In the opening decades of the 1900s, the nation was gaining cultural independence. American artists were creating a new visual language born of the American experience.

Many of these painters and photographers went west in their search for an authentic American art. Others were raised in the West and retained its influences throughout their careers. As they depicted America west of the Mississippi—the wonders of its deserts and prairies, the allure of its Pacific Coast, and, as the century advanced, the anguish and displacement of the Dust Bowl-they honed artistic innovations that came to define American Modernism.

An exhibition opening this fall explores the power of place—particularly the geography of the West—in the development of American Modernism. "The Modern West: American Landscapes, 1890–1950" will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from October 29 through January 28 and then moves to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in March for three months.

"The exhibition and catalog integrate the art of the West into the larger story of American Modernism," says Emily Ballew Neff, organizing curator of the exhibition and curator of American painting and sculpture at Houston's Museum of Fine Arts.

The exhibition presents 120 paintings, watercolors, and photographs by 74 artists, including regional artists and Indian artists along with such well-known figures as Frederic Remington, Georgia O´Keeffe, Edward Weston, Thomas Hart Benton, Ansel Adams, and Jackson Pollock.

The exhibition begins with nineteenth-century American landscape painters, who were heirs to the Romantic tradition and whose paintings cast viewers as spectators of awe-inspiring scenery. A new generation moved toward Transcendentalism, applying the encounters between self and nature as did Ralph Waldo Emerson or Henry Thoreau and using the modernist tools of abstraction and distillation. With the 1930s came social realist and surrealist threads that chronicled America's loss of connection with place and nature.

The exhibition begins in the aftermath of the Civil War. The nation was expanding west, propelled by the belief that America was divinely ordained to transform the wilderness into fruited plains and shining cities.

In the 1860s and 1870s, firms hired artists and photographers to describe and publicize the uncharted terrain. The first section of the exhibition opens with an 1875 panorama by Thomas Moran, Mountain of the Holy Cross. Moran evokes a divine blessing on the mission of western expansion with a view of a mountain pass where snowmelt takes the shape of a cross.

Nearby is a tiny drawing by Bear's Heart, a Cheyenne incarcerated at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. Echoing the tracks of the railroad that penetrated his land, he sketches a relentless blue line of soldiers attacking a settlement in U.S. Troops Amassed Against a Cheyenne Village.

The transcontinental railroad was the engine of expansion into the West. In a photograph by Carleton E. Watkins, Cape Horn, near Celilo, railroad tracks converge with the land on the horizon, suggesting a merging of the technological and natural. In contrast, Timothy O'Sullivan's Sand Dunes, Carson Desert, Nevada is an elegiac image of horse-drawn wagons as they cross an engulfing prairie.

By 1890, the U.S. Census Bureau had declared that the West was no longer a frontier. In the section, "The End of the Frontier: Making the West Artistic," Remington sets lone, heroic figures—cowboy and Indian alike—against wide horizons in scenes that serve not the aspiration of nationalist expansion but rather a dream of the Old West.

Among the photographers is Laura Gilpin, whose The Prairie shows a woman standing alone on an endless plain, her diaphanous white dress billowing like the clouds overhead.

The sheer drama of Yellowstone was a magnet for artists. In Yellowstone "Grand View,"Louise Deshong Woodbridge's photograph eliminates the sky to create a vertiginous view into a Yellowstone valley. Roiling rapids snake across the flattened composition, its only hint of depth a downward slope of pine trees. John H. Twachtman applies an Impressionist's eye to Yellowstone's primeval bubbling mud pots. Augustus Vincent Tack, a protégé of Twachtman's, dissolves mountains into ocean waves flecked with golden light in his evanescent Storm.

The galleries explore the symbiosis between artist and place in three regions: California, the Southwest, and the Midwest.

Dominating the California space are two thirteen-foot murals by Gottardo Piazzoni, The Sea and The Land. The bounty of land and sea are a motif. In paintings by Seldon Connor Gile, the richness is reflected in the ochre of the California soil; in the painting, Evening Sun (Poème du Soir) by Frank Cuprien, the color is the lush lavender and gold of the Pacific surf. Although turn-of-the-century critics had scorned this palette as an outdated cliché of "the Monet gang," its extravagance matched the scene.

Modern photography also came of age in the West, evolving in parallel with painting from illustration to abstraction. Asahachi Kono's luminous Untitled (Tree and Hills) done in the late 1920s has the formal elegance of a Japanese woodcut.

Aiding the development of photography were new tools and techniques. The iconic Ansel Adams photograph Moonrise over Hernandez, New Mexico 1941 shows a cemetery at the moment that it is lit by both a setting sun and a rising moon.

The Southwest was a magnet for artists from elsewhere, particularly Manhattan, who were seeking a more authentic America. Colonies of artists descended on Taos and Santa Fe in what Neff describes as "an artistic land rush."

Along with work by regional artists, the section on the Southwest contains paintings by Georgia O´Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Paul Strand, whose works were promoted by New York gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz.

In New Mexico the artists found Pueblo and Navajo communities whose ancient ways of life offered a healing antidote to a materialistic modern age that had severed its connection with nature. And American Indian art was abstract and emblematic-qualities that appealed to modernists.

Semi-abstract shapes abounded in the austere Southwestern landscape, from its snow-capped peaks and curved adobe structures to its vast desert. The intense sun blurred distances and flattened forms. Defying the conventions of one-point perspective, the geography encouraged artists to juxtapose planes rather than impose the illusion of depth.

Raymond Jonson's Cliff Dwellings, No.3 is a layered image that captures the jagged, precipitous, and otherworldly grace of the soaring, pinnacled homes. Marin painted plane-shifting watercolors, and Hartley created surreal, turbulent landscapes free of a focal point.

Georgia O'Keeffe spent the last four decades of her long life in New Mexico after the death of Steiglitz, who was her husband. Turning her eye from skyscrapers to the desert, she created images of spare intensity. She magnified a shell, bone, or flower and set it against a distant landmark, compressing the near and the far in paintings that were at once descriptions and abstractions. "Half of your work is done for you," she said of her adopted home.

Meanwhile, in the Great Plains, artists were helping to create the myth of the Midwest as heartland. In the section titled "The Dust Bowl Era—Plains and Other Places," increasingly surrealistic paintings and photographs convey the region's rise and fall as a promised land.

Instead of lone figures and vast landscapes, these works show people close up, going about their daily labor. Human qualities extend to the land, which artists anthropomorphize. In Grant Wood's Spring Turning, the rolling farmland swells with fecundity.

But after years of drought and overuse, the plains became wastelands wracked by whirlwinds and oceanic dust storms. A cross-shaped scarecrow juts out of the parched, exhausted soil in Alexandre Hogue's Crucified Land. Injected with the swirling, dream-like energy of a painting by Albert Pinkham Ryder, Thomas Hart Benton's The Hailstormshows a farmer gripping his plow to stead his frightened horse.

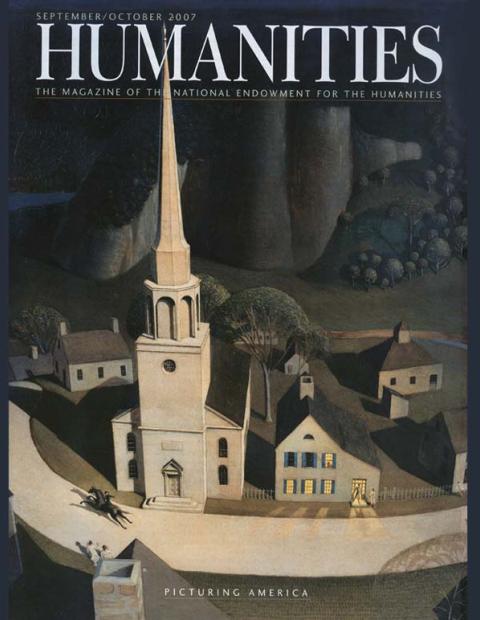

As artists charted the Depression and the Dust Bowl, they inserted ironic juxtapositions into their landscapes, such as billboards advertising consumer goods on barren, dusty plains. Instead of adobe dwellings rooted in the earth, protruding verticals—telephone poles, steeples, and oil derricks—pierce the barren terrain.

The concluding section shows how artists sought new ways to bear witness to this rupture or to heal it. Departing from the idyllic mood of her earlier Pictorialist landscapes, Gilpin uses a filter to darken the sky against stark dunes in her lunar image, White Sands, which she photographed near the test site of the first atomic bomb. Clyfford Still layers paint on canvas to create his own raw geology with 1954. Its large, encrusted surface evokes the fissures of the earth.

An equally potent work is a drip painting by Jackson Pollock, No. 13A Arabesque. Pollock came to believe, like the Indians, that nature resided within oneself and, through the semi-spontaneous choreography of drip painting, he found a way to transfer nature onto canvas.

Wyoming-born Pollock was the fifth son of a struggling dairy farmer. When Pollock moved to New York City in the 1930s, he continued to pursue his lifelong interest in American Indian art and religion. Together with the tools of Surrealism and Jungian analysis, Indian art provided him with a structure for exploring his psyche.

Spreading his canvas over the floor, he could, he said, "work from the four sides and literally be in the painting. This is akin to the method of the Indian sand painters of the West."

Behind Pollock's Arabesque in the exhibition, a small gallery brings these rituals together. On the walls are prints of sand paintings drawn by Navajo religious figure Jeff King during a ceremony for Navajo men drafted for World War II. Artist Maude Oakes gained permission to replicate the images, which use simple geometric forms to depict the perilous rite of passage of two boys who journey to find their father. After a series of tests, they emerge as heroes. Videos show Navajos conducting a sand-painting ceremony (The Spirit of the Navajos by Maxine and Mary J. Tsosie, 1966) and Pollock making a drip painting (Jackson Pollock by Hans Namuth, 1950).

Heir to the abiding American reverence for nature, Pollock went further than the Romantics, who cast the viewer as a spectator of virgin wilderness, and went beyond the modernists whose semi-abstract works immersed the viewer in transcendent moments. In a world that had ruptured it connection with the earth, Pollock transferred nature from within himself onto the canvas. His drip paintings blended new ideas with the ancient traditions of the West.