This issue of Humanities magazine has two themes. Or perhaps one. There is Picturing America, a major new NEH initiative to bring great works of American art to classrooms across the country. A potentially second theme, depending on your point of view, is American art itself. And yet I am aware that a certain type of bottom-line accountant would say there is but one theme here: the American story.

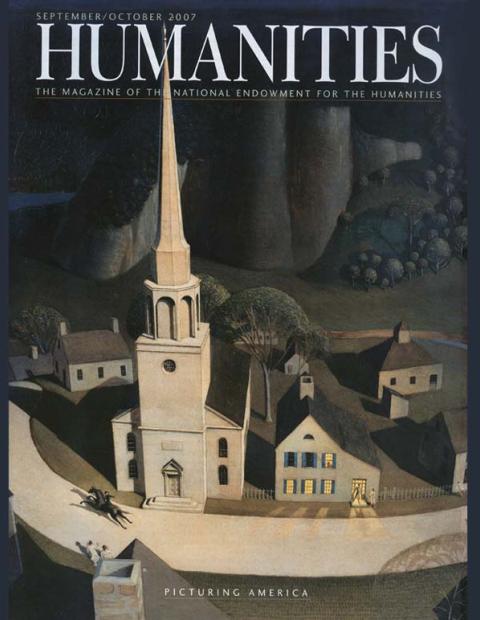

The purpose of Picturing America is to promote art education and to promote art as a part of the humanities curriculum. The plan goes into action quite soon. Packages of double-sided laminated reproductions featuring forty of the most beautiful, inspiring, and resonant images of American art will be arriving this fall on recipients' doorsteps.

In part, my counting confusion derives from this program's fearlessness in the face of artificial boundaries opposing art, as a matter of pure imagination and occupying a completely fantastical realm, and the humanities, as the scholarly inquiry into what really is or was. Such boldness is well-placed, for in relaying the ideas and achievements of our nation, artists have obviously had much to say.

The story of American art can even be recast as the story of America itself. (To further illustrate the overlapping themes of this issue, I'll cite only artists and works of art from Picturing America. For a complete list of those, see p. 9.) You have the early colonial portraits of craftsmen—John Singleton Copley's portrait of Paul Revere—and the grand neoclassic, historical images by painters such as Emanuel Leutze and Gilbert Stuart. This is the America—commercially spirited, politically innovative—that produced the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, documents of world-historical importance and astonishing optimism.

With the arrival of the Civil War came the birth of modern photography and the insertion into public life of another great image of American art: the face of Abraham Lincoln, the most photographed man of his time. We have in Alexander Gardner's celebrated photo a scientifically precise record of Lincoln's deeply-shadowed, prophet-like visage. Gone is the grand rhetoric and imagery of Washington's time. In its place, we see a great nation suffering through its most trying hour.

The twentieth-century images of American art are appropriately emboldened and yet self-critical. We turn away from the nineteenth-century Western landscapes of Albert Bierstadt and the quiet poetry of Winslow Homer. In their places we find the Chrysler Building's cocky assertiveness but also the mechanized, disassociative landscape of Richard Diebenkorn, followed by a renewed and rehumanizing interest in American character. I am thinking of Romare Bearden's important collage, The Dove, of a Harlem street corner and the great civil rights photo "Selma-to-Montgomery March for Voting Rights in 1965" by James Karales.

In this latter, post-World War II period, collectors and scholars, as discussed in this issue's "conversation" between Chairman Cole and the eminent American art collector and historian William H. Gerdts, begin to take our nation's art very seriously. America and American art achieve self-conscious greatness somewhere around the middle of the last century, even as we begin to ask ourselves, What have we become?

Picturing America uses our national store of artistic achievement to relate and reinforce the lessons of We the People, whose mission is to increase the teaching and understanding of our nation's founding principles. From American Indian culture to the bold republican experiment of our Founders, from the crisis of Civil War to the modern America of the twentieth century, Picturing America helps tell the story of the nation that adopted and grew out of those principles. Its lessons begin with art, expand into history, cross into literature, and even touch upon science and math.

Thematically, then, this issue contains multitudes. Or, as the founding accountants put it, E pluribus unum.