“You know what work is—if you're / old enough to read this you know what / work is,” wrote Philip Levine, in a poem about lining up with other men, outside, looking for work. The poem is called “What Work Is,” and in it Levine momentarily thinks he sees, a few places down the line, his own brother. But it cannot be so, for his brother, he knows, is home sleeping off the night shift he works at the Cadillac factory; soon the brother will wake up to study German and practice singing Wagner. The poet loves his brother and is struck by the seriousness of his character.

It is a favorite poem of mine, though I always found it odd how it shifts from the grittiest kind of labor to one of the highest forms of art. This issue of Humanities, however, has changed my perspective. Departing NEH chairman, Bruce Cole notes in the Conversation that art-making in the Renaissance was a trade like that of the butcher and the baker. One became an artist for the simple reason that your brother or your uncle ran a shop and you could get work there. Art-making was a blue-collar business.

The art, itself, was, of course, majestic and religious. Things change, though. Today, it is the artist who seems majestic, while the art bears little connection to organized religion.

This can be seen in modern art, as James Panero’s article on “The Third Mind,” the exuberant show of Asian-inspired modern art at the Guggenheim in New York makes clear. Work and art also figure prominently in this issue’s essays on the historian Thomas Carlyle, poet Elizabeth Bishop, and the visual art of the Bloomsbury set.

Carlyle, the great Victorian chronicler of the French Revolution, would steep himself in his reading and then “write like mad,” Meredith Hindley notes in her essay. Such was his preparation to turning the revolution into a full-sensory experience, as he strove to put readers within sniffing distance of the guillotine.

Poet and literary scholar Carol Frost goes searching for the key to Bishop’s most famous poetic work, “The Fish,” in the Florida Keys, resolving to identify the exact species Bishop had in mind. Imagination is at work, too, in Steve Moyer’s article on Bloomsbury art, where an American collector is quoted wondering if the American taste for Bloomsbury paintings might be explained by the work ethic of the artists.

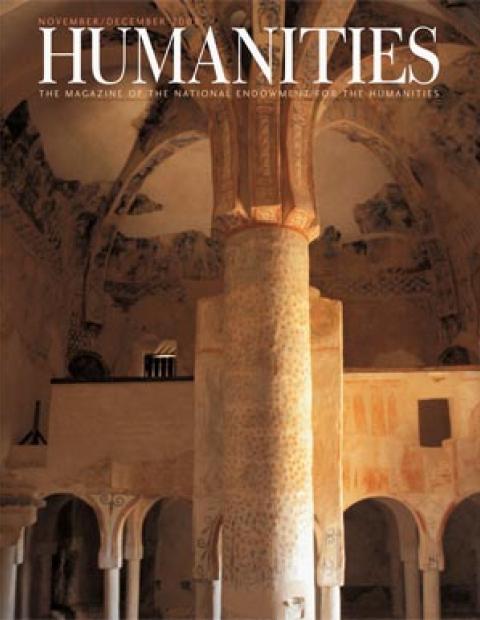

One of the great pleasures of my own work is reading NEH-funded research like that in The Arts of Intimacy, an ambitious and handsome study of art and architecture on the Iberian Peninsula prior to Christian rule. As Muslim rule began, in the eleventh century, to slowly give way to Christian rule, instability followed, along with a series of stunning battles and assassinations. Yet from this chaos emerged an unrivaled period of Arabic love poetry, described in this issue’s cover story, “Thieves of Pleasure.” Steal a few moments from your busy workload and enjoy.