Edgar Allan Poe should have become a lawyer. A brilliant, inventive mind with an eye for detail, Poe could have spotted the need for copyright protections, the absence of which made it difficult for him to prosper as a writer. The alternative would have had other benefits as well. It would have been acceptable to his foster father, as law was an appropriate profession for a Virginia gentleman, and it would have allowed Poe to manage the family import-export business in his spare time. Perhaps, also, the city of Richmond would today be honoring a favorite son with a statue, just down Monument Avenue from the one of General Lee, with the inscription “Edgar Allan Poe, fortunate son of Virginia, graduate of the University, and creator of the international legal system that endures to this day.” Edgar Allan Poe, Esq. probably would thus be memorialized in stone, just as the actual Mr. Edgar Allan Poe, writer, is not.

But as the Roman statesman Cato the Elder so sagely commented: “I would much rather have men ask why I have no statue, than why I have one.”

In Poe’s case, it’s fair to ask why. Fortunately, for inquiring minds, the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond provides the necessary information to make the query. Located in the Old Stone House, built in the eighteenth century, the museum includes a series of exhibits on Poe’s life and his enduring relationship with the American public.

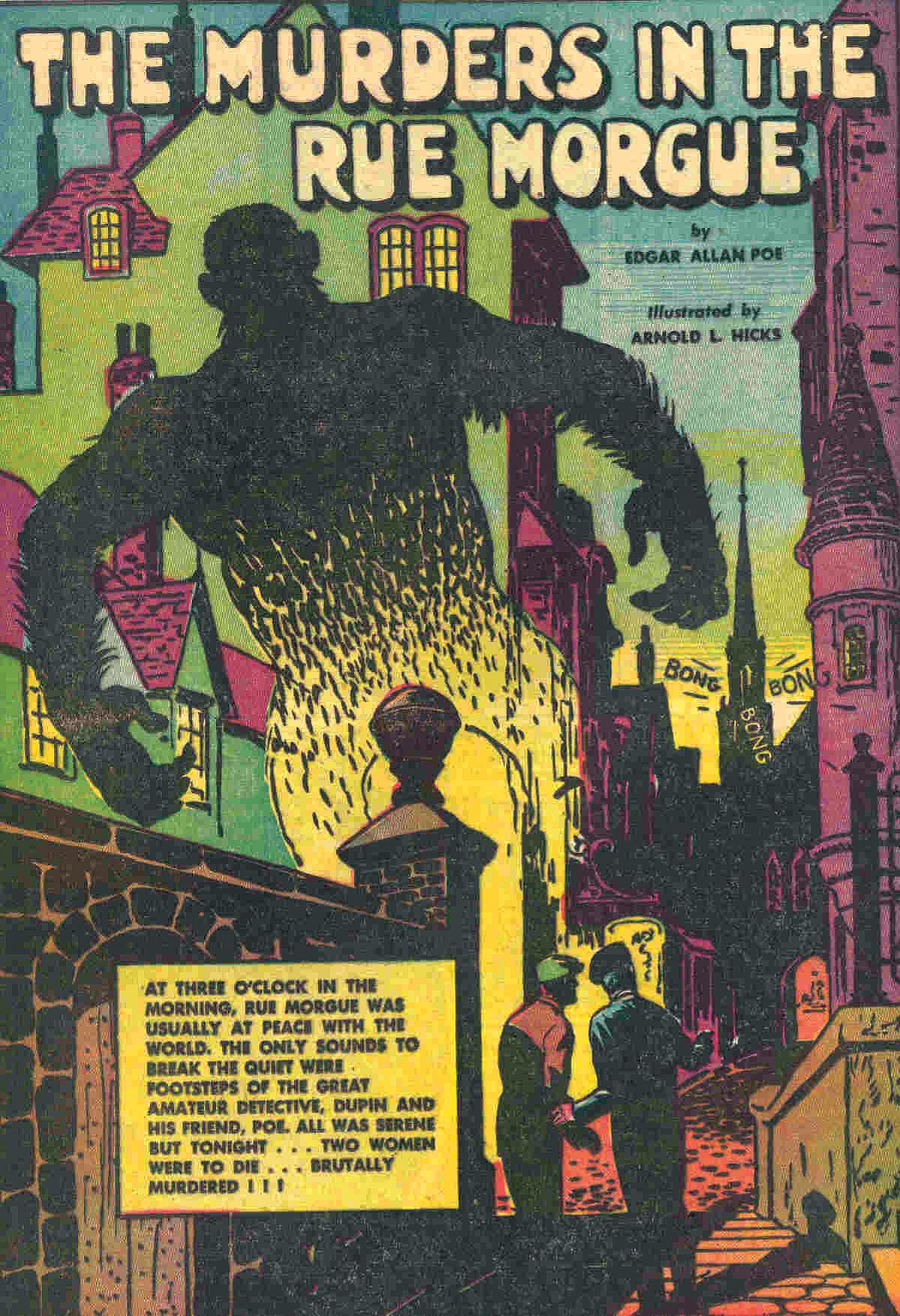

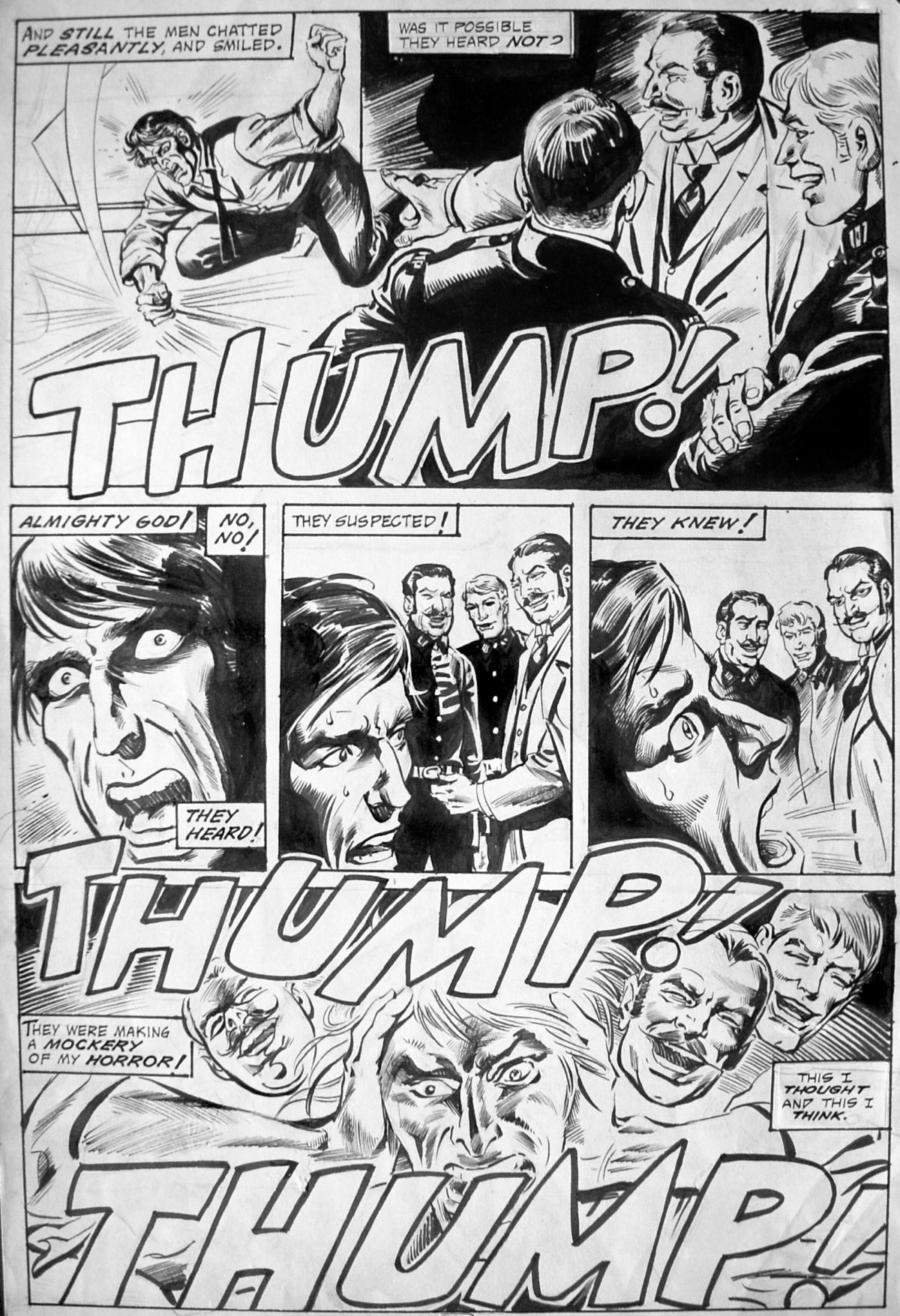

More than any other writer from the literary canon, Poe remains a formidable figure in other media. At the inception of the motion picture, D. W. Griffith made a short, silent film on the life of Poe—one of his first. Today, Poe Museum curator Chris Semtner notes that Ridley Scott is rumored to be planning an adaptation of the short story “The Tell-Tale Heart,” while Sylvester Stallone plans to direct a biopic. Poe’s work has appeared in satire as well—The Simpsons includes numerous references to Poe, including a segment with a reading of “The Raven” (Poe was credited as a writer), and the themed comic “The Cask of Amontilla-D’oh.” In addition to film and television, Poe appears in written media, particularly comics and graphic novels. An exhibit at the Poe Museum, “The Incredible Mr. Poe,” documents this phenomenon. Not only are Poe’s works the subject of illustrated adaptation; Poe himself appears as a character in some as well: helping the Atom (“the world’s smallest super-hero”) defeat a gang of Baltimore criminals, and giving a time-traveling Batman advice on how to clean up the streets of Gotham City. Semtner notes that the exhibit, which was partly funded by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, has elicited an unusual public response. Fans of Poe have sent the museum many additional comic books with direct examples or hints of Poe’s influence.

How, and why, does Poe continue to be a major figure in cartoons, comic books, and other forums normally foreign to major authors? It is hard to imagine Dickens, Melville, or Hemingway as characters in comic books. What makes Poe different? “He’s just somebody immediately recognizable, and he’s this legendary figure, sort of like the nineteenth-century James Dean,” says Semtner. It’s an apt comparison, as Poe’s role as a popular journalist necessitated a public presence. One of the first writers to support himself solely through writing—a novel concept—Poe had to appear in the public eye to pay for his living expenses. Although his writings might suggest the author was an occult-obsessed recluse with a taste for the macabre (or worse), Poe was no social outcast. An immaculate dresser, he was frequently out and about. He had a fondness for women, one that was reciprocated. As a teenager, Poe wrote love letters to young women at his sister’s school and developed a wildly passionate following—only to lose it when the amorous schoolgirls discovered their erstwhile suitor had written them all the same letter.

Poe’s penchant for trickery continued throughout his professional life, and he became a master of publicity stunts. While in New York, he published a piece in the New York Sun that related the account of an adventurer who crossed the Atlantic in a hot air balloon, then landed in Charleston. Many in New York, gripped by the account, purchased subsequent editions of the Sun, only to be outraged when they realized the news was a hoax: Poe had purposefully placed the landing in Charleston, knowing it would take a few days for the truth to reach New York.

An astute marketer, Poe included elements of his fictional work in his periodical writing. After a short essay on “secret writing” garnered public attention, Poe incorporated ciphers into “The Gold Bug.” To promote cryptography, which lent itself to Poe’s interest in mysteries and detective stories, he placed a notice of his proficiency in solving coded writing in a Philadelphia paper. Readers sent him encoded messages, which he publicly solved. In fact, Poe solved almost all the writings sent to him, prompting some to suggest that he “sent himself some of those cryptograms,” says Semtner. Regardless, Poe succeeded in creating a popular interest in cryptography, which might have increased demand for his books.

By drawing attention to himself, Poe drew attention to his literary efforts, but this did not result in great wealth. Publishers, due to a lack of copyright law, were free to reproduce whatever works they wanted, and writers were paid a pittance as a consequence. Poe was famous and his works were widely read, but there was something else at work in his publicity-seeking, a murkier side to all this theatricality. Unlike Dean, Poe was a rebel with a cause: exploring the sometimes unpleasant aspects of human emotion.

Along with Hawthorne and Melville, Poe was a pioneer of dark romanticism. Opposing the transcendental thinking of Emerson, dark romantics held less optimistic views on mankind, nature, and divinity. Man was not perfectible, but instead prone to sin and self-destruction. Morality was certainly possible, but man possessed no inherent divinity or wisdom. Nature was also an ambiguous force—dark, decaying, and destructive. As products of nature, man possessed this dark taint, and it constantly battled with, and frequently overcame, Lincoln’s “better angels of our nature.”

Uplifting stuff. These topics, however, articulated a truth several nineteenth-century thinkers refused to address: The regimented, mechanical, and impersonal ethos of the industrial age stifled what it meant to be human. Poe reacted by attempting to draw out from his readers feeling, intuition, and imagination. In the “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” the first detective story ever written, one can feel the trepidation and excitement of C. Auguste Dupin as he wanders the winding streets of Paris in the dead of the night. Poe knew man’s inner conflict better than most, and expressed it fifty years before Freud bought his first couch.

This exploration of emotion is what makes Poe’s work so compelling, even today. Poe speaks to the underlying tension of the human heart in an accessible way that makes people want to read him. It is no accident that he was featured in a Batman comic—Batman is Poe’s superhero. Inhabiting a rotting, gothic, and corrupt city, Batman is tormented by his own vengefulness and rage, and frequently he resorts to the brutality of the criminals he seeks to destroy. Emotional complexity gives characters a richness and depth that a transcendental superhero like Superman lacks. In the gleaming, technological, and seemingly perfectible world of our time, Poe reminds us of our darker impulses, fallibility, and ultimately, humanity.