great poetry was the cornerstone of culture itself, a culture of poetic champions, the men who were winners of the prestigious competition at the heart of Mecca, where banners were embroidered with the winning poems and hung around the Kaaba, the building in the center of Mecca. The signature motif and characteristic opening of this bedrock body of poems (qasidas called muallaqat, or “suspended ones,” in an allusion to the annual ritual at Mecca) is the poet’s discovery of the abandoned campsite of the beloved’s tribe, which has moved on, in the desert. No one describes their ethos better than the preeminent translator of much of the Arabic canon, Michael Sells: “Traces of an abandoned campsite mark the beginning of the pre-Islamic Arabian ode. They announce the loss of the beloved, the spring rains, and the flowering meadows of an idealized past. Yet they also recall what is lost—both inciting its remembrance and calling it back.”

The Prophet’s own recitations of God’s revelation—Quran literally means “Recitation” and its opening verse is the angel Gabriel’s injunction to Muhammad to “Recite in the name of your Lord who created you”—were overflowing with hermeticisms and flights of poetic beauty. This was especially true of the early suras, or verses, from the years in Mecca, in the first difficult years of his prophethood, before the flight to Medina (the hijra) in 622 CE. They earned Muhammad the accusation that he was just another poet. And although the Revelation he recited to the Arabian tribes soon enough led to the destruction of their old gods, and although the expansion of the Arabs out of the peninsula was a direct consequence of the conversion to that new faith, the old poetic universe was hardly left behind. “If as a revealed text the language of the Qur’an is divine or prophetic, it is at the same time poetic, using the very language of pre-Islamic poetry,” as we are reminded by Adonis, the most influential Arab poet of our times. Even though it is the most powerful icon of the jahiliyya—the “age of ignorance” before Muhammad and the monotheism he preached—pre-Islamic poetry is fully absorbed into Islamic culture, which explicitly embraces as axiomatic the principles of the muallaqa, not just its formalities and its imagistic language, but perhaps more importantly the very notion that language and poetry are the heart of civilization itself.

Even the Quran, and its exegetical traditions, cannot avoid speaking to the provocative question of the relationship between its own poetic language and the formative poetic tradition that precedes it and with which it is intertwined. In sura 26, “The Poets,” the distinction is drawn between the God-given eloquence of the Arabic of revelation and the verse of the poets, whose followers go astray. Most famously, out of sura 11 (which begins with the verse “This is a Book whose verses are indeclinable and distinct”) and also sura 17 (which includes the verses “Surely if men and jinns [genies] get together to produce the like of this [Quran] they will not be able to produce the like of it”) emerges the notion of the miraculousness of the Quran itself, its inimitability. In other religions prophets have proffered other kinds of miracles, but in Islam the miracle is the language of revelation itself.

The conquest of the Iberian Peninsula was military and religious, but it was no less the triumph of the “pennants of the champions,” as one of the surviving anthologies of the poetry of al-Anadalus and the Taifas is called. And as far from pre-Islamic Arabia as late eleventh-century Toledo was, the streets in 1086 still echoed with the sounds of its poetry. One portion of that heritage was the rich poetry itself, and one part the notion of championship as rooted in how brilliantly a man (and the occasional woman) could add to the tradition that tied them directly to the desert poets of the centuries before the coming of Islam, and beyond them to other Islamic courts across time and space, from Umayyad Damascus to Abbasid Baghdad. And to Cordoba, which was already an abandoned campsite, the ruins of Madinat-al-Zahra its traces.

Excerpt from The Arts of Intimacy: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the making of a Castilian Culture, copyright © 2008 by Jerrilynn D. Dodds, María Rosa Menocal, and Abigail Krasner Balbale. Published by Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission.

“From al-Zahra” copyright © 1993 by Christopher Middleton and Leticia Garza-Falcón. From Andalusian Poems translated from the Arabic by Christopher Middleton and Leticia Garza-Falcón. Reprinted by permission of David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc. “A palm tree stands in the middle of Rusafa” translated by D. F. Ruggles and “The Nuniyya” translated by Michael Sells from The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature: The Literature of al-Andalus, copyright © 2000 by Cambridge University Press. Reprinted by permission. “Split My Heart” translated and copyright © 1989 by Cola Franzen in Poems of Arab Andalusia, City Lights Publishers, San Francisco. Reprinted by permission of the translator.

The Treaty of Tudmir

The following letter from April 713 is the earliest preserved terms of capitulation from a Muslim commander to a Visigothic ruler in Iberia. Known as the Treaty of Tudmir, an Arabization of Theodemir, the name of the Visigothic ruler of Murcia, it displays many of the hallmarks of a dhimma arrangement. It provides the local Christian population with freedom to continue practicing their faith, in exchange for loyalty to the ruling Muslims and the payment of yearly taxes.

In the name of God, the merciful and compassionate.

This is a document [granted] by Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa ibn Nusair to Tudmir, Son of Ghabdush, establishing a treaty of peace and the promise and protection of God and his Prophet (may God bless him and grant him peace). We will not set special conditions for him or for among his men, nor harass him, nor remove him from power. His followers will not be killed or taken prisoner, nor will they be separated from their women and children. They will not be coerced in matters of religion, their churches will not be burned, nor will sacred objects be taken from the realm, [so long as] he [Tudmir] remains sincere and fulfills the [following] conditions that we have set for him. He has reached a settlement concerning seven towns: Orihuela, Valentilla, Alicante, Mula, Bigastro, Ello, and Lorca. He will not give shelter to fugitives, nor to our enemies, nor encourage any protected person to fear us, nor conceal news of our enemies. He and [each of] his men shall [also] pay one dinar every year, together with four measures of wheat, four measures of barley, four liquid measures of concentrated fruit juice, four liquid measures of vinegar, four of honey, and four of olive oil. Slaves must each pay half of this amount.