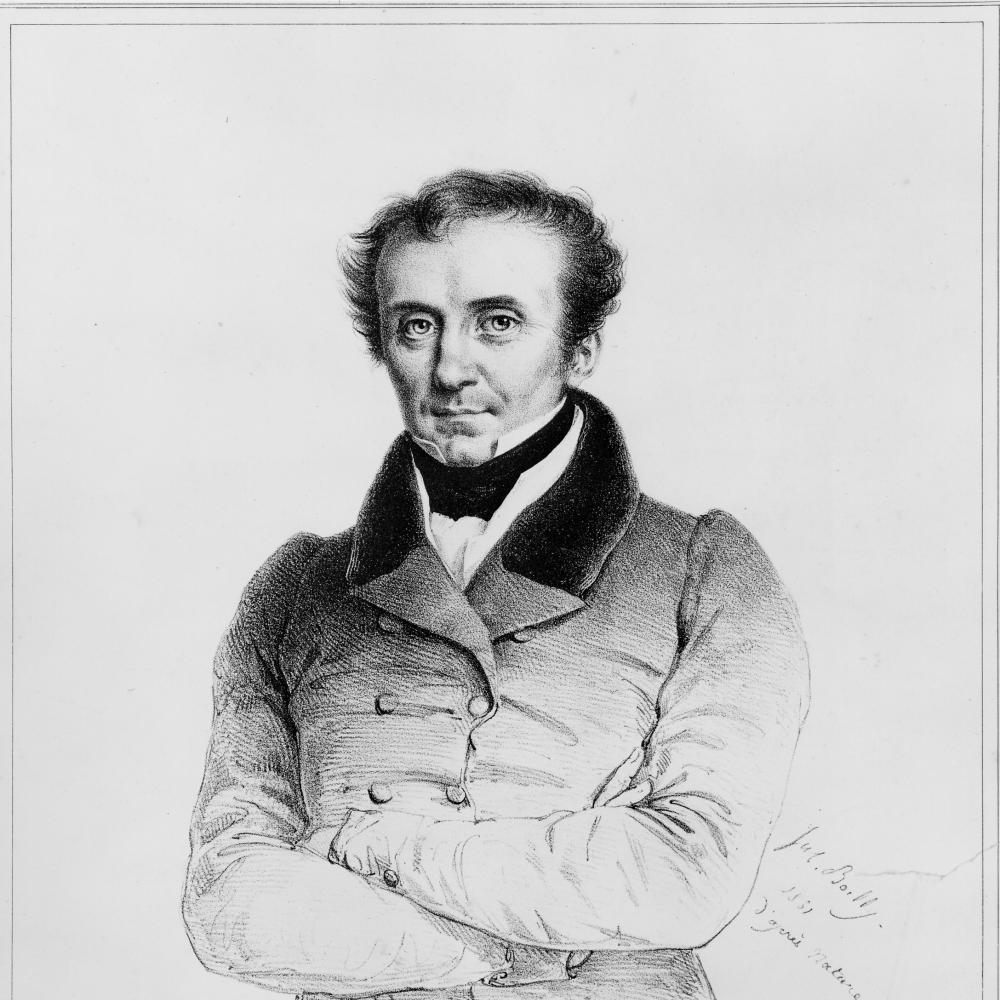

AUTHOR OF THE FAMOUS five-part Leather-Stocking series, twenty-seven other novels, and a box of historical and miscellaneous works, James Fenimore Cooper remains one of the most innovative yet most misunderstood figures in the history of American culture. Almost single-handedly in the 1820s, Cooper invented the key forms of American fiction—the Western, the sea tale, the Revolutionary romance—forms that set a suggestive agenda for subsequent writers, even for Hollywood and television. In producing and shrewdly marketing fully 10 percent of all American novels in the 1820s, most of them best sellers, Cooper made it possible for other aspiring authors to earn a living by their writings. Cooper can be said to have invented not just an assortment of literary genres but the very career of the American writer.

Despite Cooper's importance, he continues to be profoundly misunderstood, and this is partly his own fault. Although it was becoming common for writers in the early nineteenth century to indulge public curiosity about their lives, the usually chatty Cooper turned reticent when asked for biographical details. Whereas contemporaries, such as Sir Walter Scott and Washington Irving, made prior arrangements for authorized biographies, Cooper refused to follow suit. When nearing death in 1851, he insisted that his wife and children protect his life and his papers from outsiders. His private documents remained out of reach to most scholars until the 1990s.

The biographical problem is only one reason for Cooper's languishing reputation. Another reason is that he's always been the object of strong feelings, pro and con. Almost from the start of his career, Cooper was admired, imitated, recited, and memorized. In his day, he was reportedly the foreign author most widely translated into German, and what has been called “Coopermania” hit France especially hard as early as the 1820s. Yet, from the outset, he was also subjected to various criticisms that, when combined with later politically motivated assaults, have hampered true appreciation of his work. Critics at times faulted him for his unconvincing treatment of genteel characters, his occasional bad grammar, his leisurely pacing, and his general inability to eclipse his greatest contemporary, Sir Walter Scott.

The criticisms were not without merit. But the problems in Cooper's first books need to be understood in their proper context. At least some of Cooper's failings were owing to the very newness of what he was attempting. As an American venturing into a field where few of his fellow citizens had had any success, he was undertaking something quite different from what Scott had accomplished. It was hardly clear at the time how American materials (the frontier or the Revolution, for instance) might form a basis for literary art. Robert E. Spiller summed up this point in 1931 by noting that Cooper “always suffered from the crudities of the experimenter.”

Nor was he a perfectionist. He couldn't afford to be, because, more than anything else, Cooper, at the start of his career, was driven by an imperious need for money. After his father's death in 1809, Cooper watched as the large inheritance he had been promised simply evaporated. By 1820, Cooper was so desperate for resources to pay current bills and old debts that, madly reasoning from Scott's literary success with the Waverley novels, he launched his own career in the expectation that it would solve all his financial ills. The need for cash kept Cooper pushing production as, had there been more time and money, he probably would not have done. Not until he had written several books was he at last in a position to enjoy a good return on new projects; then he could attend to the early criticisms.

Publishing was itself a slowly emerging trade. Before 1826, Cooper produced his books completely at his own risk, employing first one and then a second New York bookseller as his agent. Those men made all the practical arrangements with paper suppliers, printers, binders, and wholesale and retail merchants, but they were not responsible for editing the books, reading proofs, or giving Cooper any regular form of advice—activities that would eventually form a major part of the publisher's functions.

Under such conditions, it is remarkable that Cooper managed to see most of his projects through to completion. But as they succeeded, it became possible for him to negotiate an advantageous arrangement with the Philadelphia firm of Carey & Lea, one of the nation's pioneering publishers. Cooper was their first author, and for many years America's most lucrative. When Carey & Lea paid him $5,000, a princely sum in 1826, for The Last of the Mohicans, no one could doubt that “American literature” had become a cultural and economic commodity. As early as 1824, one American magazine humorously portrayed an unnamed New York publisher as swamped with imitations of Cooper (replete with “the backwoods, an Indian, a panther, and a squatter”), for which the ambitious authors were demanding high prices and half the profits. Such a joke, unthinkable when Cooper began writing a mere four years earlier, indicated his influence on the American literary marketplace.

Cooper was also recognized by later writers whose careers he enabled. Herman Melville paid him generous tribute. Born when Cooper started writing his first books, Melville had grown up on them. He especially devoured the sea tales. Later recalling the "vivid and awakening power" they had exerted on his young mind, Melville declared in 1852 that Cooper was “a great, robust-souled man.” Melville trusted that time would restore Cooper to his rightful place: “a grateful posterity,” as he put it, would “take the best care of Fenimore Cooper.”

In the later decades of the nineteenth century, fresh editions of Cooper's works continued to appear, indicating his strong residual appeal among ordinary readers. At the same time, his stock in the contemporary literary world began a long downward slide. So low did his reputation sink by the 1880s that the scholar Thomas R. Lounsbury's tepid praise in his biography of Cooper was enough to push Mark Twain to commit the most famous literary assassination—an essay that is better known to many readers today than any of Cooper's own books.

In that essay, Twain attacked “Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses” with a comically ex post facto insistence on the universality of the laws of realism. Considered as a creative work in its own right, the essay appears ingenious; considered as a critical estimate of one writer by another, however, it is both unfair and dishonest. It conceives of Cooper as obtuse and a failure, when in fact he was neither. He was being true to his age, which was a romantic more than a realistic one.

Also, it is fair to say that without Cooper, there could have been no Twain. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a prime example of the pervasive influence of Cooper's innovations. The spiritual father of Huck Finn was none other than Cooper's Natty Bumppo—a demotic Euro-American hero who resists the confines of “sivilization” and, with a member of another race as his companion, finds his freedom in nature.

Cooper's most innovative work as a writer probably lay in the field of sea fiction. Before The Pilot in 1824, writers had used the sea only minimally; when it figured in novels and tales at all, it served largely as a backdrop for social or moral action. Cooper felt that the actual sea, the sea he had known as a merchant sailor and midshipman, had barely entered art and literature. When he discussed Scott's nautical romance, The Pirate, with friends in New York City in 1822, he was surprised to hear the author praised for his intimate familiarity with the sea. Cooper to the contrary thought that Scott had never actually gotten his feet wet. Cooper's own book was meant to show exactly what a sailor might do with the subject. Opening with a gale off the English coast that nearly wrecks two American vessels, The Pilot at once established Cooper as a master of this new environment. From 1824 on, anyone who made literary use of the sea did so in Cooper's wake.

Cooper's sea fiction made him more accessible to writers from other cultures than his forest tales ever did. The Anglo-Polish writer Joseph Conrad was as impressed as Melville by “the true artistic intent” with which Cooper had imagined the sea. “In his sea tales,” Conrad wrote in 1898, “the sea inter-penetrates with life; it is in a subtle way the problem of existence, and, for all its greatness, it is always in touch with the men, who, bound on errands of war or gain, traverse its immense solitudes.”

As important as Cooper's sea tales were, he remains better known today for his wilderness novels. Cooper himself concluded that the center of his achievement lay in the five Leather-Stocking Tales, a mythic chronicle stretching from the 1740s to the time of Lewis and Clark and capturing key epochs of American life.

In his frontier fictions especially, Cooper helped set the terms of American dreaming. That he made his myths complex, full of concern for the fate of the leveled continent and the scattered native populations, meant, too, that he did not merely cheer on the wanton “progress” of Euro-American pioneers. Cooper appreciated the great energy that ordinary settlers expended in moving west, and the heroic visions that drove them. But he was never blind to the pettiness, the squalor, the wastefulness, or the injustice happening.

The sad slaughter of the passenger pigeons by the inhabitants of the village of Templeton in The Pioneers is a case in point. In Cooper's youth, those birds had been legendary for the enormous flocks that darkened the sky all across the East. At his death, they were in precipitous decline because of overhunting, and in 1914 the last one died in the Cincinnati Zoo. In his warm response to the book, D. H. Lawrence enthused over Cooper's description of the “clouds of pigeons flying from the south, myriads of pigeons, shot in heaps.” Cooper directed his reader's attention to the pathetic eyes with which the wounded birds, lying in those heaps, look up at Natty “as if they only wanted tongues to say their thoughts.” Judge Temple, whose own enthusiasm for the hunt dies in the pigeons' pain, takes Natty's hint: “I see nothing but eyes, in every direction. . . . I think it is time to end the sport, if sport it be." Cooper understood that even the tender mercies of the wicked are cruel; the judge recruits the village schoolboys to end the suffering of the birds by twisting off their heads. He will pay them six cents per hundred on delivery. By such means, Cooper insisted, does nature become "ours.”

Here was the beginning of an American environmental conscience. Thinking back to his own youth, Cooper remembered the naïve destructiveness of the earlier era and endeavored to set it right. Thoreau, who read Cooper while at Harvard in the 1830s, imbibed the core message from his frontier novels. Later, at Walden Pond, Thoreau sought what Cooper had urged Americans to imagine or discover—a relation to nature that did not destroy the wild but rather cherished and internalized it. In Natty, Cooper had shown the way.

Cooper was not just a pathbreaking figure in the history of writing in the United States, or a potent visionary of forest and sea; he was a remarkably representative man. He was as much at home in the salons of New York City or the country houses of the rural Hudson Valley as in the raw frontier villages where his family's life had taken its root and rise. Knowing the country's most characteristic landscapes in ways that few of his contemporaries did, Cooper wrote of them with unexampled authority. In a similar fashion, his experience in the merchant marine took him to Europe at the height of the Napoleonic conflicts, a time of immense importance to American interests. He closely followed the War of 1812, partly because his friends fought in it and partly because so much hinged on its outcome. Cooper thereafter joined in the effort of his most influential contemporaries to forge a new culture for the reaffirmed nation. One might say that Cooper's story is almost incidentally a literary story. It is first a story of how, in literature and a hundred other activities, Americans during this period sought to solidify their political and cultural and economic independence from Great Britain and, as the Revolutionary generation died, stipulate what the maturing Republic was to become.