As Ralph Alan Cohen sits in his office at Mary Baldwin College in Staunton, Virginia, talking about how he thinks Shakespeare's plays should be acted and staged, his leisured Alabama drawl begins to turn rat-a-tat. A scholar of Shakespeare and the founder of a prominent theater company devoted to Shakespeare, he is complaining about how pretty much everyone else in the theater world approaches and stages Shakespeare's plays. That objection, it begins to dawn on his listener, is not simply that these other productions fail to entertain but, in a much broader sense, to do right by their audiences.

Imagine, Cohen says, “I'm the Royal Shakespeare Company. And we are the gold standard as far as everyone's concerned. And a guy comes in. He says he wants to be the artistic director for the RSC. He's applying for that job. He says, 'Boy, do I love Shakespeare. I'm going to do all the plays. All the plots, characters. In fact, we're going to do original costuming.'”

Cohen's imaginary guy says he'll do that and everything else associated with Shakespeare's original staging practices to faithfully render the plays and create an authentic Elizabethan theatergoing experience.

“'The only thing is,' the guy says, 'we're not going to use his words.'” This, of course, is ridiculous. Who would think of producing Shakespeare's plays without his words? Cohen continues: “But if the same guy came in and said, 'I'm going to do all of his words . . . but I'm not going to worry about embedded stage directions [and] I'm not going to worry about his stagecraft,' he'd be like every other director directing Shakespeare right now.”

This is no idle scholarly digression. Cohen is a professor of literature; but also an artist who has made it his life's work to demonstrate that Shakespeare's plays improve with the use of original staging practices. The basics of Shakespeare's stagecraft-whether these were merely conditions imposed by his time and place or essential to his artistry is, of course, a matter of debate-include such practices as universal lighting, “doubling,” or the use of actors in more than one part in a single play, plain sets, brisk pacing, and live music. This much of Shakespeare's stagecraft, Cohen and his organization, the American Shakespeare Center (formerly Shenandoah Shakespeare), have embraced.

“The most important stage direction of them all,” however, is universal lighting. The audience sits not in darkness but in full illumination, as visible to actors' eyes as the actors are to theirs. “Shakespeare1v Cohen adds, “never put on a play in front of an audience he couldn't see.”

Cohen may sound like some overwrought true believer trying to answer the question, What Would Shakespeare Do? But it is no heavenly reward for historical accuracy that lures Cohen and Co. to “do it,” as their cheeky bumper stickers put it, “with the lights on.” Actually, their productions are often gleefully anachronistic (though Shakespeare was too, for that matter), using rock music, modern allusions, latter-day costuming, female actors, and much else that might disappoint the more antiquarian-minded.

No, keeping the lights on serves a more dramatic purpose: It makes good on what is the mother truth of Cohen's philosophy of Shakespearean performance and production. "The audience," he says, "is written into the play."

Here is the idea, the insight, the bold assertion that reveals how a little amateur theater company in rural Virginia, consisting of full-time college students stealing away from the James Madison University campus to go on the road, led by a professor of English with no significant theater experience, has grown into a critically acclaimed, full-time nonprofit theater company with two troupes, its own made-to-order theater, a Master's program, an international reputation, and plans to become the center of the modern-day Shakespeare universe.

“THE AUDIENCE IS WRITTEN INTO THE PLAY.”

Starting in 1974, Ralph Alan Cohen, then a young professor of English at James Madison University, began taking groups of students to London to see productions of the Royal Shakespeare Company. A semester-abroad program soon grew out of Cohen's realization that literature students responded better to Shakespeare's plays as theater. Cohen, who has authored a book on teaching Shakespeare and trains Shakespeare teachers through Mary Baldwin's graduate program, is a big advocate of staging brief scenes in class to accustom students' ears and imaginations to the acting out of the plays they read.

Over the next ten years, Cohen caught every production the RSC did. He recalls seeing Jeremy Irons as Richard II in February 1986, a highlight one would think, but his students were unimpressed. The year before they had caught, and enjoyed far more, a production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, performed briskly and without directed stage lighting by the innovative Cheek by Jowl company at the Donmar Warehouse. “Because of the spill from the lighting, everybody could see everyone,” Cohen recalls. Suddenly, “we're in a show together”—“we” meaning audience and actor alike.

What would happen, Cohen remembers wondering, if he directed a show at JMU using such lighting and other (though more intentional) original practices, a term he acknowledges is "much debated." During this same trip, Cohen and his students met Patrick Spottiswoode, who was then running the Bear Garden Museum and serving as a spokesman for actor-impresario Sam Wanamaker, whose decades-old dream to reconstruct the Globe Theatre in London later became reality in 1997. Spottiswoode, who is now education director at Shakespeare's Globe in London, says that the playhouses Shakespeare worked in are analogous to the particular instrument for which a piece of music is composed. Performing Shakespeare's plays in a space for which they were not written is like, he says, playing music written for a pianoforte on a Casio keyboard. It was from Spottiswoode's sales pitch about original practices unleashing the true power of Shakespeare's language and theater that Cohen began to learn the talk that would help him market and defend his own efforts.

In the fall of 1987, Cohen taught a seminar on Shakespearean stagecraft, focusing on Henry V, which led to a production in the spring with then JMU student Jim Warren as Henry in a warehouse-like space fixed up to look like a traditional Elizabethan yard. The production used fifteen actors, equal to the greatest number of characters on stage at one time. And whether or not it was a hit, the cast had a great time, leading Warren to suggest to Cohen that they start a traveling company.

Cohen agreed. He felt he had to, he says, on principle. "If I said no, I would be denying that this stuff would work." Thus was born the Shenandoah Shakespeare Express, a no-frills, in-your-face road company that worked cheap, played fast, and was not afraid to embrace the Bard's bawdier side. Their first show was a two-hour-and-twenty-minute Richard III, its length reduced by editing and pacing. It was a modest tour of rural high schools, fourteen shows in all, but the company, despite the confusing and dark historical play it was performing, was very well received.

Two years later came the company's big break when they performed Julius Caesar for a roomful of scholars at the Shakespeare Association of America in Philadelphia. Beforehand, Cohen was terrified, afraid these high officers of the Shakespeare establishment would hate his work and expose him as a dilettante, but instead “they loved it.” Around the same time, Stephen Booth, a prominent Shakespeare scholar, wrote about the company in the Shakespeare Quarterly: “I first saw The Shenandoah Shakespeare Express perform in Washington, D.C., in July 1991. I haven't thought the same since about Shakespeare or the theater.” Word spread to college campuses and student activities committees, leading to a much-increased volume of work. In 1992, Shenandoah Shakespeare began paying its actors.

“IF YOU BUILD IT, THEY WILL COME.”

In 1596, James Burbage, father of the storied actor Richard from Shakespeare's own company, bought some property that had been a part of a friary. Though it lay within the walls of London, the land and building came with a “liberty,” allowing it, in theory, to be used as a theatrical venue. Still, it took twelve years for Burbage's syndicate of investors, which included Shakespeare himself, to stage a play at Blackfriars Hall, which was also England's first indoor playhouse.

Smaller than the Globe, the more famous outdoor theater where Shakespeare's plays were performed, the Blackfriars was an upscale establishment that charged a premium for admission. In addition to protecting audiences from the vagaries of English weather, the Blackfriars could accommodate evening performances. Home of Elizabeth I's and then James I's favorite theater troupe, it was the place to be. “Gallants,” writes Stephen Greenblatt in his book Will in the World, “eager to show off their clothes could even pay to sit on the Blackfriars stage and become part of the spectacle.”

Demolished in 1655, Blackfriars has survived only in memory, which is to say court papers, probate records, and building plans for other theaters. Nearly four centuries later, it became a point of inspiration for Cohen and the other folks at Shenandoah Shakespeare.

In 1995, Cohen and his team received a grant of nearly $200,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities for a six-week summer institute on Renaissance and Shakespearean staging. For their grant application, Cohen and then marketing assistant Paul Menzer came up with a name for the institute: CRASS, which stood for Center for Renaissance and Shakespearean Staging. The acronym, though real enough, was also a private joke about the vulgar financial logic behind such practices as hiring as few actors as possible and not building any fancy sets.

The institute was nevertheless a big success, resulting in working groups and productions inspired by discussions and presentations at the institute. Bringing together scholars and actors in Harrisonburg, it also enabled Cohen to further explore a recurring theme in his own work: overcoming modern divisions between theory and practice, scholarship and performance, stage plays and the study of literature. Just as Cohen has turned literature students into theatergoers, he eagerly treats his actors as fellow students, if not scholars, of Shakespearean literature.

In such a spirit did this road company become the basis for a nonprofit with educational programming. And the educational programming-group ticket sales to student groups, educational tours, a public lecture program, scholarly conferences, etc.-helped justify the creation of a resident acting troupe. In 2001, these later developments coincided with Cohen's appointment as full professor at Mary Baldwin College, where he heads up an MLitt/MFA program that trains actors, teachers, and dramaturgs in Shakespeare and Renaissance literature. In 2003, Cohen retired from James Madison University.

As Cohen says in another context, “Shakespeare didn't wake up in the morning and say, 'I'm a writer not an actor, or I'm an actor not a writer.'” Cohen himself clearly doesn't wake up, saying “I'm a theater person, not a scholar, or I'm a scholar, not a theater person.” Specialization is the very un-Shakespearean obstacle here, to be avoided because it inhibits both the performer's mind and the scholar's urge to think in terms of the stage. Such logic has other consequences. American Shakespeare Center actors, for instance, undergo an unusually rigorous classroom-like rehearsal routine, devoting a quarter of their preparation to “table work,” during which they scan for meter and paraphrase every single line of the play they are performing.

STOCKYARD SHAKESPEAREANS

One of the scholars visiting CRASS in 1996 asked Cohen whether he realized there was an Elizabethan theater right there in Harrisonburg. He then walked Cohen, who realized he was being put on, over to a stockyard. The building had a door for cattle to come in, another for them to leave, and a stand for the auctioneer. Put another way, it was a simple theater in the round. Amused, Cohen got permission to borrow the space, brought in some of his actors to perform, and called the local newspaper, who sent over a photographer to document the stockyard Shakespeareans.

Joe Harmon, a former hotelier in Staunton, saw the photograph and called Cohen up. Would you, Harmon asked, be interested in building a theater in Staunton?

This intriguing idea, however, didn't go anywhere beyond some meetings of a local booster association until, in 1998, another group in Richmond, led by Peter Wiggins of the College of William and Mary, thinking of building a re-creation of the Globe in their fair city, approached Shenandoah Shakespeare to see if they might be interested in playing a part. “All I can say is,” Cohen gently adds, “the [local] effort intensified.” And it took a new shape. So long as they were building a re-creation, the new thinking went, why not re-create Shakespeare's indoor Blackfriars playhouse?

Shakespeare Wars author Ron Rosenbaum called it a theatrical “field of dreams” after the opening in September 2001. Without blueprints of the original Blackfriars, architect Tom McLaughlin had to base his design on surviving Tudor structures such as Westminster Hall and plans for later theaters whose construction was influenced by the Blackfriars. Scholarly research became as important to the design as modern building codes and a requirement to fit the theater among the other buildings of Staunton's historic downtown district. Various compromises with historical accuracy were inevitable. An elevator was installed to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

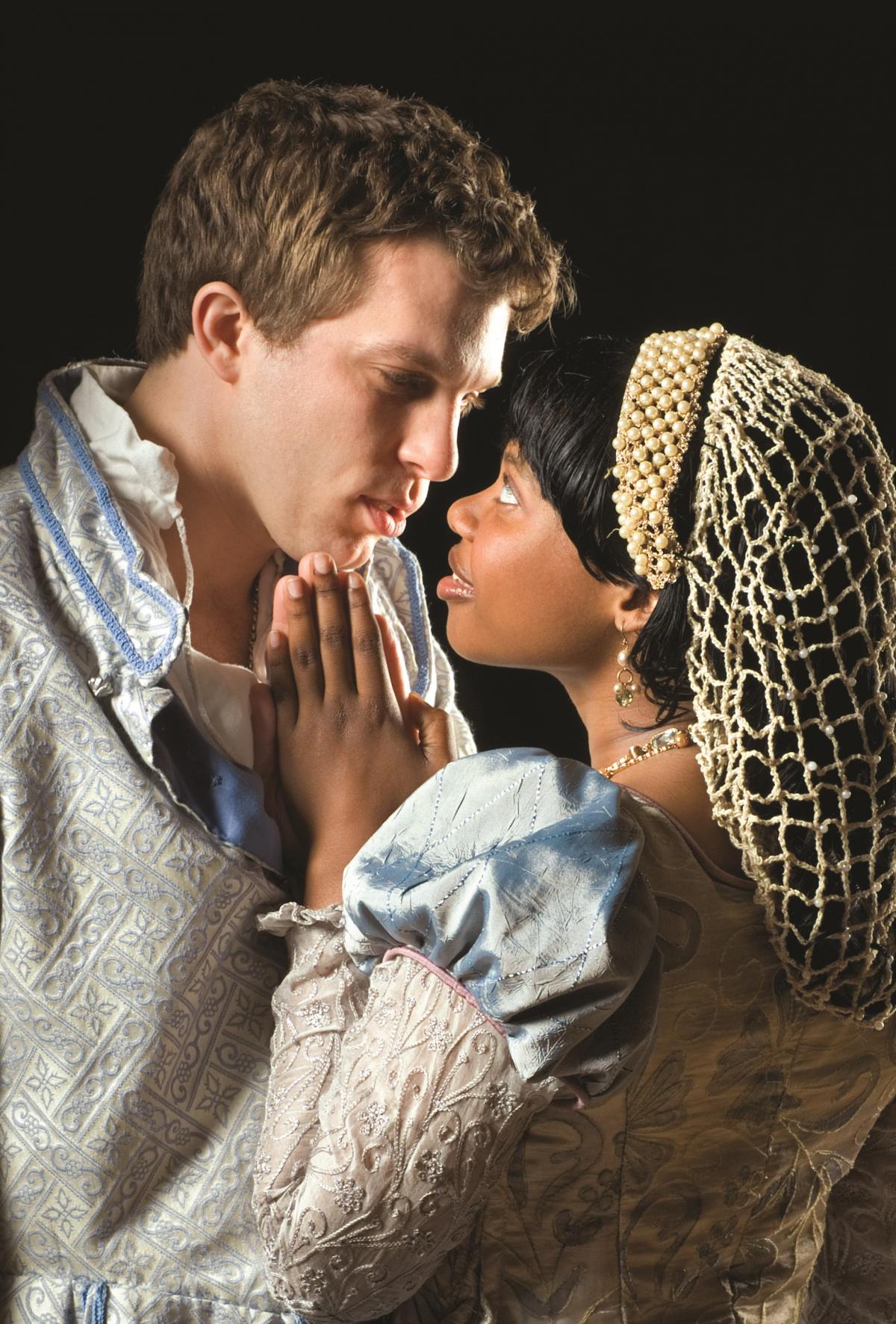

The final product is a gorgeous and cozy all-timber theater constructed entirely of Virginia oak tucked inside a modern storefront with modern rehearsal space and greenrooms built underneath. Handmade candelabras suspended from chains provide the theater's simple room-style lighting. Audience members can sit on the stage, enjoy a “Lord's Chair” (which comes with armrests), or take a seat among the rows on the floor below the stage. As the actors explain before the show starts (never a pedagogical opportunity wasted here), “You can see us and we can see you.” The actor is thereby free to use the audience, to address lines to individuals, to look you in the eye.

The effect is exciting, and even unsettling. An unusually personal connection develops between audience and performer wherein the audience is more fervently rooting for the actor. The separate realms of performance and make-believe both receive their due, while the tiresome idea that actors must inhabit some separate reality from which the audience need vanish is revealed as modern prudishness about the messy, hammy, slaphappy greatness of theater's golden age. The enjoyment of theater, one learns, does not necessarily depend on the illusion of transport into the play's sacrosanct inner world.

And the pathos of the play is even more keenly felt as it is shared. An audience member (to cite this writer's own experience) who occupied a Lord's Chair for a performance of A Winter's Tale and bawled his eyes out as Leontes, in an irrational fit of Othello-like jealousy, persecutes and imprisons his faithful wife Hermione (so unjustly!), would have been seen by just about everyone searching frantically for a tissue. Universal lighting thus liberates the actor and recruits the audience member.

“That's why there are no long speeches in Shakespeare,”" says Cohen about universal lighting. “A long speech is when an actor comes out and he acts to the exit light.” What Cohen tells his actors and students is that Shakespeare's speeches are really uninterrupted dialogue. Quoting Enobarbus from Antony and Cleopatra, Cohen stretches forward in his chair and begins to speak, “I will tell you. The barge she sat in, like a burnish'd throne.”

Then he waits for the silent ping of understanding from his listener before continuing. “Burn'd on the water: the poop was beaten gold.” The breaks between individual thoughts are crisp, and the delivery seems conversational. The listener might interrupt, but doesn't. The words thus spoken regain their ability to amaze.

COMMUNITY THEATER

The term community has become so debased that one might, upon hearing the word, immediately suspect its absence. Not here, where the community is the audience and the audience is important. “The first thing you do when you walk out on stage is cast the audience,” ASC co-founder and director Jim Warren tells his actors. The audience is the butt of jokes, a character in its own right, a major one even, like Hal's army on St. Crispin's Day. And theater is, in Cohen's telling, about community. It is, or rather should be, “a general expression of public activity that belongs to everyone.”

Here, in Staunton, the community is a town full of Shakespeare aficionados with many an audience scholar happy to explain during intermission that live music is actually very traditional in a Renaissance setting, though, no, that particular song by The Killers was not. Here the community has helped build one Shakespearean theater and is coming on board for something even bigger.

The American Shakespeare Center wants to help turn Staunton into a popular tourist destination. Outside of Shakespeare, the place does have a lot to offer: beautifully preserved turn-of-the-century local architecture and a big elegant hotel, the restored 1924 Stonewall Jackson, whose roof-mounted, letter-stacked sign acts as a visual trademark for the downtown area; a local culture of the chic and the cheap, with antique shopping, coffee shops, and a range of dining options; the nearby Blue Ridge Mountains, with all the camping, canoeing, and hiking to be had there. The brochure writes itself. What Staunton doesn't yet have, though, is a large Elizabethan outdoor theater called the Globe.

With a $200,000 grant from the Virginia General Assembly, the American Shakespeare Center has begun scouting sites for a reproduction of Shakespeare's Globe. As Tony Smith, the ASC's new business manager explains, the plan is to turn Staunton into “an international Shakespeare campus.” This is as much a business and marketing goal as a theatrical one. At the end of his very first week as business manager, Smith learned that the money was not there to make payroll. And yet, the organization was, in some weeks, “awash in cash.” A new ethic, departing sharply from casual dysfunction typical of creative nonprofits, was called for, Smith recalls. “I said, as we are on the stage, so must we be performance-driven as an organization.” This began with identifying core competencies, a process that helped Smith realize the educational work of the American Shakespeare Center was, in fact, critical to its financial health. Another realization was that grants from such organizations as NEH and the Virginia Commission on the Arts were essential to the group's well-being.

Smith reports that ASC, after some careful reorganization, has recently completed its first-year ever in the black. With help such as a challenge grant from the NEH, it is even building up its endowment. The group is also busy reaching out to potential sponsors to underwrite construction of the Globe, a project that promises to require financing at least one order of magnitude beyond what it took to build the Blackfriars.

Peter McCurdy, an architect and builder who specializes in timber construction and historical re-creations, has been consulting with the American Shakespeare Center. He should know how to go about building a Globe Theatre since he was the head builder of the London Globe-whose own finances were on shaky ground until it became the beneficiary of a British National Lottery grant.

During an interview , McCurdy makes the case for importing all the timber for this project from England-because it was, after all, English oak that built Shakespeare's Globe. His thoughts help illustrate how managing scruples about historical accuracy can be one of the bigger challenges involved in this kind of work.

Among the team that built the London Globe, McCurdy was the purist. When an American manufacturer donated wood balusters for the long running handrails inside the London Globe, McCurdy talked Sam Wanamaker into refusing this kindness. McCurdy then found a woman who practiced pole-lathing as it was done in Shakespeare's time to make all the balusters-work that ended up being sponsored by the American manufacturer and even partly done on site to get publicity for the Globe and everyone else involved.

Asked about the added cost of such items as genuine English oak, McCurdy says the price would, in fact, be only a small percentage of the whole. But, compared with the Blackfriars, he says, the cost for the whole thing is going to be significant. The Blackfriars was completed for under $4 million, but a reconstruction of the Globe, McCurdy thinks, will cost somewhere in the range of $20 million to $30 million.

To get his first job teaching at James Madison University, Ralph Alan Cohen claimed he could also teach film. Another Shakespeare scholar was about to retire, so it was a good time for him to join the faculty, but movies were not really his subject. And yet they have become central to how he sees the future of theater.

“I believe that for the last hundred and twenty years plays have been trying to be movies. And there's nothing particularly wrong with that, except that the entire theater industry has accepted the movie model” of a complete, letter-perfect representation of reality, an illusion that asks very little of the audience while cloaking it in passive darkness. But movies, for all their inventiveness, cannot do everything. “The only thing a film cannot do is acknowledge and collaborate with the audience.”

For an English professor, Cohen has more than a little of the actor in him. With dramatic flourish he suggests one “headline” after another for this eventual article. But he is always sincere, especially when he says, “My first ideal was to show my students how much fun Shakespeare was. My next ideal was to save Shakespeare for the world by doing it right. My new ideal is that I want to save theater for the world.”