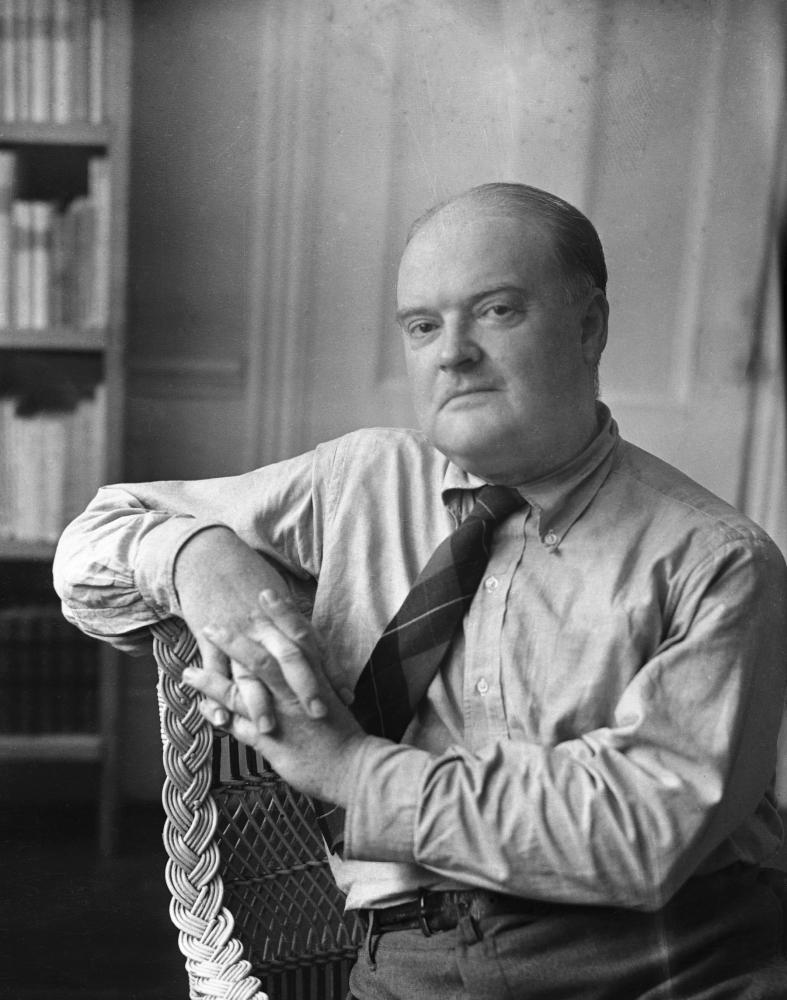

By the end of his life—hell, by the middle of his life, Edmund Wilson was a fat, ferocious man: petty, pretentious, and petulant, a failure at many of the most ordinary tasks of life. But, man, could he dance: through a poem, through a book, through a library. He was the Nijinsky, the Nureyev, at what he did—a genius, really: probably the greatest reader America has ever known.

Do his own works still have an audience? Axel’s Castle, for instance, that astonishing first collection of literary essays he published in 1931? Or To the Finland Station, his 1940 analysis of the intellectual roots of socialism? Or Patriotic Gore, his 1962 study of the literature of the American Civil War? With two volumes of his essays and reviews in print from the canonizing Library of America, you’d think the answer must be yes. And yet, to read Edmund Wilson today is to get the impression that he belongs to some lost epoch—a day further gone than the real distance that separates us from his style of writing.

As a matter of history, his place is clear enough, I suppose. From the mid-1920s to the early 1960s, Wilson was the premier literary critic in America. As an editor at Vanity Fair in the 1920s, then at the New Republic, and writing all the while for the New Yorker, he defined the life of arts and letters in the United States, publishing volume after volume of selected essays and reviews.

That’s not to say he was the most influential figure of his time. During Wilson’s life, the followers of Marx and Freud changed literature far more than he did—which makes sense, if you think about it: Literary theorists, people with a system, make reading and writing easy; that’s why they gain such importance. Edmund Wilson could never begin to create that kind of system. His unique success came from his unique genius. Even he couldn’t teach someone else to do what he did: absorbing books and making intelligent points about them.

Sometimes he got it wrong. His prose was merely good enough—not sparkling; only clear and well organized—and he got nosebleeds whenever he tried to follow philosophy up into the stratosphere of metaphysics. For that matter, he never understood escapism, and so, in a golden age of Hollywood screwball fluff, he condemned American movies as inferior to European—to say nothing of his famous essay that thundered against mystery novels: “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?”

Mostly, though, he got it right. And if he seems lost to us now, that’s not just because we have no similar genius to occupy the space that he filled. It’s also because that space has nearly disappeared. The magisterial critic has no role left in America, really. We appreciate, we enjoy, we peruse, we watch. But we don’t define ourselves by reading anymore. The novel, the premiere art form of western civilization over the last two hundred years, has ceased to be the mark of civilization. And so what need have we of Edmund Wilson—that fat, ferocious man, so nimble on his feet?

Born in New Jersey in 1895, Wilson was a product of as elite an education as the nation offered at the time. He started out at The Hill prep school, then went on to Princeton, from which he graduated in 1916—having formed, with his classmate F. Scott Fitzgerald, one of the most consequential literary friendships in the history of American letters. Early in his career as a writer, Wilson set out to carry on, in the words of his biographer Lewis Dabney, “H. L. Mencken’s work of making prudery and naïveté unfashionable.”

Seeking that end, he read his way across the spectrum of modern writers: Proust, Joyce, Eliot, and Valéry; Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Lermontov, and Pushkin, together with almost all the twentieth-century American writers. Along the way, he indulged his other great passion—for women. Several of his affairs ended up in marriage, the most famous being his wedding to Mary McCarthy, a woman seventeen years his junior.

McCarthy, in the words of one of her friends, had “wonderful gray eyes—searching eyes.” She was a sexual creature for whom “sex and love and social conquest were,” as she wrote, “inseparably wedded in my mind with men.” Her passion for sex equaled that of Wilson’s, who in his journals gives us literary versions of their sexual encounters. But there was also a deep intellectual connection between the two. As Wilson remarks in his journal of the time (published as The Fifties), “Mary had an uncanny instinct for knowing how my mind was likely to work; she established, in a peculiar way, very close intellectual and what may be called sensibility relationships—as when we used to have dreams that paralleled one another’s.”

In the end, the age gap between Wilson and McCarthy—together with their drinking and infidelities—doomed the marriage. Meanwhile, of all his mistresses, there was only one, Frances Minihan, who was more than just a sexual affair. Wilson met her in 1927. The affair was long lasting and seems to have been the opposite of his marriage with McCarthy. Frances was a poor woman from Brooklyn, and despite his mental attempt at class-leveling, Wilson never intended to marry her. He did, however, keep coming back to her, both for sex and for conversation, which sometimes took the form of a confession.

Like everything in Wilson’s life, the affair became a subject of literary exercise. Frances, who appears as a character in his novel, Memoirs of Hecate County, fascinated Wilson sexually. “Her pale little passionate face in the half light with mouth moist, and always ready, more like a sexual organ than a mouth, felt the tongue plunging into it almost like intercourse.” In many ways (as Dabney notes), what Wilson did in writing about sex with Frances in that novel was to break the American taboo against describing sexual acts precisely—which led to the book being banned in some places when it first appeared.

Still, it wasn’t as an artist himself that Edmund Wilson gained fame. His position as the nation’s chief critic and literary arbiter derived from his persistent attempt to promote a genuine artistic culture. In “Talking United States,” for instance—an article Wilson wrote about Mencken’s The American Language—he argued that American English offered real advantages to the writer, for it had grown beyond its British origins by incorporating the foreign elements brought to America by immigrants.

No, the problem for art wasn’t the American language. It was the American culture. Wilson was typical of his time in condemning the commercial aspect of life in the United States as an obstacle to creating anything of artistic value. The country, he wrote, is “simply not built” for artists, and so he urged Americans in search of culture to head to the Mecca of Paris and “drink it from the source.”

USSR in Construction, which presented an idealized version of the future society. Even such staunch anti-communists as Sidney Hook were mesmerized, he wrote, “by the pictures of tractors and power dams.”

But when he went to Russia, Wilson quickly realized that the Soviet Union was far from being a classless society, and Stalin, as he described him in To the Finland Station, was a terrifying barbarian. What Russia had represented to the young Wilson was the possibility of a literary culture—and so, when T. S. Eliot remarked, in defending the study of the ancients against the younger Russian literature, that “half a dozen great [Russian] novelists do not make a culture,” Wilson went to its vehement defense. As a literary critic, and someone who read the Russian language, Wilson knew that in contrast to “half a dozen” of Russian writers, America could not boast itself of having an equally potent dozen of its own.

Wilson’s visit to Russia made him understand what few Westerners did at the time. Pushkin created the Russian literary imagination and literary culture which, as Wilson explains in his essay “In Honor of Pushkin,” permeated Russian life through the novels. When he saw the Russian mise en scène of Pushkin’s The Queen of Spades, and people talking about it for hours over vodka, he had the feeling of being in a world that he could not find in his native country. After he left the theater, he wandered the streets of Leningrad, where people could not stop “talking and drinking.” It was as if these streets were peopled by “the characters of Dostoyevsky, uneasy, unable to relax in sleep,” and thus they roamed “the bridges in the half-day of night: the dissipated, the lonely, the thoughtful, the poor.”

After seeing Shakespeare and Chekhov performed on the Russian stage, Wilson was mesmerized. Even foreign classics in his assessment were of higher quality. In “The Classics on the Soviet Stage” he wrote about Shakespeare: “When I compared this Soviet production, with its seriousness, its large scope and its elaborate attention to detail, with a production of Romeo and Juliet which I have seen in New York last winter [1934], it must be admitted that the Soviets had still very much the best of it.” Later, in 1947, in his book Europe without Baedeker, he wrote: "The London theater, to a New Yorker, is amazing. It used to be very much less interesting than ours, but it is at present incomparably better. Our stage has been demoralized by Hollywood. . . . Londoners—again, like the Russians—have needed the theater for gaiety, for color.”

Those wonderful performances would soon come to an end, destroyed by the new Stalinist restrictions. Wilson never had any illusions about Stalin, and he understood—as most of his literary contemporaries did not—that Marxism was sterile as an interpretative tool. He wanted it to be culturally powerful, however, and, for the young Wilson, if the Soviet regime went wrong, that must be because of Stalin’s barbarism and lack of literary culture. “If Marx and Engels and Lenin and Trotsky are worth listening to on the subject of books, it is not merely because they created Marxism, but also because they were capable of literary appreciation.” Trotsky, for instance, “published in 1924 a most remarkable little study called Literature and Revolution,” which understood how, under the tsars, “imaginative literature in Russia played a role which was probably different from any role it had ever played in the life of any other nation.”

The explanation, in Wilson’s eyes, was what he calls the “art of implication,” which developed as a result of censorship: “Political and social criticism, pursued and driven underground by the censorship, was forced to incorporate itself in the dramatic imaginary of fiction. This was certainly one of the principal reasons for the greatness during the nineteenth century of the Russian theater and novel.”

And yet, Wilson’s real breakthrough, beyond the other critics of his time, came because he refused to simplify reading. The condemnation of Marxism as sterile for its “simplicity of vision” extends far beyond Marxism. It is, in Wilson’s writing, a weapon against all the ways in which a literary vision can be compromised by political messages or propaganda. For this reason, he rightly declared, Balzac “is worth a thousand of Zola.”

Long before his death in 1972, much of his life had turned into farce. From 1946 to 1955, for example, he didn’t pay his income tax—almost certainly from procrastination and financial incompetence, though in 1963 he published an unreadable volume called The Cold War and the Income Tax: A Protest that purported to find a high moral justification for it all.

By that point, however, the ground was shifting under his feet—or, rather, what had looked to the young critic in the 1920s as a vast plain of American letters was narrowing to a small ledge, and even someone as surefooted as Edmund Wilson was having trouble keeping his balance. What role was there, once we reached the 1960s, for a master reader of American literature? Lionel Trilling, Leslie Fiedler, Dwight Macdonald—all the great American literary critics of the time found their options and their importance dwindling.

Some of them went mad as a consequence—Dwight Macdonald racing up to the student riots at Columbia University in 1968, for example, to embrace the “youth culture” as the great new hope for America. Others settled back into curmudgeonly grumpiness. Others simply became irrelevant.

Perhaps that’s the best way to describe Edmund Wilson. However well he wrote, however well he performed the cultural hygiene of criticism, he seems astoundingly irrelevant now. Who reads him these days? Who, for that matter, reads the artists he worked to make central to the American experience? When was the last time you picked up a book by Upton Sinclair or John Dos Passos? When were Sinclair Lewis and Theodore Dreiser last passionately pursued by readers? Who even knows the name of Floyd Dell?

The culture that wanted to flourish from the twenties through the fifties faded away from the 1960s down to our own time, and we have no space left for a critic like Wilson to fill. The great reader—that fat, ferocious man, dancing through books—is astonishingly irrelevant now. The loss is not Edmund Wilson’s. It’s ours.