From the soldiers who saved Europe's artistic treasures to a California farmer who redefined ancient warfare, this class of National Humanities Medalists reflects a variety of contributions to the humanities. The group also includes a Cold War historian, a curator, a philanthropist, an education advocate, an archivist, a literary scholar, and two authors. They were all honored this past November at the White House.

Stephen H. Balch

FOR ACADEMIC FREEDOM

Stephen H. Balch was a professor at John Jay College in New York City when he noticed something big happening to American higher education. A certain dispiritedness had taken hold, and it was growing. Colleges and universities across the country seemed to be losing their sense of purpose. This change was affecting the curriculum too, or perhaps the changing curriculum was its source. With the increase of specialization and the rise of political correctness, fewer schools were addressing the broad range of human achievement whose rough contours had once defined a college education.

Balch was happy where he was, teaching John Jay’s unique mix of traditional undergraduates and New York City policemen fulfilling their credit requirements. But, in 1987, he left the classroom to found the National Association of Scholars (NAS), a membership organization for university and college faculty that seeks to strengthen teaching and research in the humanities and social sciences. NAS has worked to rekindle the sense of wonder that Balch, who serves as the organization’s president, felt was vanishing from America’s colleges and universities.

Over the last twenty years, NAS has grown into an important voice in debates over intellectual diversity, politicization, and freedom of expression on campus. Through Balch and other spokesmen, and through research reports and the quarterly journal Academic Questions, NAS has become a major source for information and ideas in the effort to promote reasoned debate and academic pluralism.

“Balch rallied the forces of those opposed to political correctness in the universities,” says Harvard professor of government and 2007 Jefferson Lecturer Harvey C. Mansfield. “He didn’t just take a stand, he organized a stand in favor of academic standards. He’s tried to restore the impartiality of American universities, and he has succeeded in making this effort powerful and visible, if not always successful.”

In 1999, Balch coauthored a major study on the changing nature of literature studies. “Losing the Big Picture: The Fragmentation of the English Major Since 1964” examined course catalogs to report a diminishing emphasis among English departments on classic authors and texts and an increasing preference for the trendy and obscure. This was a follow-up to another important report cowritten by Balch, “The Dissolution of General Education: 1914–1993,” which documented the purging of many survey courses in the humanities, social sciences, and the sciences from graduation requirements at colleges and universities nationwide.

In addition to raising alarms, Balch and NAS have done a lot of quiet work too, especially in the area of programming reform. To rebuild some of the intellectual heritage that has been dismantled in recent decades, NAS has pioneered the concept of creating academic programming to champion the study of Western civilization and free institutions. The organization has provided intellectual and logistical support to professors who so far have established twenty-five such academic centers.

NAS has acted as an incubator for other reform organizations. In addition to its forty-six state affiliates, NAS helped bring about the creation of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni and the American Academy for Liberal Education. ACT works with trustees, alumni, and donors to support many of the same goals NAS itself pursues: liberal arts education, high standards, and intellectual freedom on campus. AALE, an accrediting agency that emphasizes high-quality general education at the university level, has distinguished itself by conditioning accreditation not simply on the organizational or financial integrity of academic institutions, but on the quality of their curricula.

Balch was born in New York City and grew up in Brooklyn. He received a bachelor’s in political science from Brooklyn College. At the University of California, Berkeley, he earned a master’s and, in 1972, a PhD in political science. After a couple of years of teaching on the West Coast, he returned to New York, where he took a job at the CUNY Graduate Center before being hired in 1974 by John Jay College.

The institution he passed through that best expressed his academic ideals, however, was Brooklyn College. It was not, he says, a perfect education, nor would it be a model education for everyone, but it had one very desirable characteristic: “It was serious.”

Balch served as chairman of the New Jersey State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights from 1985–1990, and was a member of the Committee from 1990 to 2005. He was also a member of the National Advisory Board of the U.S. Department of Education’s Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education from 2001 to 2004.

The animating spirit of his work, Balch says, is to “revive intellectual pluralism on campus” and “bring back a philosophic sensibility that has become too rare.”

—David Skinner

Russell Freedman

MAKING HISTORY LIVE

Children’s nonfiction author Russell Freedman says writing for children is no different from writing for adults. “I write for anyone who can read . . . up to senility. A good book for kids is also a good book for their parents and grandparents. If my grown-up friends cannot read one of my books with interest and respect, then it’s not a good book for kids.”

That rule, combined with a childlike curiosity, has guided Freedman’s career, which spans more than fifty years and fifty books, including the Newbery Medal-winning Lincoln: A Photobiography, and Newbery Honor Books on the Wright Brothers, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Marian Anderson.

As a boy, Freedman was immersed in writing. His father, the West Coast manager of the Macmillan publishing company, would host dinner guests such as John Steinbeck and Margaret Mitchell, and the house brimmed with books and book talk. His own copy of Treasure Island shared shelf space with his father’s collection of signed first editions. “Being a voracious and promiscuous reader,” he says, was “just a normal part of life.”

Freedman went to Berkeley in the early Fifties, “a rather repressive time,” he says—a time when Berkeley professors were made to sign loyalty oaths. “I got a job stocking the shelves at Montgomery Ward, and I had to sign a loyalty oath in order to do that.” His indignation led him to protest and would later inspire In Defense of Liberty: The Story of America’s Bill of Rights.

He always knew he wanted to be a nonfiction writer, but he fell into children’s writing almost by accident. When working as a reporter for the Associated Press, he came across a newspaper article about the invention of a Braille typewriter by a fifteen-year-old boy. It became the inspiration for his first book, Teenagers Who Made History in 1961. “Because of its subject,” Freedman says, “the publisher was interested in marketing it as a book for young readers. So that was nothing I had really planned.”

Freedman calls his 2003 In Defense of Liberty his greatest personal success. “What is more important than the Bill of Rights to America?” he asks. “Nothing! And I got to try to convey this information to a new generation.” It was also his biggest challenge, he says: “You’re dealing with legalisms, to some extent, and abstractions, and you have to put them into human terms.”

He works a similar transformation in Lincoln: A Photobiography. “The Lincoln that I grew up with was a paragon,” Freedman says. “And the Lincoln I discovered when I was working on the book was a person who had trouble making decisions, who was prone to fits of depression, and who had a capacity for change that is quite admirable and quite fascinating to watch develop.”

Freedman’s work is distinguished as much by its writing as by its meticulous integration of words and images. He does his own photo research, and pairs pictures with paragraphs until they are “tightly knit together.” “Every photo I pick is key to a paragraph in my manuscript,” he says. “It’s like a kind of counterpoint. A good picture should say something that the text doesn’t say, and the text should say something that isn’t evident in the photo.”

He has described his research technique as going “back in time through bibliography,” starting with the most recent scholarship and moving toward primary sources. Keeping up with the latest sources is important because “you’re writing to people who are living now, and who are living in a culture that’s very different from the culture that existed when Carl Sandburg wrote about Lincoln.”

Freedman says history education in the United States is failing. He complains of bland textbooks written by committees and says that history should be written with “a point of view.” He wants students to be reading history “that has a cutting edge, that deals with real values and real controversy, and for that reason can engage the reader’s interest and maybe even the reader’s passions.”

—Daniel Scheuerman

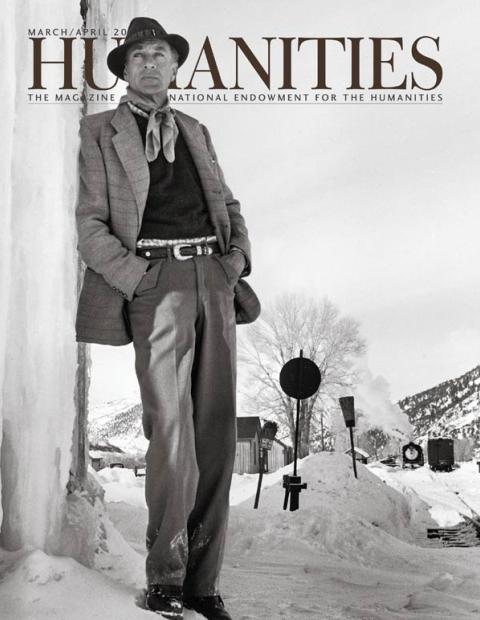

Victor Davis Hanson

THE FARMER-CLASSICIST

Victor Davis Hanson, one of America’s best known and most prolific historians, grew up on a farm in Selma, California. His parents—a school administrator and one of California’s first female judges—made sure that he and his bothers worked hard. “If they saw you sitting around, they’d ask, ‘What are you doing?’” Hanson still labors with that question in his ear.

What unites his work—farming, scholarship, teaching, journalism—he also learned on the farm. “I see my whole career as integrated. I grew up on a farm and inherited a tragic view from my parents and grandparents. Studying the classics for eight years, both here and abroad, and teaching them for twenty years, all reiterated the sense that human nature was unchanging and the human ordeal predictable. Whether it was working on a farm or reading Sophocles or Thucydides, the message kept being reiterated in different ways: Nothing really changes.”

Born in 1953, Hanson intended to be a lawyer, but at the University of California, Santa Cruz, he gravitated to the classics. He received a doctoral fellowship to Stanford and then spent two years in the late 1970s doing research in Athens. After he earned his PhD, though, he “realized that there wasn’t a lot of work for a classicist.” Also, his grandfather had passed away, so, he says, “I just went back and worked on the farm.”

Hanson’s scholarship, though, had already yielded a fundamental insight into life in ancient Greece. An Italian classicist, Emilio Gabba, had read his dissertation and arranged for its publication. “I was out on a tractor and my wife told me, ‘Some guy is on the phone and wants to publish your thesis.’ He wanted $2,000 to cover the costs, and I told him to forget it. Later they waived the fee, and that’s how Warfare and Agriculture in Classical Greece got published.”

Classicists had assumed that war in the Greek city-states brought on famine as ancient armies systematically destroyed orchards and vineyards. Hanson knew the backbreaking work required to uproot vineyards and fell trees. He questioned what was possible with primitive tools. “I tried to put myself in their place, to emphasize the physical ordeal of life in the ancient world.” His dissertation—and its follow-ups The Western Way of War, 1989, and The Other Greeks, 1995,—began a complete reinterpretation of war in classical Greece.

“Hanson’s work on the role of the small family farmer in the development of democracy is the most important work in Greek history in my lifetime,” notes Yale University classicist and NEH Jefferson lecturer Donald Kagan. “Nobody told that story before Hanson, and its significance is hard to exaggerate.”

When the price of raisins declined by two-thirds in the early 1980s, Hanson found himself needing work. He drove over to the nearest school, Cal State Fresno, and offered his services. He started teaching Latin classes and ended up founding a department.

“CSU Fresno has a high number of minority students and poor kids,” he says. “We had to make the argument to a Hispanic kid that he should invest a thousand hours a year in Greek when he nevertheless had student loans to pay and a job to work, and when his family couldn’t see any correlation between reading Aeschylus and success. But the basic skills one needs to be successful in society are not always vocational. You will succeed or fail by the degree to which you reason, speak, and write well. The Greeks give us a blueprint for such mastery. The mechanics of classics are practical; they will improve your knowledge in every discipline.”

Hanson continued writing too. He wrote books about the classics, farming, immigration, but most particularly about war. “The Western Way of War sold very well, and my agent convinced me that was the way to go rather than more essays on agricultural life.” Carnage and Culture, published in 2001, examined nine battles from Salamis to Tet and tried to understand why Western armies had emerged victorious in each. It became a best seller in the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks, turning a classics professor into a much-sought-after public commentator on war and politics. He retired from CSU Fresno in 2004, and today he writes regular columns, essays, and even a blog.

Hanson is not sanguine about our culture. “I don’t see enough people standing up to defend the West. We don’t realize how tenuous its legacy is and how it has to be transmitted from generation to generation. The nature of man doesn’t change, and that’s reassuring, since we know the necessary conditions that can save him from himself. The legacy of the West is a guidance system through the natural perils of human nature and behavior.”

—Robert Messenger

Roger Hertog

FINANCING THE HUMANITIES

He is not a writer, a scholar, or a curator. Yet Roger Hertog, a retired sixty-six-year-old businessman, works to fund and otherwise support many a writer, scholar, and curator. He is a benefactor, one with an enormous appetite for ideas. Modesty, however, may be his stock in trade. “It’s not like I’m some great public intellectual,” he says.

He is chairman and part owner of the New York Sun, the first new daily newspaper to enter the fray of that city’s highly competitive market in a long time, chairman of the New-York Historical Society, a former chairman of the Manhattan Institute, a board member of the New York Public Library, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the New York Philharmonic. He is on the board of Commentary magazine, and is a current board member of the American Enterprise Institute, where he has endowed a fellowship currently held by the eminent bioethicist Leon Kass. It is through these and other institutions, he says, like the Shalem Center, a think tank Hertog helped found in Israel, that he’s made his contribution to the humanities, practicing what he calls “strategic philanthropy.”

Hertog’s parents were Jews who fled Germany under Hitler. They both arrived, separately, in the United States in 1938. Hertog grew up in the Bronx. “Like most Jewish families, we had not one but two pictures of FDR in our house.” He satisfied his precocious interest in newspapers at a small public library near University Avenue.

As a teenager, his school-bred love of history turned his thoughts to questions inspired by his own family’s past. Why, for instance, didn’t he have grandparents?

He began by reading about Roosevelt, which led to reading about Churchill, which led to reading about Stalin and Hitler. Soon he was asking about the Western response to Nazism, giving rise to a lifelong preoccupation with Jewish issues. He says, “Growing up a German Jew you were really forced to ask yourself the deepest questions.”

Still, Hertog says, “there were two driving interests for me as a young man.” The first was to make enough money to live on his own. The other, he adds, was girls. He went to City College at night and worked during the day. His first job was at “a young aspiring company” called Oppenheimer and Company, which has grown into a major player in the financial world. His next job was at Sanford Bernstein. Bernstein, the company’s founder, whom Hertog calls a “very inspired, controversial, difficult, but enormously creative person,” became for him a model of how to live and contribute to one’s community and society at large.

Hertog first became interested in public debate as practiced by think tanks and journals of opinion in the sixties. He was an avid reader of two “small-circulation magazines that had a disproportionate impact” on American government and society: Commentarymagazine, then edited by Norman Podhoretz, and The Public Interest, the recently defunct policy journal founded by Irving Kristol and Daniel Bell in 1965.

Reading an essay in The Public Interest, he says, was like reading a book, “but I didn’t have to read five hundred pages and there weren’t a billion footnotes.” The young financial analyst was slowly becoming a student of a different kind of market: the market of opinion.

Hertog says that on the one hand you have newspapers, which are ideas being sold at “retail.” The other extreme is books. “In between are think tanks and magazines.” It is no accident that Hertog is an important supporter of the Manhattan Institute and its signature publication, City Journal, which have been credited with inspiring many of the ideas that have transformed New York City in the last fifteen years.

Although his interests seem to range from politics to culture, “Jewish continuity,” he says, is the leitmotif running through all of his work.

The next big thing for Hertog, he says, is the American academy, which he’d like to see transformed by philanthropy. Hearing him joke about his private life, however, makes one think that Hertog might combine this interest in the academy with his interest in Jewish tradition by endowing a university chair in Jewish Humor. After mentioning that he’s been married for forty-two years, he lets fly an old-fashioned one-liner, “Orthodox Jews, Roman Catholics, and pigeons are the only ones who mate for life.”

—David Skinner

Monuments Men

SOLDIERS FOR ART

Long before World War II began, Hitler had planned the systematic looting of Europe’s finest museums and private collections. Thanks, in large part, to the Monuments Men, he wasn’t entirely successful. This group of 345 men and women, who were mostly American but who hailed from thirteen countries, applied their civilian talents as museum directors, curators, art historians, archaeologists, architects and educators to save, quite literally, Western civilization’s treasures.

In advance of the Nazis, the Monuments Men evacuated 400,000 works from the Louvre, including the Mona Lisa, which they shuttled to safety six times. Just ahead of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, they emptied and stashed more than two million works from the Hermitage.

But it wasn’t only Nazi plunder they had to guard against. It was left to the Monuments Men to figure a way to save da Vinci’s Last Supper, painted on the refectory wall of the convent at Santa Maria delle Grazie, before the Allies bombed Milan. By jury-rigging a scaffold of steel bars and sandbags around the wall, they saved the masterpiece. After the raid, it was the only wall in the refectory still standing. By using aerial photos, Monuments Men diverted Allied airmen away from many important sites, including the Chartres Cathedral; when a cultural site ended up an unintended target, Monuments Men rushed in to make repairs.

In March 1945, Allied forces discovered the first of Hitler’s many secret repositories of art, more than one thousand hiding places in all, stashed mostly in salt mines and castles. That’s when the Monuments Men began the serious task of conservation, restoration, and restitution. In all, they restored and returned to their rightful owners more than five million works of art, including works by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Botticelli, Manet, and many others, plus sculptures, tapestries, fine furnishings, books and manuscripts, scrolls, church bells, religious relics, and even the stained glass the Nazis had stolen from the windows of a cathedral. “This was the first time an army fought a war on the one hand and attempted to mitigate damage to cultural treasures at the same time,” says Robert Edsel.

Edsel has spent eleven years and more than three million dollars researching, piecing together, and championing the little-known story of the group referred to officially as the U.S. Army’s Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives section or, more commonly, the Monuments Men.

Iinspiration came to Edsel quite accidently. Barely forty at the time, he was in Europe, after selling his lucrative oil exploration business, to ponder his life’s next big adventure. He was standing on the Ponte Vecchio, the only one of Florence’s fabled bridges the Nazis hadn’t blown up during their 1944 retreat, when he began to wonder how, despite the war’s widespread destruction, so many paintings, sculptures, monuments, cathedrals, and museums had survived. Who, he asked himself, had saved it all?

Though he had little previous interest in art and no knowledge of the war itself beyond the stories his father, a Marine who had served in the Pacific, had told him, Edsel made answering the question his personal calling.

Edsel has detailed the Monuments Men bravery and resourcefulness in an abundantly illustrated book, Rescuing Da Vinci: Hitler and the Nazis Stole Europe’s Great Art—America and Her Allies Recovered It, 2006. He also coproduced The Rape of Europa, an NEH-supported documentary focusing on the Monuments Men, and late last year he convinced Congress to pass a resolution honoring them. Recently he established the Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art, whose mission is “to preserve the legacy of the unprecedented and heroic work of the Monuments Men by raising public awareness of the importance of protecting and safeguarding civilization’s most important artistic and cultural treasures from armed conflict.”

Sixty-two years after the end of the war, only a dozen of the Monuments Men are known to be alive, the youngest, former sergeant Harry Ettlinger, now in his eighties. This puts Edsel, who believes there may be more still living, in a race against time. He has been ferreting out their details for the biographies posted on his Web site (www.monumentsmenfoundation.org)—so far he has collected 103—and personally meeting with the survivors.

Once their wartime duties were behind them, many of the Monuments Men went on to distinguish themselves in the arts, including Lincoln Kirstein, who founded the New York City Ballet; James Rorimer, who served as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Charles Parkhurst, chief curator of the National Gallery of Art. But, as the years passed, their wartime contributions sadly slipped from notice. As Edsel himself discovered, there was hardly a mention of the Monuments Men in all the vast literature of World War II. His unrelenting curiosity, energy, and deep admiration have brought honor to those heroes who saved Europe’s treasures. “Their search,” says Edsel, “was the greatest treasure hunt in history.”

—Rosanne Scott

Cynthia Ozick

TRUTH IN FICTION

“One test of the durability of fiction is whether it tells even a partial truth ten years after publication,” wrote Cynthia Ozick in 1983. Her novella The Shawl stands that test of time. Written in 1989 about a woman in a prison camp who tries to hide an infant in her shawl, the story continues to be taught in schools across the country alongside works by Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi.

Born in the Bronx in 1928 to a Russian Jewish couple, Ozick read widely early on. Her lyrical essay “A Drugstore in Winter” evokes those delicious hours when the traveling library would park near her parents’ pharmacy every two weeks. Among her favorite titles were the sumptuously illustrated children’s classics The Yellow Fairy Book and The Violet Fairy Book by Andrew Lang. Her love for books continued through school, and she recalls with affection the bookstores that lined Fourth Avenue: “There was this musty smell, and the owners ignored you completely and would become annoyed if you wanted to buy a book, because they were too busy reading.”

Ozick went on to the famously selective Hunter College High School in Manhattan, where, she says, “I got in by the skin of my teeth.” She thrived there. “But I have a sort of double vision of those, for me, happy times,” she says. “It coincided with our entry into the war and with its ending. I see it all now as through a veil of guilt.” The events of the Holocaust taking place at the same time would influence much of Ozick’s writing.

After earning a master’s degree from Ohio State, she returned to New York and threw herself into the writing life. Trust, published in 1966, announced a new voice in American fiction, one that conjured characters buoyed by narrative currents that, although probable, were never predictable. There followed The Pagan Rabbi and Other Stories, 1971, plumbing Jewish identity; Bloodshed and Three Novellas, 1976, examining being Jewish in an essentially pagan, Hellenistic world; Levitation: Five Fictions, 1982, introducing readers to Ruth Puttermesser, a major recurring character in Ozick’s works; The Messiah of Stockholm, 1987, telling the tale of a minor literary figure who believes he is the son of Bruno Schulz, the famed Jewish writer who was a victim of the Holocaust; The Shawl, 1989; and Heir to the Glimmering World, 2004, spinning a narration by Rose Meadows, who is fleeing failed love only to take up with a family fleeing their own upheavals. Ozick is considered a modern master of the short story, and her work has received the O. Henry Award four times.

Many critics regard The Puttermesser Papers as Ozick’s magnum opus. Novelist Carol Shields said, “This book, with its waves of rapturous invention, presents a saddened vision of the world that leaves the reader in a trance of happiness.” The book exposes the inner life of its protagonist, a New York intellectual who would rather read Plato than go out on a date, and who goes on to implement her utopian vision to make New York into a new Prague, where philosophy and art dominate the culture. How does a novelist create someone like Ruth Puttermesser? “I think my characters are there, and I have to wait for them to come,” says Ozick. “I think I dream them first. I don’t mean in sleep. It’s all so mysterious. I don’t think writers can be completely honest about where they get all their ideas.”

Ozick explains that her novella The Shawl wasn’t so much written as transcribed, as if taken down by dictation. “It was like an out-of-body feeling that I never had before and haven’t had since.” After its publication, a reader who was a psychiatrist contacted her because he believed Ozick was writing about her own experiences and wanted to help. “He thought I was writing autobiographically. He said he had had many patients who were survivors but who denied it. He insisted I was a survivor. The thing is I wasn’t there: If we all had five thousand years in our lifetimes, it wouldn’t be enough to absorb those events.”

Ozick is also an important critic. She won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism for Quarrel & Quandary in 2000. Her essays examine the origin of ideas: “Knowledge is not made out of knowledge,” she has written. “Knowledge swims up from invention—from ardor—and even an essay can invent, burn, guess, try out, dig up, hurtle forward, succumb to that flood of sign and nuance that adds up to intuition, disclosure, discovery.”

At age eighty, Ozick is not ready to stop writing. “You’re driven. It’s an urge,” she says. “I’ll probably continue writing til the day I die. I can’t give it up.”

“Not,” as one of her own characters would have it, “for all the china in Teaneck.”

—Steve Moyer

Richard Pipes

COLD WARRIOR

Richard Pipes has made a habit of being right, and about some of the biggest issues. He was right that the Russian Revolution was authoritarian in origin and nature, and he was right that the Soviet Union was a Potemkin state. His intellectual clarity is undeniable, as is the fact that his opinions have brought him as much opprobrium as praise throughout his career.

Pipes was born, in 1923, into a middle-class Jewish family in Poland. When the Germans invaded in 1939, his father immediately began preparing the family to emigrate. Using a forged consular document, they caught the first train out of German-occupied Warsaw and escaped to the United States by way of Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Once in America, Pipes sent penny postcards to dozens of colleges, explaining that he was a war refugee and needed “both a scholarship and assurance of gainful employment.” From four offers, he chose the small Ohio college Muskingum and got his introduction to American life. He tried to enlist in the fall of 1942, but as a foreign national he had to await the draft. In January 1943, he was inducted into the Army Air Corps.

Pipes was eventually sent to Cornell to study Russian, as part of his training to become an intelligence officer. During this period, he came across, in a local library, François Guizot’s History of the Civilization of Europe. “It showed me that all the things that I was interested in—notably philosophy and art—could be accommodated under the spacious roof of the discipline of history.”

Thus did his military service help determine the course of his life. “At the end of World War II, in which Russia’s role was decisive, there was immense interest in that country and very little knowledge of it, so I thought to devote myself to Russian history.”

Thanks to his wartime credits, Pipes was able to apply to graduate school while still in the army. In the fall of 1946, he arrived at Harvard, the institution he would make his home for his entire career. After receiving his doctorate—for a dissertation on Bolshevik nationality theory—he stayed on as an instructor and made his academic name with his 1954 book, The Formation of the Soviet Union: Communism and Nationalism, 1917–1923. As a historian, Pipes’s focus has been the intellectual roots of the Russian Revolution. He believes that his “greatest scholarly achievement is analyzing the Russian political tradition and demonstrating the continuity between tsarist Russia, Communist Russia, and Russia since 1991.” His magisterial two-volume history of the revolution, The Russian Revolution, 1990, and Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, 1994, presented the clear story of a coup d’etat by power-hungry revolutionaries whose goals, far from utopian, were purely authoritarian.

In the 1960s and 1970s, this view made Pipes a figure of great controversy. “I went against the current of prevailing opinion,” he told The Globe and Mail in 1996. “Whereas the profession as a whole regarded the Soviet Union as an essentially popular and stable regime, I saw it as an unpopular and weak regime.” He was attacked widely and repeatedly, but he never wavered in his convictions. Fellow historian Walter Laqueur characterized Pipes’s public stances as “courageous.” His response to Laqueur’s praise was characteristic: “If I was indeed ‘courageous’ in dealing with my critics, it is because I did not take them seriously.”

Soon enough, Pipes’s opinions were being regularly sought in Washington. In the mid-1970s, he chaired the famous “Team B,” a group of Russia and military experts called together to provide an alternative analysis to the CIA’s annual “National Intelligence Estimate” on the Soviet Union and to look closely into Soviet nuclear strategy. He served on the National Security Council in the early 1980s and closely advised Ronald Reagan on his aggressive stances toward Soviet Russia.

My main contribution,” he notes today, “was revealing the flaws in the détente policy and urging a policy designed to reform the Soviet political regime by a strategy of economic denial.” Pipes believes his government service also contributed to his scholarship. “My histories of the Russian Revolution gained a great deal from the opportunity I had had to observe at close range how high politics is made.”

Despite his work in Washington, Pipes never stayed away from Harvard for long and was always deep into a work of scholarship. “I emulated Anthony Trollope in that as soon as I finished one book, I proceeded immediately to the next.”

In his memoir of his life—Vixi, the title is Latin for “I have lived”—he noted that having defied Hitler he felt he had a “duty to lead a full and happy life.” And so he has.

—Robert Messenger

Pauline Schultz

A HISTORIAN OF PLACE

Pauline Schultz has spent most of her ninety-two years keeping the history of Salt Creek Oil Field in Midwest, Wyoming. The field is a nine-by-five-mile patch of land in what her father called “the beaten-est place.” In the 1920s, Salt Creek yielded one fifth of the petroleum produced in the country, and over the decades has provided work for millions of people.

In 1934, Schultz says, she “told everyone, ‘This field is important. Someday, we’ll have a museum.’” A self-described “history nut,” Shultz took notes and stashed memorabilia, and, in 1980, founded the Salt Creek Oil Field Museum. Its eclectic collection includes oil well maps her husband saved, thousands of photos, a 1924 doctor’s office, and The Midwest Reviews, which chronicle the activities of the oil field from 1920 to 1930.

As a curator, her favorite works are a collection of six-by-eight-foot photos of the early years of Salt Creek that were donated by Amoco when the company, a former owner of the field, reached its hundredth anniversary. “I wouldn’t take a million dollars for them,” says Shultz. On a personal level, she favors Early Days at Salt Creek and Teapot Dome, a book by Ed Bille, a friend who helped her with the museum.

The place Shultz has chosen to memorialize was not an easy place to live. “Dad used to say, ‘Why you can see farther and see less; have more cows and less butter; more sheep and less mutton, more gullies and less water than in ANY state in the Union!’”

What Wyoming does have is geologic good fortune. “Coal, oil, gas, uranium, all the wealth is underground,” says Schultz.

Her father, Charles Carl Miller, was born in Titusville, Pennsylvania, home of the nation’s first drilled oil well. His uncle taught him to drill, and the skill took Miller around the country. “His knowledge was in demand,” Schultz says. “In the field, Dad was known as ‘Crooked-hole Miller’ because he had learned the technique of how to correct the hole’s direction if the drill bit hit a rock, swerving to the side, going crookedly. He could pull the bit and straighten the drilling hole.”

“People traveled to the oil fields by the thousands when there was a boom. We would just pick up the pieces and go,” says Schultz, who crossed the Mississippi thirteen times before she was ten.

In 1924, her family moved to Midwest, a company town. Shultz estimates there were four thousand derricks there in the 1920s and 1930s. “It was the largest light-oil [meaning it could be used without being refined] field in the world. Oil gushed, sometimes as much as 160 feet high because no one knew how to shut off the wells.”

Her family moved on in 1927, but she returned in 1934 with her husband Walter Schultz, who went to work in the field. In their early years, he had to travel to the boosters, building-sized engines that “boost” oil through a pipeline. She went along, and together they lived in a sheep wagon outfitted for housekeeping. “It was the cutest little house in the world.”

It was a time when the companies owned the houses; you might not have had running water, and the work was hard. “You had to have endurance beyond imagination,” says Schultz, to work around the noxious smells or at temperatures twenty or thirty below zero when the water in the oil would freeze.

Ten to fifteen thousand people lived in Midwest and the surrounding camps when Shultz was a girl; now, she says, the population is fewer than five hundred. Twenty or thirty can do what five hundred people once did, says Shultz.

Visitors to the museum have included Lynne Cheney, whose grandfather arrived in Salt Creek in 1912; former senator Alan Simpson; and former Salt Creekers from as far away as Wales and Germany.

“Oh my lands, who would have thought that dignitaries, senators, coordinators, and other oil management people would wind up going through all my scrapbooks and albums. They would look intently at the huge maps that hung on the walls trying to visualize the outlying camps and four thousand derricks that had once stood,” Schultz writes in her memoirs. “The most heartwarming situations come when someone walks through the door and says, ‘Mrs. Schultz, you probably don’t remember me, but I know you.’ Upon hearing who they are, I jump up and hug them, and we embark down memory lane. Some I rocked when they were babies, and others’ great-grandparents had been my neighbors.”

Schultz retired in June and moved to Tennessee. Her life’s passion has been documented for the State Historical Archives in Cheyenne. For her thousands of hours of volunteer service to the museum and her community, she also has received a President’s Call to Service Award from the President’s Council on Service and Civic Participation.

Of her work, Schultz says, “I’ve loved every second of it.”

—Anna Maria Gillis

Henry Snyder

DIGITIZING THE PAST

After graduating from college at Berkeley in 1951, Henry Snyder worked for several years at a California department store, becoming the firm’s youngest buyer. At the same time, he served as an officer in the Army National Guard, where he built the Guard’s only full-strength rifle company in the western United States. Today, the scholar-administrator traces his knack for managing sprawling academic projects to both experiences. “Managing businesses, military units, large organizations—it’s all administration,” he says.

A specialist in British history, Snyder has been a professor and dean at the University of Kansas, Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge, and the University of California, Riverside. When he was appointed to head the North American part of the ESTC project in 1978, the initials stood for Eighteenth-Century Short-Title Catalogue—an ambitious effort to build a database of works printed in English-speaking countries from 1701 to 1800. Today, ESTC stands instead for the English Short-Title Catalogue, stretching from the early 1470s to 1800 to encompass the entire early printed period.

Supported by NEH, the ESTC includes hundreds of thousands of records from more than two thousand libraries on five continents—with more records still to be added. For Snyder, the project has required years of “proselytizing,” he says, since libraries use their own resources to supply the information. “I’ve visited hundreds of libraries and dozens of conferences and delivered many papers,” to encourage libraries to join the project. “I’m still doing it.”

By locating additional copies of early printed works, the ESTC provides better access for researchers. Snyder gives the example of an American scholar who might once have traveled to Scotland to study a rare book, but now can find it in Ohio. The project has also uncovered many previously unknown works and others that were considered lost. Researchers thought that there were no surviving copies of a 1710 tract that inspired author Jonathan Swift to begin a pro-government newspaper called The Examiner. The ESTC now records dozens of copies.

The ESTC alone could be the work of a lifetime. But for Snyder, who directs the Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research at the University of California at Riverside, it’s one of three major projects he’s worked on. The other two are the California Newspaper Project and the Catálogo colectivo de impresos latinoamericanos hasta 1851. Snyder notes that at the age of seventy he took on the newest of these, the online catalog of early printed works from Latin America, in 2000. He has since visited every national library in Latin America several times, eliciting tens of thousands of catalog records.

A sixth-generation Californian, Snyder has a special interest in the California Newspaper Project (CNP), which he joined in 1990 as part of an NEH initiative to preserve past issues of each state’s local newspapers. California, with more than nine thousand newspaper titles at fourteen hundred repositories, presented special challenges because of its size. Private companies, Snyder explains, had already microfilmed many of the newspapers. But some firms were going out of business or shifting focus, leaving the fate of the negatives uncertain. Over about fifteen years, the CNP acquired many of these holdings, amassing a 100,000-reel collection that includes new microfilms as well.

With its film archive largely complete, the center turned in 2005 to developing an online resource, the California Digital Newspaper Collection (CDNC). The CDNC has since launched its first offerings: searchable editions of the Daily Alta California from 1846 to 1891 and the San Francisco Call from 1900 to 1910. Early newspapers that covered San Francisco are especially important, Snyder explains, because they are among the few sources of information about the city before the 1906 earthquake and fire, which destroyed public records. Newspapers from other parts of the state will follow soon—although Snyder cheerfully notes that it would take five hundred years to digitize the project’s fifty-million-page archive using current methods. After a career working with computer-based projects, he is sure that advancing technology will leave that estimate in the dust before long.

For Snyder, the ESTC, the California Newspaper Project, and the Latin America catalog are each “a wonderful adventure in itself.” Looking back on decades of meetings, conferences, tireless travel, and shared information, he says, “it’s been a fascinating odyssey.”

—Esther Ferington

Ruth Wisse

YIDDISH IN AMERICA

Ruth Wisse traces her passion for teaching to the new Jewish immigrants who were her grade school teachers in Montreal. “I had brilliant teachers at my Jewish day school. These young men had no better opportunities. They were displaced intellectuals and went into primary education to our extraordinary benefit. They were engaged with life. At an early age I saw the calling of literature and teaching as inseparable from civic responsibility.”

Wisse has been a tireless advocate for a nearly lost literature. Through scholarly and popular books, anthologies, lectures, teaching, and helping to found libraries and archives, she has brought Yiddish writers to new audiences. Today, classes in Yiddish literature and Jewish studies are available at many American universities, and in 1993 Wisse became Harvard’s first professor of Yiddish literature.

But when Wisse wanted to study Yiddish literature in the late 1950s there were few choices. She went to Columbia University, one of the rare institutions to offer such a program. It was part of the linguistics department, but you could read Yiddish writers in the department of English and comparative literature. Returning home to Montreal, she pursued her interest by other means, getting a PhD in English at McGill University, but writing her dissertation on the “Shlemiel as Hero in Yiddish and American Fiction.”

As a teaching fellow there, she was able to start teaching Yiddish writers. Bit by bit, the classes she introduced led to a curriculum and eventually helped found a Jewish studies department. “I am proud that the university built this program without relying on private donors. To this day, I believe, there is only one endowed chair. McGill took the responsibility.”

Wisse was born in Czernowitz in what is today Ukraine, but was then part of Romania. Her father, a Lithuanian, had gone there to start a rubber factory. He received a medal from the king for his work, and this honor saved the family. It allowed him to take his family out of the country as the Russians advanced in 1940, going to Lisbon as “stateless persons.” From there they went to Montreal, where the family, with foresight, had bought a discarded textile factory—the Canadian government happily welcomed Jewish immigrants who were planning to create jobs.

The family spoke Yiddish at home, and Wisse considers herself a product of the thousand-year-old Yiddish culture that spread from Europe to America in the nineteenth century. She adores the culture’s variety and the sudden fits and unexpected turns of its assimilation in America, citing Emma Lazarus’s famous sonnet “The New Colossus” as an example. Wisse notes how it was Lazarus’s work with Jewish immigrants from Russia that spurred her to write about the Statue of Liberty. Lazarus’s words completely redefined the symbolism of the statue in New York Harbor.

“The STATUE was given to the United States by French republicans. She is holding a torch of liberty, which was supposed to represent what was passed from France to America—liberté, egalité, fraternité, shared between the Old World and the New. Along comes Emma Lazarus and writes a sonnet that is put at the base of the statue: ‘Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.’ [Lazarus] had worked with the new immigrants, people seeking escape from Europe. The passing of the torch from Europe to America is recast as American refuge from Europe.”

Wisse’s masterpiece is The Modern Jewish Canon: A Journey through Language and Culture, which presents decades of scholarship to the general reader. It makes the case for the centrality of Yiddish literature to any understanding of the modern Jewish experience. Wisse, though, calls the book merely “a signpost on an unfinished road,” knowing that literature must be argued about and inflame passions to survive. And that is the real challenge for a scholar of a dying language. “Yiddish was an expression of the Jewish way of life, but also of the degree of separation from the rest of European society. Once Jews wanted to become more integrated into their surroundings, they sacrificed the language that kept them apart.”

Yet Wisse notes the pluses too. “The possibility of assimilation is the greatest gift that America gives to the Jews. One should say a blessing for this possibility at Thanksgiving. Once there was great suspicion of what the Jews brought. Now there is a tremendous level of comfort.”

Wisse is a prolific commentator on the Jewish experience and politics. Her 1990 book, If I Am Not for Myself. . . : The Liberal Betrayal of the Jews, caused widespread debate with its analysis of American Jewish politics and the epigram-like quality of its insights: “Despite the unparalleled success of anti-Semitism, few university departments of political science, sociology, history or philosophy bother to analyze the single European political ideal of the past century that nearly realized its ends.” In 2007 she published a small book, Jews and Power, which argued that anti-Semitism has become a political phenomenon and can be understood today in no other terms. And she has grown more involved in the battles over the future of the universities. She views this work as inseparable from her scholarship. “The university has to be as good as possible. We must fight. My teachers took the same stands. We must all be upholders of certain values.”

—Robert Messenger